Tuning hammers for tuners are like bats for baseball players: the smallest difference in weight, leverage, or shape is significant. The way the socket fits on the pin (how the diameter taper profile of the socket matches that of the tuning pin) matters greatly. Significant variations in tuning pin sizes and shapes exists between sets. In 1885, Francis Hale introduced the interchangeable tuning pin tip (rather than the previous necessity for changing out the entire tuning lever head) to accommodate this. Length and angle of the head in relation to the shaft is also important.

Tuning hammers are the tool that piano technicians pick up the most often; it is used for tuning, stringing, and in voicing the piano. Because of this, tuners develop a sensitivity to the lever and pin, and can have an awareness of the subtle differences that distinguish one tuning hammer from another.

Early tuning tools were in the form of a “T”, with a striker on one or both ends of the handle, for the purpose of driving the tuning pins into the pinblock (or wrestplank), done in the process of string replacement. This illustration is one of the earliest depictions of a tuning hammer that I have found, drawn by Father Mersenne (L’Harmonie Universelle) in 1637. The instrument is basically a Flemish style harpsichord. Note the hook on the top of the handle, which was for making the braids and loops on the hitch pin end of the string, opposite from the tuning pin. Some “T” shaped pre-1860 tuning tools had this additional hammer function; while modern tuning tools are actually long single levers, the use of the term, tuning hammer, was retained.

Shown below is a tuning hammer for an early fortepiano or harpsichord, which was found in England. The width of the oblong socket is 4 mm.

These tools were typically provided with the instruments at purchase, along with a small supply of strings. There was no standardization of tuning pin size at the time, which is why the socket was tapered. Stringing hooks were often removable, and were used for making the loop and braided end of the single strings on these early keyboard instruments. Thanks to Ed Swenson for the help in identifying this tool.

Late eighteenth century fortepiano, attributed to Dulken and restored by Ed Swenson. Photo from philharmonia.org.

Very small 1840 Broadwood tuning key and tuning pin; later 19th century pin and its appropriate tuning hammer. (photo by “weeT” in the pianoworld.com forum).The National Music Museum at the University of South Dakota has an interesting collection of early tuning hammers, some are similar to this one.

Two small, early hammers, both rosewood, with one striker each.

Two small, early hammers, both rosewood, with one striker each. A Stanley ruler, 6” with 2” extension is in the background. The hammer with a string hook, from the Eastern U.S., has a 5.5 X 7 mm. oblong socket , and the hammer on the right was found in England, and it has a square 5.5 mm. socket. Degree of taper in the sockets of these antique hammers vary, which is another factor for the size of the socket. Some are not tapered.

The old tuning pins were much smaller and had a rectangular or oval top. There was no standardization, and the pin size and shape could vary. Paul Poletti wrote a very good article, “Tuning pins: Modern, antique, or historical”?

Steel hammer with narrow oblong socket, 4.5 X 6 mm. This was a fairly common size in the early 19th century:

Ivory handles and faceted shafts.

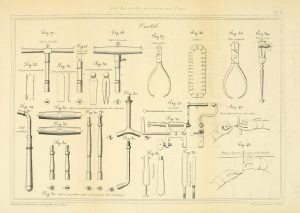

A depiction of equipment for tuning the piano, from L’Art d’accorder soi-meme Son Piano: Une method sure, simple et facile, deduite des principles exacts de acoustique et de l’harmonie, written by Claude Montal, a French piano tuner, and later, manufacturer, in 1836 (1865 edition.) I first saw this illustration in Keynotes: Two Centuries of Piano Design (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), written by Laurence Libin, an exhibition of 70 pianos from Cristofori to the late 19th century; May 29–November 29, 1985.

From left to right:

- Metal tuning hammer oblong socket

- Square socket

- Wood-handled tuning hammer, removable tubes—for oblong and square pins

- Interspersed, three types of mutes, for silencing certain strings during tuning

- Flat-nosed pliers

- Music-wire gauge

- Piano-wire cutters

- Hand vise

- Tuning lever, gooseneck, with stringing hook

- Components for two universal style tuning hammers

- Two tuning forks (diapason) and case (#34 used to draw between the tines to sound the pitch), and looping/braiding machine

- Illustrations in the bottom right show loops and braids being made for the single strings, and then in the lower one the string being wound on the pin, which does not have a string becket and hole (as in modern tuning pins)

Leon Pinet, Paris: Universal tuning hammer. From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner,” Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

Victorian-styled universal tuning hammer, from England. This was carried in J. & J. Goddard’s trade lists for many years.

Otto Bergman, Berlin Universal Tuning Hammer, and action wire bending tool with “T” handle, c. 1927.

Very old French tuning lever, with a beautifully turned rosewood handle, similar in shape to the clef courbe’ shown in the Montal illustration above. This one is 9-3/4” long.

As the 19th century progressed, pianos became larger, heavier, with greater string tension, and some of the tools grew in size as well.

Tuning pins of the 19th century square piano were situated in the back of the case, which means the tuner is required to bend over most of the width of the instrument in order to reach the tuning pins. Long extensions of the tuning hammer helped make this less challenging. Shown below is another universal tuning hammer, which can be used either as a “T” hammer or as a long (16″) tuning lever.

This photo includes both the “T” tube as well as the lever extension for demonstration purposes. Attachments are used separately.

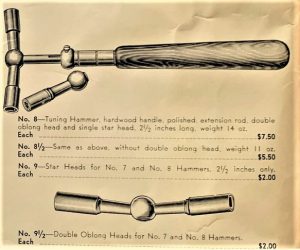

Since the square (and other early pianos) had oblong tuning pins, there are only two tuning positions available. The tuning head with two sockets at 90 degrees made four positions possible. This was called the double oblong head. Even so, the room to work was limited, so some of the tuning would be done with the “T” hammer, which offered little leverage but enabled the tuner to work within a confined area of the piano.

Steinway Square Piano, interior view, with tuning pins near the back of the case. Image from Wikipedia Commons.

Even a saw was included for the tuner. Hammacher Schlemmer: square, oblong, and extractor sockets; Alfred Dolge oblong socket:

19th century extension hammer, with adjustment wheel.

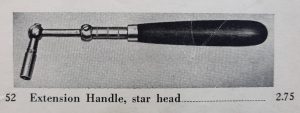

Extendible tuning levers became popular. Even though this feature was originally intended for the square piano, levers with this feature are still commonly available. This is a very light and small lever, which has an extendible shaft almost as long as the handle itself. This example has a brass collar and a round thumbscrew.

Here is an attractive double head extension tuning hammer, not with oblong sockets, but with two square sockets. It predated the introduction of the star socket, so dates from before 1870. The rosewood handle incorporates some sapwood, and the ferrule is bimetal, brass (copper and zinc) and bronze (copper and tin). Most double tuning heads were made with two oblong sockets; a few were made with one square socket and one oblong socket, and some were like this one, two square sockets. The square sockets were designed to give the tuner a leveraged position at every 45 degrees. This hammer has a subtle flat area behind the ferrule, in order to facilitate a quick flipping action of the hammer when changing sockets.

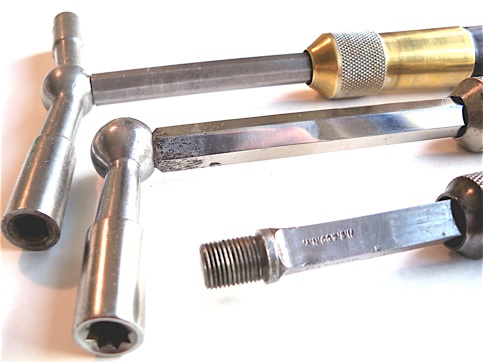

Below are three tuning hammers with set screws and detailed steel ferrules, with bead type patterns similar to those of the old C. H. Lang machine shop in Chicago. The hammer on the top has a tip marked American Felt Co., and the middle hammer, has an extremely short C. H. Lang, Chicago tip. The hammer at the bottom was sold by Tuners’ Supply Co. and Tonk Bros. All three hammers have replacement handles which I turned on a lathe and then bored out (not unlike a woodwind instrument) for the internal tube with the extendible shaft inside. The top two are made with Indian rosewood, and the bottom one is made from brown ebony.

Three extension tuning hammers of a similar type, all with replaced tropical hardwood handles. The top two are rosewood, and the bottom one is brown ebony.

These hammers all had badly cracked original handles. The hammer at the bottom shows the typical diameter of the internal tube within any quality extension lever. With the beaded extension shaft housing exposed, you can see how large the diameter actually is. The degree to which hardwood extension handles are bored out is considerable, and any slight contraction of the wood dimensionally can lead to a cracked handle. This is why ~15% of these handles have a split, anywhere from 5 to 150 years later. And it also makes the extension tuning hammer considerably more difficult to produce than fixed models. –Which I’ve experienced, having fitted a number of new handles to antique examples which had badly split wood.

Beaded extension tuning hammer, from 1940 Hale catalogue, with the same hardware as the hammer at the bottom of the previous photo.

Extension hammer, with exposed beaded extension tube. Tonk Bros. Piano Supply Division Catalogue, 1934. From collection of David Abdalian, RPT.

Some of the hammers below were made in a somewhat ornate, or Victorian style. The shafts of these hammers have a taper, sometimes to a very small diameter, compared to those made in the 20th century. Tuning pin torque (tuning pin tightness in the pinblock) in these 19th century instruments was significantly less than the relatively high torque which is common today, even when these pianos were new. Two hammers, both by the same maker, are shown in the next two photos:

Generally, tuning heads of this period are not interchangeable with those of other makers, and may not be so with various time periods of the same maker’s output. This hammer has fitting numbers, like many tools of this period:

Cut of Piano Tuning Hammers, from The Tuner’s Manual, by Sumner Hill & O. B. Brown, Published in Boston, 1859.

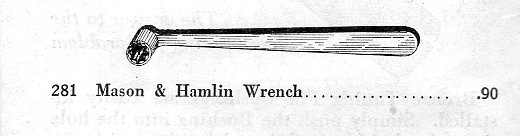

These hammers are very similar to the Victorian hammers photographed above. In the United States c. 1859, the long handled tuning hammers were preferred for tuning. From The Tuner’s Manual, p. 51: “[Tuning hammers] with a long handle [are] generally preferred for tuning, for the reason that it does not tire the wrist and hand, and with it, one can tune more accurately. A good article costs about five dollars ($160 today). The small [“T”] hammer is useful for putting strings on, and driving the wrest pins down when loose. It comes at a much lower price than the other” In England, the “T” hammer would continue to be used predominantly for tuning until the WWI era.

The screw thread that connects the shaft to the head was traditionally straight and not tapered, and often included a friction mating surface of various sizes when the head and shaft are screwed together. This differs from the 1/8″ tapered pipe thread, familiar today, that Hale (Tuners Supply Company, Boston) introduced, c. 1925. Here are three examples—top, octagonal shaft; middle, hexagonal (both same maker); and bottom, square shaped shaft, H. S. and Co.

Top, octagonal shaft; middle, hexagonal (both same maker); and bottom, square shaped shaft, H. S. and Co., N.Y.

Here is a more recent photo of the two unmarked Extension Tuning hammers made by the same maker. I plated the ferrule and thumbscrew of the double barrel hammer in nickel myself (after frustration in hunting for metal platers who are willing to work on personal items). Also, this was a case where the metal could not be separated from the rosewood handle.

The hammer shown at the top was found in northern Maine near the New Brunswick border, in the 1970s. The hammer at the bottom was found around 2010 south of San Diego, close to the border with Baja California.

Chickering pianos were often considered the American piano industry leader until the 1870s, earning the endorsements of many virtuosi of the day, including Franz Liszt.

When Mason & Hamlin in Boston decided to add pianos to their established production of harmoniums in 1883, they introduced a new design of tuning hardware known as the “screw stringer.” In their pianos, the screw stringer design eliminated the pinblock with tuning pins, which has been the established standard since the beginning of stringed keyboard instruments to the present day. It was an attempt to eliminate the tuner’s challenging task of manipulating the tuning pin with its inherent twisting and bending while tuning. The screw stringer did achieve this goal, but did not resolve issues surrounding rendering the string through its termination points: the pressure bar and bridges. This design was partially successful, and it is still possible to tune some of these old screw stringers. Other similar alternative tuning hardware was developed concurrently by Brinsmead (the “Top Tuner” ) in England and, to a very limited extent, Ivers and Pond, also in Boston. Mason & Hamlin continued production of the screw stringer until as late as 1905.

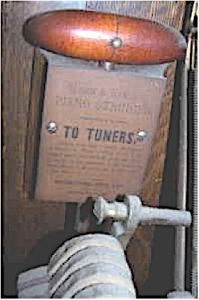

Additional alternative tuning arrangements included the tuning pins fastened directly into the iron piano plate instead of into a wood pinblock, which did not require proprietary tuning tools. Examples of this tuning arrangement include the Wegman “Tuning Pin Fastener” (c. 1890–95, Auburn, NY), Wurlitzer “Uniplate” (c. 1926, North Tonawanda, NY), and the “Beale-Vader Tuning System” (c. 1902, Sydney Australia). Broadwood and Sons, in London, introduced “The Threaded Wrest Pin” c. 1862, where the pin is threaded into the tapped holes of the metal plate above a friction fit into a more traditional wrestplank underneath the plate. Fortunately, these pianos included a warning sign for the tuner about this!

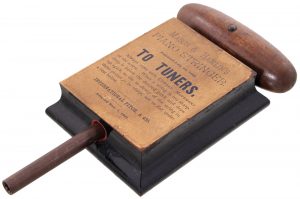

This is a tuning key made by Mason & Hamlin for tuning the screw stringer. It was included inside every new Mason & Hamlin upright piano. It has a star socket to provide eight tuning positions. It also has a long stem so that the turning handle could clear the case, which was helpful for both uprights as well as grands. This tool came from the Hornung estate in 1990:

Mason Hamlin’s Piano Stringer; Patented July 24th, 1883; TO TUNERS, Always tune with UPWARD MOVEMENT of the screw. When a string is too sharp, drop it below the desired pitch and draw it up again, as the tendency of the string in these pianos is to sharp, not to flat, under a test blow. INTERNATIONAL PITCH, A 435 Adopted Nov. 6, 1891.

Mason Hamlin Screw Stringing tool removed from piano by tool collectors. Martin Donnelly Auctions 2023.

It is not OK to remove these hammers from either a serviceable or restorable instrument.

This is the version of the Mason & Hamlin tuning key that was intended for the grand pianos, so that it would not interfere with the stretcher.

Here is a fairly similarly shaped design to the lever above–it was found among the US patents. It has the same basic shape as the preceding tool, with a metal cap, or striker, at the end of the handle, and a long metal sheath at the business end. There is no shaft and the head is directly attached to the heavy ferrule at the front of the handle.

This patent is for a rotating square socket with a clutch feature that allows for many tuning positions more than the four possible with a fixed square socket. A star shaped socket became fairly available no more than ten years after this patent. Nevertheless, designs for a rotating ratchet-like square socket can be seen in the US patents as late as the WWI era.

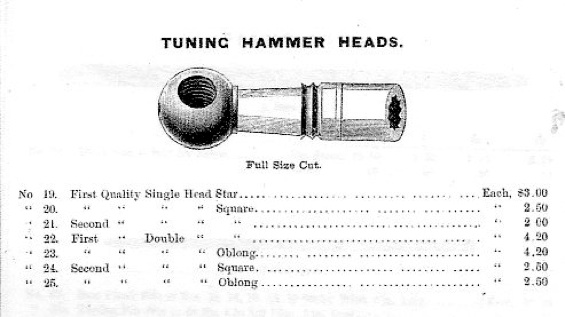

Tuning hammer heads offered in the 1885 Hammacher Schlemmer Piano Supply Catalogue.

This list of tuning hammer heads was offered in the 1885 Hammacher Schlemmer Piano Supply Catalogue. A star tuning socket can also be seen in an early 1885 Hale patent. The star tip made eight tuning positions available with the square tuning pin.

“Stimmhammer,” or German hammer; the beech handle will accept modern Renner type stems. This example, marked “Germany,” was probably made between the 1900s to the ’20s. The rosewood hammer has “STEEL” marked on the shaft and has an oblong socket. It was made by Richard Reynolds of 4 Upper Rathbone Place in London in the 1870s or ’80s. Reynolds was the most prominent maker of specialized piano tools in England in the second half of the 19th century. More can be found on Reynolds here.

From Otto Bergman, Berlin, Tool Catalogue, section for pianomakers, c. 1927: 21 and 22. Tuning hammer, with long and short inserts for changing. 23. Hammer punch. 24. Set screws. 25. Tuning hammer with star socket. 26. Tuning hammer with Adjustable angle for head. 27. Tuning hammer with square socket. 28. Circular floor cutter. 29. Drill bit with perimeter and center cutting.

Curved shafts, known as a “gooseneck shaft” in North America, were used extensively in England, Germany, and France. Hammers with this feature are considered student models at best in North America, but were used in the past for some serious tuning in Europe. The piano industry in Continental Europe and Great Britain primarily utilized various species of beechwood for their piano wrestplanks as well as some other general structural components. Traditionally built wrestplanks made of beech, typically yielded significantly lower tuning pin torque than the hard rock maple sourced from America. American piano makers universally used layers of hard rock maple for their pinblocks, which could potentially yield a tuning pin torque as much as 150 inch pounds. Hard rock maple has a higher performance under compression than beech–from the driven tuning pin. European tuners and stringers did not need the extra leverage and robustly constructed tuning hammers that the Americans required.

“Bluthner pattern” tuning hammer, made by Weygandt und Klein of Stuttgart, Germany. Characteristics include the bend in the shaft directly above the tuning pin tip, and a thickening of the shaft diameter as it enters the handle.

Top to Bottom: J.& J. Goddard, 68 Tottenham Court Road, London (Richard Reynolds); R. Reynolds; H.J. Fletcher, London, German (unmarked); Weygandt und Klein, Stuttgart; German (unmarked); American (unmarked).

This Renner tuning hammer has the short-headed stem, set at more than 20 degrees. Hale had a 20 degree head as well, and it was marked as such. I had a 20 degree Hale head, but sold it off years ago, as the 20 degree angle did not work for me. This particular 20 degree stem belonged to Johannes Warger, a San Francisco based Dutch-American tuner who passed away in 1986.