© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

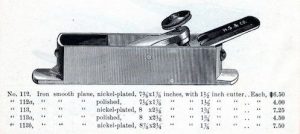

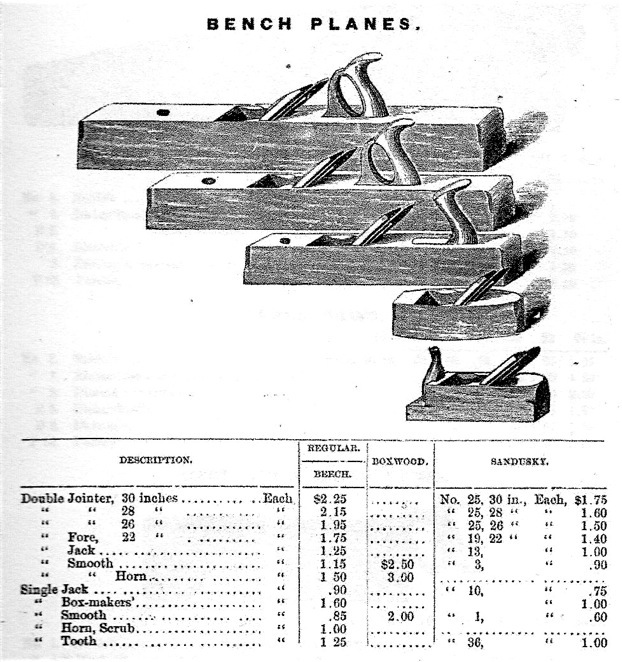

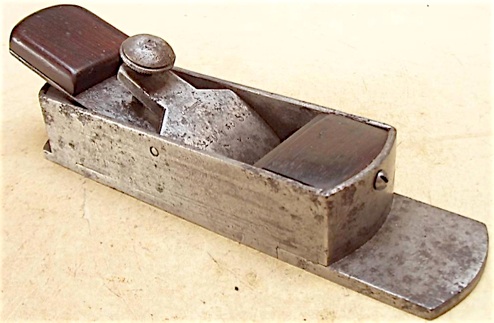

H.S. and Sandusky wooden bench planes, as offered in the Hammacher Schlemmer 1885 pianomakers supply catalogue.

A full range of bench planes were utilized from the beginning of the piano industry until increased mechanization made their use obsolete, or at least, less common. These included smoothing, jack, and jointer planes in transitional, metallic, and wooden forms. Wooden forms were used first, until Leonard Bailey, Stanley, and others introduced their line of metallic bench planes after the Civil War.

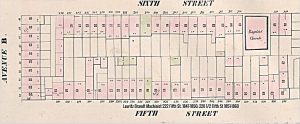

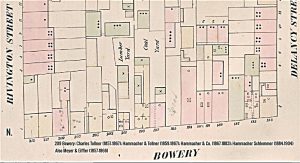

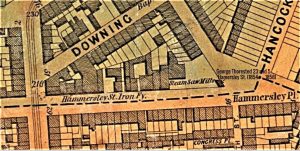

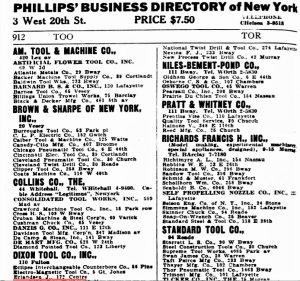

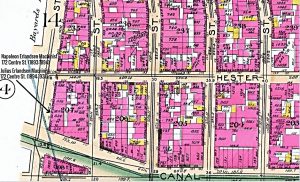

Excerpt from Map of Manhattan, by Dripp, 1867, showing general locations of Brandt, Thorested, Tollner, and Erlandsen.

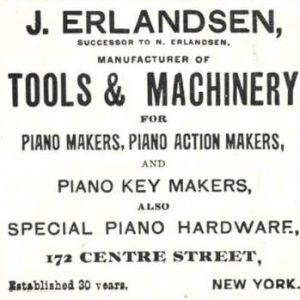

New York City piano makers and their workers, however, had a need for several specialized planes, which were supplied by New York tool makers, such as Napoleon and Julius Erlandsen, Joseph Popping, Lauritz Brandt, and George Thorested. These included box mitres, shoulder, bullnose, and miniature forms, and were known as New York City infill planes. Charles Tollner, a tool dealer on the Bowery between 1848 and 1867, was instrumental as a seller of these tools.

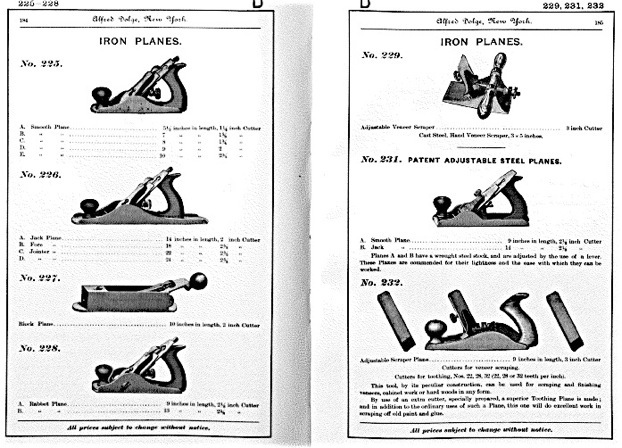

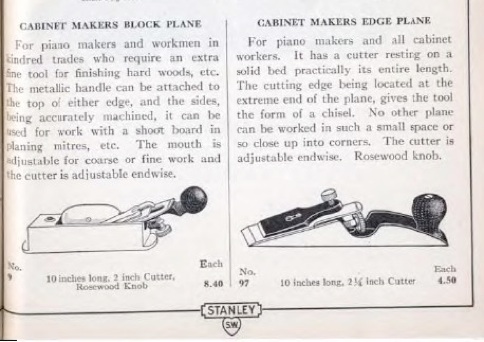

Stanley bench and specialty planes as offered in Alfred Dolge’s 1869-1892 piano supply catalogue. Cabinet maker’s block plane, no. 9 type 2 is shown without “hot dog” side handle.

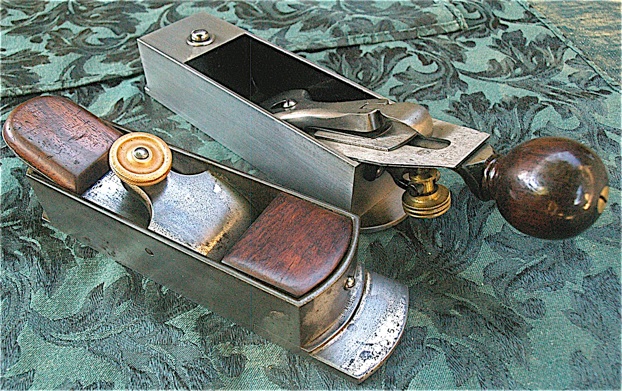

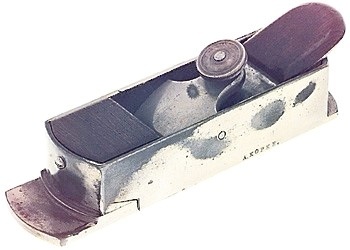

The famous and sought-after Erlandsen mitre plane, is shown below: it helped enable dedicated workers to build many pianos before the days of mass-production panel sanders, thickness planers, and after that for those working for the smaller piano makers. In my opinion there is no other specialized plane that can be characterized as a “piano plane” to the same extent as the Erlandsen mitre. Even recently, surrounded by increased mechanization, this type of plane has remained in use in the Steinway factory to create the crown in the middle of the keybed of their grand pianos. These planes were patterned after the English box mitres, and earlier planes from the European mainland, primarily France, Germany, and Italy, with a low angle blade for cutting end grain and the irregular, difficult grains of some exotic hardwoods. The tall sides of the plane, set square to the sole, enable the tool to be used on its side to shoot mitres and angles, and could also be used with a shooting board. It is actually a very large block plane, and Leonard Bailey/Stanley introduced the #9 (their version of a mitre plane) before the production of their other block planes. These were also sold as “smooth planes,” as in the Hammacher Schlemmer catalog entry shown further down on this page, so there were many uses.

Before this group of New York toolmakers could produce an adequate amount of specialized planes for the piano industry, English mitre, rebate, and other infill planes were imported. But these planes were expensive, especially with the added cost of shipping them to the United States, so sufficient quantities were not available at a reasonable price. Also, the size of English mitre planes at the time averaged ten or eleven inches, somewhat larger than what was sought by the U.S. pianomakers.

A major difference between the Erlandsen box mitre planes and the older English box mitre planes was that the main iron body of the Erlandsen plane was cast in a single piece compared to the English practice, where the sides of the plane were dovetailed to the sole, which was a more expensive and laborious process. Napoleon Erlandsen, who was an expert machinist, was able to maintain quality and save expense by using this efficient approach. The front of the sole was cast in a separate piece, though, which provided the user with an adjustable mouth, as well as making the mouth (aperture for the blade) easier to manufacture. A small mouth was necessary for fine cutting and avoiding grain tear-out in this type of low angle plane. These were simple planes that worked very well, and never incorporated the adjustment mechanisms that Stanley/Bailey used in their planes, but the specialized New York infill planes were often the tools of choice for the piano making workers on the East coast of the United States.

N. Erlandsen mitre plane and Stanley No. 9 cabinet makers block plane (or pianomaker’s mitre plane). The New York/Erlandsen type was introduced first, c. 1840 and 50s, and the the Stanley #9 was developed by Leonard Bailey before he worked for Stanley, in the late 1850s into the 1860s. A side handle for the #9 is not shown here. Both miters are cast iron, and have an adjustable mouth. The sole of the No. 9 is 1/8th of an inch longer than the Erlandsen, which was listed as no. 113B in the 1885 Hammacher Schlemmer catalog shown later on this page. N. Erlandsen signed this plane on the small elevated area of the front toe.

Stanley No. 9 and N. Erlandsen mitre. No. 9 is 9″ long with 2″ iron and Erlandsen (H.S. no. 113B) is 8 7/8″ long with 1 7/8″ iron and nickel-plated body and lever cap. Side handle on no. 9 is machined and iron carries the 1892 patent date . Download version.

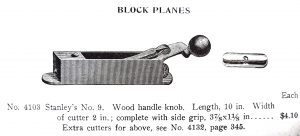

Stanley No. 9 Mitre Plane, in the 1911 American Felt Co. Catalogue, but depicting a much earlier version from the 1880s.

Steinway presently uses a range of Lie Neilsen planes in their factory. This has included the #9 and the #97, bronze versions.

Stanley Catalog, 1934. The #97 chisel plane is shown further down on this page. Number nines were described as 10″ long, but the example above, ~1900, with an 1892 blade, is 9″. After the turn of the century, the sole was shortened; this was probably driven by customer demand as well as to compete more closely with Erlandsen. In the example above. the shorter sole was attained by diminishing the size of the front and rear extensions. No. 97 chisel plane shown further down on this page is 9-1/2″, not 10″.

LAURITZ BRANDT

A talented machinist and planemaker, Lauritz Brandt, innovated and developed the New York style mitre and rebate planes. His planes were distinct from those made by the English makers of the time, including Robert Towell and Stewart Spiers. Brandt mitre planes were immediately distinguishable from English models by having a convex plate at the front of the body, while English mitres had a flat plate. Brandt’s early mitre planes had wedges and bridges, but after 1844, he introduced lever caps and adjustable mouths to many of his mitre planes.

Brandt’s introduction of these planes to the burgeoning New York piano industry of the time, allowed individual piano factory workers as well as piano manufacturers to purchase planes at lower prices when compared to imported English mitre and rebate planes which were used previously. English mitre planes were typically 8″ to 11″ long, with irons ranging from 1 5/8″ to 2 1/4″ wide. Brandt’s mitre planes ranged from 6 1/4″ to 10″ long, with irons between 1 7/16″ to 2″ wide.

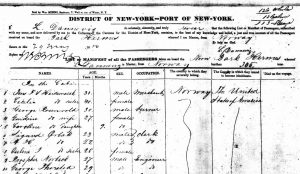

Lauritz Brandt, passenger list. Arrival November 19th, 1836, N.Y., N.Y.; departed from Bremen, Germany; Ship name: Sophie.

Lauritz Brandt was born September 6, 1807, in Svendendorg, Denmark to Anna Dorothea Olsdatter Arnesen (1781-1872) and Cristen Olsen. He was originally named Lars Johansen Olsen, but he changed it to Lauritz Brandt as he reached adulthood. In his early years, he learned blacksmithing from his stepfather, Eric Rasmussen (1787-1868), of Faaborg, Denmark. Lauritz left Faaborg to complete his blacksmithing apprenticeship with two years more training in Copenhagen in around 1827. After 1829, he traveled extensively, working around Sweden, and in the cities of Prague, Vienna, Munich, Cologne, and Berlin. But it was in St. Petersburg, Russia, during the early 1830s, where Lauritz learned precision machining work, at which he truly excelled. Brandt arrived in the U.S. in 1836, 29 years old, hired by inventor David Bruce Jr. No doubt, Lauritz Brandt came to David Bruce with high recommendations.

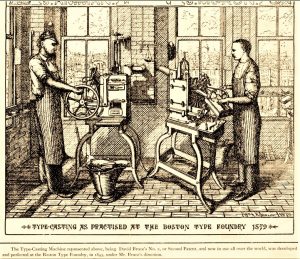

David Bruce wanted Lauritz Brandt to build an example of the his new pivotal Typecasting machine in 1836; typecasting machines made moveable lead type for printers. With Brandt’s mechanical and machining help, David Bruce was able to create a working model of his typecasting machine, that was patented on 17 March, 1838. David Bruce’s invention became the first commercially successful automated pivotal model typecasting machine. David Bruce then sold the 1838 patent for his typecasting machine to his uncle, George Bruce, who was a wealthy industrialist, intent on developing and expanding his type founding business. George Bruce was also a former business partner with David Bruce.

In 1839, Lauritz Brandt married Anna (“Nancy”) Kerrn, (b. 4 May, 1806 in Tyrol, Bavaria) in Misbach, Bavaria. After returning to America, and settling in, Brandt established and ran a machine shop in N.Y. from 1842 to 1880; from 1847 to 1880 on what is now the 600 block of Fifth St. Because Lauritz and Anna had no children, Lauritz likely sought someone to mentor outside of his family. To an undetermined extent, Brandt advised George Thorested, a young, recent immigrant from Norway. When their relationship ended in the late 1850s, he sought another talented individual to take over the piano tool trade.

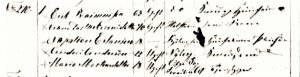

1845 Census of Denmark. Napoleon Erlandsen, 14, foster son of the Blacksmith Eric Rasmussen, 56, and Anna Dorothea Olsdatter Arnesen , 65. Lie Lrese 270, Faaborg.

That person turned out to be Napoleon Erlandsen, who was a foster son in the house of Anna Dorothea Olsdatter Arnesen, and Blacksmith Eric Rasmussen in Faaborg, Denmark (Lauritz Brandt’s mother and stepfather). As an adolescent and young man, Napoleon assisted Eric Rasmussen with his blacksmithing work. Napoleon emigrated from Denmark to New York in 1860, and set up shop alongside Lauritz Brandt in 1863.

On 6 November, 1843, David Bruce patented his second, improved version of his machine, also with the assistance of Lauritz Brandt. George Bruce hired Lauritz Brandt to evaluate the second Bruce Typecasting machine, which, given Brandt’s direct involvement in the development of both versions, seems like a conflict of interest. Nevertheless, Brandt agreed, and provided his opinion on Bruce’s second type-casting machine. Brandt stated that while the second version was good, it did not possess any fundamental advancements over the first version, which George Bruce had already invested in producing. Shortly after this disappointing news, David Bruce sold his patent for the second version to the Boston Type and Stereotype Company.

Two Bruce Typecasting machines, 1843 versions, in use at the Boston Type Foundry in 1879. Image from flickr

Despite Brandt’s opinion, it was the second version that had the most success, which lasted decades:

[David Bruce’s] first version [typecasting machine], which saw only very limited use, was patented in 1838. [David Bruce’s] second version [typecasting machine] of 1843 (with the addition of a nozzle plate in 1845) continued in one form or another in commercial operation until the first years of the 21st century. It ranks as one of the great inventions in technological history.

–David McMillen, circuitousroute.com

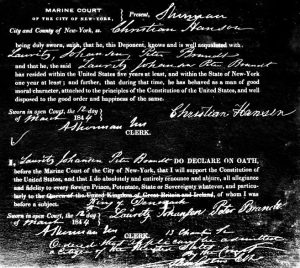

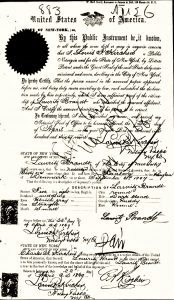

Brandt became a naturalized United States citizen on 12 March, 1844. In preparation to do business in Europe, Brandt subsequently obtained a passport on 3 April, 1844.

Back in the 1840s, the expense of the nascent daguerreotype photographic procedure was prohibitive. Interestingly, physical descriptions continued to be used for passport and conscription documents into the early 20th century, in some cases.

Brandt then went ahead and produced Bruce’s No. 1 patent Typecasting machine in Denmark on his own behalf. Bruce’s U. S. patents did not apply in Europe.

The…adverse inspector, Brandt, [had] made a working model of the Bruce machine, took it to Europe, represented himself as the inventor, and made a moderate fortune.

–-Henry L. Bullen (1857-1938), “The Inland Printer,” April 1922 p. 62

This first (1838) version of Bruce’s pivotal type caster was pirated by Lauritz Brandt and sold in Europe as his own machine. Through the middle of the 20th century you still sometimes saw pivotals in Europe referred to as Brandt machines.

–David McMillen, circuitousroot.com

In “Danske i America,” published 1907 (in Danish), author Peter Sorensen posited that it was Brandt who most likely invented the pivoting typecasting machine, and that it was Bruce who probably received false credit for the invention in America. Sorensen’s writing about Brandt seemed equivocal to me, but there is a relatively small chance that some clarity may have been lost in translation. Nevertheless, I did not find Sorensen’s perspective on the matter of Lauritz Brandt and David Bruce compelling.

Around 1844-1845, Lauritz Brandt went to the typefounder Eduard Haenel in Berlin, Germany, where he first had the Bruce typecasting machine produced. Brandt succeeded in bringing this typecasting machine to market, but in this arrangement, Brandt’s name was not used.

For nearly four centuries, type was cast with hand mold, but in 1838 David Bruce Jr., of New York developed a rudimentary machine on which substantial improvements were soon made in the foundry of Eduard Haenel in Berlin, by the Dane Lauritz Brandt. It was operated by a crank to pump the metal into the matrices, and later a mechanical device for trimming uneven edges was developed.

–Allen Kent “Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science,” vol. 23 pub. 1968

Those “substantial improvements” could have been new innovations by Brandt, or they may have been ‘borrowed’ from David Bruce’s 1843 version two typecasting machine.

Allen Kent (1921-2014) was an information scientist (Library Science) based in Pittsburgh, PA: a generalist. Bullen and McMillen, quoted above, were/are specialists in printing technology. Peter Sorensen’s “Danske i Amerika,” was, in my opinion, a chearleaders’ book on Danish-born men who found success in the United States, under various circumstances.

In 1846, Brandt received a seven-year exclusive right to manufacture the typecasting machine in Denmark. By 1848, the Brandt factory was established in Denmark, ready to produce the Bruce typecasting machine as well as other items. At this point, Lauritz Brandt returned to New York City, where he continued his piano toolmaking business.

I was unable to find Lauritz Brandt in the New York City Directories after 1843-1844 (13 Chambers), and before 1847-1848 (222 Fifth St.). This may have just been a lapse in coverage in the New York Public Library’s particular collection of City Directories, but more likely it was because Brandt was out of the country–in Denmark–setting up his own factory for the production of the Bruce Typecasting machine.

William Perris’ Ward Map of Southern Manhattan shows 222 and 220 1/2 Fifth St. as adjacent to each other. So Brandt moved next door in around 1851. Planes and bow drills made by Brandt were stamped with the 220 1/2 Fifth St. address (1851-1859/60). Later Fifth St. addresses: 417 5th St. from 1860 (1865-1868–shared with Napoleon Erlandsen), and 615 East 5th St. from 1868 to 1881 (1868-1877–also shared with Napoleon Erlandsen), were renumberings rather than actual moves. The 600 block of Fifth St. at present, is still one block east of Avenue B.

In late 1860, Lauritz Brandt moved his home to 136 Second St., and his shop remained at 417 Fifth St. 1862 N.Y.C. Directory.

Napoleon Erlandsen arrived in New York City in 1860; Lauritz and his wife Nancy Kerrn moved to 136 Second St in order to give Napoleon (and his future family) his own living space. The most familiar address for Lauritz Brandt was 220 1/2 5th St. (1851-1860), which was inscribed on the lever caps of many of his planes as well as inside the handles of his bow drills.

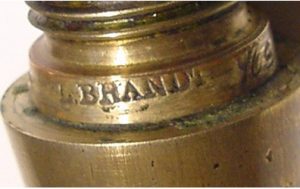

L. Brandt Bow Drill inscription. Photo by Bob Garay.

It is not clear if Brandt actually produced pianomakers’ tools after 1860, as he made a moderate fortune from selling his Denmark factory which produced the Bruce Typecasting machine in 1859.

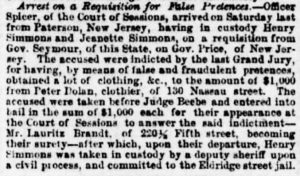

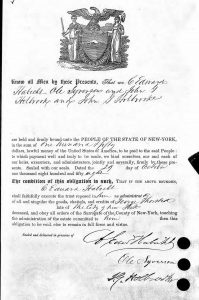

Even before Brandt sold his Denmark typecasting factory in 1859, which made his fortune, he had money. In December, 1854, Lauritz Brandt posted bond for two individuals held in custody.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, Lauritz Brandt made multiple trips to Europe, for business, but also to assist other extended family members.

Actual passport application. April 22, 1869, including his physical description. Issue date April 26th 1869.

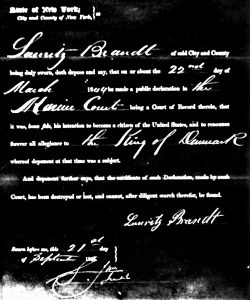

Declaration of allegiance to the United States, and renunciation of allegiance to the King of Denmark. September 21, 1867.

The following year after information was taken for the 1880 U.S. Census, Lauritz Brandt moved back to Denmark, where he spent the last 9 years of his life.

L. Brandt. NYC Directory. 1880. By 1880, Brandt, long independently wealthy, listed his profession as “real estate,” or sometimes “agent” rather than machinist.

Brandt’s burial record: Died June 28th, 1890 in Copenhagen. Buried Sankt Matthæus Sogn, 4 July, 1890.

Lauritz Brandt obituary.In “New York City Makers of Pianomaker’s Planes,” by John G. Wells, from the December 2011 issue of the EAIA Chronicle, Torben Bentsen provided a translation of this obituary:

Brandt, Lars (Lauritz) Johannsen Peter. September 6, 1807-June 28, 1890, Inventor. Born in Svendendorg. Parents: Christian Olsen and Anna Dorothea Olsdatter. The mother later married Blacksmith Eric Rasmussen in Faaborg, with whom Brandt learned the trade of a blacksmith. When in his twenties, he went to Copenhagen, later Sweden and Russia, where in Petrograd, he got lucrative work in precision engineering. In 1831, he traveled to Germany and around 1840 to New York, where he gained employment in David Bruce’s typecasting company. Here he constructed the first practical usable type setting machine. During a multiyear stay in Europe he got his machine marketed in Germany with the company E. Haenel, who did however not mention Brandt’s name. From here and from Denmark the machine was distributed to other countries. In 1848 Brandt founded a factory for the machine and other items. In 1859 he sold the factory to another Dane and lived from his fortune. In 1881 he moved to Copenhagen where he passed away. [He married Anna Kerrn in 1839; she passed away in 1869].

Anna Kerrn became ill during a visit to Copenhagen with Lauritz Brandt in 1869, and was admitted to the Deaconess Foundation, where she died on February 25, 1870.

Brandt Planes

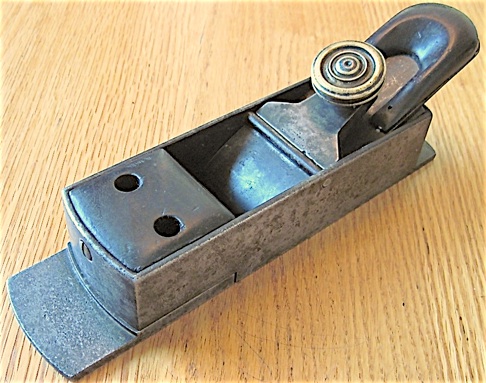

This plane differs from the English mitres by having a convex front piece to to the body box. At just under 10 inches long, its one of the largest NY mitre planes. Some copper based brazing material is barely visible inside the front corners, which leads me to believe that Brandt was relatively new to dovetailing at this point.

Note that Brandt was dovetailing the top or sides of the plane to the sole in a similar manner as the English and Scottish plane makers, such as those made by Norris or Spiers. Brandt was the first to introduce the adjustable mouth to this type of plane, but this a copy of an earlier model with a fixed mouth. In the mid 1840s, Brandt pioneered the use of lever caps for the N.Y. mitre plane. This was around the same time as Stuart Spiers in Ayr, Scotland and Fenn in London began installing lever caps as an option, replacing the bridge and captive wedge in their planes.

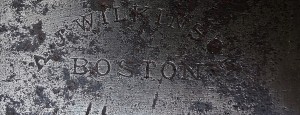

This L. Brandt mitre plane was sold by A. J. Wilkinson of Boston, Massachusetts, a large hardware concern, which was established in 1842.

This dates from the very beginning of A.J. Wilkinson, circa 1842-1844, as the “& Co.” part of the name was not yet added.

A Boston connection indicates that from the beginning of the New York plane makers, Boston piano factory workers were served as well as the New York based workers. Employees within Boston piano factories such as Chickering and Hallet & Davis, prominent in the 1840s, would have had the opportunity to purchase this Brandt mitre plane. If they could afford it. In many cases, the factory itself would purchase the planes. Throughout the 1840s and ’50s, Chickering was the leading maker of pianos in the United States.

L. Brandt mitre plane, inscribed and sold by C. Tollner, with early removable lever cap, of classic Brandt outline. Detailed brass lever cap screw. The heel has two sharp corners, and these corners are dovetailed to a separate rear piece, like the front. This type of Brandt mitre plane dates from the mid 1840s to 1850s.

Here is a detailed map showing 209 Bowery St. drawn by William Perris, which was published in 1852, and I have added a brief chronology of the various proprietors over the years.

Before Charles Tollner moved his warerooms to 209 Bowery. Tollner had his tool and hardware business located at 221 Bowery St,. just north of Rivington St., from 1848 through 1856.

Meyer & Eiffler mitre plane, made by Lauritz Brandt, with adjustable mouth. The lever cap, with indicative sloping shoulders, is held in place with a cross pin above it. Two holes in the front infill give access to the adjustment screws for the separate and moveable front sole. And the pad has an extremely long cutout to give clearance for the lever cap screw after significant blade wear (from eBay).

Brandt mitre with ornate Victorian lever cap. 8 1/4″ long with 1 3/4″ Buck Bros. iron. The plane body is comprised of iron sides dovetailed to the sole. Overall, it’s a very elegant design. Jim Bode tools.

Fancy Brandt lever cap, showing his ornate, differentiated lettering. –Detailed, turned iron lever cap screw. Jim Bode tools.

Brandt mitre plane. Variegated rosewood on front infill. The heel has two sharp bends, and the sides are a continuous piece of iron. This took smithing skills, and probably was done hot, over a form. Photo by Jim Bode.

George Anderson’s mitre plane was also marked by Tollner. Charles Tollner was a tool merchant, whose business later evolved into Hammacher Schlemmer. Tollner was not a maker of tools.

Brandt mitre. Photo from eBay.

Another Brandt mitre, showing a domed-shaped lever cap screw, and a brass plate forming the back portion of the front infill. This brass plate was introduced by Brandt, and adopted by Thorested, with several examples by Erlandsen, in their smaller mitre planes.

Brandt mitre. Brandt’s ornate lettering on the lever cap is partially visible in the photo. This plane was included in “Antique Woodworking Tools” by David Russell, then placed in Stanley international auction held in Leicestershire, U.K., and finally showed up some months later on eBay.

Brandt mitre plane 8 3/4″ long with 1 3/4″ Buck Bros. iron. Domed lever cap screw and ornate lever cap. Adjustable mouth, and dovetailed construction. Formerly from the estate of John G. Wells (1929-2018) a prominent architect from Berkeley, CA.

A few bevel down smoothers in a box mitre body have been found at around 5″, but this plane has a 1 1/2″ bevel up iron set at 20 degrees. One or two ‘toy’ New York finger planes at 3″ have been found as well, but these were one-off examples rather than a genre. This plane has a Brandt angled-shoulder lever cap with screw through pivot rod. And it has an adjustable mouth. It also has a double knurled lever cap screw, similar to Thorested’s. Body is cast iron, and it is well done. While Thorested has generally been credited with introducing cast iron bodies for New York piano planes, rather than dovetailed, its not inconceivable that Brandt may have made some cast planes as well. His years of production were 1842 to 1860, and possibly much later, as he worked and held New York addresses until 1880. Perhaps Brandt made this mitre while sharing his shop with Napoleon Erlandsen in the 1860s.

Lever cap screw shows two different knurling styles on each perimeter ridge, which is indicative of Brandt. This mitre has a cheesehead screw for the strike button, just like the Brandt/Tollner plane shown above.

I have observed at least two other examples of this Brandt cast iron mitre plane. One of them is in the collection of James Claussen.

Brandt rabbet plane with steel cutter seat, c. 1842-1860.

Unmarked iron rabbet plane with sides pinned together over a rosewood infill, consisting of two pieces, one in front, and the other in back, behind and underneath the sloped steel cutter seat. A steel triangular shaped spacer or keeper was placed directly in front of the rosewood wedge, and the top of the steel cutter seat can be seen behind the wedge and iron. The plane has a very thick sole, 1/4″ in fact, and the escapement has the combined rectangle and circle which was used by Brandt, Thorested, and the Erlandsens. This particular plane had a smaller circle, though, which was positioned more on the top corner of the rectangle rather than more out in front of the rectangle, with the bottom of the circle creating a front ‘shelf’ before the actual mouth, as seen on most Erlandsen and Thorested rabbets.

I’ve seen a Brandt rabbet plane with a virtually identical shaped escapement that was photographed in Wells’ December 2011 EAIA article on N.Y. pianomaker’s planes. All of these features indicate that this plane was likely made by Lauritz Brandt, although it can’t be said with 100% certainty. Thorested and Erlandsen also made a limited number of rabbets with sides pinned together over a rosewood infill, but with a slightly different escapement as described above. Some Thorested non-adjustable planes, however, did had a similar escapement like this one. Blade angle on this one is somewhat steeper than is what is typically seen on the New York rabbet planes.

Having a steel cutter seat ensured that the angle for the full length of the iron would stay stable over time, and not be subject to shrinkage of the infill wood. This applied specifically to examples of rabbets where the blade was not resting on—and supported by—the top of the rear wall of the plane. Towell and Spiers rabbets, upon which this plane was partially based, could be susceptible to having the rear part of the cutter seat eventually dry out and shrink to a slightly lower angle than that of the front section. The front portion of the cutter seat would be held to tolerance by the supporting metal components: the sloped upper sole, and the two sides of the the escapement, both behind the mouth.

GEORGE THORESTED

Unmarked Thorested Mitre Plane that sold in the 3 June 2023 Brookline, New Hampshire Auction. Auctioneer’s estimate was $1,000 to $3,000, but the plane sold under the hammer for less than $200! It happens.

George Thorested, who was born 1821 in Norway, emigrated to New York City on the U.S.S. Hermes on May 29, 1850, at the age of 29:

All of Thorested’s pianomakers planes show the strong influence of Lauritz Brandt, especially the earlier ones. Similarities in design features abound generally, but this can also continue down to the smallest details. The fact that they worked within close proximity in Manhattan, as well as both of them having been native to Scandinavia gives strong indication that Brandt mentored the younger Thorested.

Thorested was the first among the New York planemakers to develop a cast iron body for the mitre plane; Thorested’s earlier mitres, however, were made of iron sides dovetailed to a steel or iron sole, in a traditional style similar to that of his elder colleague Lauritz Brandt. With the exception, of course, that these planes had adjustable mouths, in contrast to the English mitres.

It was fairly likely that Thorested made planes at other owner’s machine shops before establishing his own workshop at 23 Hamersley St. in 1854. It was also likely that one of these other shops would have been Brandt’s at 220 1/2 Fifth St. After 1861, Hamersley St. became Houston St., a fairly major thoroughfare running east to west in southern Manhattan.

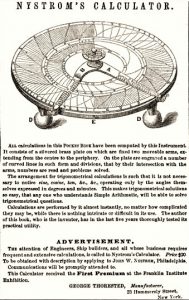

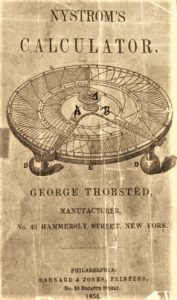

Manual for Nystrom’s Calculator, George Therested, Manufacturer, 23 Hamersley St., New York. Photo by Conrad Shure

This shop was established during Thorested’s working arrangement with John Nystrom, which involved manufacturing the Nystrom calculator. Profits and possible financial backing from making the calculator were the likely source of funding for establishing this workshop, but those profits would have been relatively modest, given that an estimated 100 were made in total. And part of that production was given to William J. Young in Philadelphia. From history-computer.com:

In late 1840s the young Swedish immigrant in USA John William Nystrom, who lived in Philadelphia, invented a calculating device, which was presented and received a First Premium at the Franklin Institute Exhibition in 1849. Later Nystrom received a patent for his calculating machine (US patent №7961, March 4, 1851). In an article of Scientific American the device was hailed as the most important one ever brought before the public. Despite all of the accolades however, it was never widely accepted, and no more than 100 devices were ever produced. This may have been because the cost (there were $10, $15, and $20 models, a huge sum in 1850s), or because the instrument was never well advertised or marketed.

Nystrom’s Calculator, made by George Thorested, 23 Hamersley St. New York. Serial no. 108. Photo from sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk

Nystrom’s Calculator, made by George Thorested, 23 Hamersley St. New York. Serial no. 108. Detail, showing Thorested stamp. Photo from sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk

In 1855, Thorested’s machine shop address changed to 5 Hamersley St., as entered in Trow’s 1855, 1856 and 1857 New York City business directories:

“John” Thorested. Trow’s NYC Directory. 1856. This incorrect entry is the source of the error that George worked with another machinist.

The location of the saw mill on Hamersley was no. 25 in 1852, so the building on the corner would have been 23 Hamersley. Since this was the terminus of Hamersley St., no. 23 Hamersley was likely changed to no. 5 Hamersley St. The south side of Hamersley consisted of even numbers. With an iron foundry on the same block of Hamersley St., it was no wonder that George Thorested found his way to making cast iron planes.

Both mitre and rabbet planes made by Thorested are scarce, because his period of tool production was cut short, and limited to the 1850s. I would estimate that the cast iron mitres and rabbet planes with a double casting, were made after Thorested had his own shop in 1854. The earlier dovetailed mitres and pinned rabbets would have required a number of files and a few other hand tools, which could have easily been carried around to various machine shops during Thorested’s first years in the U.S. –Whereas the necessary time for experimentation and room for casting equipment would have best been done in his own space.

George Thorested 8 3/8″ dovetailed mitre plane, with characteristic upside down “T” shaped lever by Thorested. W. Greaves iron is 1 7/8″ wide.

Nevertheless, George Thorested was still making dovetailed mitre planes as late as 1855, as at least two dovetailed Thorested mitre planes were marked with the 5 Hamersley St. address. It is not outside the realm of possibility that Thorested made some dovetailed planes concurrently alongside some of his cast iron planes. Moreover, in a similar line of reasoning, Lauritz Brandt could have made his small 6 inch cast iron mitre plane during the same time period as his later dovetailed planes, also in the late 1850s. What is clear, however, is that Brandt’s and Thorested’s early dovetailed planes, constructed with iron sides and steel soles, generally preceded their cast iron planes.

George Thorested dovetailed mitre plane, showing striations on the iron sidewalls, and brass plate within the rebate of the rosewood front infill.

Hazard Knowles smooth plane, type 2. sold in Brown 49th auction for $4,068, in October 2016. EAIA website.

Cast iron planes of any kind were uncommon during this 1850s period, which many consider the zenith of wooden planemaking. Hazard Knowles registered the first patent for a cast iron bench plane in 1827, but relatively few Knowles planes and Knowles copies were produced. It wasn’t until the late 1860s that the cast iron plane was produced en masse, by Stanley and their Bailey-designed planes.

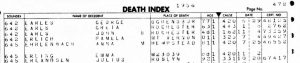

Little has been known about Thorested, and he remains a mysterious figure to the present day. George Thorested was single, and no evidence of extended family in America has been uncovered. I also did not find Thorested in U.S. census records. His last residence was located at 279 East 10th St., in Manhattan. George Thorested died on August 6, 1858 in Manhattan, at the age of 37 from “inflammation of the lungs.” He was interred at Greenwood cemetery in Brooklyn the next day.

George Thorsted’s grave (Thorested) in Green-Wood cemetery, Brooklyn, N.Y. Lot 8100 Grave 737. Thanks to Cara Lowry for her gracious assistance, and to Wallace G. Lane Jr., for taking this photo.

On October 29th, 1858, in New York City, George Thorested’s court probate record was made.

G. Thorested cast iron mitre plane, circa 1854-1858. Photo iluthier.com c. 2005.

Thorested’s lever caps typically had a long neck with parallel sides and shoulders at 90 degrees. An alignment rod for the adjustable sole can barely be seen on the front of the plane body, over the front sole extension.

Thorested (Meyer & Eiffler) mitre plane. Photo from George Anderson on instagram (sqando99). Thanks.

It is unclear what the relationship between Meyer & Eiffler and Charles Tollner was, but there must have been some because they were both at the same address, and they both sold infill planes. The 1866 Directory entry is a late one, and the Brandt and Thorested planes would have been made in the 1850s. Meyer & Eiffler also sold a line of padlocks.

George Thorested cast iron mitre plane, 8″ sole, 2″ wide, 1 9/16″ Greaves iron. The Thorested “T” shaped lever cap has very subtle chamfering (or beveling), which gives a satisfying effect. Note how the sides of the plane body are extra thick: great care was taken with these early castings. Circa 1854-1858.

Thorested mitre plane, with long and narrow body, 1 1/2″ mouth, and moderately chamfered lever cap. Lever cap screw is iron rather than brass. Besides the “T” shaped lever caps, another characteristic of Thorested’s mitres is that the lever cap fulcrum rod is generally placed 2/3rds of the way back from the toe of his planes. On the Erlandsen mitres, the lever cap fulcrum is placed just about at the middle of the plane bodies.

Same Thorested mitre. No rear infill. In a few of these mitres, the iron is supported by two runners, as part of the iron casting. Not visible in this image, however.

Thorested mitre plane. 9 inches long, with a 2 inch Buck Bros. iron. Lever cap screw inscribed “G. Thorested 5 Hamersley St. N.Y.

Thorested’s small mitre is 5/8″ shorter than a Stanley No. 19 block plane, but Thorested’s was discontinued a good 30 years before the No. 19 was introduced in 1888. Besides, the solid feel and accuracy of the Thorested mitre bears little comparison to the Stanley, save that they both have bevel up irons and adjustable mouths. This mitre has excellent fit and finish, and attention to detail, noting the heavily chamfered lever cap, and tight mouth. On the side, you can see the screw-through lever cap cross pin, and if you look closely at the top of the side, there are a couple pin head size casting voids that were filled with copper brazing material by Thorested. With a rounded over shape, like the bowler hat of the mid-19th century, this lever cap screw shows the influence of Lauritz Brandt.

Thorested mitre plane 7 5/8″ long with a 1 5/8″ iron. Lever cap marked “G. Thorested 5 Hamersley St. NY.” From estate of John G. Wells. Photo by Jim Bode.

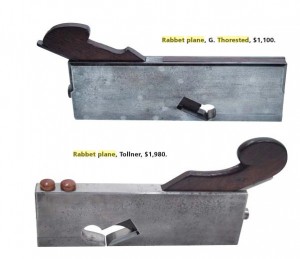

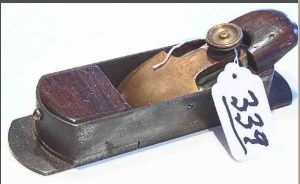

This Thorested rabbet plane was made between 1854 and 1858, and was sold by Meyer & Eiffler, 209 Bowery St. N.Y. Meyer & Eiffler was a small hardware concern which sold a wire gauge, various padlocks, and a limited number of New York pianomakers mitre planes as well. Threaded plugs for adjustment screw holes not shown in this photo. Deeply recessed adjustment screws for adjustable mouth, even though not easily visible, are clocked.

Under probable budget constraints, George Thorested fashioned the iron for this rabbet plane from an old file.

The Thorested/Meyer& Eiffler rabbet plane was made from two cast iron offset body halves which have been pinned together–the right body half holds the sloped cutter seat. A seam between the two body halves can be seen faintly along the top of this plane, about 3/4ths of the way over to the right side. An adjustable throat could be set with two clocked cheese head screws deeply recessed at the bottom of the two holes at the front top of the plane. These holes were threaded, and this plane came with two threaded plugs. Alignment was maintained by two studs on the top of the adjustable sole, which were held in place by two elongated corresponding slots on the bottom of the front portion of the plane. Most of these features point to George Thorested as the maker of this New York pianomakers plane.

Thorested’s rabbet with two cast iron halves led the way towards Erlandsen’s design for a rabbet plane, which was a relatively complex single iron casting, requiring cores.

Thorested plane (c 1851-1858) made of iron stock and steel sole; its pinned together. Tollner plane (Thorested), cast iron in two halves pinned together. Same model as the Meyer & Eiffler rabbet shown above.

Mystery New York Mitre Plane. Thorested?

It’s not entirely clear who made this attractive cast-iron 9-inch New York mitre plane shown below, which displays iron, bronze, and brass in contrast with the rosewood. Here are some collector-oriented details about the niceties of this plane, which I will compare with other N.Y. piano plane makers. Much of the information used here to compare the various mitre planes can be found in this excellent article: “New York City Makers of Pianomakers’ Planes” published in the December 2011 issue of the The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, written by John G. Wells.

- Exquisite machining was done on the brass lever cap screw, with two concentric rings separated by a concave area in the face, a dimple in the middle, and two knurled rings on its outer edge. While not unlike Erlandsen lever cap screws, this one is more detailed.

- The front infill, with a concave moulding in front of the mouth, is made of one piece of solid rosewood, instead of having a lesser wood glued underneath the rosewood and a third convex vertical piece in front of the mouth, as seen on Erlandsen mitre planes.

- Gunmetal (bronze) was used for the lever cap instead of iron, which was typically used by the known N.Y. makers, with some exceptions. Underneath the bronze lever cap there is a clearly delineated 1/8th -inch thickening surrounding the threads of the lever cap screw, but it is not the same as the 3/16-inch inverted cone on the Erlandsen mitres.

- The lever cap, with a long neck and parallel sides, is shaped differently than Erlandsen’s or Thorested’s. But the cross pin for the lever cap is threaded into one side, like Thorested or Brandt’s mitre planes. Since Brandt used dovetailing in the construction of his planes, Brandt can be ruled out, and it doesn’t look anything like the Popping mitres. The W. Butcher 2-inch iron was pretty much the widest offered in the largest N.Y. mitres, and Thorested was known for using W. Butcher irons among others.

- In order to clear the long lever cap neck for the blade as it wears down, a concave area was made on the front of the pad. Cheese-heads machine screws are used for adjusting the front sole piece beneath the infill, as do Thorested”s planes, while Erlandsen’s have round head machine screws.

- On the front sole extension is a 3/32″ step down, the same as in N. Erlandsen’s mitres; Thorested’s step down was only 1/16″.

- On the front end of the body of the plane there is a noticeably more convex curve than what is typically seen on an Erlandsen, but some of Thorested’s mitre planes do have front and rear curves this pronounced, or even more so. Other important details characteristic of Thorested such as a guide pin for the adjustable front sole piece, are missing however.

- This plane could have been made in an upstart N.Y. machine shop, but if that was the case, it was an excellent one. What do you think?

-

Some Erlandsen History

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

Napoleon Erlandsen, 18, in the 1850 Denmark Census. Also Eric Rasmussen, 63, and Anna Dorothea Olsdatter, 70. No 210

Fåborg købstad, Sallinge, Svendborg, Danmark (Denmark)

Napoleon Erlandsen was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in March, 1831 to parents Neils and Mary Erlandsen. Previous to immigrating to New York City, Napoleon was raised as a foster son in the house of Dorothea Olsdatter Arnesen, and Blacksmith Eric Rasmussen in Faaborg, Denmark, the mother and stepfather of machinist Lauritz Brandt. Napoleon learned blacksmithing from Eric Rasmussen as his assistant in the 1840s and 1850s.

Departure manifest of the steamship Teutonia, leaving Hamburg, 29 February, 1860. Occupation: Schlosser (locksmith).

Napoleon listed his departure point as Faaborg, Denmark.

Napoleon Erlandsen, 28, a “Smith,” arrived in New York City Harbor on 19 March, 1860. He was a passenger on the “Teutonia.”

Napoleon Erlandsen moved to New York in 1860, and began making tools for the piano trade around 1863. From 1860 Napoleon lived and worked from 417-419 Fifth St., which was owned by his step-brother Lauritz Brandt. Napoleon remained at Brandt’s Fifth St. property until 1877, and during the period between 1860 and 1867 was trained by Lauritz Brandt in the manufacturing of specialized piano tools. Napoleon married Louisa Aubinger (1841-1928), a first generation German-American, in 1864, and they had two sons: Oscar (1865-1943) who became a noted civil engineer, and Julius (December 5, 1866–October 20, 1956), who accompanied Napoleon in business.

Napoleon Erlandsen, 417 and 419 Fifth St. This was formerly 220 1/2 and 222 Fifth St., properties of Lauritz Brandt. Trow’s 1864 New York City Directory.

Napoleon was a skilled machinist, designer and woodworker, and he developed a tool making business that supplied Hammacher Schlemmer, Alfred Dolge, American Felt Co., C. F. Goepel, and Schley, as well as other piano tool and supply retailers outside the U.S. He developed a full line of tools for tuners, action regulators, case makers, bellymen, and other allied tradesmen.

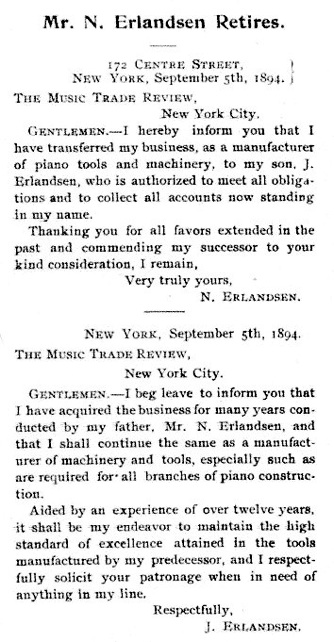

Napoleon Erlandsen handed down the business to his son, Julius. 1894 letter in the “Music Trade Review.”

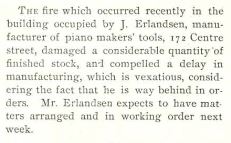

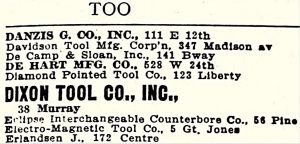

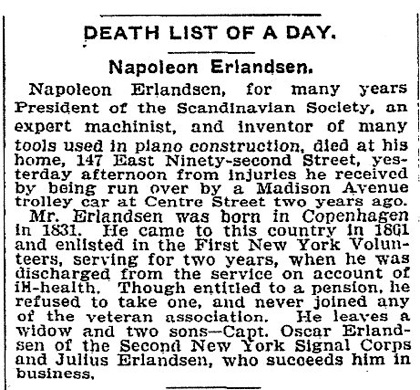

His son, Julius, joined him in the early 1880s, and they worked together until about 1894, when Napoleon retired. Napoleon was severely injured in a streetcar accident and died as a result of his injuries on July 19th, 1900. Julius continued the business until at least 1940, according to the US federal census.

Julius Erlandsen: listing for custom model making. From “Johnston’s Electrical & Street Railway Directory” 1897.

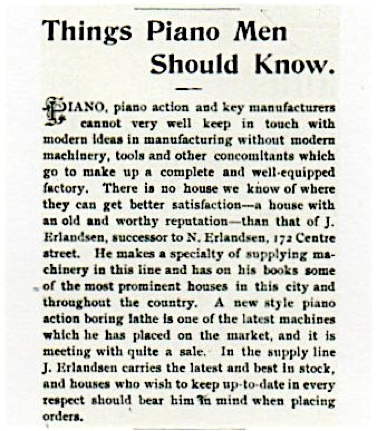

1894 article in the “Music Trade Review.”

This article revealed that Julius Erlandsen was now in control of the company, innovating, and receiving credit for it. It’s just one example of the wide range of products that the Erlandsen machine shop supplied for the piano industry.

172 Centre St., N.Y.C., was the workshop of Julius Erlandsen from 1893 to 1932. From G.W. Bromley 1891 Ward Map of Manhattan.

Julius Erlandsen worked out of his 172 Centre St. shop for 39 years. When Julius left 172 Centre St. in 1932, he was not done; he would continue to work as long as 22 more years.

Erlandsen’s workshop at 172 Centre St. and the building that contained it no longer exists. The current location is used as a car parking lot.

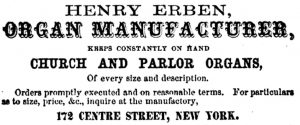

172 Centre St. was the former site of the notable pipe organ maker, Henry Erben (1800-1884). Advertisement from Wilson’s 1858 New York City Directory.

Julius Erlandsen shared space at 172 Centre St. with his brother Oscar Erlandsen, a well known civil engineer in the New York area. From Civil Engineers’ Yearbook for 1896.

Julius Erlandsen was a graduate of Cooper Union, free night school. Julius became an authority in metallurgy.

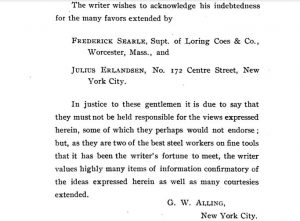

Acknowledgements from “Points for Buyers and Users of Tool Steel,” by George W. Alling. 1903. Julius Erlandsen became a recognized expert in tool steel. I can say from experience that the steel and other metals used generally in Erlandsen products is superior to many others, then and now. Incidentally, Loring Coes held the patent for the monkey wrench.

“…Mr. Erlandsen is an expert judge of and worker in steel, and the fine tempering of the steel used in the production of his tuning hammers is done by himself.” Music Trade Review, 1919.

Julius Erlandsen also held at least 7 patents, which can be seen here. These patents included two for an extension tuning hammer, and others were for machinery, including a rotary cutter, and a wire mattress stretcher.

This U.S. census was to have been completed on 1 June, 1900, so this was a snapshot of the Erlandsen family just weeks before Napoleon died. Their apartment was located at 147 East 92nd St., and Julius’ shop was 172 Centre St.

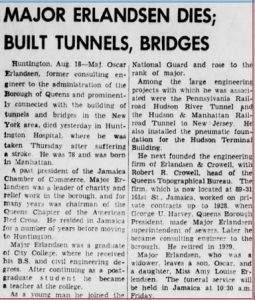

Obituary of Napoleon Erlandsen, d. 19 July, 1900. Oscar Erlandsen, who sometimes served as a witness for Julius’ patents, went on to become a well known civil engineer.

Erlandsen machine shop addresses: 417 5th St (1864-1868–shared with mentor Lauritz Brandt); 615 East 5th St. (1868-1877–also shared with Lauritz Brandt); 87 Elizabeth St (1877-1880); 107 Rivington St. (1880-1893); 172 Center St. (1893-1932); 331 West Broadway (>1933-1940>); 37-58 84th St. Jackson Heights, Long Island City, residence and light work (1929-1953<).

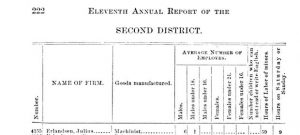

Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of the State of New York …, Issue 11. 1897. Julius Erlandsen had 6 employees counting himself.

The 19th century was not the zenith of the piano industry in the United States. Piano production reached a peak in 1909, with 364,565 new pianos sold that year, according to the National Piano Manufacturers Association. Business continued to be good until 1929. This is why Julius Erlandsen was able to continue as a machinist making piano tools until at least 1940, and possibly as late as 1954, when the Piano Supply Department was divested from Hammacher Schlemmer & Co., N.Y.

The last year of entry for Erlandsen’s 172 Centre St address was 1932. Julius likely was forced to downsize, and move some essential equipment to a smaller space due to the loss of sales during the worst of the Great Depression. Most of Erlandsen’s 1930s tool production would have been for Hammacher Schlemmer. By this time, based on extant Erlandsen tools from the period, I believe that he was primarily producing tuning, voicing, regulating, and stringing tools. Mueller ‘improved, hammer, version 2, is one example of Julius’ late production.

Plane and bow drill production had been greatly diminished if not curtailed during the 1930s. Erlandsen’s bow drill and tuning hammers were included in Goddard’s no. 80 trade list, circa 1938-9. It was the last offering of pianomakers’ bow drills that I have found.

3758 84th St., Jackson Heights, Long Island City, Queens. Some of the apartments are 800 square feet. Photo from Google maps.

Julius Erlandsen and his mother, Louise Aubinger Erlandsen, shared an apartment at 138 East 94th St. in Manhattan since at least 1905. Louise died in 1928, and then Julius moved to 3758 84th St. Jackson Heights, Long Island City, Queens, N.Y.

Julius Erlandsen, in the 1930 U.S. Census, living at 3758 84th St. Jackson Heights, Long Island City, Queens, N.Y.

After leaving 172 Centre Street in 1932, Julius Erlandsen sought out a smaller workshop space, which he found at 331 West Broadway. Diminished sales during the Depression, as well as advancing age likely influenced Julius’ decision to downsize. Erlandsen remained at 331 West Broadway into the 1940s

Julius Erlandsen, Toolmaker, 331 West Broadway, New York City. From 1940 Manhattan Telephone Directory.

Julius Erlandsen was living at 37-58 84th St. in the Queens borough of New York City at the time of the 1940 census. He listed his vocation as a machinist, specifically making piano tools. Julius also declared that he worked a full 40 hour week previous to the census interview, and that he worked a full 52 weeks in 1939.

Based on the limited volume of piano supplies produced during the Great Depression, I’d speculate that Julius was working alone or with one assistant.

Julius Erlandsen was the most prolific of all the New York piano toolmakers, when all of his specialized tools were taken into consideration.

For the 1950 census, Elizabeth Erlandsen, age 40, was listed at 37-58 84th St., Apt. 31. Elizabeth was not home during the initial tally, so this was a follow-up visit. Julius Erlandsen was not counted, but he was likely still living there. I am not sure how Elizabeth was related to Julius, although she was the right age to have been his daughter. Julius was known to be single, and I am not aware that he had any acknowledged children. It was also not outside of the realm of possibility that Julius Erlandsen married Elizabeth, a much younger woman–although, I have not found a marriage document for Julius and Elizabeth. With Elizabeth as head of the household, it does make me wonder if Julius was ill or disabled at this point. When the 1950 census is indexed (2022) perhaps Julius will show up in another location, such as Roslyn, Nassau County, Long Island, N.Y., where he died. In Julius’ obituary, however, 3758 84th St. was still given as his address.

After World War Two, the participation of Hammacher Schlemmer within the piano supply industry was fairly inconsequential. The few H. S. piano tools that were made during the period between 1946 and 1954 consisted of stationary tuning hammers, and a few other basics.

Hammacher Schlemmer stationary tuning hammer, with cross-hatch knurling on shaft. Post War, c. 1946-1954. Crisp machining on a budget tool.

Julius Erlandsen used cross-hatch knurling on some of his earlier tuning hammers.

A handful of small production runs would have been all that was was necessary for Hammacher Schlemmer’s requirements in their Piano Supply Division between 1946 and 1954, something that a reasonably healthy older man, like Julius Erlandsen, could probably accommodate.

Another possible scenario would be that Julius Erlandsen retired earlier, in the 1940s. And when Julius gave notice to Hammacher Schlemmer, they pre-ordered a significant quantity of piano tools, in an effort to forestall having to search for their next specialized machinist.

Cause of death code No. 331 from “International Classification of Diseases,” Revision 6 (1948), was Cerebral Hemorrhage, or stroke. A stroke also caused the death of Julius’ brother, Oscar.

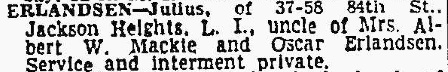

Julius Erlandsen’s obituary in the New York Times on Oct 24, 1956, just a few weeks away from his 90th birthday. He was born on December 5th, 1866.

Oscar Erlandsen Sr. died in 1943; this was his son Oscar Napoleon Erlandsen (1907-1995), an aircraft engineer. Mrs. Albert Mackie was Amy Louise Erlandsen (1901-1996).

An overview of the Erlandsens’ contributions to the piano supply industry are included in “New York Piano Planes, Part II.”

Erlandsen Mitre Planes

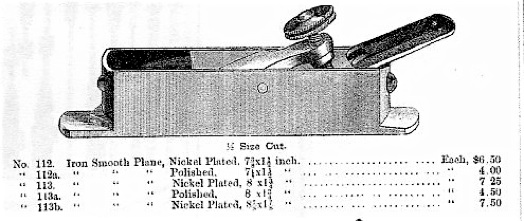

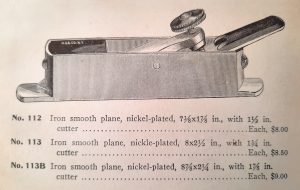

Hammacher Schlemmer’s line of Erlandsen mitre planes in their 1885 piano supply catalogue. Width given is that of the cutters rather than the plane bodies.

Hammacher Schlemmer catalog, January 1,1885: ”Iron smooth plane” showing line of Erlandsen mitre planes. Nickel plating (photo below), a prestige feature, added substantially to the cost, but did not hold up in the places where the hand made contact with the plane body. In this illustration, the pad has a cutout allowing for further blade wear, as on the ‘mystery’ 9-inch mitre shown earlier. It is a variation uncommonly found. The illustration also shows the triangular step-down on the front toe extension instead of the earlier version below this one, where the step-down follows the rounded contour of the plane body. Possibly done as a result of a newer machining process that didn’t require hand touch up, as needed before.

Nickel-plated Erlandsen Mitre. Collectors love the hand print. Plane was listed as sold showing a price of $3,475.00! Those were the days before 2008. Photo from Martin Donnelly c. 2007.

N. Erlandsen mitre plane with very intact nickel plating. Overhang on front infill looks to be rounded over, probably done by the original owner/user. Sold at the April 2016 CRAFTS auction in New Jersey for $2,600.

N. Erlandsen mitre plane, signed, and numbered 357. Sold at the April 21, 2018 MJD auction for $1,800.

Signed Napoleon Erlandsen (twice on rear infill), with the rounded step-down. This would have been H. S. catalog number 113A with 8″ sole, 1 3/4″ iron, and non-plated body. It was found with hardwood sawdust packed between the lower and upper sole.

If the rounded step was discontinued with the introduction of the triangular step by 1884 or earlier, then it would indicate that the bulk of Erlandsen mitre plane production was relatively early, before 1885. Less Erlandsen mitres have been found with the triangular step.

Erlandsen mitre plane, early. Its larger than H.S. no. 113B, with a 2″ Buck Brothers iron. I estimate that it was made c. 1863-1875.

While Napoleon Erlandsen’s mitre planes show more production uniformity than Brandt or Thorested, this example is different, and shows the early development of Erlandsen’s plane making process. The number 152 appears to be roughly acid-etched on the lever cap, possibly a piano factory inventory number. This mitre has definite Erlandsen characteristics: such as the cone-like projection underneath the lever cap, the profile of the body casting, the details of the adjustable mouth, and the lever cap screw. While similar to other lever caps screws made by Erlandsen, save the threaded steel screw column peined flat instead of rounded, it is 1/8″ larger. Front portion with the adjustable sole is longer than typical, and so is the infill, which has the convex moulding in front of the throat. And the pad on the iron is huge, with a large cutout for the neck of the lever cap, which is shortened compared to other Erlandsens.

N. Erlandsen mitre plane, with 2″ iron and 9 1/8″ sole–also larger than 113B (with 1 7/8″ iron and 8 7/8″ sole) in H.S. & Co.’s catalogue offerings. Standard Erlandsen design in appearance, except for the lack of step on toe. Photo from Jim Bode tools.

N. Erlandsen mitre plane, 8″ long, and signed on toe. Rear infill, 1 3/4″ Buck Brothers iron, and front sole piece all marked 6.

Another Erlandsen mitre plane, a later version by Julius. This photo shows the triangular step-down on the front toe extension. Photo iluthier.com c. 2005.

Prices and illustration remained the same as 1885. H. S. & Co.’s 1896 and 1903 prices for Erlandsen mitres were as follows: 112: $6.75; 112A: $3.25; 113: $7.25; 113A: $3.60; 113B: $7.75. Plain steel mitre prices were reduced.

Erlandsen mitre with partially dovetailed, applied sole. Might be an extensive repair, done by a machinist. Slightly different style lever cap. Photo from MJD tools.

Either plane was old inventory, with a later stamp, or the rounded step was not discontinued entirely. Upper side of toe is machined at an angle, and lever cap screw is iron or steel.

Dominic Micalizzi, an early collector of N.Y. piano tools wrote about his early finds of New York piano planes, including planes of Erlandsen, Brandt, and Popping in the “CRAFTS Tool Shed Quarterly,” dated March 1983.

Julius Erlandsen’s Mitre planes, as offered in the Hammacher Schlemmer & Co. N.Y. Catalogue for 1913.