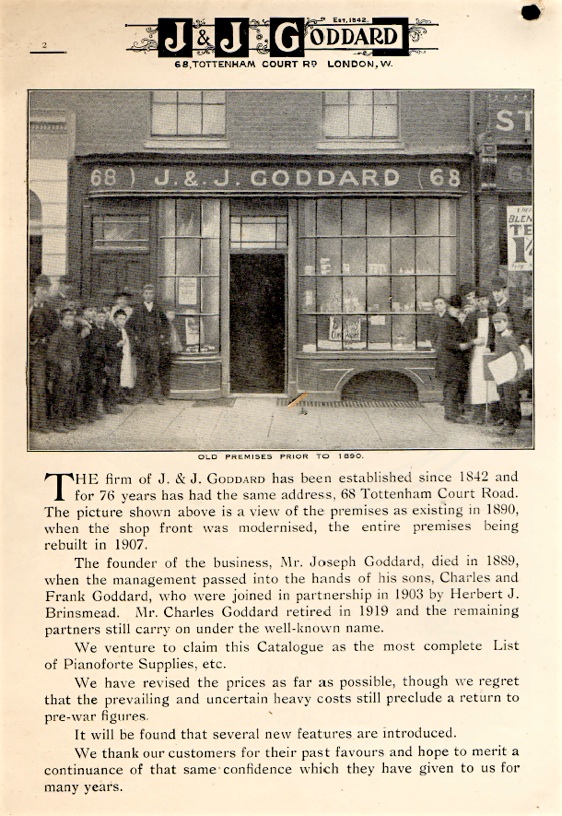

J. & J. Goddard was at 68 Tottenham Court Road until 1968. The last address I could find for them was at 37 Union Street SE1, London, in 1970. Visible from the Goodge Street Station, the “J.& J. Goddard” sign continues to look good, because it was set in tile, not just painted.

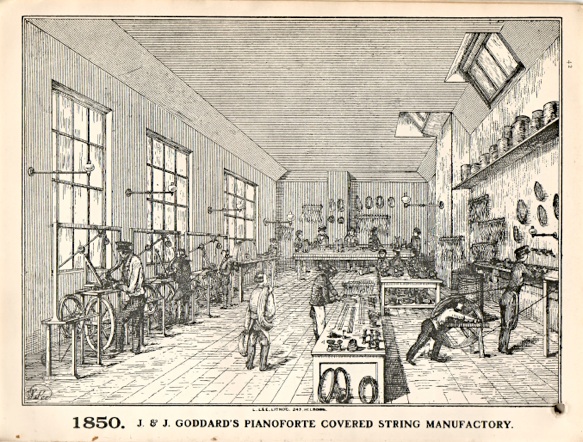

I hope that these children were not involved in child labor.

Much was happening at Goddard’s in 1850.

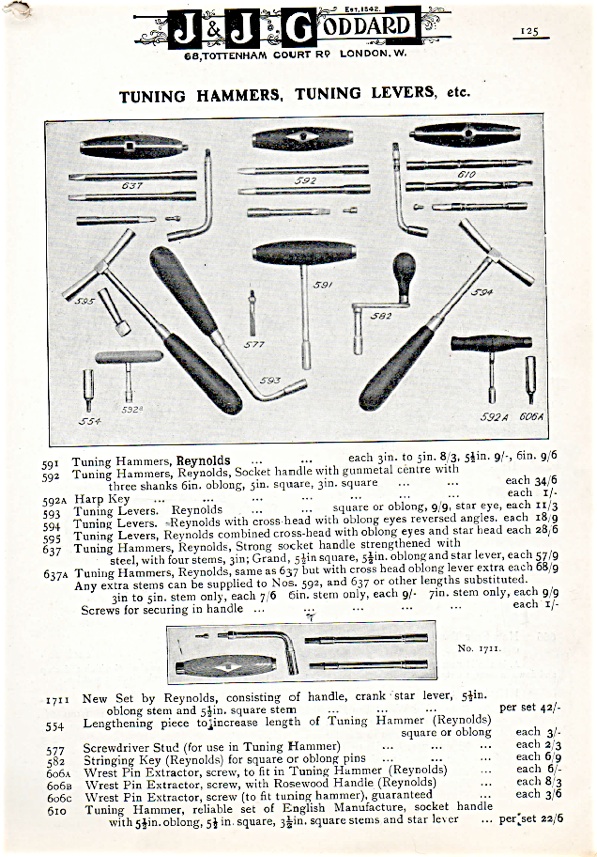

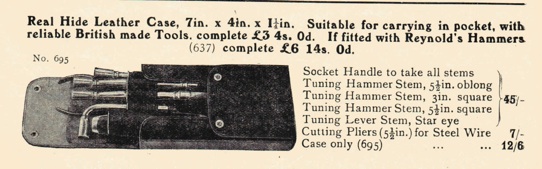

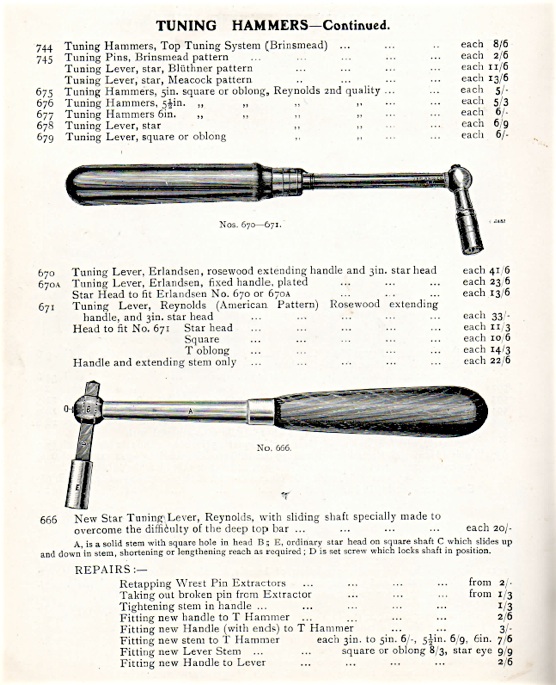

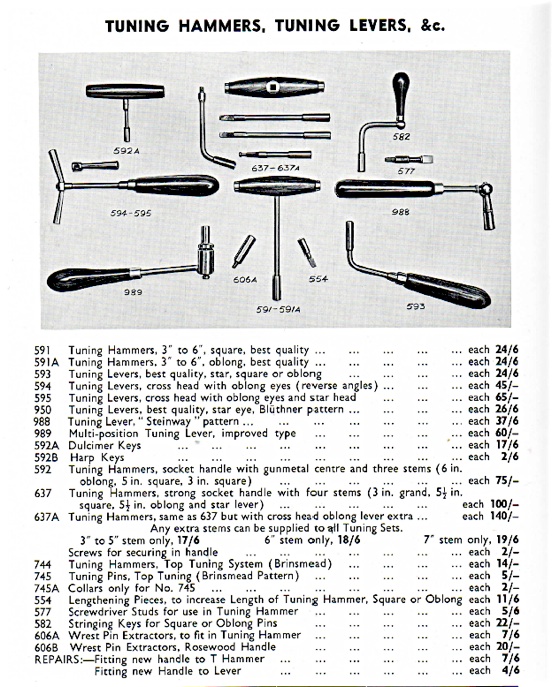

Many tuning hammers were available in Goddard’s 1920 catalogue. “T” hammers and universal tuning hammers were plentiful in 1920, while in North America, “T” hammers were no longer used for tuning, but still used for stringing. They’re still used for stringing today. Reynolds tuning hammers were displayed with an elevated distinction.

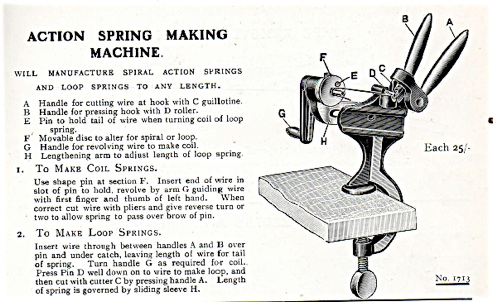

From J. & J. Goddard’s 1920 Catalogue.

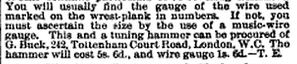

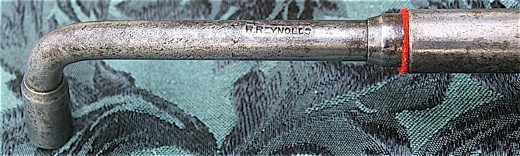

In contrast to George Buck, a competing business at 245 Tottenham Court Road, J. & J. Goddard prominently advertised Richard Reynold’s piano tools. George Buck & Co. had a policy of selling their better tools stamped as their own; if a tool was bought in with an R. REYNOLDS stamp, Buck would either overstamp it with the BUCK stamp or file off the Reynolds stamp first.

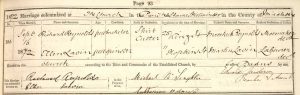

Ellen Lavin married Richard Reynolds at the parish of Saint James in Piccadilly Square, on 16 September, 1871.

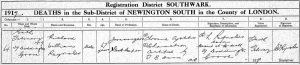

Richard William Reynolds was born on 23 September, 1851 in Westminster, London to Matthew Richard Reynolds and Louisa Elizabeth Harding, and Baptised on 9 May 1856 at All Souls Church, in St. Marylebone. Matthew Reynolds was a shoemaker born in Cornwall, who died in 1852, at the age of 25. On the 16th of September, 1872, Richard married Ellen Lavin (1851-1923) at the parish of Saint James in Piccadilly Square. Early in his working life, Richard Reynolds was a shirt maker.

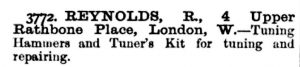

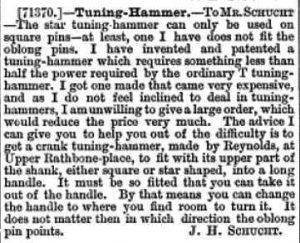

Reynolds was described in British trade publications as “music smiths; [with] Tuning hammers and Tuner’s kits for tuning and repairing.” Richard and his son operated from 4 Upper Rathbone Place, London, circa 1885, and into the 1890s.

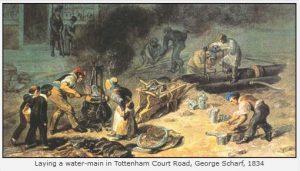

Rathbone Place runs directly parallel to Tottenham Court Road, and Upper Rathbone Street used to be Upper Rathbone Place.

Reference to R. Reynold’s tuning hammers by J. H. Schucht in the “English Mechanic and World of Science,” on 9 May 1890.

By 1890, Richard Reynolds was prominent in the London piano tool making business. In the Victorian era, piano manufacturing was a major industry, with numerous specialists.

In 1891, Richard Reynolds was living in London with his wife Ellen, and six children living at home. Reynolds listed his vocation as “Ironmongers and packer:” Reynold’s 16 year old son, Richard Jr., was an “ironmonger’s assistant.” Products from the Reynolds shop would like likely be packed to deliver locally, such as for Goddard and George Buck over on Tottenham Court Road, as well as be shipped to the distant corners of the British Empire.

At the time of the 1901 census, five children were living at home with Richard Reynolds and his wife, Ellen, and he stated his profession as “ironmongers and stockkeeper. Worker.” Utterly without pretense.

Richard Reynolds rented his house, as shown in the 1910 Land Tax records.

In the Reynolds family entry for the 1911 U.K. Census, 31 year old Helena was a showroom assistant. This job could have been working for her father in the family business.

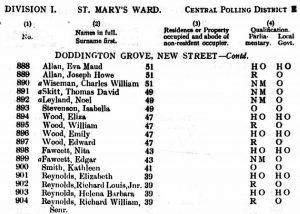

Richard William Reynolds Sr., 68, and his son and successor in business, Richard Louis Reynolds Jr., 44, in the Electoral Register for Doddington Grove, New Street, Southwark, Surrey, in 1919.

Richard Reynolds died at the age of 68; 56 was the average life expectancy of a male in the U.K. circa 1920.

In 1921, as shown in The Music Trade Directory, vol. 32, R. Reynolds was located at L.W. S. R. Arch, 192 Stamford Brook Station, Hammersmith, W. “Tuning hammer and tuner’s kit maker.” This would have been Richard Sr.’s immediate successor, his son, Richard Jr., and subsequently, a family descendant, W. J. Reynolds.

In 1921, as shown in The Music Trade Directory, vol. 32, Richard Louis Reynolds was located at L.W. S. R. Arch, 192 Stamford Brook Station, Hammersmith, W. “Tuning hammer and tuner’s kit maker.”

William J. Reynolds, who lived with his wife Marjorie J. Kite (m. 1930), of 8 Valliere Road, in Hammersmith, drove a motorized lorry as his day job in 1939. England and Wales Register, 1939.

With the worldwide economic Depression in the 1930s, along with the diminishing British Piano industry, making piano tools was not a full time job for William J. Reynolds.

W. J. Reynolds and Sons, “music smiths,” were listed at 192 Arches, Goldhawk Road, Hammersmith in 1940. This was the last entry that I could find for the Reynolds Piano Toolmaking business.

Reynolds tuning lever with square socket, not pictured in Goddard catalogues. All steel, with hollow ground screwdriver inside the handle. Reynolds products shown in these photos strike me as no-nonsense and utilitarian — but very well made.

R. Reynolds all steel tuning hammer with red cloth washer.

Two Reynolds T hammers.

Two R. Reynolds tuning hammers with dealer markings and hard mahogany handles. On the right is a signed R. Reynolds with “J.& J. G,” and on the left is a George Buck hammer with what looks like R. Reynolds filed off.

George Buck was another tool dealer, just up the street at 242 Tottenham Court Road. They catered to many trades, which included a line of piano tools.

Slip gauge for music wire, sold by George Buck, 245 Tottenham Court Rd. London (earlier address), c. 1840-1860.

George Buck’s Tool Warehouse, 242 Tottenham Court Road, post 1880. Left window: “Pianoforte Makers, Coach Makers, and Engineer’s Tools.”

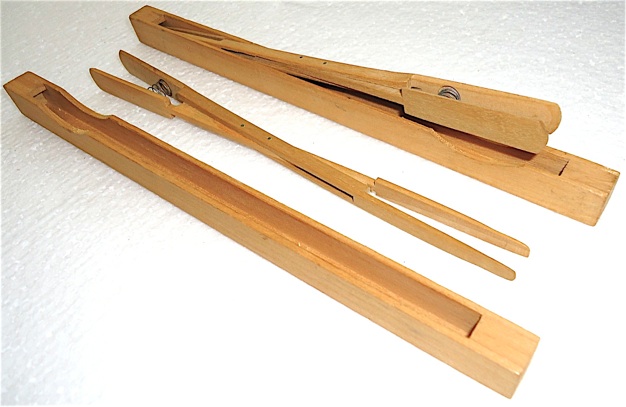

Papp’s tuning wedge, “the fastest muting wedge in the world,” according to Fletcher and Newman Ltd. Papp (of Papp and Son, piano makers , Portsmouth, UK) invented this tweezer-type mute in 1886. It is used for uprights to stop any two strings of a trichord from sounding, utilizing outward pressure from the spring action. This tool does make quick work of muting strings while tuning. The old Papp’s mutes were made from very light wood, until switching to nylon in the 1960s. Thanks to Bill Kibby for this information.

Set of older Reynolds hammers with rosewood handles: oblong socket, and square socket.

J.& J. Goddard tuning lever with walnut handle, made by Reynolds, bottom; R. Reynolds heavy duty lever with Cuban mahogany handle, top.

J. & J. Goddard’s piano tools and supplies warerooms at 68 Tottenham Court Road, and his neighbors in allied trades during the 1860s: George Buck tool seller, 245 Tottenham Court Road; Richard Reynolds, piano ironmonger/toolsmith, 4 Upper Rathbone Place; George Kerr, planemaker, 36 Store St. Bedford Square.

Stock number 610, a “reliable set of English manufacture.” The small illustration in the catalogue hardly does it justice. More ornate than Reynold’s work, this hammer looks like it could have been made a century earlier. Well made, with four carefully fit rosewood infill pieces, it’s hard to see why tuners would pay more for Reynolds hammers. This speaks to Reynold’s reputation, as his equivalent sets were roughly twice as expensive. All of the attachments were marked “STEEL.” This STEEL inscription also appears on a number of English and Scottish infill planes.

Stock number 610, a “reliable set of English manufacture.”

This came as a set, inside a custom-made leather fold-out.

From J. & J. Goddard’s 1920 Catalogue. No. 666 was copied directly from Erlandsen/H.S. Co., N.Y. by Richard Reynolds.

Erlandsen had “more than a national reputation,” as quoted in a 1918 article in the “Music Trades Review.” Erlandsen tools were also featured in the Otto Higel Co. catalogues, out of Toronto, Canada.

If anyone knows what a Meacock pattern tuning hammer is, please enlighten me. I did find a Samuel Meacock (1826-1903), who was an organ builder and piano dealer in Doncaster, Yorkshire.

Samuel Meacock was a pianoforte tuner and seller of Berlin Wool. Yorkshire City Directory, 1857

Goddard’s no. 90 c. 1940s catalogue, with one page of tuning hammers compared to two pages in 1920. Reynolds was not mentioned. No. 988 is the ‘Steinway” pattern lever that was later offered by Fletcher and Newman and by Heckscher Ltd. Reynolds was carried extensively in Goddard’s no. 70 c. 1930s catalogue, as well as Erlandsen tuning hammers. No. 989 was intended, at least partially, for sight impaired tuners.

From J. & J. Goddard’s 1940 Catalogue.

The British piano supply catalogues became progressively shorter over time, sadly reflecting the decline of the piano industry: Goddard no. 50 c. 1920, 204 pages; Goddard no. 70, c. early 1930s, 144 pages; Goddard no. 80, c. late 1930s, 120 pages; Goddard no. 90, c. 1940s, possibly early post war, 84 pages; G. F. Baker, c.1950, 48 pages. Fletcher & Newman’s 1959 and 1976 (centennial) catalogues were larger at 100 and 90 pages respectively, but they consisted of a merger between H. J. Fletcher and Newman & Morgan, which subsequently bought out G. F. Baker and J. S. Tozer.

Three English tuning hammers:

- ‘Steinway pattern’ lever by Fletcher & Newman Ltd., 1970s. The hammer has F. & N. marked on the shaft, and is compatible with Renner, Stuttgart heads. Its handle is a light mahogany (but darker than this photo in my monitor), with a thick hard finish that appears to have been dipped.

- Reynolds, oblong socket, also marked “STEEL.”

- Standard English crank tuning lever, with a square socket, sold by H. J. Fletcher. It’s very short, so it was intended for tuning pianos with less tuning pin torque, with beech wrestplanks, etc. Extra care has been applied in its making, with features such as a large steel pin running through the ferrule, rosewood handle, and steel shaft to prevent any slippage. On the gooseneck shaft, extra steel has been welded to the inside of the bend to add structural integrity.

Three English tuning hammers.

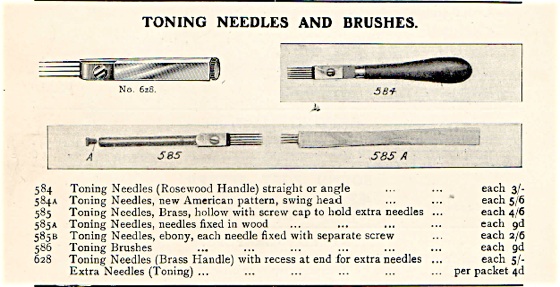

Voicing tools in the 1920 catalogue.

No. 584A was the imported Hale adjustable voicing tool, which was shown in the no. 70 catalogue, circa 1935. A British copy of the Hale adjustable voicing tool was shown in the 1950 G. F. Baker catalogue, and the same tool was shown in the 1976 Fletcher & Newman catalogue—Baker was bought out by them. I have not seen a patent for this type.

Voicing tool No. 584 (foreground) and possibly an earlier version of No. 585 (middle); Curved type in back.

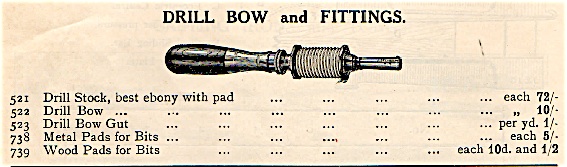

Julius Erlandsen’s Bow drill, as shown in the J. & J. Goddard 1938 Catalogue.

Even though George Buck sold excellent drillstocks up the street at 242 Tottenham Court Road (or perhaps because), Erlandsen’s was still depicted in trade list no. 50, circa 1920. Goddard’s trade list no. 80, circa late 1930s, also included the Erlandsen bow drill. 1938-1939 was the last entry for this tool that I have found:

Two Buck bow drill stocks, found together, one is rosewood, and the other is dark rosewood with the spool possibly ebony. The rosewood drill is shorter and narrower than the darker one, but the shape of the handles suggest that they were made at the same time. Both Buck drills likely were used on the same factory shop floor.

1940s.

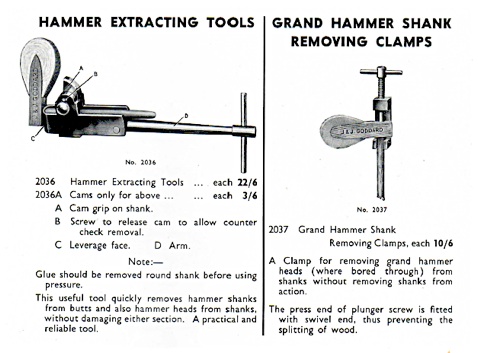

G.F. Baker hammer extractor, with provisional patent, and Baker string coil lifter, based on a screwdriver.

Piano tools made by W. Baker, London. William Baker appeared in the 1881 UK census, listed as a tool maker born c 1837, in London. Not sure if this is an older relative of G. F. Baker.

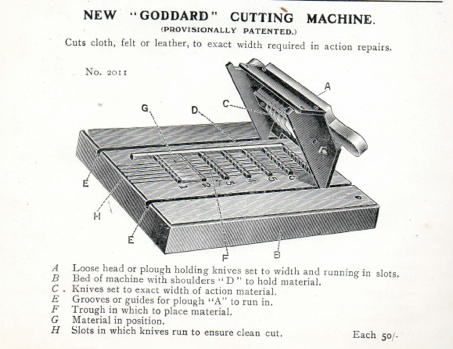

Goddard’s unique cloth, felt, and leather cutting machine. In restoration, these materials are being cut to custom widths constantly. c. 1920.

1940s.

1920.

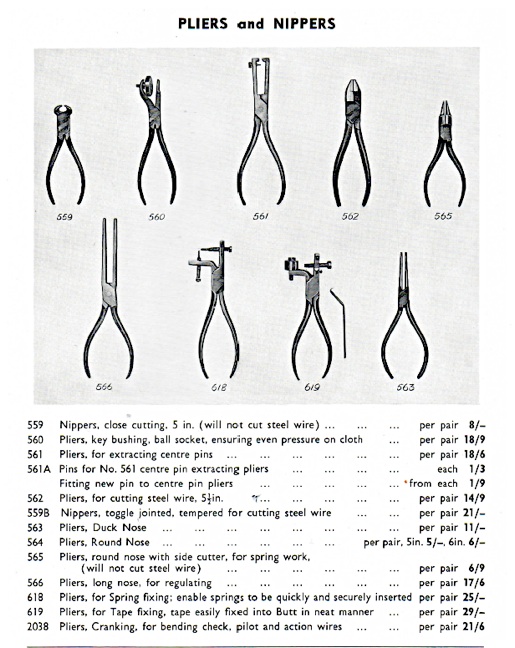

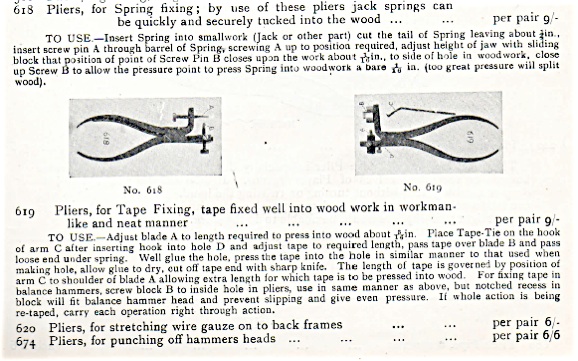

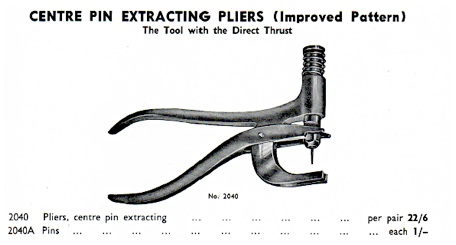

No. 561, based on Wynn Timmons pliers; extracting pin moves on a sweep rather than direct thrust.

No. 560, key easing pliers, ball socket.

Parallel piano pliers–meaning that the jaws are parallel at the width of an average piano action part. Sold by George Buck. Similar to #566 in the Goddard catalogue.

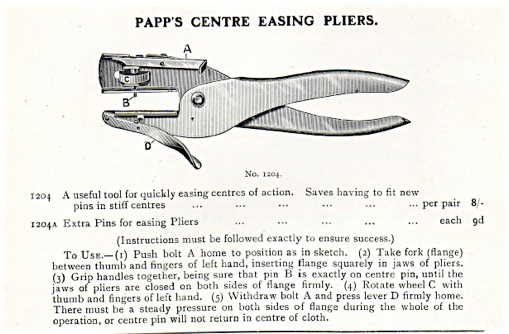

Papp and Son, pianomakers, Portsmouth, U.K. is best known for their tweezer mutes, which were patented in 1886. c. 1920

1940s, direct thrust.

1920.

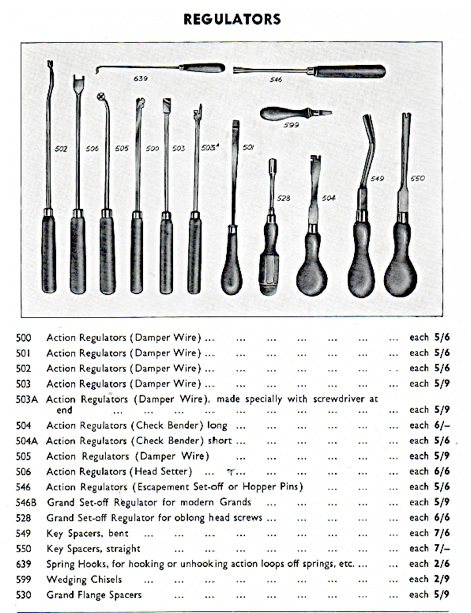

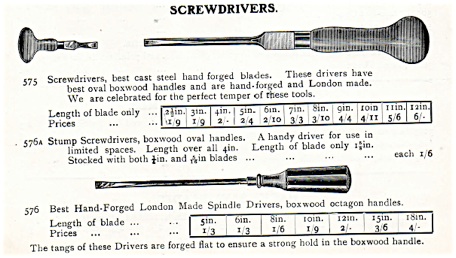

1940s. Three tools on the right are actually based on Sheffield type screwdrivers.

G.F. Baker was a London based piano supply company that sold piano parts, piano tools, and services to the mobile piano tuner, such as key repair and action work. G.F. Baker was in business from 1897 to c 1959, when Fletcher & Newman bought them out.

“G. F. BAKER & CO . , LTD . LEEKE STREET CORNER , KING’S CROSS ROAD ESTABLISHED 1897 LONDON , W.C.1 Phone : TERminus 4302 SUPPLIES OF EVERY DESCRIPTION Pianoforte Tuners ‘ Tools and Tuning Kits Pianoforte Ironmongery Baizes .”

–Music Trades Review, November, 1954, p. 3.

Three English let-off (escapement ) tools. Top beech E.J.H.& D. LTD; middle unmarked, rosewood; “…NHAUS,” boxwood, bottom.

Top to bottom: coil lifter, unmarked; action wire bender, unmarked; bottom three, W. Baker, London, c 1880s.

Goddard 1920 catalogue.

Goddard Bullnose plane, in bronze, with rosewood wedge, and steel face.

Goddard carried a large selection of planes, including a comprehensive range of wooden bench planes and Stanley iron planes. Goddard wrote, “any pattern plane supplied” in their 1920 catalogue. This steel-soled gunmetal bullnose plane has “Goddard London” inscribed on its side, which is partially visible in this photo.

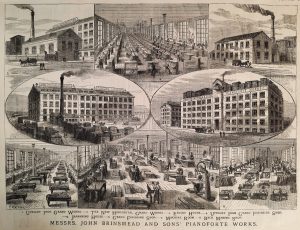

During the height of the Victorian era, the piano industry was booming in London; 6,500 piano workers were recorded throughout the British Empire in the 1881 U.K. Census.