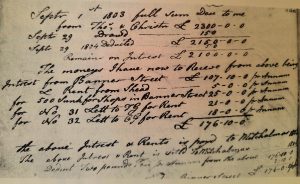

CHRISTOPHER GABRIEL MITRE PLANES

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

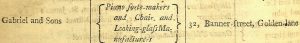

“Gabriel & Sons, Pianoforte makers, chair and looking glass manufacturers.”

-Holden’s London Directory, 1799 .

Early Continental Mitre Planes

Ornamental custom made continental mitre planes were made as early as the 16th century renaissance era and seem to have disappeared in the late 18th century.

These early mitre planes from the European mainland were made as one-off efforts or in small quantity batches. They were typically decorated, sometimes even ornate. This one has a bronze body sweated to a thick iron two-piece sole. It was found in Germany. Typical of the style, it has a complex, turned baluster bridge, and a protruding front hold or tote. The wedge is made of cormier wood, a hardwood almost exclusively found in continental Europe. Sole is proud of the sides, and the front extension has a hang hole, which can be observed on other similar examples.

Curved front totes on these early mitres were probably derived/inspired by the horn at the toe of early Continental wooden bench planes, and still offered on some new German planes. E.C. Emmerich is a prominent German maker of new wooden planes featuring a horn, which makes pulling the plane, as an alternative to pushing, easier.

The cooper who made this plane from oak (same wood that barrels are made of) was most likely an immigrant from Continental Europe. Scribe lines for the mortise are still visible on the cheeks. The tote at the toe of the plane was in the style found in Continental Europe in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Bottom of early European mitre replica by modern maker Wayne Anderson in 2005, showing the through-tenons.

This laborious method of construction was practiced after the earlier method of brazing iron components together in ovens. Note the fine mouth, which is placed near the middle of the sole: its an important feature which affects cutting characteristics, especially with registering the sole of the plane at the edge of the wood for the beginning of a cutting pass.

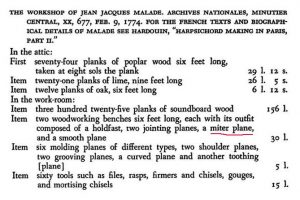

This is a modern translation from French, so the actual word “miter” is Hubbard’s. But its likely an iron or bronze Continental mitre plane similar to those shown above. Showing only the beginning of the full inventory.

Development of the English Mitre Plane in the 18th Century

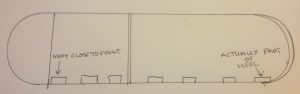

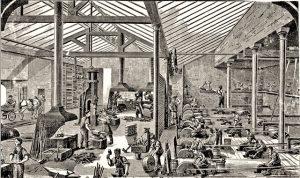

The no-nonsense, clean and simple English mitre plane design first appeared around 1780, or possibly a bit earlier. So there was likely some overlap between the end of ornate European mitres, and the introduction of the English box mitre. Yet stylistically and functionally, a great chasm existed between the two plane designs. Functionally, the blade angle was lowered from 30 degrees to 20 degrees. As a result of this lower blade angle, the mouth was moved forward from close to the middle of the body, to around a third of the length of the sole, as measured from the toe of the plane. The Continental mitre used tenons through the sole to attach the body, and the sole was ‘proud’ of the sidewalls. Early English mitre planes, in contrast, had a sole flush with the body, and the former tenons could then be dovetails on the perimeter of the sole. Forming dovetails on the edge of the edge of the sole was a less laborious operation as compared with drilling out the sole for multiple tenons. English mitres could now be used on their sides for shooting mitre joints. Dovetailing the sole was also a considerably more robust construction method when compared with simply brazing the body to the sole, a common practice in making early European metal planes.

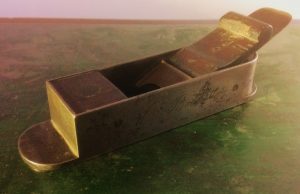

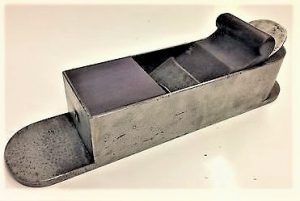

Gabriel mitre plane. Note how the general appearance of this plane is much simpler than the early Continental mitre shown above.

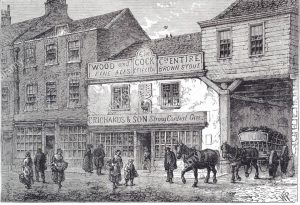

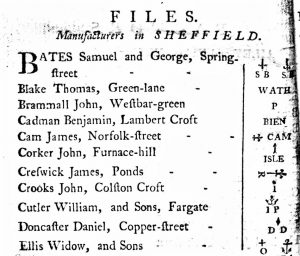

By the 1770s and ’80s, the production capabilities created by the industrial revolution made it possible for a craftsperson to readily purchase strips of iron for the sides of the planes, and obtain tools such as files and chisels for making them–see the Malade shop inventory above. Other tools included metal cutting chisels, hand drills, and metal burnishers. Earlier makers of metal planes on the European continent (before c.1760) did not have these advantages, which is why they are found in even lower quantities. Some of the preceding information was drawn from the 2010 blogs of Joel Moskowitz on mitre planes, and that is appreciated.

“B.H.G.” Mitre plane, dated 1739, and found by Philip Walker in the 1960s. At some later date, it appears like an owner of this plane doubled the sides of this plane, in order to make the sides flush with the sole, for the purpose of using the plane on its side. Photo by Jim Bode.

The late Philip Walker, a founding member of Tools And Trades History Society (U.K.), wrote an article in the 1983 TATHS Journal which described a couple of 18th century mitre planes which he believed to be examples of the earliest English mitre planes. One of the planes was from the Alan Bates collection, and was marked B.H.G. LONDON and 1739. The “B.H.G.” plane subsequently went to the David R. Russell collection and was pictured in his book, Antique Woodworking Tools, as no. 863. The other plane was found in Bristol and purchased by Philip Walker. Both of these planes had aspects linking them to England, although clearly, there appeared to be more of the Continental style in the way of features and layout. One of the more ‘English’ features of these two 18th century mitre planes, was the presence of a front infill, although that could have been added later, in both cases (my observation, not Walker’s). Here is Philip Walker’s summation of the B.H.G. LONDON 1739 mitre plane:

This 1739 B.H.G. plane is understood to have been in the Portsmouth Dockyard workshops for many years, and it has until recently been kept for nasty jobs where the workmen feared damaging their personal tools.[!] To sum up: we appear to have here the earliest known English box-construction plane, the forerunner of all those box-constructed planes which constituted the pride of the nineteenth century joiner/cabinetmakers’ kit. It shares certain characteristics with a considerable series of earlier continental European planes. Whilst the date sequence does not actually prove that the English planes were derived from continental models this plane is one more piece of evidence for the existence of a common European tradition in tool design.

Before Gabriel

I was contacted by an Australian tool collector and researcher, regarding a possible forerunner of the Gabriel type mitre plane. This plane may have been the missing link between the handful of early English mitre planes with both European and English characteristics and the appearance of Gabriel, Sym, and Green mitre planes already with mature features, that would continue basically unchanged until the obsolescence of the form in the mid 20th century.

This 18th century English mitre plane has a front infill and wedge made of Kingwood, and a rear infill made of English oak. The front infill has a slightly ridged surface, indicating collapsing grain, which typically takes more than 200 years to occur, and the rear infill has the remnants of shimming, done to compensate for wood shrinkage over many years. Here is the owner’s description of the timbers used in this plane:

It is my firm belief these [early English Mitre planes] are the precursors to the Gabriel [Mitre] planes…

To begin with the rear (bed) infill is English oak (Quercus Robur) it is very dark, the grain is collapsing and it has the remnant of shimming to surface of bed (all due to age).

The front infill and wedge is a Rosewood (Dalbergia cearensis) it has a specific gravity of 1.2 was highly prised during the reigns of Louis XIV and LOUIS XV was then called Princewood now named Kingwood and has a Violet tinge to the wood. The collapsing grain can be felt (though ever so slightly) on the front infill also testifying to its age.

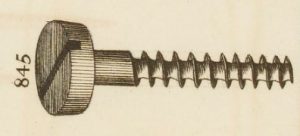

The screws that attach the front and rear infills were cut on an early lathe, the threads (spaces) are different and the diameters are a tad different. Only the rear screw will go into the rear infill and front to front.

This early English mitre plane had a bridge attached to the sidewalls with tenons, and the overall size of the bridge was larger than that found on the later Gabriel mitres. Also, the recess at the front of the bridge was more of a round cutout, as compared to Gabriel bridges, which have a crescent shaped indentation. The James Cam iron, while early, is probably not the original iron. The owner estimated that this mitre plane was made circa 1760.

With the exception of hammer marks on the scroll of the wedge, the kingwood has held up very well, especially the bun. In the front, the finial screw has a slot for driving, and in the rear, just the round shape, for the possible purpose of functioning as a strike button. Also, the base of this screw is slightly concave, in order to conform to the curvature of the plane’s heel, when fully seated.

The collector notified me of a very similar mitre plane that came to auction, that he believes was made by the same planemaker, which has many similar features. This plane had incorrect infills and hardware, which I have tried to resolve using the other early mitre as an example. The large front and rear screw holes did not have a countersink, so the original screws would have either been cheeseheads, or finial screws.

Violet tinge in the Kingwood shows in this photo.

Pre-Gabriel mitre plane, with replaced finial screw and replacement James Cam iron, made after 1800.

Here is another original example of a finial screw on an English mitre plane. This plane was probably made in the middle third of the 19th century. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, March 2024.

Close-up photo of a finial screw on an English mitre plane. Making these finial screw on mitre planes was done, but is unusual to find. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, March 2024.

Another early English mitre plane came to David Stanley auction in February 2024, with some similar features, including the profile of the bridge as well as the tenons attaching the bridge to the sidewalls spaced far apart. The length of the sole is 10 3/8″ and James Cam iron is 1 3/4″ wide. The Cam iron is probably 18th century as it does not have “CAST STEEL” stamped on it. The beechwood infills (appearing to be original), are 1/4″ lower than the top of the sidewalls, and are attached with handcut screws countersunk into the gunmetal sides. The wedge is a replacement, and is made of mahogany that is skillfully stained to match the color of the beech infills. There are two dovetails in front of the mouth, and three behind on each side, and a tenon through the toe as well as through the heel. And the sole is connected at the mouth on either side with an unusual half-lap joint.

From examples such as these, Gabriel mitres emerged with the now familiar box-like form, with wrought iron sides dovetailed to a two piece steel sole. Other English planemakers, contemporaries such as John Green and John Sym, as well as succeeding generations, adopted this general pattern for the mitre plane. Mitre planes were the only generally available metal plane, followed by the rabbet plane by Robert Towell around 1815-1825, then Stewart Spiers and others introduced a range of metallic infill bench planes in the 1840s and 1850s. A notable exception to this would be metal instrument makers planes, which first appeared during the Renaissance era, and made more or less continuously until the present.

I invite any collector who may have another example of this type of plane, with large bridge, and possibly finial screws, to contact me. Thanks.

Mitre Plane Construction

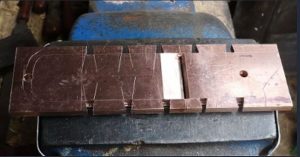

Photo from Bill Carter, UK planemaker. Making a bronze mitre plane. Here the bronze sidewall, with the dovetails cut, is being bent on a form. Then the front plate is attached. It’s essentially the same way that Gabriel would have made his mitre planes.

The layout of the sole, using the sides as template. Body and sole are assembled, then peined together. Photo from Bill Carter.

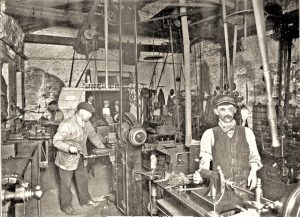

British Piecework System

“Many English toolmakers worked in small shops located in or near their homes. the working and living conditions of this Birmingham nailmaker probably differed little from that of many metalworkers who made tools under the “putting out” system [piecework contributing to multi step product to be finished at a unifying facility]. Ink and wash drawing, ca 1800, by J. Barber (1758-1811). reproduced by permission of Birmingham City Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham, England.” From “Working Wood in Eighteenth Century America,” by Gaynor and Hagerdom, page 7.

Christopher Gabriel very likely used a piecework system like this, especially as his business and production levels grew in later years.

Wooden Mitre Planes and Strike Block Planes

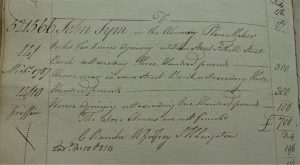

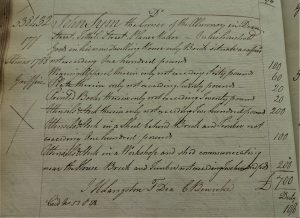

In the 18th century, what we now know as mitre planes were simply called “iron planes.” The 1793 shop inventory for the French harpsichord maker Pascal Taskin made references for “iron planes.” Gabriel’s business record book for 1800 made the first English reference of “mitre planes,” albeit for wooden mitre planes with a mouth closing block or stop.

Wooden mitre plane by Daniel Arthington of Manchester, with boxwood closer or stop. Photo from ebay UK.

Working years for Arthington range from 1808 to 1852, and this mitre was likely an early effort of his. The iron is bevel up with a ~25 degree bed, and the rather thin wood often failed behind the mouth. Nevertheless, wood bodied mitre planes of this type were less costly alternatives to the iron mitre planes.

Gabriel still used the term “iron plane” to notate his iron mitre plane in the 1800 ledger. Subsequent usage of the term mitre plane can be found in the Sheffield tool dealer J. Wilkes catalog of c. 1829:

707. Strait block 2 1/4″ 3 0………………..4 6 (Double)

708. Mitre do. with stop and iron reversed…….9 0

709. Iron do. steel faced…………………………25 0

From “British Planemakers from 1700″ 3rd Edition, by Jane and Mark Rees. Page 111.

Early English mitre planes were expensive.

The “Strait block” (strike block) plane was around 14 inches long and configured with the bevel of the cutting iron facing down with a bed angle ~40 degrees. Historically, the strike block plane had a single iron, but by 1829, a cap iron (chipbreaker), or “double” iron was available for a higher price. Strike block planes, which had parallel sides at 90 degrees, were primarily used for end grain, often with a shooting board. Original examples are extremely elusive, however modern replicas are available.

Original strike block plane, with holes drilled for lead weights. Note the smooth wear on the side of the plane–it was used on its side to shoot mitres. Photo from David Stanley auctions, 2016.

Some Gabriel History

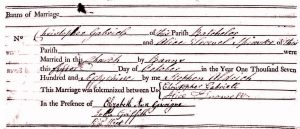

Christopher Gabriel was born in Falmouth, Cornwall on 2 April, 1746, and apprenticed with John Barncoat, Master Carpenter of Falmouth, starting in 1760. Like so many other talented toolmakers after him, Gabriel left the far reaches of England–in Gabriel’s case, Falmouth after 1766–to practice his trade in London.

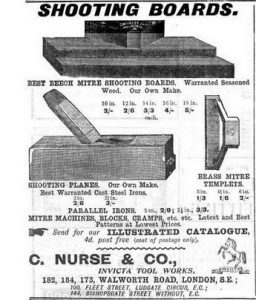

Charles Nurse, late-model strike block plane. From “The Illustrated Weekly Journal for Mechanics, vol. 20, 1900.

Christopher Gabriel started making planes in London before 1770. Not long after setting up his business, Gabriel expanded by offering a full line of tools and additional products. Gabriel soon became one of the most prolific and important toolmakers and dealers of the late 18th century. After his retirement in the late 1790s, Christopher passed away on 23 August, 1809. Thomas and Christopher Jr., his sons, continued making planes as late as 1822. During the 1790s, after Christopher’s sons took over, the firm diversified into making beds and chairs, as well as parts for pianos. As early as 1811, the family became a large wood supplier in London, and they remained in business until well into the 20th century.

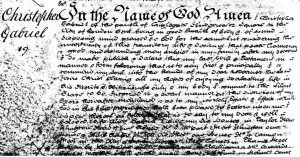

Apprentice indenture, Christopher Gabriel Jr., son of Planemaker Christopher Gabriel, to Henry Carr, 26 April, 1787.

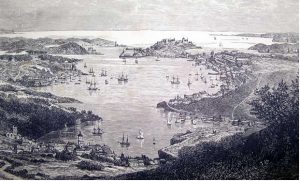

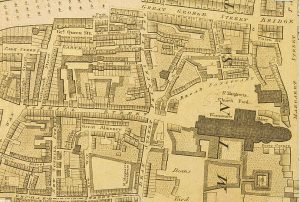

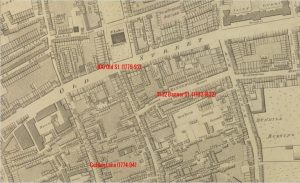

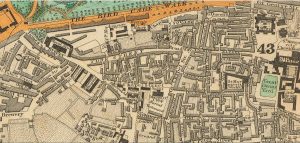

Richard Horwood’s 1792-99 map (partial) showing Old Street and Banner Street in East London, near Shoreditch.

Gabriel worked out of 100 Old Street until ~1793. In that year the business was moved to Numbers 31 and 32 Banner Street.

Gabriel as Pianoforte Makers

“Gabriel & Sons, Pianoforte makers, chair and looking glass manufacturers.” -Holden’s London Directory, 1799 .

In “Christopher Gabriel and the Tool Trade in 18th Century London,” Jane and Mark Rees came to the following conclusion regarding Gabriel’s involvement in piano making:

It has been suggested that the entry as pianoforte makers was an error in the directories but it is probably correct. The firm were unlikely to have made complete pianos, but may have been producing the movements, or more likely, the very numerous parts that made up the movement. The manufacture of piano and harpsichord movements was an early application of mass production techniques in the woodworking trades, It would seem entirely logical the Gabriels would have tried this market alongside the chairmaking and other beechwood items they were making. In this respect, the Gabriel firm is similar to other planemakers who had diversified product ranges based principally on their raw material.

For well researched historical figures like Gabriel, I have chosen not to follow up, or expand on previous work. A thorough review of Christopher Gabriel, his business and contemporaries can be found in Jane and Mark Rees’ fine work on Gabriel cited above.

Mystery of the Mitre Plane

Recently, I encountered this commentary posed by Ian W. in the Australian Woodworking forum regarding the use and application of the mitre plane in England during the 18th and 19th centuries.

8 November 2021:

“Exactly where & how box mitres were deployed in the past has been shrouded by the mists of time. I have never read anything I’d consider reliable on why box mitres were popular for about 200 years then virtually died out. That period (from about the end of the 17th century to the end of the 19th), spans the period of the most intense hand-making of elaborate furniture & house fittings, but doesn’t explain how they were used. A low-angle/Bevel up configuration in a heavy plane is good for shooting end-grain, for sure, & that may have been their main use. In the only old reference I’ve seen with one being used seriously, the bloke was trimming a large mitre using a mitreing vise. I’ve seen Bill Carter demonstrating his own & old mitre planes that he has restored, but I’ve only ever seen him planing long-grain with one, which is not something a low-angle plane with a blade ground to a ‘normal’ bevel angle excels at, it’s too liable to tear out with a heavy cut on cranky woods. In the ‘golden’ age of hand-made furniture, Mahogany was the favoured wood & since it frequently has “rowed” grain, I would think the craftsmen of the day would have much preferred their double-iron bevel-down planes for planing along the grain.”

12 November 2023:

“…how little I knew about mitre planes just a couple of years ago, and how little I’ve managed to learn since. The darned things have intrigued me since I first saw a picture of one at least 40 years ago, but so little has been written about them based on contemporary written records. Most info seems to come from catalogues, which don’t provide much info on how the planes were intended to be used. The sites Ian linked to in the thread are very interesting, the Shepherd site shows a lot of planes, but sheds little light on what they were actually used for, while Joel [Moskowitz’s] suggestions, while based on some sound premises, are still speculative.”

In 2017, Joel Moskowitz posted “The Marquetry Plane Shows up in England 1760-1790.” This was the smoking gun that Joel had been seeking for years. For me, it ends whatever remaining uncertainty I had regarding the process of leveling marquetry being a primary use for the Mitre plane in Continental Europe and England during the 18th century.

Traditional hand tool woodworkers have become accustomed to reading instructive historical books, such as the joinery section of Moxon’s “Mechanick Excercises ,” with running commentary. With the mitre plane, though, we do not have such a clear roadmap regarding its applications and uses. The focus of this website, however, is on providing a multitude of images of all the various tools, and some background on the toolmakers involved, without the primary intention of putting forward a discourse on how the mitre plane was used in England from the 18th century up to the onset of World War I. 18th and 19th century craft workers were not people of letters, if they were literate at all; no one left behind a book on mitre planes, and similar issues apply for any number of specialized tools covered in this website. Mainly, I have stayed away from providing such an historical instruction guide, because I have tried to avoid speculating about an area that has not been clearly documented.

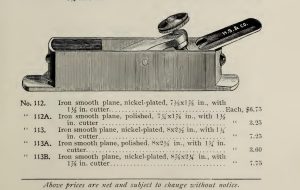

Erlandsen Mitre Planes, classified as “Smooth Planes, in the Hammacher Schlemmer Pianomakers’ Catalogue of 1903.

Having said that, I have tried to provide some information regarding the historical uses of the mitre plane when they have been recorded, mostly from the piano industry within the United States. I disagree that period catalogues did not provide information on how the planes were used: Hammacher Schlemmer, a leading U.S. hardware firm in the United States, classified the range of Erlandsen and Popping mitre planes as “Smooth Planes” in all of their Pianomakers’ Catalogue entries for these tools from 1884 to 1914. And there were multiple editions of the H.S. Catalogues during that time period. The New York mitre planes ranged in size from 5″ to 9 1/2″, and the larger examples were used and documented by Steinway & Sons based in New York and Hamburg, Germany, for creating the crown of the piano keybed from the 1860s until the early 21st century. This would involve smoothing operations along the grain, and also include the end grain of large dowels used beneath the keyframe studs.

Another indication of the deployment of mitre planes in catalogues–through deduction– came in the Joseph Buck, London Tool Catalogue (section for Pianomakers) in 1912. Here we have a full line of Norris mitre planes, from 5″ to 10″, several choices of Thumb planes, and Panel planes. Smooth planes were omitted, which implies to me, that the mitre planes were used at least, for some smoothing. I think that the piano industry considered the mitre plane in a similar way to how we regard block planes in modern times: for end grain, as smoothers, and to be picked up for a range of various tasks, Indeed, the New York mitre planes were slightly smaller than the English ones, and predated the entry of block planes in the early 1870s by several decades. Once block planes dominated the market, the demand for the smaller mitre plane decreased. In examining a number of Popping Shoulder planes over the years, I have noticed a great deal of wear on them–especially the larger ones. Low angle bevel up shoulder planes were used in the piano industry for far more than fine tuning joinery; they were used for a myriad of tasks, as evidenced by all the blown out wedges and damaged mouths.

Also in Hammacher Schlemmer catalogues, the mitre plane was documented for planing ivory for piano keyboards. Mitre planes were sold in the 1926 Feron et Cie of Paris, France Pianomakers’ Catalogue for the specifically designated purpose of planing ivory.

In the organ building business, mitre planes were used for planing spotted metal, a lead and tin alloy used in fabricating organ pipes. Peter McBride attended the close out sale of Fincham Organ Builders, and there he acquired a number of Fincham’s tools, including mitre planes.

Johann Reiter, a famous luthier in Mittenwald, Germany, owned at least three 17th and 18th century Continental (German) mitre planes, and these were photographed in several photographs of his workshop, ranging from 1910 to 1940, and his mitre planes were the largest planes depicted in these photographs. I will refrain from speculating as to precisely how Reiter actually used his mitre planes.

Within my website, I have a page on Spiers, and in that, there is a section titled “Experts Weigh In On the Useablity of the Improved Mitre Plane.” Here, Joel Moscowitz, Chris Schwartz, Karl Holtey, and George Anderson are all quoted regarding the applications of the mitre plane. Their commentaries have been published for some time, and they said it better than I could have.

More on the Mitre Plane

The mitre plane, as it entered the marketplace around 1780, had arrived in its mature form, as created by Christopher Gabriel, John Sym, and John Green. Overall proportions, construction, and features of the mitre plane remained remarkably stable throughout its production period, which finally ended in obsolescence with the onset of World War One. Despite that general obsolescence, old-fashioned piano makers such as Steinway used the mitre plane for specialized tasks, like crowning the keybed, into the early 21st century. Crowning the keybed required a large mitre plane, with at least a 2 inch iron, in order to meet production requirements. “…A miter plane is a design rendered obsolete by mechanization early in this century.” –Maurice Fraser Fine Woodworking 1993

From Gabriel’s early years, a full range of woodworking tools were supplied, but wooden planes always remained his core business. Mitre planes were not stocked in anything but small numbers, and while relatively new and innovative in the English box mitre format, they were not a primary focus of the Gabriel enterprise.

Gabriel’s Mitre Planes: The Serial Numbers

In “Christopher Gabriel and the Tool Trade in 18th Century London,” by Jane and Mark Rees , Rees examined 6 mitre planes:

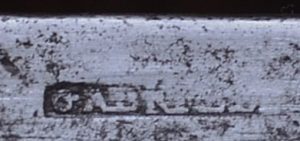

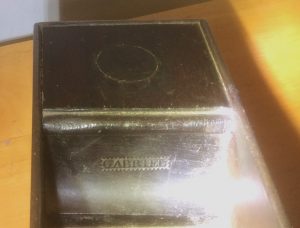

Perhaps the most interesting feature of these planes is that five of the six are marked with what appear to be serial numbers – 415, 492, 700, 701, and 720. This feature has not been noted on the mitre planes made by other contemporary makers such as John Sym of Westminster (1753-1803), and the Ponders, the Gabriels’ successors in the plane-making business.

A Gabriel mitre plane with 309 stamped on the bridge, was featured in a blog by Joel Moskowitz. Moskowitz estimated that there are around a dozen Gabriel mitre planes remaining extant, and that based upon the low volume of mitre components in Gabriel inventory records, mitre plane production was quite limited. I believe that there are more than a dozen, especially when one adds in all of the unmarked mitres having Gabriel characteristics.

After a few more years of observing Gabriel mitre planes, I have arrived at a new tally of 14 stamped and numbered examples. Of course the number of examples are inadequate, but this is what’s available. Numbers span a total of 500 (which doesn’t mean that 500 were made), ranging from the lowest at 220 and the highest at 720. The numbers are: 220, 239, 270, 309, 337, 370, 372, 391, 415, 492, 530, 700, 701, and 720. Gabriel nos. 220, 270, 391, and 700 are available to me for direct study, while nos. 239, 309, 370, 372, 492, 530, and 701 I have observed through multiple photographs.

The infill woods used are beech, mahogany, rosewood, ebony, and walnut. There is a general pattern of wood chosen relative to the sequence of numbers: beech tended to be used early on, with rosewood, mahogany, and walnut used somewhat later, in general. Exceptions exist–nos. 220 and 239 have rosewood infill and appear original; no. 270 has walnut infill. Planemaker Bill Carter reported observing a Gabriel mitre plane with original boxwood infill around 2002. Four of the low numbered, or early planes have infills secured with countersunk flat screws through the sidewalls, with a large cheesehead screw at the heel: 220, 239, 270, and 372, while the remainder are screwed in at the front and back. Nos. 220, 239, 270, and 391 have exactly the same shaped front infill, with identical mouldings at the back. Gabriel nos. 309 and 372 both have a plain beechwood front infill, with no moulding at the back.

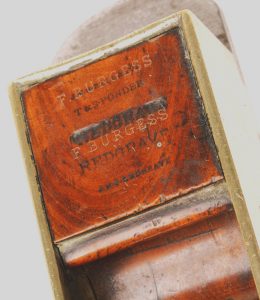

The higher numbered, or late planes, 700, 701, and a similar unmarked example have thick bridges ~3/16″ with a bevel along the crescent recess at the front. 700 and 701 also have a reeded front infill attached with a cheesehead screw through the front plate. The unmarked example also has a reeded front infill and cheesehead screw. All of the other earlier examples have thinner bridges, closer to 1/8″ thick, without the bevel along the curved front edge. No. 220 has a weak GABRIEL stamp on the bridge, with the numbers etched instead of stamped. The next three numbers, 239, 270 and 309, have GABRIEL stamped on the rear of the front infill. Metal (hardness) used for tool stamps would have advanced during Gabriel’s metal plane production (1780-1822) which may explain the weak stamp on #220, and the stamps on the wooden front infill for numbers 239, 270 and 309. Subsequent Gabriel mitres had strong GABRIEL stamps into the iron bridge, which would suggest utilization of a harder steel for the name-stamping punch.

So there is some limited indication that Gabriel mitre build details are linked in clusters with the ascending numbers. That would be consistent with production in batches over the passage of time.

Here is a list of early features in Gabriel mitre planes:

- GABRIEL embossed stamp into back side of front infill (270, 239, 309; except 220, weak stamp into bridge).

- Beech primarily used as infill wood (309, 372, 492, 530; except 220, 239 with rosewood infill).

- Bridge 1/8″ thick (220, 239, 270, 309, 370, 372, 391, 492).

- Front infill top surface 1 3/4″ to 2″ long (220, 239, 270, 309, 372, 492, 530).

- Infills screwed in from the sidewalls (220, 239, 270, 372).

- Bridges attached through cheeks with 4 rectangular tenons (220, 239, 270, 309, 370, 372, 391, 492, 530).

Here is a list of later Gabriel mitre plane features:

- Infills screwed into place (309, 370, 372–screwed and pinned, 391, 415, 492, 530, 700, 701).

- Cheesehead screw attaching front infill (700, 701, 1 unnumbered example).

- Use of rosewood, mahogany, and walnut for infill wood. (700, 701, several unnumbered examples).

- Bridge 3/16″ thick, with bevel on crescent-shaped cutout. (530, 700, 701, several unmarked examples).

- Front infill top 3/4″ to 1 1/8″ long, with long trailing exposed moulding at ~45 degrees. (700, 701, unnumbered examples).

- Bridges attached through cheeks with 4 cylindrical pins (700, 701, several unnumbered examples)

Some foundational build characteristics consistent throughout:

- Thin 5/32″ wrought iron sides (gunmetal sidewalls thicker) dovetailed to a thick 1/4″ blister steel sole.

- Front and rear soles dovetailed together at the mouth.

- Horseshoe bend in the sidewalls at the heel.

- Very rounded front flange, sometimes with extra long extension.

- Cheesehead screw into heel to secure infill (most examples).

Dovetailing:

- No. 220: 3 dovetails in front of throat, 5 dovetails in back.

- No. 239: 3 dovetails in front of throat, 4 dovetails in back.

- No. 270: 3 dovetails in front of throat, 5 dovetails in back.

- No. 309: 3 dovetails in front of throat, unknown in back.

- No. 370: 3 dovetails in front of throat, 4 dovetails in back.

- No. 372: 3 dovetails in front of throat, 4 dovetails in back.

- No. 391: 3 dovetails in front of throat, 4 dovetails in back.

- No. 492: 3 dovetails in front of throat, 5 dovetails in back.

- No. 530: 2 dovetails in front of throat, 5 dovetails in back

- No. 700: 2 dovetails in front of throat, 3 dovetails in back.

- No. 701: 2 dovetails in front of throat, 3 dovetails in back.

- Gabriel (unmarked, with reeded infill like no. 700, 701) 2 dovetails in front, 3 dovetails in back.

- Gabriel (marked, no number, with ebony infill) 2 dovetails in front, 3 dovetails in back.

- Gabriel (marked, no number, with rosewood infill) 2 dovetails in front, 3 dovetails in back.

- Gabriel (unmarked, with rosewood infill) 2 dovetails in front, 3 dovetails in back.

- Gabriel (unmarked, 8″ gunmetal with mahogany infill) 2 dovetails in front, 3 dovetails in back.

Gabriel No. 220

Gabriel mitre no. 220 has the earliest production number, and early features, with the exceptions of the use of rosewood for the infill and wedge, and proprietary stamps into the metal rather than wood. Joel Moskowitz, owner of Tools for Working Wood, woodworker, and antique tool collector, had the following insight into no. 220, plausibly informed by his own experience as a merchant:

My own idea about the numbers is that when Gabriel was making these planes they were rare and expensive – and like expensive things serializing them makes some sense. It’s also reasonable to assume that as expensive items (…he had parts in his inventory but no completed planes) the planes might have even been assembled as needed and customization very common. –On a budget, beech; feeling proud, a few pence more, rosewood.

C. Gabriel mitre plane no. 220. –With rosewood infill, 10 1/4″ long with a 2 1/4″ iron. Mitre has thin 5/32″ wrought iron sides dovetailed to a thick 1/4″ blister steel sole. Stamp on the bridge is very weak, as a likely result of the relative hardness of the steel trade name punch used circa 1785-1790. Replacement iron.

With this low number plane, Gabriel resorted to etching the digits in, rather than stamping. 220 is the lowest Gabriel mitre number that I am aware of, and if these are production numbers, then it makes this example the earliest. After more than 200 hundred years, the original inscription has been overwritten at least once, but a fair amount of the original Gabriel signature is still visible. G__RIEL can still be seen. ‘E’ doesn’t show as well as it could in this photo. This Gabriel mitre plane is clearly marked with 220; many of the relatively few surviving marked Gabriel mitres are numbered. As far as I know, no one definitively knows what these numbers represent.

It is the embossed type, similar to some of Gabriel’s stamps for his wood planes. This stamp was obscured by oxidation for years. Both stamps into the metal on no. 220 are partially legible, and therefore, only partially successful.

Gabriel No. 239

Gabriel’s Mitre plane No. 239 has several interesting aspects:

- It has a bridge with “No” in script similar to same in Gabriel’s ledger.

- Signature of “William Barnett” a joiner who apprenticed in 1757 or 1777.

- Rosewood infill, screwed to the sides.

- Rear dovetails incorporated into part of heel after assembly.

There were two William Barnett entries in “Joiners’ Company Records 1640-1821,” BIFMO, 1757 and 1777. It would seem more likely that a joiner established for 20 years would be in a position to purchase an expensive Gabriel mitre plane, rather than a young man straight out of a 7 year apprenticeship.

Gabriel No. 270

This example is 10 1/8″ long and has an early 2 1/4″ James Cam iron. The wedge and infills are walnut, and the front infill is stamped Gabriel, with the same stamp that is used on many wooden Gabriel planes. No. 270’s bridge is 1/8″ thick with a crescent indentation, and the wedge underneath mirrors that shape. 391’s bridge and wedge have a similar configuration.

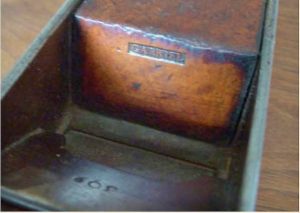

Front infill of no. 270, showing embossed GABRIEL stamp. Nos. 220 and 394 have identically shaped front infills as this one.

Gabriel No. 309

Here is Joel Moskowitz’ description of Gabriel No. 309, which he wrote about in his 2010 blog entries:

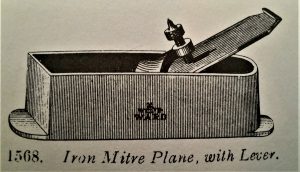

The first thing that struck me about the Gabriel mitre plane is that, even though this plane is a very early example of the genre, it shares the same construction common to all English dovetailed steel mitre planes. It’s 10 3/16″ long overall (at the sole), 1 3/4″ high, and 2 5/8″ wide with a 2″ iron by I. Sorby. The iron is certainly not original to the plane.

The sole is made from blister steel and is rather thick, about 1/4″ the sides are bent from much thinner, about 5/32″ wrought iron. The metal stock would have been purchased already rolled out. The only tools that would have been used in its construction, aside from possibly bending the sides hot with a forge and anvil, and maybe doing the peening hot, would be a hand powered drill, metal cutting chisels, a hacksaw, and a myriad of files. In addition, to smooth the edges or the iron, a hard steel burnisher would have been used instead of abrasives.

Gabriel mitre plane no. 309 with beech infill. Bridge stamped 309, and GABRIEL stamped on front infill. Photo by Joel Moskowitz, Tools for Working Wood.

The dovetails on this plane are not perfectly symmetric from side to side which suggests that the dovetails on the sides were laid out and cut before the iron was bent, and then the sole was laid out from the sides. The sole is made of two pieces of steel. A twenty degree slope was filed on the rear piece and and the front and rear are tongue and grooved together. The mouth is about 1/32″ wide.

A plain bridge was added and then the entire unit was assembled and peened together. By making the sides from soft wrought iron, and the sole from much harder blister steel the craftsman could ensure that most of the distortion to the metal happened to the sides, and the sole would not get dinged up and need extensive post peening work. Then the plane was infilled.

Gabriel mitre no. 309 with embossed Gabriel stamp into beech front infill. Infill is plain, without contours on the back, which is typical of some early mitres. Photo by Joel Moscowitz.

Gabriel No. 370

Not every Gabriel plane is a beauty. Numerous examples show 200 years of neglect, abuse, and ill-informed ‘restoration.’ Here is Gabriel No. 370, which sold in the July 2021 D. Stanley Auction. Photos by D. Stanley Auctions.

Gabriel No. 370 was purchased at the July 2021 Stanley Auction by a knowledgeable and skilled collector who has plans to restore this plane in a historically correct manner. I look forward to seeing the results.

Gabriel No. 372

This plane was sold in the October 2017 MJD auction as a Spiers mitre. Then it was sold by an ebay seller who also represented it as a Spiers. It was in rough shape, with pitting and a chasm for a mouth. Otherwise, it was fairly similar to Gabriel 391, with rectangular tenons attaching the bridge to the cheeks, and beech infills.

Gabriel no. 372 mitre plane, with plain beechwood infill, with no moulding at the back. Front infill is the same as Gabriel mitre no. 309. Photo from Ebay, 2017.

Gabriel mitre plane no. 372 as it appeared in the MJD auction in October 2017. Clearly, it has a replacement wedge. Aggressive cleaning did not improve the corroded plane body. Photo by Martin Donnelly tools.

I could not bring myself to pull the trigger on Gabriel 372.

Gabriel No 391

Gabriel mitre plane No. 391 was not recorded by Mark Rees in 1996. This is a solid mid-period Gabriel mitre plane with 3 dovetails in front of the mouth and four dovetails behind, on both sides. The rear flange is longer than that on other examples, and the beechwood infills are screwed into place.

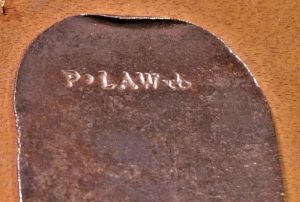

Gabriel 391 has an original 18th century iron by Phillip Law of Sheffield (1787-1833). The famous Seaton toolchest purchased from Gabriel in the 1790s, included some chisels by P. Law.

Gabriel No. 492

Gabriel Mitre plane No. 492 was noted in the book “Christopher Gabriel and the Tool Trade in 18th Century London,” by Jane and Mark Rees. 10 1/4″ long, with a 2″ cutter. Also in the book “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David R. Russell, no. 870.

The Marples iron logo stamp shows a single shamrock, which would date it between 1862 and 1875, when the triple shamrock logo was introduced. In general, the nibbed iron started to appear in the late 1840s, with makers such as Spiers, Cox, and Moon.

Gabriel No. 530

On 16 April, 2021, at Stride & Son Auction in Chichester, England, Gabriel’s No.530 mitre plane was sold. Originally, the auctioneer’s estimate was £30-£40, but after a flurry of bidding, Gabriel No. 530 sold for £3800. With a buyer’s premium of 18% and tax, the price of this plane was upwards of $6,500.00. Although Gabriel 530 was described as having a walnut infill and wedge, the grain appears to be aged beech. The front and rear infills are screwed into place at the toe and heel, and the crescent recess into the bridge shows a slight bevel.

Gabriel No. 530 mitre plane, as it appeared in the 16 April 2021 Stride & Son Auction, in Chichester, England.

Closeup of bridge, on Gabriel No. 530 mitre plane. Photo from Stride & Son Auction, Chichester, England, April, 2021. Photo from Stride & Son Auctions, Chichester, England.

Iohn White Cast Steel plane iron, from Gabriel no. 530 mitre plane. Photo from Stride & Son Auctions, Chichester, England.

£3800. Was it worth it? No, if the winner of Gabriel No. 530 has buyer’s remorse. Yes, if the winner has a deep appreciation of their new acquisition.

Gabriel No. 700

Gabriel mitre plane, signed and numbered with 700. The rosewood front infill has an interesting reeded adornment. Gabriel mitre plane no. 701 has a similar descending reeded moulding on the front infill.

Gabriel no. 700 (rosewood) and Gabriel-type mitre plane (walnut) with reeded front infills and cheesehead screws through front plate into the toe infill.

These two planes, along with Gabriel no. 701, probably came from the same production batch. No. 701 also has a cheesehead screw on the front, to secure its reeded infill. Common practice at the time was to have a handcut flathead screw countersunk into the front plate. The bridges on both of the above planes are thicker than the earlier Gabriel mitre planes, at ~3/16″ and the crescent shaped indentation has a smooth bevel along the edge. The earlier Gabriel mitres shown here, 220, 239, 270, and 391 have 1/8″ to 5/32″ thick bridges with no bevel at the crescent.

Gabriel no. 700, left, and unmarked Gabriel mitre plane with reeded moulding on front infill and similar profile at the rear.

This Gabriel reeding plane is of a general type that would have been used to make reeded mouldings. More specifically, the type of plane that was probably used to cut the Gabriel infills was a multiple reed plane. From “British Planemakers from 1700,” by W.L. Goodman, third edition by Jane and Mark Rees.

The development of the reeding plane required improvements in the construction of moulding planes in that they have many quirks, all of which need to be boxed if the plane is to be accurate and long- lasting. In some cases full boxing became the preferred option. The Gabriel firm seemed to be at the forefront of these developments…[c. 1780].

Gabriel Mitre Planes: Stamped and Unnumbered; Unmarked

This mitre plane was sold in a David Stanley auction in 2013, and was stamped Gabriel without a number. Photo from David Stanley auctions.

Gabriel mitre planes can be divided into three categories: those that are marked GABRIEL and numbered, those that are stamped GABRIEL only, and those that are unmarked but show sufficient build details to be attributed to Gabriel.

Typically unmarked and unnumbered Gabriel mitre planes show later characteristics, such as 2 dovetails in front of the mouth, and 3 dovetails behind the mouth.

Gabriel Mitre plane, in gunmetal, 8 inches long.

The infill is Cuban mahogany, and I photographed it on green to approximate its true red color. Unusual features include the use of gunmetal for the sides, contrasting iron used for the front plate, and it’s overall size, eight inches. Most Gabriel mitre planes are around 10 inches long, with iron widths ranging from 1 7/8″ to 2 1/4″. The iron in this example is 1 7/8″ wide. Like several other Gabriel mitre planes, there is no moulding at the rear of the toe infill.

Gabriel Mitre plane, stamped on bridge without number

Bridge is stamped GABRIEL. 10″ long with a 2 1/16″ iron by Ibbotson. This is another example of a Gabriel mitre without a number. Previously in the collection of the late David R. Russell, no. 871 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” and now in the possession of Joel Moscowitz, Tools for Working Wood.

Gabriel Bit Brace

A diversion from planes: a rare Gabriel bit brace, made of beechwood, with incuse GABRIEL stamp, rosewood handle, and button lock chuck.

From “Christopher Gabriel and the Tool Trade in Eighteenth Century London” by Jane and Mark Rees:

The number of braces (stocks) and parts of braces included in the two inventories is evidence that these were a regular product of the Gabriel workshop. We have examined four marked braces during the preparation of this publication, three plain, and one plated. We are aware of at least two other braces by Gabriel that we have not seen and suspect that there may be others.

Another marked Gabriel brace was included in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David R. Russell, no. 1430, on page 470.

Gabriel Mitre plane, in ebony, with stamp on bridge

Below is a later Gabriel mitre plane, with a thicker bridge, and a bevel at the crescent recess. It has two dovetails in front of the mouth, and three behind, on each side. It was marked on the bridge, without a number. The stamp looks similar to that used for the bit brace shown above, with extra space between the G and the A.

Later Gabriel mitre plane, ebony infill and wedge; James Cam iron. From the collection of James Claussen.

James Claussen asked me to bring along my ebony Gabriel mitre shown above in order to compare it side by side with his Gabriel mitre shown here. There are many similarities.

In the background, is a 3 inch New York style plane (bevel down), next to it is a small Tollner (Thorested) mitre plane, and the partial image in the corner is a 5 inch Brandt mitre. All planes from the fabulous collection of James Claussen.

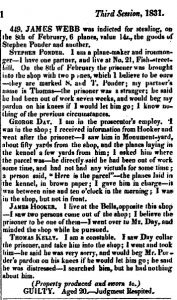

Stephen Ponder Planemaker

Stephen Ponder took over the 31 Banner St. Gabriel tool business around 1823, and continued to make planes at Fish St. Hill from 1825 until 1833. The plane is marked “PONDER” on the front plate. It is 10 1 /2″ long with a 2 1/8″ J. Fearn iron. This gunmetal Ponder mitre plane was included in Antique Woodworking Planes, by David R. Russell, no. 872. Construction and details of the plane appear more or less similar to those of Gabriel. Decorative recess on bridge is less rounded than those of Gabriel, however, and that detail is also observable on some other English mitre planes from the first third of the 19th century.

Stephen & Thomas Ponder gunmetal mitre plane. Front infill, showing makers’ stamp. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, April, 2022.

Stephen & Thomas Ponder gunmetal mitre plane, 10″ x 2 1/4″. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, April, 2022.

Stephen & Thomas Ponder gunmetal mitre plane, with Cupid’s Bow bridge. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, April, 2022.

From circa 1810, and through the1840s, the Cupid’s Bow bridge was very much in fashion. Early makers who sometimes incorporated the Cupid’s Bow into the bridges of their planes included: Thomas Moon, Robert Towell, John Smith, Edward Cox, and George Kerr.

After Gabriel

While the following mitre plane looks similar to a Gabriel in many ways, I believe it is later, probably 1830s or 1840s. A major clue here is the bridge, which no longer has the crescent shaped rounded recess, but a cutout with a longer straight edge, with corners at each side. This type of bridge can be found marked with makers such as Ponder, Moon, Smith, or unmarked, such as in this example. Another clue with this plane is in the Moses Eadon snecked iron with it. The Eadon iron dates from the 1830s.

3 Bridges compared: pre-Gabriel c. 1760-1780; Gabriel period c. 1780-1822; post-Gabriel c. 1823-1850.

One of the advantages of collecting is the ability to compare examples side by side. Sometimes only then, do the significant differences really sink in. Seen individually, the pre and post-Gabriel planes could easily be mistaken (and have been) for Gabriel.

Gabriel’s Wharf

Thomas Gabriel and his successors occupied Gabriel’s Pier and Wharf off of Commercial Road in Lambeth, from 1815 to c. 1930.

Gabriel Wade and English, Limited continued to trade as late as 1968 in other locations.

JOHN SYM PLANEMAKER

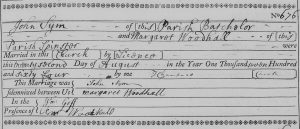

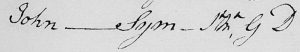

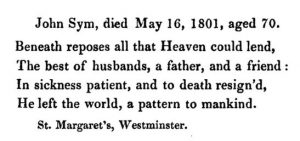

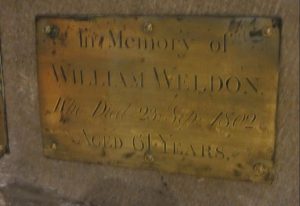

John Sym, a prolific producer of wooden planes, also made some of the first English metal mitre planes. John Sym apprenticed to David Lucas, a joiner, in 1753. He was admitted to the Freedom of Joiners’ Company, and took on his own apprentices, including James Higgs (1772), and John Davies (1784).

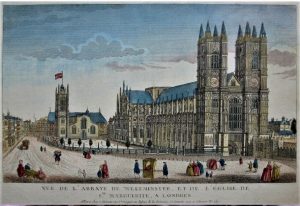

John Sym Baptism 10 October, 1731, and birth, 29 Sept, 1731, St. John the Evangelist, Smith Square, Westminster.

W. Simms must have been related to John Sym, with an alternative spelling of their surname. These surname spelling variations were common in the 18th century.

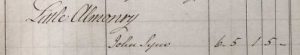

Tax assessments were made for John Sym throughout his entire working life, and he was universally levied the “poor rate” for all of them. These assessments ranged from 1762 to 1801. Almonry, Little Almonry, New Tothill street (a short two block street running perpendicular to Tothill St.), and Dean Street West, were given for Sym’s workshop.

C. & J. Greenwood Map of London, 1826. Detail of Westminster: Almonry, Tothill St, New Tothill St., and Dean St.

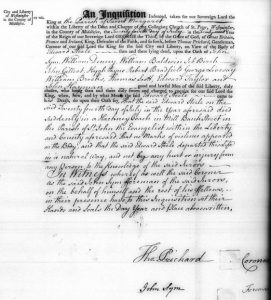

“City and Liberty

of Westminster

in the County of

Middlesex .}

to wit.An Inquisition Indented, taken for our Sovereign Lord the

King at the Parish of Saint Margaret

within the Liberty of the Dean and Chapter of the Collegiate Church of St. Peter, Westminster ,

in the County of Middlesex , the Twenty fourth day of July in the Twenty second Year

of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord GEORGE the Third, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain,

France and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, and so forth, before Thomas Prickard , Gentleman,

Coroner of our said Lord the King for the said City and Liberty, on View of the Body of

Edward Steele then and there lying dead, upon the Oath of John

Sym , William Denny , William Baldwin , Job Birch

John Gillcot , Hygh Payne Robert Bradfield George Livesay

William Brooks , Thomas Scott , Edward Taylor and

John Hayman good and lawful Men of the said Liberty, duly

chosen, who being then and there duly sworn and charged to enquire for our said Lord the

King, when, how, and by what Means the said Edward Steele came to

h is Death, do upon their Oath say, That the said Edward Steele on the

said Twenty fourth day of July in the Year aforesaid died

Suddenly in a Hackney Coach in Mill Bank Street in

the Parish of St. John the Evangelist within the Liberty

and County aforesaid, That no Marks of violence appeared

on the Body, and that the said Edward Steele departed this Life

in a natural Way, and not by any hurt or injury from

any Person to the Knowledge of the said Jurors

In Witness whereof as well the said Coroner

as the said John Sym Foreman of the said Jurors,

on the behalf of himself and the rest of his Fellows,

in their presence have to this Inquisition set their

Hands and Seals the Day Year and Place abovewritten,

Tho. Prickard [mark] Coroner

John Sym [mark] Foreman”

24th July, 1782.

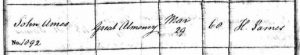

John Ames

John Ames took over John Sym’s planemaking business in 1800. Ames was born to John Ames Sr. and Elizabeth, on 2 September, 1776, and was baptised at St. James, Westminster, on 16 September, 1776.

| Roland AMES | LONDON (U.K.) |

| 25 Tothill St., Westminster | 1852 |

From British Planemakers from 1700, by W. L. Goodman; 3rd Edition by Jane and Mark Rees:

“Son of planemaker John Ames. This business was the continuation of John Sym [starting in 1800]. The business was varied, as evidenced by the 1837 and 1842 P.O. directories which noted “Saw mills for Brush-Board, Cartridge Boxes etc.” at the Great Almonry premises and “Plane, saw and general tool manufacturer” at the Tothill St. address. In 1859 James Syme is recorded as being at 25 Tothill St.

It appears that the business of Joseph Sims was incorporated into the firm around 1834 and there are also a few planes with the additional mark of J. Davis. Both these firms were later acquired by A. Aitkin & Sons. Planes from this maker are common.”

Joseph Sims and James Syme were almost certainly related to John Sym, and their names were variations of spelling the surname. This practice was common for the period.

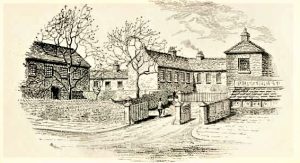

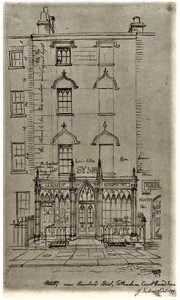

Sym’s cabinet shop over on Tottenham Court Road. Drawn by George Scharf Sr. in 1833. Probably run by the Sym extended family.

Speculation about the relatedness of these three planemakers. At this point, I am not ready to drill down and figure out how they were related exactly. But it does make me wonder if production of metal planes was continued after John Sym’s death in 1801.

Sym’s Cabinet Shop was located near the intersection of Howland Road and Tottenham Court Road. This was 5 blocks north of Joseph Buck’s Tool Warehouse (after c. 1838 George Buck’s) established circa 1832, at 245 Tottenham Court Road..

James Syme

James Syme did not produce large quantities of metal infill planes, but he was at the forefront of their development during the 1850s. Syme produced some of the earliest shoulder, chariot, and bullnose planes before that decade came to a close. A Syme bullnose plane in gunmetal (no. 830) is shown in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David R. Russell.

Syme bullnose plane alongside a Buck (rear) that was most likely also made by Syme. Photo from George Anderson

An 1853 assessment tax for James Syme at 25 Tothill St. gave him the “poor rate.” In 1869, another assessment was levied to Syme, 25 Tothill St., for “general, sewer, and special rates.”

James Syme, 1856 London Postal Directory. Syme offered “general mechanical tools” as well as the metal planes he was known for.

Shoulder plane, in miniature form, by James Syme. Four inches long with a 1/2 inch iron. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions. March 2009.

Syme, having introduced the shoulder plane, brought this form to an elegant and refined state. Symmetry was a fundamental component of this elegance. Examples such as this plane served as inspiration for makers on the other side of the Atlantic, such as Joseph Popping in New York during the early 1870s. Gunmetal body and rosewood infill.

An unusually short, early lever cap, perhaps done to avoid clearance issues with the brass nut on the cap iron.

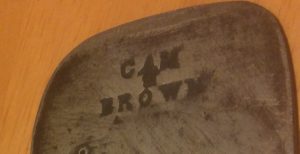

SOME EARLY ENGLISH PLANE IRONS

A review of early English metal planes would be incomplete without including some plane irons. Early English mitre planes carry much history, and sometimes retain their early Sheffield and Birmingham plane irons.

The early plane iron stamps were one line only. “James Cam; Warranted; Cast Steel” (middle) consisted of 3 separate stamps, probably because the stamps were made of softer metal in this period. Cam iron (right) has 2 stamps; “Warranted Cast Steel,” is an early 2 line stamp. Round top on this iron looks to have been chopped out with a metal chisel.

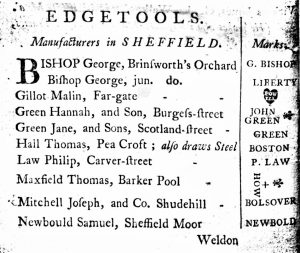

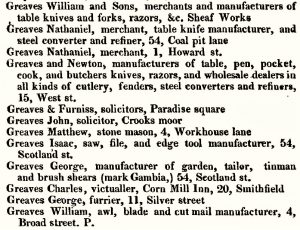

Benjamin Huntsman invented the crucible steel (cast steel) process circa 1740-1742. By 1787, a number of Sheffield edgetool makers had integrated this method, but did not adopt the “CAST STEEL” stamp until the early 19th century.

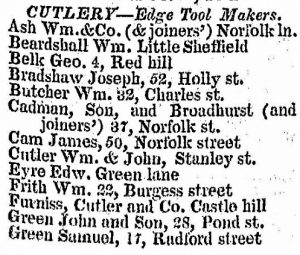

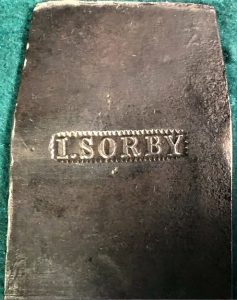

In 1787, there were relatively few edge tool makers in Sheffield. By the early 1800s, many new edge tool makers had entered the field. In Baines’ 1822 Directory, there were listed two distinct Sorby businesses: J. Sorby & Sons, 26 Spital Hill, and Sorby, Turner, and Co., Wicker.

The following quote came from Simon Barley (backsaw.net 19 June, 2013), regarding the the Sorby family of edgetool makers:

Early one-line stamp of I. Sorby. This stamp belonged to Sorby, Turner & Naylor, who later registered the “Mr. Punch” trademark. Photo from ebay, 2020.

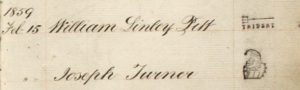

Joseph Turner registered the “Mr Punch” trademark for the I. Sorby edgetool brand on 15 February, 1859. Image from Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire.

David Ward’s early marks before “& Co.” in the 1830s. Circa 1805-1830. I. & H. Sorby early mark, introduced sometime after John Sr.’s sons, John & Henry Sorby, became active in the family edgetool business.

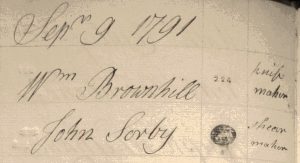

I. (John) Sorby, shear maker, registered the hanging sheep trademark, 9 September,1791. Image from Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire.

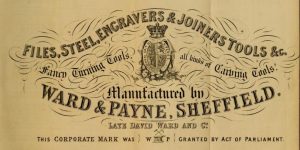

The partnership between David Ward and Henry Payne was established before 1843, when the Ward & Payne trademark was registered; Henry Payne was a Sheffield edge tool maker who appeared in directories by 1837. I suspect that the W.& P. “anvil and crossed hammers” was used before the mark was registered, possibly as early as 1837, since some original irons with the Ward & Payne mark appear on the bevel side, in Robert Towell mitre planes.

Henry Payne died in 1850, and ownership of the company reverted back to the Ward family, but the Ward and Payne trademark was retained.

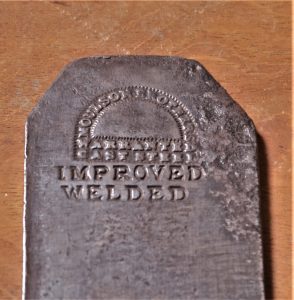

“IMPROVED WELDED” referred to the carbon steel edge that was welded to the wrought iron body of the plane iron. Most all English plane irons had a laminated edge in the 18th and 19th centuries–this was also true for chisels of the period. Blister steel, shear steel, and cast steel were all expensive (progressively), and it was less costly to engage the labor to weld a steel edge on to a wrought iron body rather than to make the entire tool from either of the three expensive types of carbon steel. By the early 20th century open hearth steel making had progressed to the point where making the entire plane iron from steel became economically feasible.

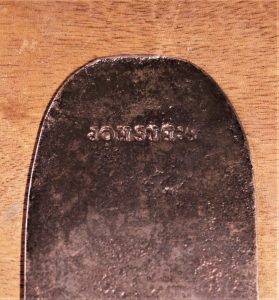

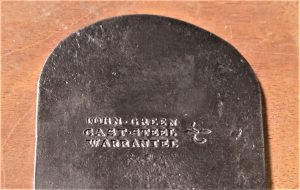

Iohn Green, early stamp, with fleur de lis, as shown in Gales & Martin 1787 Sheffield Trade Directory; Iohn Green Cast Steel Warranted (somewhat later); G. Wilkinson, Birmingham.

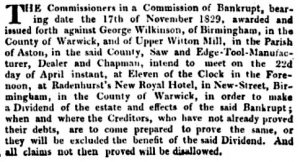

In the early to mid 18th century, Birmingham was a center for edge tool making. By 1770, Sheffield edge tool makers were dominating the field, and Birmingham tool makers concentrated on other tools, such as planes and rules.

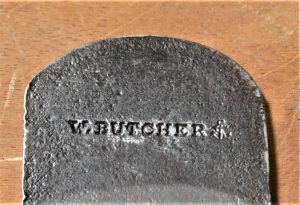

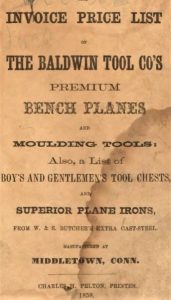

William Butcher was established in 1818, and listed in the Baines 1822 Sheffield Business Directory as working individually at 32 Charles St. I believe that the one line early styled Butcher plane irons, and early chisels with similar marks date from c. 1818-1825>. Butcher had several short lived partnerships in the 1820s, including Wade & Butcher, which was used on knives and razors, etc. into the 20th century. In 1828, Pigot’s directory showed Butcher, Brown, & Butcher. The second Butcher would have probably been William Butcher’s younger brother, Samuel, who was living in New York City by 1827, promoting Butcher edgetool products. In 1830, the business was formally named W. & S. Butcher.

Before John Sorby Sr. (1780-1829) passed away, his sons John Jr. and Henry had already taken control of the company, and the mark “I. & H. SORBY” was being used.

Butcher plane irons. l.to.r.: 1818-1828 (anchor); Arrow and Maltese cross 1840s-1920>; Baldwin/Butcher 1840s-1850s.

William Butcher, in the 1822 Baines Sheffield Trade Directory. Plantation tools would have been tools for the slave trade.

As the metal used for stamps became consistently harder, the stamps were made larger.

Robert Sorby Kangaroo Works iron, circa 1860, Ward & Payne iron, circa 1840s, and W. Peace iron, circa 1850s. Through most of the 19th century Sheffield edge tool makers offered slightly less expensive plane irons with steel laminations of blister steel or shear steel rather than “CAST STEEL” (crucible steel). These featured larger stamps which included the company logos. Most irons from this period had a cast steel edge.

Robert Sorby’s “kangaroo” mark was officially registered in 1850, although it may have been in use for a few years before that; by 1860, the kangaroo mark was distributed en masse.

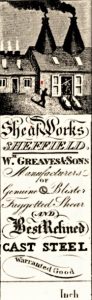

Greaves Sheaf Works Advertisement from the 1830s: Blister steel, Shear steel, and Cast Steel. From Sheffield City Archives.

The Greaves family was documented as working in the Sheffield Edgetool industry in the late 18th century, but by the 1820s, they had a strong presence in the City Directories. Isaac Greaves made most of the plane irons we see today, but William Greaves’ Sheaf Works also made tools, such as chisels, gouges, and some plane irons.

J. Herring & Sons (all steel) and Stormont Archer (Iron/cast steel laminate) plane irons, circa 1930.

Sometimes in the old days, when a person would blink during a photographic exposure, the eyes would be added in the darkroom.

UNMARKED MITRE PLANES

Large English gunmetal mitre plane, with 15 dovetails and one tenon, circa 1830. Towards the mid 19th century, mitre planes in England trended larger, and this mitre, featuring a 2 9/16″ Wilkinson tapered iron, is an example. Most of the larger mitre planes in this 1840-1860 period were cast iron, however. Many early mitre planes were unmarked, some of them were one-off amateur efforts, and others were done professionally within the trade at a high level of craftsmanship. While I generally prefer marked tools, this one caught my eye. The ogee arch on the bridge, was a design developed in ancient Persian and Moroccan architecture. In the Gothic Period, around the 14th and 15th centuries, the ogee arch spread to the British Isles. Quite popular in architecture, the full ogee arch never caught on in Western tool making, as compared to the ogee moulding. Full ogee arches can be seen in the 1865 photo of Kensington High Street in the section on John Smith.

The gunmetal body of this mitre plane is dark, and has never been polished. The bridge has a cupid’s bow on the top, while most mitre planes place the cupid’s bow at the bottom. There is an “X” signature engraved into the bridge, probably done by an illiterate owner. Many early wills and other documents were signed with a similar “X.”

The gunmetal sides of this plane are unusually hard and do not scratch or mar at all. It is interesting to observe the wide range of densities of various copper based alloys.

The early Green iron features a fleur de lis logo. The entire inscription could have been made with as many as 4 different stamps.

Mitre plane, marked “I. GREEN SHEFFIELD,” on the front infill. No. 866 in Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools,” and photographed in 2012 by David Stanley Auctions.

The example shown above has some similarities with no. 866 in Antique Woodworking Tools, by David Russell. Similar features include the bridge, front infill, and front flange. David Russell’s no. 866 was an iron bodied mitre plane with beech infill, however.

This plane was also stamped “I. Green” on the bridge as well as the toe (small lettering), according to David Russell. Unfortunately, the resolution is not good enough on this image file to show them.

The large mitre plane in the middle still shows file marks at the bend which probably occurred while making it.

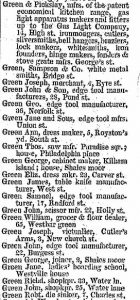

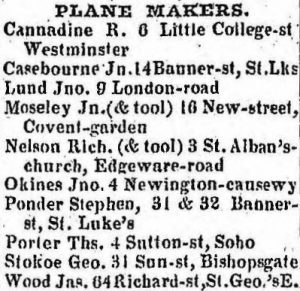

EARLY LISTINGS FOR LONDON PLANEMAKERS