Traditional square pod style wooden pianomakers’ brace as offered by Otto Bergmann GMBH of Berlin, in their 1927 Catalogue.

Hand-cranked bit braces are still used today for tightening large plate screws before pitch raising and general tuning, as this helps to secure pitch stability. Braces are also used to remove and replace plate screws when the large iron plate is removed during restoration for soundboard and bridge work. Standard steel ratchet braces are used for these structural related tasks, but before Black and Decker introduced the portable electric drill, hand braces and bow drills were commonly used for many lighter procedures. Braces specific to the piano industry were smaller, typically with a six-inch sweep or less, and were used for action work assembly and custom fitting of components, such as damper rails or case parts. High torque was not necessary, but speed was important because of the sheer magnitude of all the small parts assembly involving the turning of a threaded screw. Just imagine all of those little parts, 88 times for each.

This is a Goodell No. 230 screwdriver brace, six-inch sweep, with a specialized chuck that accepts tools with a 1/4″ diameter shank, the same size as most piano regulating tools used in the combination piano tool handle introduced around 1900. It is shown here changing out small for large let-off regulating buttons on a Steinway grand action. This is an early version of the 230 brace, with rosewood handles, and early 1890s thumbscrew.

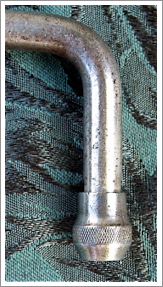

Close-up of chuck.

Goodell Pratt No. 230 Brace as shown in the Tuners’ Supply Catalogue (Hale) for 1930. Different compression nut, and handles made of Mahogany stained hardwood.

“This tool is designed for the use of…cabinet, carriage, organ and piano makers.” From The Iron Age, Oct. 5, 1893. No. 230 was actually developed by the Goodell Co. and the brace carries a Dec. 27, 1892 Albert D. Goodell patent on the lower part of the crank arm. This patent, however, was for another brace design. Goodell’s No. 230 Brace was also included in the Hammacher Schlemmer 1896 catalogue. The 230 brace was offered in a number of piano supply catalogs, including American Felt Co. and Tuners Supply between 1905 and 1930.

Goodell Pratt No. 230 Brace, circa 1930, with stained hardwood, updated thumbscrew, and larger metal base for handle. Photo by Sandy Moss, 2012.

New York Bow Drill, 11″, with ebony spool, rosewood handle, and Goodell chuck from their No. 230 brace.

Gabriel brace, shown here to serve as an example for modern piano technicians who may not be familiar with this type of design. This early brace and bit is not piano specific, other than through the random fact that Gabriel produced some piano parts in the 1790s.

Christopher Gabriel, c 1770-1822, early English wooden brace, with button lock type chuck.

A Gabriel brace has been found with integrated reinforcing brass plates on the body; this modification would have pre-dated 1822, which was earlier than previously thought.

Improved Scotch Brace, in William Marples 1861 Catalogue. Image from williammarplesandsons.com.

The “Scotch brace” depicted above was listed in Sheffield pattern books from the early 19th century as “Best Plain Brace.” Shortly after this, they became known as Sheffield Braces. Another possibility was that the author of the Birmingham trade book was all too aware that Sheffield had overtaken Birmingham’s toolmaking industry, and thus avoided naming the rival city. A few years later, the term “Improved Scotch Brace” was applied to a metal bodied brace, with facets, and an incorporated crank handle.

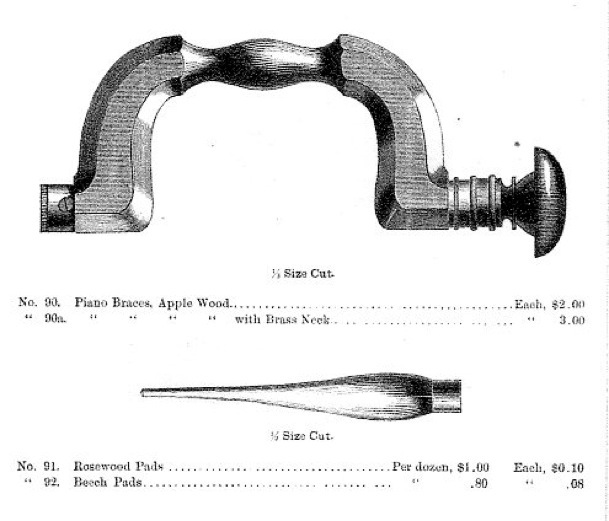

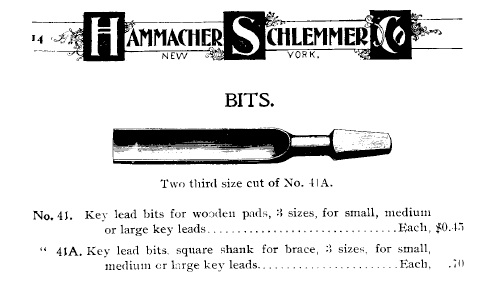

Hammacher Schlemmer catalog, 1885. The wooden brace shown below is the typical design for the piano brace, with the crank arm in the same general shape as the English Sheffield brace, but minus the reinforcing plates. These braces accept tapered cylindrical pads, not unlike a Morse taper, which was somewhat anachronistic for the late 19th century, compared to the Sheffield button lock or the more modern Barber/Amidon type chuck used on the steel American braces.

Hammacher Schlemmer catalog, 1885.

Sizes of the piano braces ranged from 8 to 12 inches, noticeably smaller than the average 14-inch Sheffield brace, and the sweep was usually around 5 inches, but could range from 4 to 7 inches. Applewood was used for the brace shown, which was often used for piano braces, but beech was more common for braces intended for general use. A brass neck, indicative of the higher-end braces, was a costly option here.

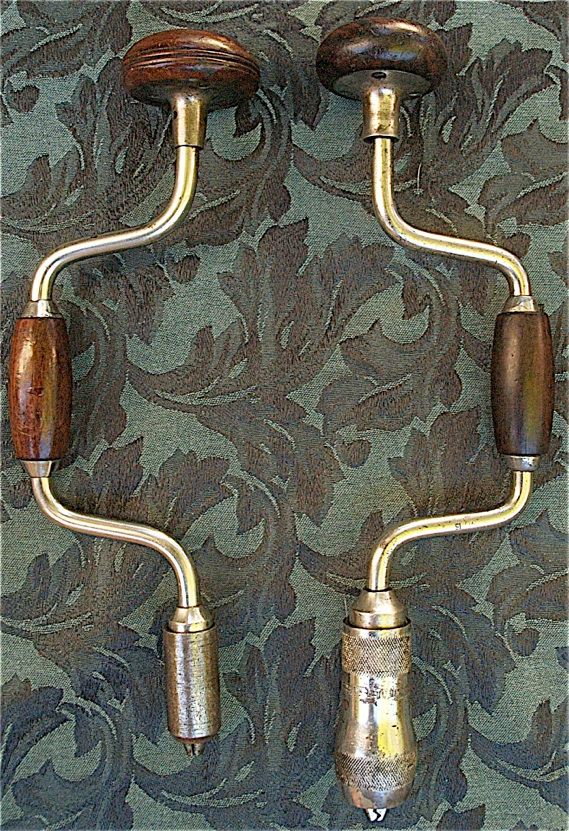

Two beechwood piano braces, with Morse taper style pads, but long pre-dating Steven A. Morse’s invention in 1864. The one on the right resembles the 1885 H. S. brace shown above, and the brace on the left, which accepts the same type of pads, shows more of a Dutch influence. These wood bodied piano braces were no longer offered in the catalogs after 1900.

Close-up of the lignum vitae handle with ivory plug.

Two more wooden piano braces. Bagshaw and Field in Philadelphia, PA, made the one on the left, with an applewood body and a lignum head. On the right is a piano brace with a body comprised of solid rosewood, with a pewter neck and ferrule. It is marked with the Star of David, but is not signed by the maker. Rosewood was seldom used for the complete crank arm of a brace because it was not common to source Brazilian rosewood stock that was large enough and sufficiently unflawed to withstand the strain during typical use. Erlandsen also made a beautiful rosewood brace not unlike this one. Both of these braces were higher end, and more expensive because of the wood used and the metallic necks; they’re also noticeably heavier than the ones shown above.

Bagshaw & Field applewood piano brace, and solid rosewood pianomakers brace, marked with The Star of David.

Mathieu, Paris Pianomakers’ brace with ivory handle and set of pods. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, March, 2013.

Mathieu, Paris piano brace (unmarked), with a Cormier wood body, 7-inch swing, and characteristic long brass neck or baluster. This one has a handle made of horn, probably from a water buffalo. Mathieu in Paris made the bow drill stock in the foreground, which has an identical baluster, but with an ivory handle.

In France, the two main makers of pianomakers’ braces were Aux Mines de Suede and Mathieu, who also made pianomakers’ bow drills, shown above. French pianomakers’ braces were characterized by having an extra long neck, with the stock made of cormier wood, and the socket accommodating tapered bit pads. In this case the braces are in cormier wood, but the pads are a mixture of oak and ash. While the braces may look like they are ‘tipping their hats’ to each other, that’s just a distortion of the camera lens; the cormier wood handle on the left and the buffalo horn handle on the right are perfectly level. These two French braces would have been what Léon Pinet would have had available to buy in during his years of doing business.

When the French tool company “Aux Mines de Suede” (From the Mines of Sweden) opened for business in the 1840s, the loss of the Napoleonic Wars and the battle of Waterloo (1815) were still within living memory. Given that, and the general rivalry between the British and the French over the centuries, it made sense to advertise Swedish steel over Sheffield steel, even though Sheffield was closer to Paris than Sweden.

By the 1860s, an appreciable amount of French cast steel began to be produced, part of which was used for the burgeoning French edge tool industry.

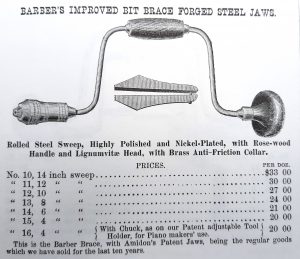

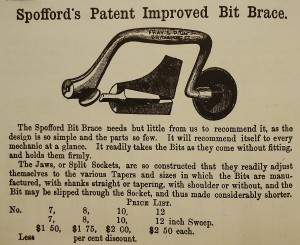

Millers Falls, an early leader in manufacturing bit braces, made two uniquely small ones with a 4-3/4″ sweep, numbers 15 and 16, which was the narrowest sweep of any mass production steel braces. This series of braces had no ratchet mechanism, as it was introduced before that feature became standard, the absence of which made the small sweep more important for clearance issues in close quarters. The revolving weight of the ratchet also would have made the tools more cumbersome.

No. 16 brace, designed for pianomakers, had a small chuck, the same as what they put on their adjustable tool holder. This made the brace lighter, quicker, and easier to work with agility for action assembly and other lighter, repetitive tasks. The narrow sweep also enabled more precise work with the driving, rotating handle placed closer to the work as compared to braces with larger swings further offset. In addition to all of the proprietary tools made for adjustable handle, the jaws of this chuck could accept and hold just about any tool, including tang ends and round ones. Millers Falls advertised this feature in their catalogs.

Number 16 was made from 1884 to 1901, and No. 15 with the standard Improved Barber chuck, was made from ~1876 to 1922. The No. 15 had the same versatility, but with the heavier and more robust chuck, and was most likely also used in the piano industry before the introduction of portable electric powered tools introduced after World War I.

These braces were not included in the piano supply catalogs that I have seen, but are shown here in the 1887 Millers Falls catalog, with the intended application for piano work duly noted. Schley and Co., a piano supplier in NY, did offer the general line of Millers Falls braces in their 1905 catalogue.

Millers Falls Numbers 16 (1884-1899) and 15 (1876-1922) braces with 4-3/4″ sweeps. Number 15 has the improved Barber chuck with McCoy’s jaws, and small rosewood head. Number 16 has a special combination tool handle chuck and small lignum vitae head. Both braces have McCoy’s rotating wrist handle in rosewood with brass rings inside the handle to avoid splitting. Top handles for both do not ride on ball bearings, the only two in the 10 to 16 Barber Improved braces series that lack that feature, probably because the handles were too diminutive to allow sufficient space. On No. 15, the crank handle has less of a taper at the ends, and has slightly more play than that of the No. 16. While the two braces share the same sweep, the profile of each is different: the nickel plated steel frame of No. 16 has more lazy curves as compared to those on No. 15. No. 16 shown here dates from around the same time as the 1887 catalog, and the No. 15, with McCoy’s Feb. 18, 1890 patent date on the shell, and rosewood head, was made approximately ten years later.

Millers Falls Nos. 16 and 15 pianomakers’ braces.

Three Millers Falls chucks disassembled, showing jaws, compression nut or shell, and receptacle for the jaws which is threaded on the outside for the adjustment of the shell. At the top of the photo is the smallest chuck from the No. 16 brace. In the middle is a little larger chuck which is marked with the Jan. 14th 1868 Amidon patent; it belongs to the Millers Falls adjustable handle. Apart from the different sizes, there are some very minor differences between the No. 16 chuck and the tool handle chuck, which are apparent in this photo, but the function is the same. Jaws on the No. 16, however, appear to be slightly more adapted to accept rounds rather than square bits, as compared to the jaws of the combination handle. Adjustable handles were offered in a number of piano supply catalogs including the large 1911 American Felt Co. catalog. Shown at the bottom of the photo is the chuck from No. 15 brace, with the standard Improved Barber chuck, and spring loaded alligator jaws.

Three Millers Falls chucks disassembled.

Pianomakers’ Brace, rosewood, with Millers Falls No. 16 Chuck. Photo from Brown Tool Auctions, October, 2023.

In addition to the bow drill, hand braces were also used for pinblock drilling (!). This would have been used in a brace like the Millers Falls No. 15. The narrow sweep of the brace would reduce the amount of pull off-center, and also enable quicker revolutions, for this large repetitive task. Hammacher Schlemmer, 1900.

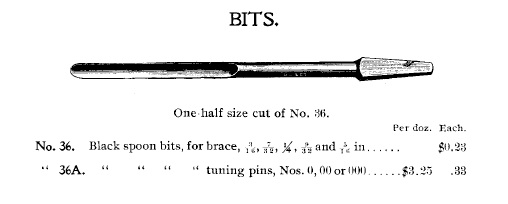

Spoon bits for use in brace with standard chuck, such as M-F No. 15; sizes for drilling out pinblocks/wrestplanks for tuning pins.

There are many countersunk screws in piano cases.

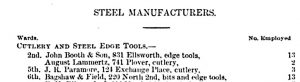

Bagshaw & Field, and Booth & Son, both recorded with 13 employees in “Census of Philadelphia Manufacturers,” by Lorin Blodget, in 1884.

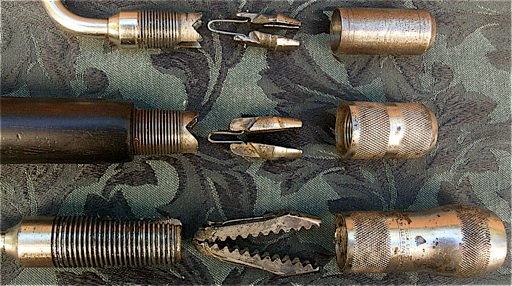

Three spoon bits for bit brace with standard chuck: Top one was unmarked, middle one was made by Hilger, and bottom one, a combination drill and countersink, was made by Bagshaw and Field in Philadelphia. They employed 13 people during the 1880s, according to the Census of Manufacturers of Philadelphia written by Lorin Blodget in 1884.

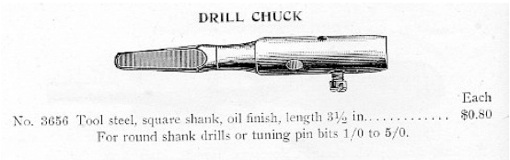

Another option was this drill chuck with set screw. This type of chuck was also used in a handmade combination handle for regulating tools. c. 1905.

Drill Chuck, catalogue,c.1900.

Bits for drilling out keysets for lead weighting. Erlandsen manufactured most of the specialised piano manufacturing bits, and they are listed as Erlandsen’s in the 1905 Schley piano catalog. Tapered square shank for conventional chucks, and the older type, with a tang, for fitting in wooden pads for the traditional wooden piano brace. By 1900, the latter was in the process of being phased out, but since traditional craftspeople held on to their expensive tools for years, this was probably a long process.

Bits for drilling out keysets for lead weighting. Erlandsen. H.S. 1904 Piano Catalogue.

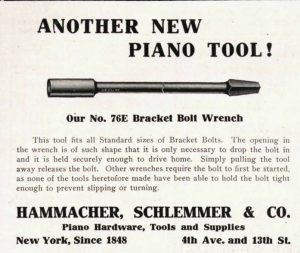

H.S. & Co. N.Y. advertisement for Action Bracket Bolt Wrench for piano brace. “Music Trade Review,” 1913.

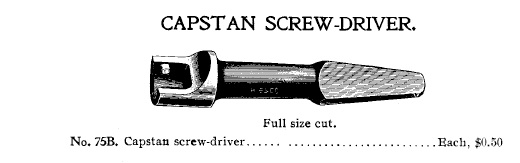

For installing capstans in the back of keys. H.S. 1904 Piano Catalogue.

Fray 108 brace found at the Hornung Estate in 1990. This is a Spofford style brace, with a clamshell screw clamp for holding the bit. It’s very effective, but a practical way to apply a ratchet mechanism was never developed. The alternative chuck, and the attractive two piece rosewood crank handle, held together with pewter rings, make this brace increasingly in demand between collectors. Although this brace was intended for general use, the boring and screwdriver bits that it was found with indicate that it was used for plate installation for their upright pianos. This would be done with the piano back, i.e., wood beams/soundboard/pinblock assembly, laying horizontally on a truck, without the cabinet sides or keybed. Therefore, no clearance issues were present, and a ratchet brace was unnecessary.

Fray 108 brace found at the Hornung Estate in 1990.

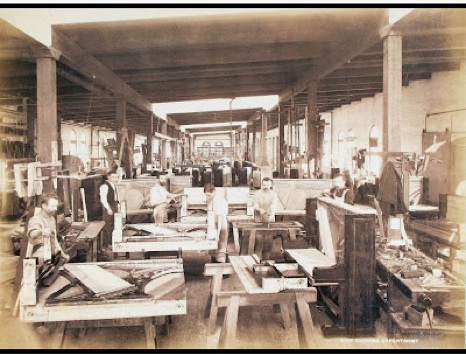

Blasius Piano Factory.

Blasius piano factory, c. 1895. Here you can see the piano back assembly on sawhorses. In other factories, these could be rolling trucks to advance the instrument from one work station to the next.

From Arthur Reblitz, “Piano Servicing, Tuning, and Rebuilding.”

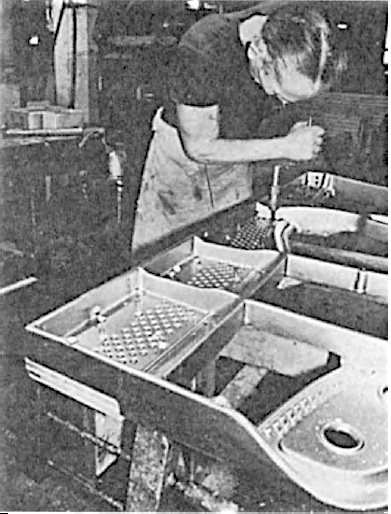

Andrew Boisvert (March 22, 1917- April 22, 1991) attaching a freshly fitted pinblock to the iron plate of a new Knabe grand with plate screws driven by bit brace. This was in the Aeolian American factory in Rochester, N.Y. during the mid-1970s. Lots of leverage and strength was required to drive those large screws into dense layers of hardrock maple, so a brace with a larger swing was used. It is no coincidence that Boisvert appears to be wiry and in good shape, which was common for active craftspeople in past generations. Note the wood clamps pressing the pinblock snugly up to the plate flange; the pinblock has been carefully shaped and mated to this flange, finishing up with a spokeshave. A good fit is critical for tuning stability. In the last several decades this procedure has become widely practiced amongst piano technicians using various methods.

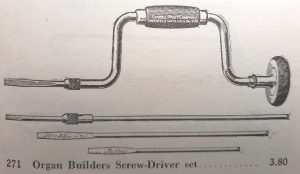

Stock photo of an antique organ builder’s dedicated screwdriver brace. The long extension was used to reach difficult places. Given the availability of this type of tool in piano supply catalogs for several decades, I believe there was was overlap with piano applications.

Unusually small version of a gentleman’s brace, with long screwdriver bit, in a configuration like the above, but considerably more versatile, with interchangeable bits. The brace alone is 8-1/4″ long with a very narrow sweep. A larger version of this type of brace, with a bulbous crank handle was in general use in the 18th to mid 19th centuries.

Unusually small version of a gentleman’s brace, with long screwdriver bit.

This very light and long piano tuner’s brace was included with a set of piano tools dating from the early 1900s. This delicate type of brace is uncommonly found, but I’ve seen a number of them over the years. The brace without bit is 12″ long with a 4″ sweep.

Millers Falls No. 64 offset screwdriver.

An unusual “Super Simplex” screwdriver from a tuner’s tool kit circa 1920. Rather off balance in appearance, it does not seem to be bent. It’s small enough for one hand to hold both the handle and the offset portion, giving additional leverage. This tool was made by Millers Falls and was actually the no. 64 offset screwdriver.

Drummond interchangeable screwdriver brace.

Decorative, stationary cap on handle showing patent date. This was designed to reduce friction on the palm of the hand during rapid revolutions.

Drummond interchangeable screwdriver brace, patented January 18, 1870. Extra bits were made to be fixed on the screwdriver blade. Here is Drummond’s 1870 patent.

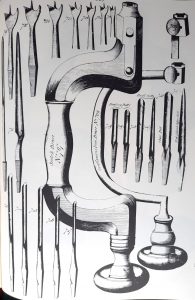

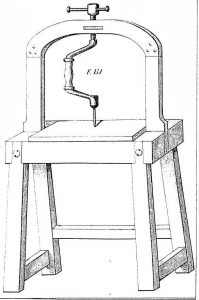

A hand drill press depicted in Siever’s Il Pianoforte… 1868. This fixed press was used for heavy structural work, and would sometimes require two workmen to drill large holes in thick stock, according to Sievers. With steam power available for piano factories, for several decades before 1868, it seems like a description of work that was becoming outdated by the time this book was written.

Diminutive oak brace, 4″ sweep, accepting round pads. In the form of a crooked stick type brace, but the grain is quite straight.

Primitive crooked stick braces, typically made before the Industrial Revolution, would have utilized an existing appropriately curved hardwood stick, in the same basic shape as above. The reinforcing band or ferrule (made to counter torsional stress on the body of the brace while driving) and permanently attached bit would have been handwrought iron and fabricated by the local blacksmith.

General purpose pod bits were typically made with a square shaped peg, and a collection of these square pod bits was preserved from the Dominy family of craftspeople in Long Island c. 1760-1840, and are displayed at the Winterthur Museum.

Dutch brace, with built-in extension and permanently affixed spoon drill bit. This old brace probably dates before 1850, when interchangeable bits for braces became more of a universal standard. In this case, a separate brace would be needed for each task. Twelve inches long with a four-inch sweep.

Dutch brace, with built-in extension and permanently affixed spoon drill bit.

E. Mills Philadelphia pianomakers’ brace. Formerly Booth & Mills. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auctions, October, 2022.

Even as late as 1959, Fletcher & Newman piano supply in the U.K. was offering a 5″ sweep brace in its catalogue. “Braces as above with 5″ sweep, made especially for working in confined space and carrying in bag.”