© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries

MORE AMERICAN MITRE PLANES

Early Development of Leonard Bailey’s Mitre Plane

Early iteration (version 2) of the Bailey no. 9 Cabinet Makers Block Plane (or Pianomakers’ Mitre Plane). This one has the Aug 31, 1858 patent date, which covered his new lever cap with a cam lock, operated by a thumb lever. It’s not hard to see why Bailey changed the “broomstick” handle. Shown below are 8 photographs, taken by Jim Bode in June 2019, of a Bailey no. 9 mitre plane, version 2 (c.1858-1866), with a modified Moulson Bros., Sheffield iron.

Much of the detailed information shown here, regarding the incremental development of the Bailey mitre plane came from reading “Leonard Bailey and his Woodworking Planes,” by Paul Van Pernis and John G. Wells, published in 2019.

Leonard Bailey worked at the Church & Lane Pianoforte Case Factory in Winchester, MA from 1853 until early 1858. Cephus Church and Joshua Lane established this factory in 1847 on Canal St. Church & Lane does not show in the Pierce/Michel Piano Atlas because they did not make whole pianos, just upright and square cases.

Church & Lane were recorded in the Massachusetts State Census of 1855 with 27 employees, so this photograph likely showed their entire staff.

Early Leonard Bailey Boston spokeshave, circa 1850s and 1860s. Patented 1858.

Bailey’s experience in the piano industry informed his early production work, as he offered veneer scrapers, spokeshaves, and mitre planes along with his split frame bench planes in the late 1850s, and 1860s. Iron spokeshaves were Bailey’s biggest seller, and he found a ready market for them with workers from the large shoemaking industry in Massachusetts during the mid-19th century.

Leonard Bailey, 29, “Pianoforte Maker,” and wife Elizabeth A. Wildes, 28, with their children, living at 30 Salem St. Winchester, in the 1855 Massachusetts State Census.

Most likely Leonard Bailey first saw a British dovetailed mitre plane used by another piano craftsman when he worked at the Bush & Lane Piano Case Manufactory in the early 1850s. Stewart Spiers, a planemaker from Ayr, Scotland, had exported a number of his dovetailed iron planes to the United States during the 1840s.

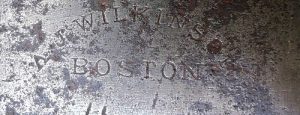

Circa 1840, in New York City, Lauritz Brandt, a Danish immigrant, began producing mitre planes, and bow drills for the piano industry. Seeing how expensive the British mitre planes were, through their custom made production costs, as well as the cost of shipping them to America, Brandt saw an opportunity in making these tools domestically. In the early 1840s, A.J. Wilkinson, an early mail order national hardware company based in Boston, bought in a number of Brandt mitre planes, and rebadged them with their proprietary stamp. By 1844, Brandt adopted the lever cap instead of a wedge for retaining the cutting iron, and soon thereafter, introduced the adjustable throat. Leonard Bailey would have observed some of the Brandt mitre planes brought to Boston by Wilkinson, as well as the later cast iron mitre planes made by George Thorested in the mid-1850s.

Having seen both the British mitre planes, as well as those by Brandt and Thorested from New York City, Bailey also saw an opportunity to supply piano case makers and high-end furniture makers with his own cast-iron mitre planes at a lower price point. So Leonard Bailey (1825-1905) started producing his mitre plane in the Spring of 1858, when he moved his from a small backyard workshop with dirt floor that he built at 30 Salem St., Winchester, a suburb 8 miles from Boston, to his own commercial workshop at 73 Haverhill St. in Boston.

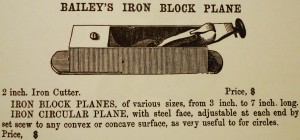

L. Bailey mitre plane, as advertised in A. J. Wilkinson & Co., Boston catalogue c 1867. Bailey’s mitre plane was also included in the earlier Bliven, Mead & Co. 1864 New York catalogue.

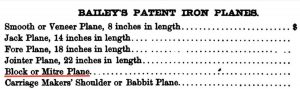

Bailey’s Patented iron planes, including his no. 9 Cabinetmakers’ Block plane, as offered in the Bliven & Mead Catalogue of 1864.

Wilkinson’s 1867 catalogue image was for a version 1, produced 1858.

Versions 1 (1858) and 2 (late 1858-c.1866)

The 1858 first version of Bailey’s mitre plane did not include the ‘broomstick’ handle, and appeared very much like the example pictured above, in the 1867 A.J. Wilkinson Hardware Catalogue, with Bailey’s cam- lock lever cap, patented 31 August, 1858. Bailey’s mitre included a depth adjustment for the iron based on Levi Sanford’s patent of 26 November, 1844. Version 1 and 2 used thick tapered cutting irons, such those by William Ash and Moulson Brothers in Sheffield, England. The adjustable mouth on the no. 9 was not patented.

Version 3 (1867-1868)

Bailey Mitre Plane, version 3, circa 1867-1869. Drawing by Ruben Morrison, from “The Gristmill,” MWTCA March 2000, p. 15.

Next significant innovations included the introduction of a thinner cutting iron (patented 24 December, 1867), and a new depth adjustment for the cutting iron (patented 6 August, 1867). The thinner iron, the 1867 yoke adjustment knob/screw, and a new bracket for the rear handle comprised the main improvements for version 3 of the Bailey mitre plane. This new iron bracket, was attached with screws from the inside of the heel of the plane into the thick cast iron bracket, which now had a rosewood ball handle instead of the broomstick. The top of this casting was machined, to mate with the plane iron. The depth adjustment lever was mounted on a pilaster which was an integral part of the inner casting of the heel of the plane body. With the increased accuracy and control over production tolerances, Bailey no longer needed assembly numbers for the various components during the period of production starting in 1867.

Version 4 (1869-c.1875>)

Stanley no. 9 Cabinet Maker’s block plane, version 4, circa 1870s, with horizontal adjustment knob, pat.’d. 6 August, 1867. Photo from MJD auctions, April, 2016.

Version 4 of the Bailey mitre, was produced in New Britain beginning in 1869 under ownership of Stanley Rule and Level Co., and supervision under Leonard Bailey; a few earlier version 4’s may have been produced in Boston, but I am not aware of any documented examples. Bailey mitre planes version 4 have an updated adjustable front sole piece, with a small raised rail on each side which slided fore and aft within 2 receiving grooves on either side of the plane body. Version 3 had the fitting of the front sole piece made adjustable laterally with two small shim-screws. The plate or ‘cap iron’ was now the familiar small oblong piece of sheet steel (instead of a larger, thinner rectangular sheet of steel–vers. 3) used on the later nos. 11, 11 1/2, 25, and 164 Stanley planes; it was attached to the cutter using the traditional cap iron screw. An oblong hole, oriented laterally, served to engage the nib on the depth adjustment lever. The pilaster inside the heel of the plane body, was now a separate vertical shaft attached with a single screw: this vertical shaft served to mount the adjustment lever. Bailey’s version 4 mitre plane was produced in New Britain in larger numbers, well into the 1870s.

Bailey’s 1858 and 1867 Patents etched on lever cap of a No 9, version 4, with horizontal adjustment knob (1870s). Photo from Jim Bode, 2023.

Stanley No. 9 plane, version 5, with vertical adjustment knob, and longer front and rear flanges, before circa 1900. Photo from antiquebuyer.com

Lie Nielsen’s No. 9 plane is longer, with a sole 10 7/8″ long, as compared with the 9″ long c. 1900 Stanley shown here. It’s also more massive, and looks to be more robust as compared with the original body casting, which can be prone to cracking at the rear, where the handle is attached. When the top fixing screw for the Stanley No. 9’s adjustable front sole piece is driven too tight, the casting can also crack on the sides, right above the adjustable front sole. While this example does not suffer from these problems, the Lie Neilsen is the one I go to first: it cuts wood very well, with no worries about breakage. It is, however, a rather big rig–14″ if you include the handle attachment–the user made handle is slightly oversized, in order to push the plane more easily.

N.E. Michel and his Piano Atlas (1945-1963)

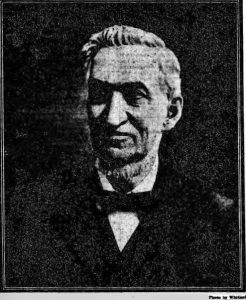

Norman E. Michel (5 September, 1894–23 December, 1972) did all of the early heavy lifting as far as the piano atlas was concerned. Norman was born in Pittsburgh, PA, and he ended his formal education after the 8th grade, which was reflected somewhat in his atlas. Michel was also a veteran of WWI. After the birth of Norman Jr. in 1920, Norman Michel moved out to Los Angeles to continue his long career as a Piano Salesman. Norman Jr. (d. 2008) graduated from USC in 1941, and went on to earn a PhD, spending his career in education. Norman Sr. undoubtedly instilled in his son the importance of education.

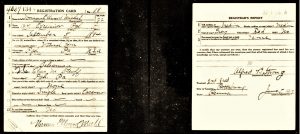

Norman E. Michel’s WWI Draft card, 5 June 1917. At 22, Norman was a Piano Salesman for Baltimore pianomaker, Charles M. Steiff.

During the late 1930s, Norman Michel began to compile piano makers’ serial numbers along with years of manufacture for the first edition of his Piano Atlas, which was published in 1947. Norman and his wife, Ruth, lived at 9123 Terradell Ave. in Whittier, Los Angeles, California at the time of the 1950 U.S Census.

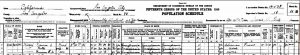

Norman E. Michel, his wife Ruth, and son Norman Jr., were living at 382 Third Ave. in Los Angeles at the time of the 1930 U.S. Census. Norman Michel was a Piano Salesman.

By 1950, Norman Michel had quit his job as a piano salesman, and was a self-employed publisher, working 60 hours a week, compiling his Piano Atlas. 1950 U.S. Census.

From David Crombie’s “World Piano News:”

In the late 1940s, Bob Pierce worked at Penny Osley Music in Los Angeles and in 1947 he and Norman Michel produced the first Piano Atlas. The work was a great success, and subsequent editions were published. Unfortunately, in 1963, poor health forced early retirement on Norman Michel, and Bob Pierce took over sole ownership of the atlas.

1950 MIchel Atlas order form, showing international focus. From “The Piano Technician,” October, 1949.

David Crombie most likely received his information for this article in his website from Larry Ashley, present owner of the Pierce Piano Atlas, and son of Bob Pierce. Unfortunately, Norman Michel’s role in authoring and publishing the Michel Piano Atlas was minimized. From early on, Norman Michel made an effort to cover piano manufacturers internationally in his Atlas: including Kawai and Yamaha in Japan, as well as the European piano makers, both major–like Schimmel, and minor–like August Forster.

Bob Pierce’s early involvement with the Michel Piano Atlas may have been exaggerated. I have the 1949, 1957, and 1961 editions of the Michel Piano Atlas, and in all these editions there was no mention of Bob Pierce, nor was he listed as a co-publisher. The 6th edition of Michel’s Piano Atlas, was published in 1965, and this was the first time that Bob Pierce was documented as publisher. For those of you who are familiar with the later Pierce Piano Atlases, you will know that Bob Pierce was not a wallflower. On the contrary, Pierce included himself in many of the photographs within the Piano Atlas, alongside various pianos as well as looking towards the camera on many of his traveling vacations.

Norman Michel continued to work on his compilations after 1963, and in 1969, he published his organ atlas, which featured reed organs, harmoniums, and melodions. Robert F. Gellerman (1928-2011) later published two editions of his “International Reed Organ Atlas;” the 2nd edition was published in 1998. Gellerman’s Atlases were largely based on Michel’s pioneering research. The same can be said regarding the Pierce Piano Atlas.

Here is a bookseller’s description of the 1957 edition:

Mr. Michel painstakingly produced this epic directory back in the ‘fifties, and it is a testament to his dedication and diligence in listing all the manufacturers data—down to the serial numbers. The ’57 edition contains more obsolete stuff than the expanded 1961 version, making it perhaps even more notable to the collector and the piano historian. This copy is complete with Michel’s cover letter to schools and teachers laid in.

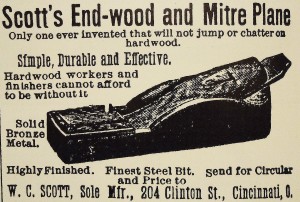

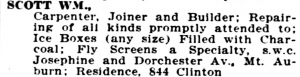

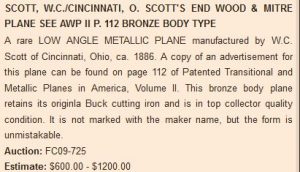

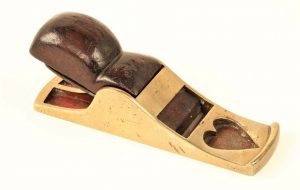

William G. Scott, Planemaker

This Scott mitre plane was made at 204 Clinton St., Cincinnati, Ohio, with German silver shield or crest inlaid into the rosewood front infill. Apparently, there were at least three sizes of this plane; this one is 9″ long, with a 2″ L.& I. J. White iron. Others were 8 5/8″ with a 1 3/4″ iron, or 8″ long with a 1 5/8″ iron.

A feature universal to all Scott mitre planes were the streamlined lugs along the inside of the cheeks, utilized for retaining the wedge and iron instead of a bridge.

William G. Scott’s mitre, to my knowledge, was the only production infill mitre plane made in 19th century U.S.A. outside of New York state. Like the New York makers of pianomaker’s planes, Scott found his inspiration from the infill planemakers of Great Britain. Unlike the New York makers, Scott was influenced by profiles with more fluid lines, rather than straightforward box mitre designs. The smaller versions of this plane resemble an oversized Irish chariot plane. Scott’s parents were born in Scotland, so chances that William Jr. did not know about this Scottish/Irish style of planemaking would have been close to zero. Especially considering his surname. In the relatively small number of these planes that have surfaced, there is much variation; Scott’s casting designs were constantly tweaked and changed. Its fairly obvious that William Scott enjoyed playing around with his designs, because for usefulness and practicality reasons, it certainly was not necessary.

Using a combination of British and American made cutting irons irons in his planes, Scott typically bought in W. Butcher and Moulson Brothers irons from Sheffield, and D.R. Barton, of Rochester, Buck Brothers, of Rochester, and L. & I. J. White, of Buffalo irons for his mitre planes.

Scott mitre plane. It’s the same as the example in the advertisement with the exception that the two infills were affixed to the casting with machine screws. It’s small: 8″ long, with a 1 5/8″ Moulson iron.

“Sole Manufacturer,” could be taken literally: Scott likely worked alone, after business hours, in his home-based workshop. Its true that Scott mitres are rare, but the small and steady amount of them that surface over the years, indicate that Scott must have continued with his planemaking endeavors through a long timespan. This would also be supported by his use of many casting variations which would have been used for a good number of casting batches over time.

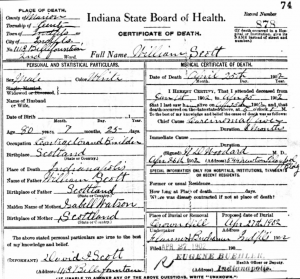

Some Scott Family History

At 17, William George was a Carpenter’s Apprentice. William Scott Sr., Jr., Eliza, and family, 415 S. Tennessee St., Indianapolis, Indiana. 1870 U.S. Census.

William George Scott was born in Hamilton, Ontario 5 May, 1851, and raised by William Scott Sr. (1822-1902), a prominent Carpenter/Builder, and his wife Eliza Payne (1823-1896). William Sr and Eliza had emigrated from Scotland in around 1849. It was likely that William Sr. brought a Scottish mitre plane (along with other tools) with him when he left the old country; this would have provided William George an example from which he could derive his own work. The Scott family remained in Hamilton Ontario for 10 years.

There is a discrepancy in the records regarding country of origin for William Sr. and Eliza. In his 1870, 1880, and 1900 U.S. census entries, William Sr. conveyed to the census taker that Scotland was the country of origin for himself and Eliza, as well as their first-born child, Jennie (b. 1847-8). But in the 1880, 1900, and the 1910 U.S. Censuses, William Jr. reported his father as born in England and his mother as born in Ireland.

There may have been some unfinished business between William Sr. and William Jr., not only because of the differing accounts around country of origin , but also because William George was not mentioned in William Sr.’s obituary:

Indianapolis Journal 26 Apr 1902 p. 3

“William Scott, after an illness of several weeks, died at 5 o’clock yesterday afternoon at his residence, 1113 Bellefontaine Street. Mr. Scott was 80 years of age. He was a native of Scotland. Coming to America with his wife, whom he survived by 6 years, he first located in Canada, but removed to Lafayette, IN and soon afterward came to this city where he had resided for the last 40 years. He was one of the oldest builders and contractors and continued in business until a few months ago. His sturdy character and thoroughness were evidence in all his work, even in the rush and boom years of the early [18]70’s when he was very actively engaged. Mr. Scott was a member of the First Presbyterian Church and was a thorough-going Scotch Presbyterian. He leaves a family of 7 children. They are David I. and Walter P. contractors; John with George J. Mayer and Co.; Misses Elizabeth and Belle W. and Hattie of this city and Mrs. Lee Williamson of Terre Haute. Mr. Scott was identified with many benevolences and in former years was associated with the late Father Bessonies and John G. Blake in acts of charity. He was one of the builders of the Sixth Presbyterian Church on the South Side. He was a member of the Masonic fraternity. He was a lifelong Republican and had much to do with the upbuilding of the party in this city and state in the earlier years of that political organization.”

In the 1870 U.S. Census, William Scott Sr. had 8 children, not 7.

In 1859, William Sr. and his family immigrated to the United States and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana. Promptly after arriving, William Sr. started carpentry work to support his large family. Notably, the Scott family owned their house in 1870, so William Sr. was quite successful as a Carpenter/Builder, obviously profiting handsomely from the rapid growth of Indianapolis at that time.

The Scott family lived at 415 South Tennessee St. (Capitol Ave. after 1894) for at least 10 years, starting in 1865. 1865 Indianapolis City Directory.

William G. Scott Jr., Carpenter 408 6th St., Detroit, Michigan, as recorded in the Detroit City Directory for 1874. At 22, Scott was out on his own, living in another city.

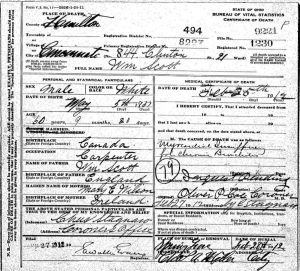

After William Jr.’s apprenticeship in carpentry in the mid to late 1860s (presumably with his father), he moved to Detroit, Michigan, where he worked as a carpenter. In the 1870s, William George courted Susannah Julia Gettiss (1846-1937), originally from Toronto (and whose father was born in Paris, France). William and Susannah married on 9 October, 1878 in Detroit, Michigan.

Shortly after marrying, the young couple moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, but they only remained there for 2 to 3 years, as William George and Susannah moved again to 204 Clinton St. in Cincinnati in 1881.

William Scott, carpenter. Cincinnati City Directory, 1882. First year of entry for Wm. Scott in Cincinnati.

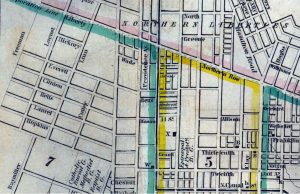

1845 Cincinnati street map, showing a portion of the West End, including Clinton St. Liberty and Linn Streets are still there.

Clinton Street was in the West End, near the new Taft Information Technology High School on Ezzard Charles Drive. During the 1950s, the historic West End was razed for ‘urban renewal.’

William and Susannah and their family lived on Clinton St. for the duration of William’s life. Between 1881 and 1895, the Scotts lived at 204 Clinton St.; in 1895, their address changed to 844 Clinton St. This was either a very short move, or a renumbering of Clinton St. I suspect Clinton St. was renumbered because in some years, both nos. 204 and 844 were marked “rear” in city directories.

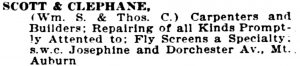

In 1905, Scott entered a short-lived partnership with Thomas C. Clephane. 1906 Cincinnati City Directory.

Southwest Corner of Dorchester Ave. and Josephine St., Mount Auburn, Cincinnati, Ohio. William G. Scott listed this location as his workshop from 1900 to 1909. The present house was built in 1916. Photo from Google Maps.

In 1910, William G. Scott, 58, was still living at 844 Clinton St. with his wife Susannah, and 3 adult children: Grace R., William B., and Arthur T. Scott was a self employed carpenter who built houses, amongst other things; he was also an employer. William and Susannah rented 844 Clinton St.

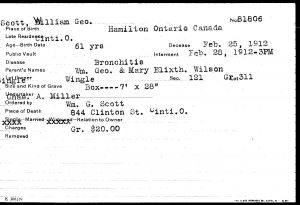

Even in death, there was a discrepancy around the countries of birth for William George’s parents. Here we have William Scott Sr. (1822-1902) given as William George’s father (as expected) and a Mary E. Wilson (b. Ireland) as his mother. Again, the father was listed as born in England, not Scotland.

William’s widow, Susannah J. Gettiss (1846-1937) would go on to outlive him by 25 years.

Interment card for William G. Scott at Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio. Courtesy of Tom Perdiew.

Complicating matters further, William George and Mary Elizabeth Wilson were listed as William G. Scott’s father and mother. I have not seen documents for William Scott (1822-1902) where he possessed any middle name, let alone George. I am now inclined to think that William G. Scott was given away for adoption from the Wilsons to William Scott and his wife Eliza Payne, resulting in his surname change.

One Mary E. Wilson died on on 31 August, 1853, and was buried at the Trinity United Church Cemetery in Hannon, Hamilton Municipality, in Ontario, Canada. This may have been William George’s mother.

Burial site (flag) of William G. Scott in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. One of many craft workers who was interred without a marker. Photo courtesy of Tom Purdiew.

Sometimes the efforts to keep a tool working prove interesting enough to elevate the selling price of a tool. This repaired Scott mitre plane sold for $450.

Scott mitre plane with L. & I. J. White iron, 8″ long. Similar to the plane shown above, but with some differences in the lines of the casting. Photo from Martin Donnelly Auctions, c. 2002.

Martin Donnelly’s flowery description of this plane. 2002.

The nose on this plane is rounder than any of the other Scott castings shown here, and the iron appears to be set a few degrees lower than the others as well. It was sold in the 46th Brown tool auction in March 2015. Plane is stamped by ‘C. Fielding’ in a wave pattern. Some of you may notice that the signed Gabriel mitre no. 220 shown on the next page (Early English Mitre Planes) was also stamped by C. Fielding. It is fairly common that when a collector passes away, the heirs place the tools up for auction to be returned to the collecting community.

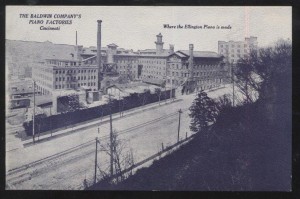

Baldwin Piano Factory, c 1920. While the introduction of Scott’s mitre plane predated the introduction of Baldwin pianos by at least four years (1890), chances were good that a few Scott mitres were used therein.

Largest Scott mitre plane with 2″ iron and smallest with 1 5/8″ iron. Bodies are similar, but the front of the smaller one has sharp corners, and the large one has rounded corners.

By 1886, D. H. Baldwin’s potential work force of skilled craftspeople was already established in the Cincinnati area, and besides, Baldwin was not the first pianomaker in southern Ohio. Frank Renfrow, a longtime piano specialist in the Cincinnati area, documented the following local pianomakers from 1825 to 1880: Charters, Garish, Golden, Reuss, Strange, Clark, Bourne, Smith & Nixon, Blackburn, Britting, Dannrechtin, Schaunel, Wardrogen, and Chase, among others.

Scott mitre plane, from the John G. Wells collection. John Wells was a prominent architect (and tool collector/researcher) from Berkeley, CA. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, February 1, 2019.

W.G. Scott Mitre Plane, left side, with ornate two-toned front infill in contrasting rosewood and maple.

For William G. Scott, making these mitre planes was truly a labor of love; in this line-up, and indeed all of the Scott examples shown here, no two castings were the same, and the woodwork was always different. At the very least, he had a large degree of control over his castings. And it’s not outside the realm of possibility that Scott did his own lost wax casting in bronze. While not the most innovative planes of the late 19th century, Scott mitre planes hold a creative and unique place in the history of American planemaking.

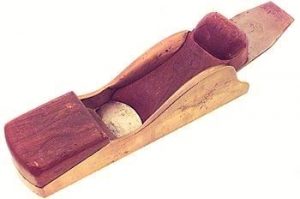

IRISH CHARIOT PLANE

The roots of William G. Scott’s mitre plane designs originated from the Scottish mitre plane, which was a somewhat ephemeral form, and not made in quantity. Scottish mitre planes emerged in the mid to late 19th century, and lasted until the 1920s. Another derivation from the Scottish mitre was the Irish chariot plane, which was a slightly smaller version of the Scottish mitre, with a typical 1 3/4″ iron and a length ranging from 6 1/2″ to 9″. Irish chariot planes were also a stretched version of the classic English chariot plane, a blocky form ranging from 3 1/2″ to 5″. Others just consider Irish chariots as another variation on a block plane. All of these assertions are true. The vast majority of Irish chariot planes were unmarked, and user made–perhaps in a small casting batch for members of a workshop, or a group of friends.

Unmarked quality Irish/Scottish chariot plane, with cupid’s bow on wedge. The iron is set at 17 degrees and is 1 3/4″ wide at the mouth. Rosewood was used to bed the cutter. Its an example of the creativity many craftworkers possessed in the late 19th century. Traces of Scottish mitres, English chariots, and block planes are all apparent in its design.

Another example of this plane in iron was sold in the December 2016 D. Stanley Auction, lot 742.

Irish/Scottish Chariot Plane. Formerly from collection of Max Ott. Photo from Donnelly Auctions, May, 2021.

This Irish/Scottish Chariot plane, also in gunmetal and ebony, is very similar to the Chariot plane shown above. Max Ott, a noted London cabinetmaker and collector, thought enough of it to add one to his collection.

Another version of the Irish Chariot plane. This design, with stepped toe and narrow ‘ears,’ can be observed in other examples. Some of these Irish Chariot planes were so similar as to probably be from the same casting pattern.

This Irish Chariot plane (below left) was made to the classic design pattern, with a knob-shaped wedge, swept sides, and divided recesses front and back, in red.

Irish chariot planes with a heart were a thing, but not a big thing. This was a true folk art.

Irish Chariot Plane, sold by William McQuaid McMaster (1871-1931), 24-26 Church Lane, Belfast. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auction, October, 2021.

The following photos of another example of the McMaster Irish Chariot plane came from www.oldhandtools.co.uk

As many as a third of all chariot planes made were of the ‘Irish chariot’ type. Of all the infill planes, the Irish chariot was one of the most free in form, and at any given time, a variety of designs are available for sale on ebay U.K. The Irish chariot plane shown below has features that reference improved mitre planes, Norris No. 32 Thumb planes, along with the swept cheeks of an Irish chariot. This was a craftsman made plane, by one E. (Edward?) Edwards. There were half a dozen cabinetmakers with the name Edward Edwards, who were born in the U.K. between 1850 and 1880.

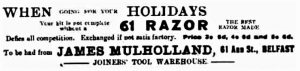

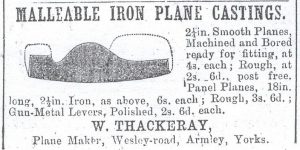

Unfortunately, the quality on many of the Irish Chariot planes offered for sale varies as well, with a majority being average at best, with a few of good quality. At least three established makers made Irish chariot planes: James Mulholland of Belfast, Edward Preston of Birmingham, and John William Thackeray of Armley, Leeds. All of them could be considered at the high end for fit and finish. Thackeray classified his Irish chariot plane as “The Ivy,” Improved Mitre Plane, but all of the design characteristics point to the former.

James Mulholland:

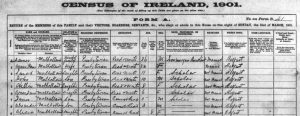

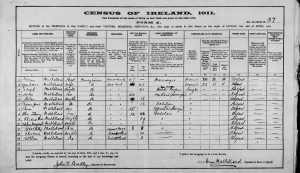

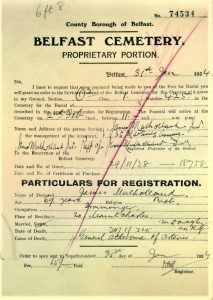

James Mulholland was born in Belfast, on 30 April, 1864 to John Mulholland (1844-1919) and Ellen McCabe (1843-1894). James married Agnes Jane Rea (1868-1944) on 2 April, 1888 at Fort William Pa Presbyterian Church, in Belfast.

Irish Chariot planes first appeared in the 1890s, and they continued to be made into the 1930s. Were they actually developed in Ireland? If James Mulholland made Irish chariots in the 1890s, then there’s a good chance that it was the case. A James Mulholland, “Ironmonger,” was listed in the 1890 and 1900 P.O. Directories for Belfast. Throughout the 1890s, there were various listings for a James Mulholland as a joiner, carpenter, or smith. Perhaps these entries were of an older family relative of ‘our’ James Mulholland, whose father, John Mulholland, was born in 1844, and died in 1919. James Mulholland was located at 61 Ann Street in Belfast from 1907 to 1932, and this address was stamped on some of his Irish chariot planes. Like Preston, Mulholland’s version was also orange/red, with a plain toe, like Preston version 1, but with swept sides like Preston version 2.

What is clear, is that the Irish chariot pattern was not a London design. All of the known makers were north of London.

James Mulholland, Belfast, and Edward Preston, Birmingham, Irish chariot planes. Photo by George Anderson.

James Mulholland, “Ironmonger and tool dealer.” 61 Ann St., Belfast. First year with telephone in 1908.

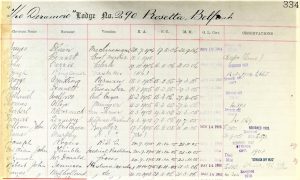

James Mulholland and Robert John Dennison, Hardware Merchants, joined The Deramore Lodge, at 290 Rosetta, Belfast, on 14 May, 1906.

Was Mulholland first to make Irish chariot planes?

–Only if a Mulholland plane is found without the 61 Ann St. address stamped on it. 1907 was the first year for Mullholland at 61 Ann Street, Belfast. In their 1901 catalogue, Preston included their Irish Chariot plane.

Mulholland’s shop was a family business: son John Mulholland, 20, was an assistant ironmonger, Sarah, 21, was the book keeper, and James Jr., 15, was an ironmonger’s apprentice.

Robert Kelly Mullholland was managing a tool and hardware store in Kent, England in 1939.

Alexander was a model engineer in the tool making field during 1939. This kind of training would indicate that the design of some of the Mulholland tools could have been done in-house, and that the moulds and cores could have been retained in-house as well.

James Mulholland must have carried a fair amount of elegant spirit levels, as they do turn up in the market on occasion.

I held back on publishing this photo for some time because this is not a happy one; it has the signs of a funeral, all too common later in life.

Mulholland’s Irish Chariot plane was 9 1/4″ long, 1/4″ longer than the late Preston Irish Chariot plane.

Mulholland Chariot plane throat insert. Photo by Roy McBride, 2010.

The Mulholland plane pictured above is so clean that it is almost impossible to spot the tightly fitting throat closer. In this example, there is more contrast between the iron body and the steel plate.

My Mulholland Irish Chariot plane has an iron that is marked W. Marples.

1932 was Mulholland’s last year of entry in Kelly’s Belfast Post Office Directory at 61 Ann St. James Mulholland age 69, died on 30 January, 1934, and was buried in Belfast City Cemetery. Effects £2215 6s 7d.

Mulholland Irish chariot plane–work on the teak hatch of a yacht. Photo from CKD boats, 2012.

Edward Preston:

Preston’s Irish chariot plane first appeared in his 1901 catalogue; it is unclear how long it was made before that, however. The cutting angle on version one is noticeably higher than the second version.

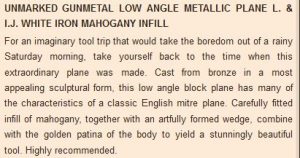

Preston’s Irish chariot plane was also available in gunmetal, and with a rosewood or ebony wedge. There was no infill.

In their 1909 catalogue, Preston continued to offer their 7 1/2″ Irish Chariot plane with throat closing plate. Prices remained the same as 1901.

Preston Irish Chariot plane,version 2. Length is 9″, 1 3/4″ iron, embossed “PRESTON,” and no throat closer. The earliest examples of this model had a screwed on throat closer.

Both Preston Irish chariot planes had a knob shaped wedge.

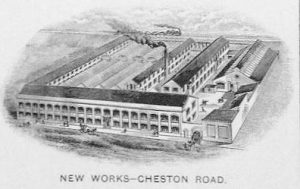

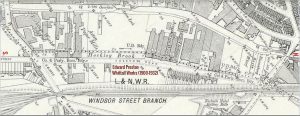

Sometime early in the production of the second larger version of the Irish chariot plane (c. 1914), casting technology had advanced to the point where a mouth closer was not necessary to achieve a fairly fine mouth. Having said that, my version 1 Preston Irish chariot has a tighter mouth (<1/16″) than this version two example at 3/32″. Preston Irish chariot planes were made in the New Works at Cheston Road, Aston.

Preston No. 1364 Irish Chariot Plane. Early version 2, with throat plate. Photo from Andrew J. Stevens, Toolbazaar.co.uk

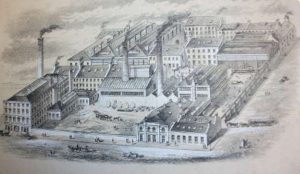

Invariably, all captains of industry asked their hired artists to make the most impressive image possible of their manufactories. Edward Preston Jr. (1835-1913) was no exception. At the factory’s peak before WWI, Preston employed about 200 men and women.

During the first half of the 20th century, the narrow piece of land between Cheston Rd. and the rail line was developed considerably.

“Manufacturer Rules, Planes, Spirit Levels and general tools in wood, ivory, steel, iron, and brass.”

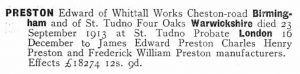

This will index listing put Edward Preston Sr.’s (b. 1798) death on 14 April 1875. Most publications have his death in 1883.

It was Edward Preston Jr. who was responsible for expanding his father’s business beyond wooden planes, first adding rules, and eventually offering a full line of tools.

The first version of the early type had 90 degree notches at the sides of the nose, as shown in the Preston 1901 catalogue. Subsequent copies of the later Irish Chariot plane did not have the faux screw countersinks in the toe. Some of the last Preston Irish Chariot planes were not cast as carefully, and definition was diminished in the lettering, and in the casting generally. It was still a good plane.

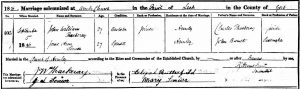

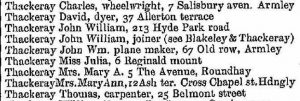

John William Thackeray:

“The Ivy Improved Mitre Plane [Irish chariot plane] with fine Eye,” made by John William Thackeray, circa 1894 to 1930. 1922 Catalogue. 7 1/2″ long, 1 3/4″ iron. From Thackerayplanes.com

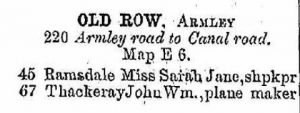

John William Thackeray was born 10 April, 1869 in Burnt Yates, Clint, Yorkshire, to Charles and Sarah Thackeray; Charles was a joiner and farmer in 1871. “The Ivy” improved mitre plane (Irish chariot) was Thackeray’s best known plane, and the only one that had this mark on the body. It was named for the Ivy Works, at 51 Old Row, Armley, Leeds, where the plane casting was finished off. Occasionally, Thackeray’s planes would be stamped with a large “T” on the body.

Prices in the 1922 catalogue. Castings only: Nickel plated, 11/6; Malleable Iron, 9/6; Gunmetal, 11/6. Rosewood or ebony wedge 9d; Thackeray iron 1/6.

Improved mitre shooting plane was actually a simplified version of “The Ivy” without the embossed toe and the throat closer. All of Thackeray’s planes were available as separate components: body castings, irons, infills, wedges, and lever caps, were all available individually. For those who had skills and sought to save money, this could have been a boon. For those who chose to buy a completed plane–that could add up.

Prices in the 1922 catalogue: Nickel plated, 9/6; Malleable iron, 6/6; Gunmetal, 8/; Steel-faced gunmetal, 10/. Rosewood or ebony wedge 9d; Thackeray iron 1/6.

This example differs from the catalogue drawing by including a heraldic shield on the nose, and a concave lozenge shape on the bridge. It has a mahogany wedge, and is nickel plated. The Thackeray iron is set at a low 14 degrees, and the mouth shows no chips or cracks, which is as much a complement to the original user as it is to Thackeray, as the iron is fairly short.

Shown below is another Thackeray Irish Chariot plane, standard model, in gunmetal, with five pieces of rosewood: four infills and wedge.

Charles Thackeray “Joiner (Master), and Farmer, 46 1/2 acres.”

Charles Thackeray, Charles Jr., and John William, 22, were all listed as “Joiner[s]” in 1891.

Jane Anne Senior (1869-1904)

John W. Thackeray, was listed as a “Carpenter; Employer,” with wife Jane A. and son Fred, 3.

Thackeray rented his property.

John William Thackeray married his second wife, Annie Elizabeth Stead (1866-1916) in North Bierley, Yorkshire, in the late Summer of 1909.

Thackeray’s version of an Irish chariot plane was heavier than other examples, as seen in the depth and thickness of the casting. That does not make it a mitre plane. The bed was infilled with rosewood, and the Thackeray iron was marked on the underside.

“The Ivy” embossed casting was part of a general practice by several planemakers to promote their products around the WWI era. Preston was doing it, then Spiers introduced their embossed lever cap. A few years later, even Stanley made a name embossed lever cap.

Price for a completed “The Ivy” plane was 13/9 for either the nickel plated or the gunmetal version in the 1922 catalogue. Preston’s price for the iron Irish chariot was 10/- and gunmetal 14/- in the 1901 catalogue. There was a good amount of inflation between 1901 and 1922, so Thackeray was less expensive.

Thackeray “The Ivy” in gunmetal (below), which was sold in the David Stanley September, 2022 auction:

Photo from corner of Canal Road and Old Row. The Asbestos factory was directly behind Old Row, now Ledgard Way. Photo from leodis.net

Aerial view of Old Row from 1949, showing general location of Thackeray, and the J.W. Roberts asbestos factory behind. Photo from morningstaronline.co.uk

All of the white stuff was piles of asbestos fibres blanketing the neighborhood. Many locals contracted mesothelioma. J. W. Roberts was producing asbestos there from 1906 until 1959.

Some urban renewal is apparent on both sides of Ledgard Way (Old Row).

John William Thackeray addresses: 5 Wesley Place, Armley <1891-1893>; 5 Elizabeth St. c. 1901; 67 Old Row 1907-1912; 51 Old Row, “Ivy Works” c. WWI ~1930.

This map was drawn before J.W. Roberts Asbestos factory was built.

Two foundries and a forge were minutes away from Old Row. Price competition between these foundries likely made it viable for Thackeray to sell unfinished plane castings profitably. Like other planemakers, Thackeray would have owned his proprietary moulds and cores, bringing them to the foundry when a new batch was required.

Thackeray castings available to the trade. From “The Illustrated Carpenter & Builder,” 16th March 1894.

In 1893, five individuals were listed on Old Row. There must have been a lot of empty units in and around Old Row.

By 1908, John William’s father, Charles was working as a wheelwright. No doubt, most, if not all these Thackerays were related.

John William Thackeray wore three hats: joiner, planemaker, and undertaker. 1908 Leeds P.O. Directory.

It must have been interesting… There has always been a market for finely made caskets.

From the beginning of his planemaking career, John William Thackeray offered an a la carte menu for his customers.

By 1900, John William Thackeray was offering a full line of planes. As early as 1894, Thackeray had a catalogue which included his line of iron and gunmetal planes.

Given the health risks around Old Row, it’s reassuring to know that John William Thackeray lived a full lifespan.

Two months previous to John William Thackeray’s death was the Leeds blitz of 14/15 March 1941. Armley was particularly hard hit. It was a stressful time to live and work there.

For a man who had three jobs, Thackeray made a good amount of planes. He must have worked hard.

Omitting the throat plate insert allowed Thackeray to move the mouth closer to the toe, and to lower the overall angle of the iron from 22 degrees to 14 degrees.

Norris

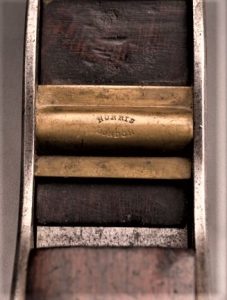

Norris mitre/chariot plane, no.1270 in David Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools.” Photo from Jim Bode, 2019.

Only two of these planes are known. It is 6 3/4″ long x 2 1/2″ wide, with a 2″ iron, bedded at 19 degrees. All parts were marked with a “0”. The mouth was formed using a front sole plate. In addition to the Norris stamp, the casting was marked “Patent Metal.” It has a flat heel like that found on Scottish chariot/thumb planes.

Norris mitre/chariot plane, no.1270 in David Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools.” Photo from Jim Bode, 2019.

A FEW BENCH PLANES

Norris A1 panel plane with 1922 patent adjuster. Design closely follows that of a Spiers no. 1 panel plane, but with an added lateral and depth blade adjusting mechanism.

Below are four smoothing planes. Top row shows a Norris no. 3 parallel sided smoother with mahogany infills, and built in the 1930s. Next to it is an equivalent Spiers parallel smoother with mahogany infill, also made in the 1930s. Quality in the Norris shop during the 1930s exceeded that of the Spiers Paisley shop in the 1930s, but the Spiers is still a workable tool. Bottom row shows an unhandled Spiers coffin smoother circa 1870s and 1880s. Next to it is an early 20th century Norris parallel smoother, no. 3. Similarity of designs from these two makers exemplifies the great extent to which Thomas Norris ‘borrowed’ from Stewart Spiers for his entire product line-up (with the exception of some cast iron bench plane models).

Craftsmen would sharpen several plane irons, in a single session, for each plane every day. By doing so, workers would not have to interrupt their work flow at inopportune moments, and would instead enable consistent optimal production. Because of that, all four smoothers have replacement irons and would be considered user planes rather than collector’s items.

Mathieson Infill Planes

Mathieson was a major tool manufacturing business in Glasgow, Scotland, with production and overall business philosophy set up for large scale operations. In the mid 19th century, Mathieson was a growing maker of wooden planes, and in the 1860s, began to make their own cast iron blades and other edge tools. At this early point, customer demand for cabinetmakers’ steel infill planes was limited, and did not warrant establishing their own in-house boutique production line. So Mathieson bought in planes from other manufacturers.

From the mid to late 19th century, Mathieson bought in their metal planes from Stewart Spiers. Many of these Mathieson/Spiers planes are more or less identical to Spiers marked planes with the exception of the early and rare series of Mathieson planes with rounded infills (possibly infilled at Mathieson’s factory), some rare cast planes, including an early cast improved mitre plane, and the early Mathieson Thumb plane with the crest in the cheeks center weighted. There are other exceptions.

Shown below is a very early c. 1840s Spiers mitre plane that has been rebadged as Mathieson Edinburgh. This plane was photographed in the Thomson Roddick Callan Auction of November, 2022.

After Spiers, Mathieson began to purchase their planes from Thomas Norris in around the year 1899.

“STEEL” stamps on Mathieson (Norris) planes: left, STEEL with serifs c. ~1899-1905; middle, STEEL in plain letters c. ~1905-1910; right, STEEL in italicized letters c. ~1910-1940.

Although some collectors (whom I respect) believe that the Mathieson planes with the STEEL stamp on the toe, and Sun/Moon stamp on the lever cap were made in-house by Mathieson, or in some opinions, by another third-party planemaker, I do not think that Mathieson was ever an infill plane maker. Mathieson planes, circa 1910 to 1940, continued to show Norris characteristics and details, even after the switch to the STEEL stamp, and the addition of the stamp on the lever cap. Considering Mathieson’s preference for economies of scale, they decided to remain producing their proven products in great quantities: i.e., wooden planes, plane irons, and general woodworking and trade tools.

Early English mitre plane.

This mitre plane showed evidence of having been in the USA from the 1860s or 1870s. The Barber iron dated from that time, and it looked like the rosewood wedge was made for the replaced Barber, Auburn, N.Y. iron in that time frame. The rear infill bed was converted to adjustable by fitting a captive bolt into a mortise on the bottom side of the infill. Inspiration for the alteration–19th century hardware was used–likely came from a period craftsperson who was envious of the new adjustable N.Y. mitre planes, and made his own mitre adjustable as well. The front infill on this example had very early features, such as the lack of a moulding at the back, and having been made of beech.

I consigned this plane to an auction, and it sold to a collector who approached it as a project plane. He removed the front and rear infills, and started to make a new infill bed. Then he died. The project plane, now shined up, was again consigned to auction without a front infill. I did not bid.

Split Scroll and rounded nib

Split scroll and rounded nib on 19th century mitre plane. Photo from Reeman Dansie Auctions, U.K., in 2018.

The rounded nib was a variation on the standard trapezoid shaped nib, and quite rare. When the streamlined nib (or sneck) was used, it was primarily confined to Scotland. James Hay of Edinburgh used this in the 1840s, and Stewart Spiers of Ayr made a few in the ~1850 to <1870 period.

Unmarked, circa 1845 Mitre plane, with sneck cut-outs, and rolled nib. Photo from oldtools.co.uk, 2014.

Moisset Plane Photos below by David Stanley Auctions, 2019:

“The famous “MOISSET” plane originally offered in the Arnold & Walker catalogue No 4 in 1976 for £775 with this description;Lot 253 Boxwood plane which formed part of the Moisset collection, recently dispersed at auction in Versailles (the January issue of the Argus des Antiquities reported on the sale with a picture of this plane) It measures 4″ x 1 1/2″ and is constructed of deep coloured boxwood with an ebony sole insert, these richly decorated planes are an intriguing phenomenon, it is hard to imagine that they were the day to day tools of working tradesmen, particularly when the sole, the wearing part, is elaborately inlaid, as it is on other examples. Yet some, such as a long plane in a private collection in New York and one in the Science Museum in London, show signs of prolonged wear. Our plane has been repaired at different periods, the wedge appears never to have been finished off as the lower edge blocks the mouth. There is a plane in the Art Institute of Chicago which has several closely similar features. The Sunday Times Magazine, May 16th 1976 illustrates this plane.Roger Phillips purchased this plane from the Arnold & Walker catalogue, amongst hundreds of other planes he bought in England in the early days, all these tools were shipped back to California, and because he was so busy running his shop-fitting business, most of these parcels remained in his warehouse unopened for many years. In the early 90’s, after he had semi retired, Roger invited me over to help him open these parcels and sort out what he wanted to keep and what he wanted to return to England to sell. An auctioneers dream. Sorting through these parcels I came across this Moisset plane, Roger had obviously forgotten all about it, I slipped it into my pocket without Roger noticing and back at the house I gave it to Eleanore to give to Roger for Christmas, apparently the best Christmas present he had ever received. The plane has since passed through the Dave Englund collection to the John and Janet Wells collection G++”

D. Stanley Feb 2019