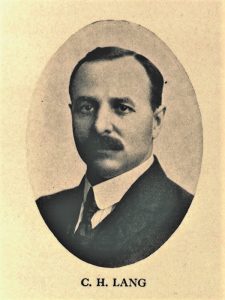

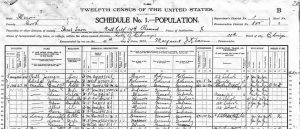

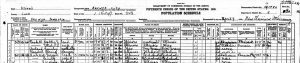

Carl Herman Lang, in the 1900 U.S. Census: “Tool and Die Manufacturer,” living at 27 South 4th Avenue, Chicago.

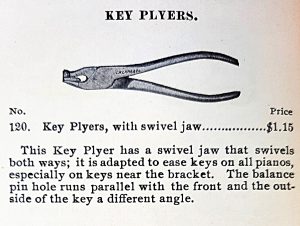

Carl Herman Lang was born 30 Dec 1868, in Erlabrunn, Erzgebirgskreis, Sachsen, Germany. Erlabrunn was 35 miles northeast of the famous instrument making town of Markneukirchen. Lang immigrated to Chicago, in the United States in 1890. Shortly after arriving, he founded the C. H. Lang Co., which was a small hand tool making facility for the piano industry. Lang was a machinist and inventor, but he is mostly remembered as the first Harley Davidson motorcycle dealer, c. 1905, and he also held motorcycle patents, along with several piano tool patents. This company made a full line of piano tools.

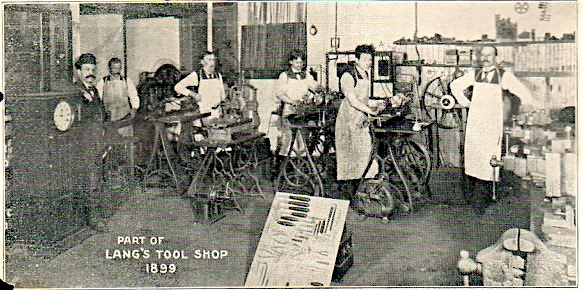

Lang is posing with the work crew in in his shop. The poster in the foreground was drawn by Lang and shows many of his tools. This poster, reduced and included in the 1905 catalog, reveals that most all of Lang’s piano tools had reached their mature and final form by the end of the 1890s. Manually powered equipment predominates in this 1899 photo, although an electric motor is driving one machine, just to the left of the poster.

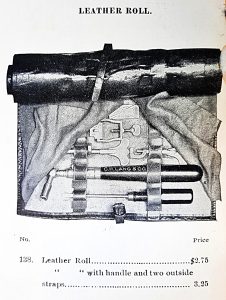

Thanks to David Abdalian, RPT, for generously lending me the 1905 Lang catalog, the 1917 and 1926 Lyon and Healy catalogs, and excerpts from the 1934 Tonk Bros. catalog. Now I can begin to fill in some missing information regarding Lang, and Lyon and Healy, who bought out Lang in 1914.

This 1899 photo of C. H. Lang’s shop showed six men, and a 1940s photo of the Hale/Tuners Supply toolshop also depicted six workers. It would be fair to assume that in both cases, the entire toolmaking staff was shown. Both Julius Erlandsen and Joseph Popping had six men laboring in their shops during 1897, as recorded by the “Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of the State of New York.” Six seemed to be the magic number for these small piano tool makers.

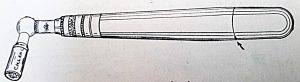

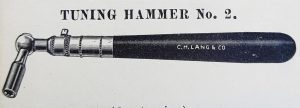

Lang tuning hammer no. 2, with C. H. Lang engraved twice, and detailing on the steel ferrule. The handle is made of ebonite (vulcanite), which is a natural rubber hardened by a process with sulfur.

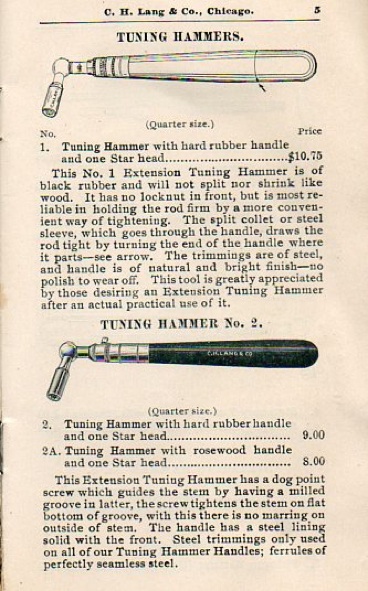

The $10.75 Lang hammer no. 1, also ebonite; adjustable shaft is friction-fit within the internal tube, shown in the left photo. There is no set screw as in the first example.

Ornate ferrule on Lang No. 1 Tuning Hammer, and grooved extension shaft.

Lang Stationary Tuning hammer, reintroduced in the 1934 Tonk Piano Supplies Catalogue. From the collection of David Abdalian.

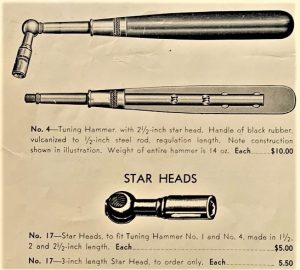

Note how the 1/2″ steel shaft extends almost to the end of the handle. It made for increased stability working with tight tuning pins, and for better durability in general.

USING LANG HAMMERS

Hammers made by Lang show attention to detail in both form and function. The few heads that I have used fit pins up to 2.0, although I’m fairly confident that there were larger special-ordered sockets made that would handle larger tuning pins. The hard rubber handles work well, if a bit clammy; they resist marring and do not require the care in handling necessary for a bored-out tropical hardwood handle. The Lang no. 2 hammer, with set screw, actually works better than the Lang no. 1 hammer shown above; the extension rod is held securely and does not rotate, like some extension hammers with only one set screw.

On Lang no. 1, the clutch works by drawing the internal tube towards the rear of the handle; the exposed rear portion of the brass internal tube is finely threaded, as is the internal part of the handle endpiece. When the handle endpiece is turned clockwise, it draws the the tube back, pulling the split collet along with it. This is the sharply beveled frontmost piece of the ferrule; it is actually a separate part placed right against the ferrule. On the rear, or hidden side, of this collet is a similarly shaped bevel which is mated to a sharply tapered hole in the front of the ferrule, compressing and closing the split collet, and securing the corrugated shaft from slipping. Placing fine threads inside the ‘hard’ rubber handle was the weak link to this design arrangement; pulling all this hardware aft was too much stress given the chosen material. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that replacement parts for this hammer were sold by Tonk Bros. (see bottom of this page) in 1934. But it also demonstrated that the Lang no. 1 was still sufficiently popular enough for further investment 20 years after Lang left pianos for motorcycles.

Despite the shortcomings of the Lang no. 1, on my example, the fluted extension rod is held fairly well, friction-fit within the split collet. It is still possible to tune a piano with the Lang no. 1 in its present condition, and I have done so, but I would not want to use it for an entire day. It is true that the tool is over 100 years old, but it’s also true that the hammer is not beat up or excessively worn out, as the pictures above show.

C.H. Lang, in the 1910 U.S. Census, and living at 6936 Morgan St., Chicago: “Die Maker.” Lang owned his home.

Lang tuning hammers were the most expensive product in the market, at $10.75 in 1905. Was it worth it? A rosewood Erlandsen or Mueller extension hammer including star tipped head cost no more than $7.00 at the time. Hale hammers were offered around $5.00 with a long head and star tip. $10.00 could buy a Hale tuning hammer set with three heads and six tips including the tip wrench. Perhaps the original price explains why the Lang nos. 1 and 2 hammers are not exactly rare, but uncommonly found in the wild. There are two reasons, I believe, why the Lang no 1 did not survive long-term, competing with the Hale hammer: in sum, the high price, and the inherent design issue described above.

“Ferrules of perfectly seamless steel.” This was a reference to Julius Erlandsen’s practice of rolling and seaming flat stock of German Silver to make his ferrules. His father, Napoleon, did not seam his; nevertheless, the seaming was of impeccable quality, and the German Silver, beautiful.

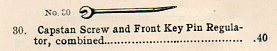

Heads could be custom-made, if needed.

The following offer was part of a ready-made toolkit. There is some general variation between the sizes of tuning pin sockets made during this period. It must have been standard practice in the trade to custom-machine tuning heads for the varying requirements of the tuners at the time.

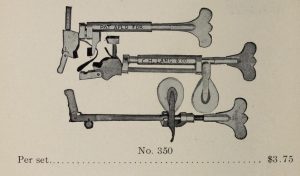

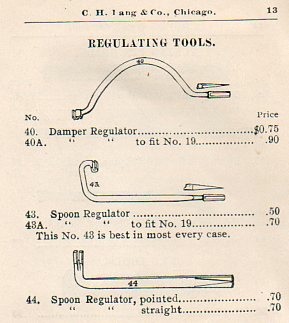

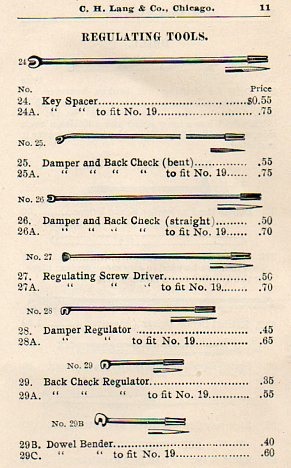

C. H. Lang Chicago inscribed regulating tools with their original attached handles: fore/aft wire bender; upright spoon bender, key spacer; let-off adjuster.

These tools have an optional proprietary socket, for the Lang combination handle, or the traditional tang for fitting into a handle.

Lang capstan wrench (pointed end) and key pin turning tool. Today, turning front rail pins is frowned upon.

Lang Capstan Regulating tool.

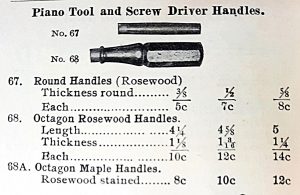

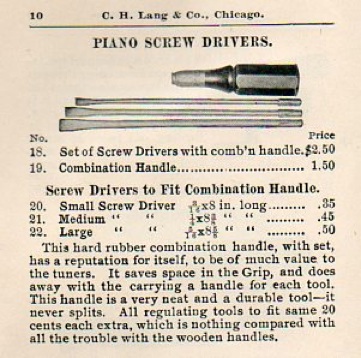

Handle shown in catalog.

Lang combination handles, hard rubber.

Shown below is a combination handle, with ebonite instead of hardwood, and metalwork that matches that of the Lang machine shop. This adjustable handle was designed to take the standard regulating tools that we use today, but with a friction fit, rather than a collet. Not included in the 1905 Lang piano tool catalogue.

Looking surprisingly modern, Lang’s grand regulating tool was intended for adjusting drop, balancier, jack, and fine adjustment on some damper underlevers.

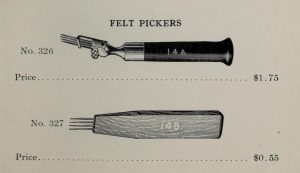

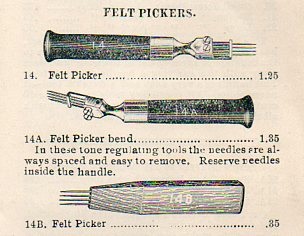

L&H voicing tools, identical to Lang’s because the tooling was not changed. Hale adopted this style of voicing tool, enlarged it slightly, and added set screws for each of the four needles. This style was continued by Hale until the 1990s and variations of this design are still produced today.

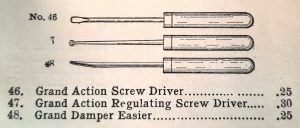

Lang small screwdriver for grand drop screws; grand action regulating tool; umbrella wire damper bushing easer.

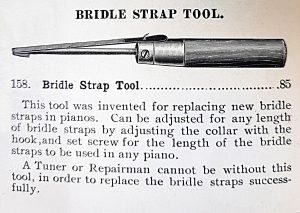

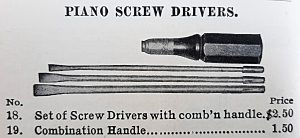

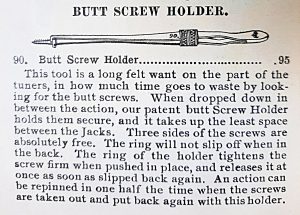

1905 catalog.

Higel did not bother to erase Lang’s original catalogue numbers showing on these voicing tools.

C.H. Lang rarely used rosewood in his tools; it showed that he regarded his voicing tool as special. Lang tuning tool handles were primarily ebonite (hard rubber); regulating tool handles were ebonite, stained hardwood, or mahogany. The Lyon & Healy voicing tool shown here has a mahogany handle, which was less expensive than rosewood, even then.

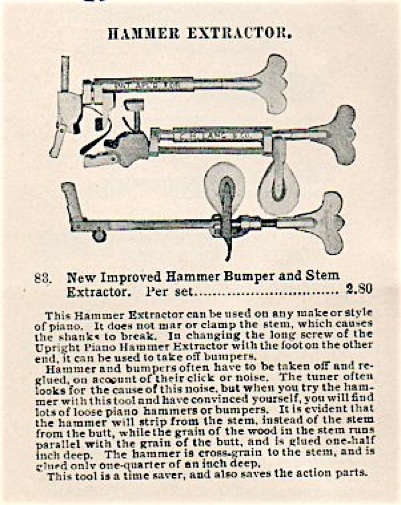

Lang’s description of his Hammer Extractor, an d explanation of wood grain orientation in the upright butt, shank, and hammer moulding.

Lang patent for a hammer extractor (by no means the genesis of this concept).

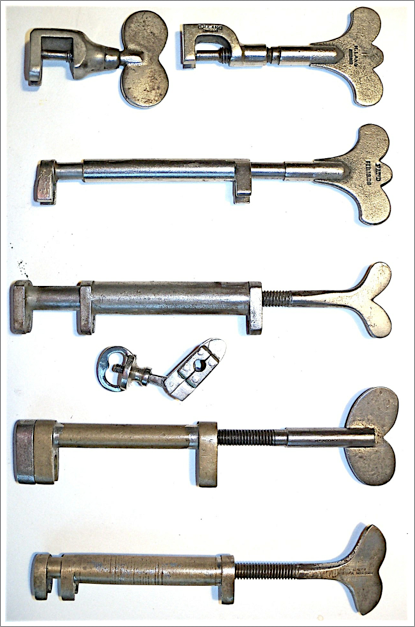

A selection of hammer extracting tools:

- Top left: unmarked, probably Erlandsen. For grands.

- Top right: Lang grand extractor

- Lang, for uprights

- Tuner’s Supply (Hale), upright

- Hammershank clamp, upright

- Hammacher Schlemmer, upright

- Boston Tuner’s Outfit Co., upright

Lang also held patents for a key ivory clamp and a screwdriver holder, but there were precedents for those ideas as well.

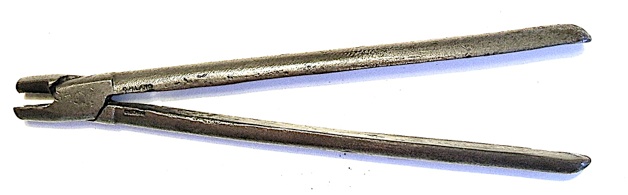

C. H. Lang action wire bending pliers. A version of these has been copied and is still sold by Schaff Piano Supply in Chicago.

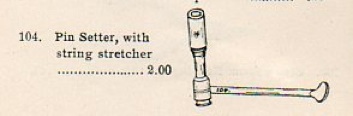

Lang tuning pin setter, used to drive tuning pins further into the pinblock.

Lang tuning pin setter, used to drive tuning pins further into the pinblock.

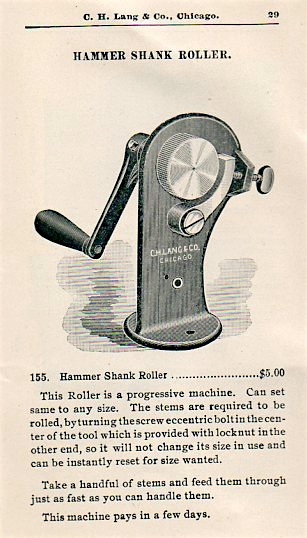

Lang hammershank knurling machine, mounted on block for placement in a bench vise, as found in the pianomaker Hornung estate sale in 1990.

The construction is heavily cast.

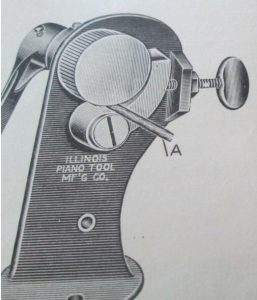

Lang hammer shank knurling tool, sold by Shapiro Piano and Instrument Supplies (1913), and rebadged “Illinois Piano Tool Mfg. Co.”

Lyon & Healy Piano String Lifter and Spacer, identical to Lang’s.

This is the earliest that I’ve seen the combination of a coil lifter with string spacer, c. 1905.

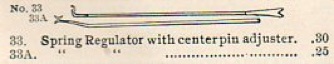

Lang spring adjusters, with a tool to squeeze in between flanges and push centerpins that have walked out back in their respective flanges.

Lang spring adjusters, with a sneaky tool to squeeze in between flanges and push centerpins that have walked out back in their respective flanges. No one ever does that, right?

L&H spring adjuster.

Lang’s Transition from Piano Tools to Harley Davidson Motorcycles

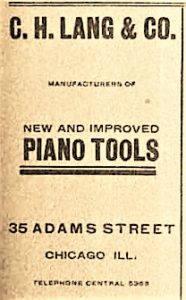

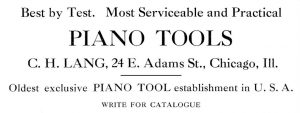

This was one of the last Lang Advertisements before the Lyon & Healy buyout. I am not sure what Lang’s calculus was regarding him calling his business the “Oldest exclusive PIANO TOOL establishment in the U.S.A.” Hale’s Tuners’ Supply Co. was older, having been founded 1885. Perhaps Lang was taking into account Hale’s diversions into his oil and game hunting businesses. But Lang’s Harley Davidson Dealership was already larger than his piano business in 1913.

A more likely possibility was that Lang was indirectly stating that he sold tools only out of his piano business, and that he did not trade in piano supplies generally. It’s difficult to know why Lang thought conveying that to the piano market would be an advantage for him. When Lyon & Healy took over, they immediately included piano supplies, which naturally, working piano technicians needed.

Announcement of Lyon & Healy buyout of C.H. Lang Piano Tool Maker, in “Tuners’ Magazine,” in June, 1914.

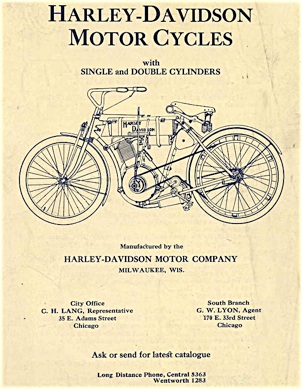

Early Harley Davidson catalog with Lang as representative working out of 35 E. Adams St.

Even in 1904, Lang had his sights set on a future with Harley Davidson. With no explanation, he put this early Harley on the back exterior cover of his 1905 piano supply catalog.

Carl H. Lang declared his profession as a motorcycle dealer in the 1920 US census, In 1926, C.H. Lang retired from selling Harley Davidson motorcycles. During the Great Depression, Lang needed to return to work for a period of time, primarily as a mechanic.

The following quote described C.H. Lang’s transition from the piano business to the motorcycle business. It was taken from HDforums.com

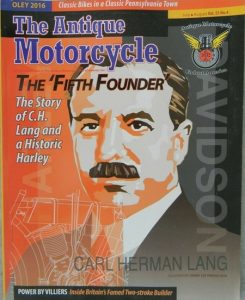

CH Lang is mentioned in articles in two recent issues of The Antique Motorcycle which is the AMCA magazine. Lang was the first H-D dealer and also an early H-D director and shareholder.

In Sept 1904 Lang was among members of the Chicago MC who went to see motorcycle racing at the Wisconsin State Fair Park. Two H-Ds competed along with several other makes. Later on Lang apparently bought one of the first three H-Ds produced and the bike he obtained may have been the next one made after the two that were raced at the State Fair Park. Lang proposed that he become a ‘general sales agent’ and the first H-D dealer, all as a sideline to his piano-tuning tool business in Chicago. H-D agreed and as a result Lang handled three 1905 H-Ds out of a production run that likely totaled five to eight machines.

In 1907 Lang developed a two-speed planetary-style trans and clutch (US Patent No. 908,583—‘Changeable Speed Gearing for Motorcycles’) that could be fitted to a Harley and it was unveiled at Curtis Hill near Milwaukee in May that year.

H-D incorporated in Sept 1907 but apparently Lang only took five shares. In 1912 he moved his dealership from 35 E Adams St to 1704 S Michigan Ave where he occupied a three-storey brick structure while using another building for storage of bikes and parts. By this time he was selling or distributing nearly 1,000 Harleys per year. In 1914 he disposed of his piano tool business and devoted all his energy to the motorcycle trade.

In 1920, C.H. Lang lived at 4756 Indiana Ave., Chicago, and was a “Motorcycle Agent.” selling Harley Davidsons.

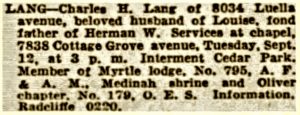

By the 1920s he increasingly turned over management of the dealership to his son Herman. Lang retired in 1926 but apparently Herman wasn’t interested in running the business so Lang transferred things to Frank Kemper who moved the operation to 1507 S Michigan Ave. Lang died in 1944.

C.H. Lang lived at 8034 Luella Ave., Chicago, and due to the hardships of the Great Depression had to resort to working as a “Mechanic.” 1930 U.S. Census.

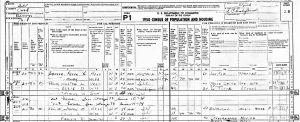

C.H. Lang was still living on Luella Ave, Chicago in 1940 (U.S. Census), and was fully retired at age 71.

C.H. Lang Harley Davidson Dealership, circa 1912, at 1704 Michigan Ave., Chicago. Photo from Harley Davidson Archives.

Carl Herman passed away on 9 September, 1944.

LYON & HEALY

Lyon and Healy’s motto was “everything in music.” They either sold or retailed just about any Western musical instrument in popular use during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They even made pipe organs. Lyon and Healy was also a major music publisher. As the years progressed, L&H began selling off its acquisitions and concentrated on what they did best, which was making one of the best harps in the world. Their style 23 harp introduced in 1890 is still being made today by a much smaller company.

At first Lyon & Healy advertised “Lang Tools” profusely, but after a few years the name “Lang” was withdrawn from Lyon & Healy catalogues as well as their advertising. Probably because Lyon and Healy had such a well recognized name, Lyon and Healy could conceal the source of their piano tools; Lang’s name was removed from all the tools as well.

In 1916, Lyon & Healy opened an extravagant retail showroom at Jackson Blvd. & Wabash Ave., formerly the site of the Hotel Wellington.

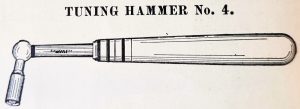

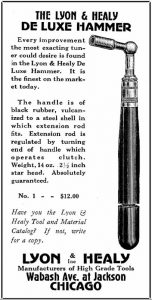

Rebadged Lyon & Healy Stationary Professional tuning hammer (Lang No. 4). Advertisement in “The Tuners Journal,” September, 1921.

Rebadged Lyon & Healy Extension Professional tuning hammer (Lang No. 1). Advertisement in Tuners Journal,” June, 1924.

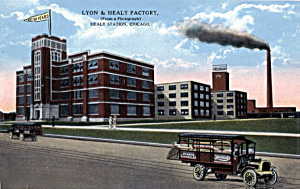

Lyon and Healy’s piano factory was established on Fullerton Ave in Chicago in 1913; before that, L.& H. branded other maker’s pianos. In May, 1914, C.H. Lang’s piano toolmaking shop was moved to the Lyon & Healy Fullerton Ave. plant, and continued under the direction of Superintendent F.A. Lang, Carl Herman Lang’s brother. F. A. Lang had been managing the C.H. Lang Piano Tool Shop since 1905. Most of the former C.H. Lang machinists also continued to make piano tools under the employment of Lyon & Healy, at the Fullerton Avenue location.

“The manufacturing activities of Lyon & Healy are carried on in a large new fireproof factory building in Fullerton Avenue about six miles from the downtown center of the city. Here are where the Lyon & Healy harps in their various styles, the Lyon & Healy piano in uprights, grands, and player pianos are made. Washburn pianos, designed for export, a large variety of band, orchestral, and other instruments and minor lines of musical merchandise. The ideas which characterize the house of Lyon & Healy are notably dominant in the manufacturing department.”

–Chicago Tribune, 21 May, 1916

In 1927, L.& H. sold Fullerton Ave. to Mills Novelty Co., makers of the Mills Violano-Virtuoso, and other music arcade coin operated machines.

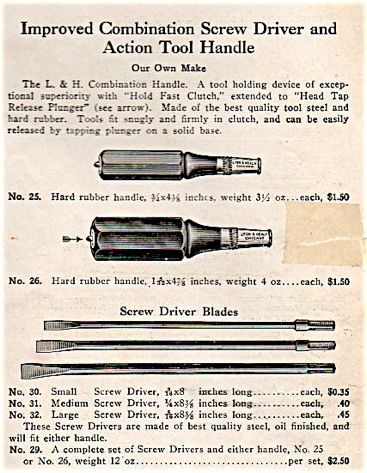

L&H made a few minor changes to their line of tools. Most notably, their combination handles changed twice.

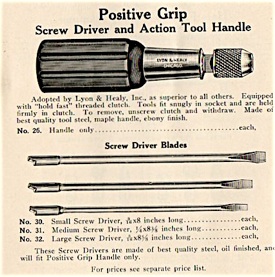

L.& H. Combination Handle, version 2, 1917.

“Tools fit snugly and firmly in clutch, and can be easily released by tapping plunger on a solid base.” –As long as that solid base is not a piano cabinet.

Lang Combination handle, version 1, in hard rubber, as offered in the Higel, Toronto 1906 Catalogue.

Lyon & Healy combination tool set. This second version was the only handle that bore any resemblance to the former Lang product.

L.& H. Combination handle, version 3. From 1926 L.& H. Catalogue.

Otherwise, 97% of Lang’s designs remained unchanged save for the signature.

This was the configuration that had become an industry standard by then, already adopted by Hale, American Piano Supply, and others.

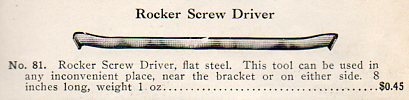

Rocker capstan offset screwdriver.

L. & H. Pin extractor.

Pin extractor.

Tonk Brothers Company

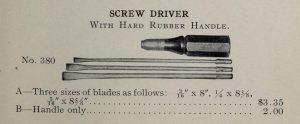

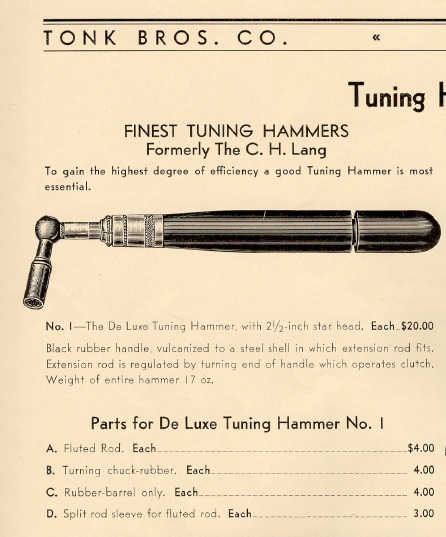

Replacement parts were offered for repair and refurbishment of older, worn hammers.

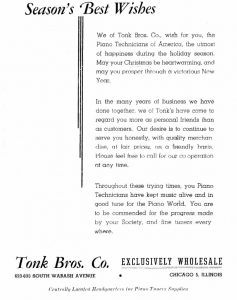

The Tonk Brothers Company bought out Lyon and Healy’s piano supply division in 1928. Tonk Bros. Co., located at 623 South Wabash Ave. in Chicago, was a large musical instrument dealer and wholesaler, well established since the late 19th century. Tonk Bros. rehabilitated the Lang name, attributing credit to the original designer and maker. This was 20 years after Lang sold out to Lyon and Healy, and around 40 years after the tool was originally conceived. Here is the Lang No. 1 tuning hammer, as sold by Tonk Bros. in 1934.

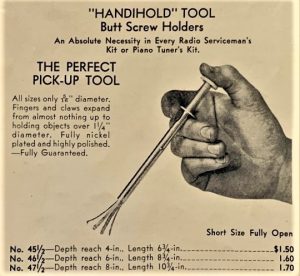

“Handihold” Tool, for butt screws, and damper underlever screws. Image from 1934 Tonk Bros. Catalogue. From collection of David Abdalian.

The Handihold Tool was hollow in the center, which was intended to assist sight-impaired technicians install and remove difficult to reach screws, such as the upright hammer butt screw, or the grand damper underlever screw.

Unbeknownst to most members of the piano trade, this Holiday Greeting was, in fact, a goodbye from Tonk Bros. Co. Less than a month after this was published, Tonk Brothers Company sold their piano supply division to Continental Music.

Tonk Bros. served as steady stewards of their piano supply business, through the lean depression years, and the turbulent war years. Then, after WW II, when American industry had been on a war footing, the transition back to production for domestic purposes would take several more years. Luxury items, such as the piano (and supplies), were not top priority.

One year after hostilities ceased Tonk Bros. must have seen the writing on the wall, and decided then and there, that it was not worth it for them.

Joe Kulicek

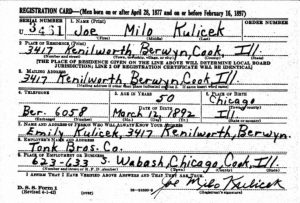

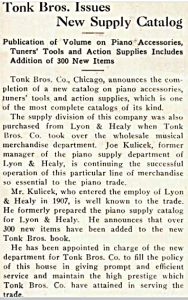

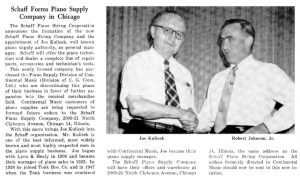

Tonk Brothers Company owned their piano supply business until January, 1947, when Continental Music took over. Schaff bought the business from Continental in May, 1955. A constant in all of this was Joe Kulicek (1892-1979), who was a manager at Lyon and Healy from the 1920s, through Tonk and Continental, and into the early days at Schaff with Bob Johnson, Jr. Thanks to David Abdalian for this timeline.

Joe Kulicek, 18, Clerk, Lyon & Healy Music (hired 1907), 1444 South Avers Ave., Cicero, IL. 1910 U.S. Census.

Joe Kulicek moved from General Manager of Piano Supplies, Lyon & Healy, to Manager of Tonk Bros., “Music Trade Review, 3 November, 1928.

Joe Kulicek, “Salesman” Tonk Brothers Music, living at 3417 Kenilworth, Cicero, IL. 1930 U.S. Census.

Continental Music’s Center Pin Holder, as shown in “The Piano Technician,” October 1948. Rosewood Center Pin Holders were generally phased out during the WWI era.

Joe Kulicek, “Salesman,” Continental Music, living at 3417 Kenilworth, Cicero, IL. 1950 U.S. Census.

Continental Music, (630 S. Wabash) which took over the Piano Supplies Division of Tonk Brothers (623 S. Wabash) in January 1947, was owned by C.G. Conn, who manufactured the Stroboconn, introduced in 1936, and the more portable Strobotuner, introduced in 1954. C. G. Conn’s core business, however, was manufacturing brass and wind band instruments. Buying Tonk Brothers Piano Supplies Division would have given C.G. Conn another means of distribution for their electronic tuning devices, and provided a way forward to establish a new market with piano tuners, and to gain market dominance within this new field.

Conn Strobotuner, ” Available through leading music stores everywhere.” From “The Tuners Journal,” December, 1954.

But Conn did not take full advantage of selling their Stroboconn through Continental Music; at the back of the 1953 Continental Music Catalogue, there was a full page spread on the Stroboconn, and piano tuners were directed to contact C.G. Conn Electronics Department for prices and further information. When the Strobotuner was introduced, in late 1954, all this changed, and the customer could purchase the Strobotuner from a myriad of music stores. In May 1955, Conn sold the Piano Supply Division of Continental Music to Robert E. Johnson Sr. and Jr., who owned the Schaff Piano String Company, which had been providing custom wound bass strings since 1884 in Chicago.

In the mid-1950s, C.G. Conn moved a significant amount of their capitol away from their core business of selling brass and wind instruments, and invested in electronic organs, which were all the rage in the 1950s and early 1960s. Unfortunately, the electronic organ business was boom and bust for C.G.Conn, and they filed for bankruptcy in 1969.

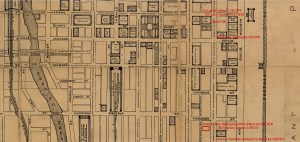

“Map of the business center of the city of Chicago in 1905,” by Chicago Directory Co. Section showing Wabash Ave. and Piano Supply Houses.

C.H. Lang was at 35 E. Adams, which would have been within, or directly next door to the old Lyon & Healy Building at the southwest corner of Adams St. and Wabash Ave. However, in late 1910, C.H. Lang moved to the fifth floor of 24 E. Adams, which was on the northwest corner of Adams St. and Wabash Ave. In 1916, Lyon & Healy opened an extravagant retail showroom at Jackson Blvd. & Wabash Ave., formerly the site of the Hotel Wellington. Tonk Brothers occupied the Studebaker Building at 623 Wabash and traded in piano supplies there from 1928 to 1947. Continental Music took over from Tonk Brothers in January, 1947, and ran their operation from the Dexter Building at 630 Wabash Ave., then moved to 1810 Ridge Ave., Evanston, IL in May 1951. Continental Music remained in Evanston until May 1955, when they sold to Robert Johnson Sr. and Jr., who owned Schaff Piano String Co. at 2021 Clybourn Ave.

Joe Kulicek also manufactured a few piano tools of his own, including tuning hammers and hammer extractors. But it was a mystery to me why his employers allowed him to do this.

Joe Kulicek adjustable tuning hammer, marked “Joe Kulicek” on handle and tip, with floating collet and one piece head, c. 1950. It appears to be the same tool as the early Schaff hammers.

Kulicek’s extension tuning handle, with a red polymer handle and shiny plated metal hardware, reminds me of the Millers Falls “Buck Rogers” planes (and other tools), which were futuristic in design, and had red handles made of Tennessee Eastman Tenite #2, a cellulosic plastic, which was developed in 1929.

A significant amount of piano tools sold by Continental Music (1947-1955) and Schaff Piano Supply Co. (1955-2000) were made in the machine shop of AMS Piano Tools, founded by Rudy Adams (1900-2005) in Chicago, in 1938. Schaff now uses their in-house machine shop based in Clifton N.J., purchased from American Piano Supply Co. in 2000 for their tool production.

Schaff Piano String Co. bought out the Piano Supplies Division of Continental Music. From “The Tuners’ Journal,” June, 1955.

The new Schaff Piano Supply immediately published an advertisement–in a tacky ’50s style– announcing Joe Kulicek as General Manager. From “The Tuners’ Journal, June, 1955.

Joe Kulicek started working at Lyon & Healy in 1906. Many piano technicians would have known Joe Kulicek since the 1920s, when he was manager of the Piano Supplies Division. His was a long career.

Joe Kulicek, Schaff Advertisement, in the 1958 PTG Convention, Washington D.C. From “The Piano Technician,” Spring, 1958.