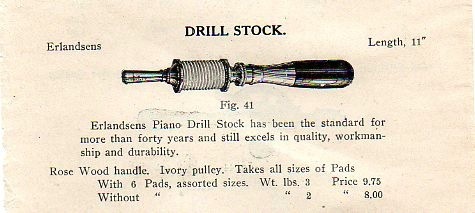

Napoleon and Julius Erlandsen made a drill stock that became the standard of the piano industry. For a historical summary of their careers that spanned from 1863 to after 1940, please refer to my page on New York Piano Planes, Part I.

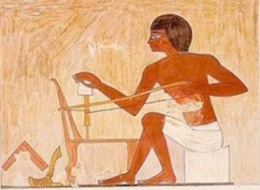

Ancient Egyptian craftsman: work on a chair with early bow drill.

This ancient tool, which was depicted in Egyptian hieroglyphs, is almost as old as the invention of fire, as the first versions of it were used to start fires and to drill holes in stones and beads. They were driven by a bow held in the opposing hand, and were capable of producing precision work when used by skilled craftspeople. Bows were moved back and forth, in a steady reciprocal motion, somewhat like a cellist might play.

Old Chinese craftsman, with bow drill. From “If These Pots Could Talk,” by Ivor Noel Hume.

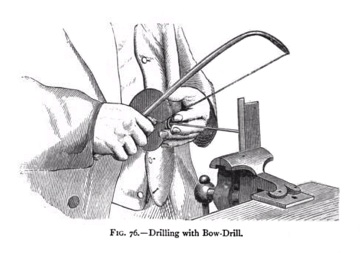

Nineteenth century bow drill, with breastplate.

Samuel Wolfenden, a British pianomaker and author of “A Treatise on the Art of Pianoforte Construction,” (1927) wrote about the application of bow drills in piano work:

…the old stock, used with a weak bow for bridges and a strong one for wrest-planks, is superior. For use with the bow, the drills for bridge pins should be made of steel wire, with rather long points, and half the diameter filed away, leaving a cutting edge on each side. Made thus, they bring out all the core, which—if the drill is stuck into a piece of hard soap—falls away, and the point is cooled and lubricated for the next hole.

For drilling wrest-pin holes, thin “quill” bits are best. Very accurate fitting is needed, and it is wise to have a selection with very small differences in the diameters of the resultant holes, so that differences in the hardness of the wrest-planks (often considerable) may be met, and also small differences in the gauge of wrest-pins for it frequently happens that the pins are not quite of the nominal diameter. It is astonishing how much difference there can be in the tightness of wrest-pins arising from either of these causes.

When I read this, I was rather surprised to learn that in the rather conservative, even backward-looking English piano industry of that time, bow drills were used for heavier structural work, such as drilling pinblock holes. I knew that they were traditionally used for drilling out harpsichord wrest-plank holes, but that was in the eighteenth century, and the holes drilled for harpsichord tuning pins were considerably smaller. I had assumed that the piano, a product of the industrial revolution, had utilized either a steam driven drill press run by belt drive, or a hand-cranked drill press for this procedure, as shown on my pianomaker’s braces page. These other methods were probably employed in England as well.

In North America, bow drills were traditionally used for relatively delicate drilling, such as making holes for the bridge pins, and there are about 470 holes per piano, for that task alone! Many of the smaller holes for various screws were also made with this tool. Precision drilling was critical before 1850, because the screws lacked a point, or gimlet, to aid in starting in the drilled hole, but this predates Erlandsen’s bow drill, which was introduced when Napoleon Erlandsen set up shop in 1863.

This drill is c. 1905.

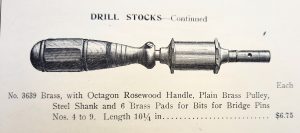

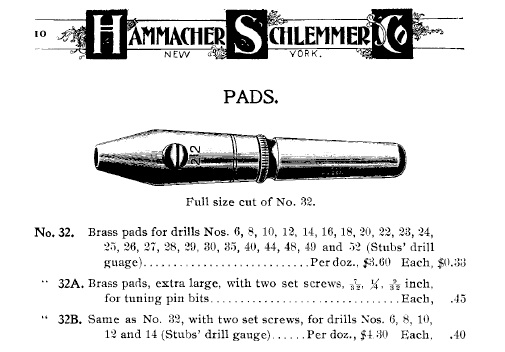

Drill pads, Erlandsen. 1885 H.S. & Co. N.Y. Catalogue.

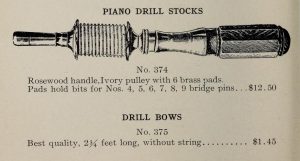

Drill pads were friction fit into the tapered socket of the drill stock, and the bit was fixed into the socket of the pad by tightening the set screw, or screws. The bits included in the 1900 H. S. catalogue were mostly the spoon type, and the various sizes and their intended uses were covered over several pages. Specific applications described were for bridge pins, tuning pins, lyre rods, center key counterbores, countersinks, and general uses.

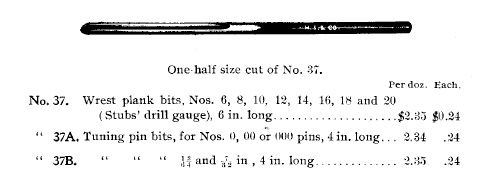

Spoon bits for wrest planks.

Drill pads, Erlandsen.

Drill pads, Erlandsen. One of these pads is signed by both Napoleon and Julius Erlandsen–probably during the transition period–transferring the business from father to son circa 1894. The small steel pad, second from left, holds bits for bridge pin drilling (ignore the spiral bit), and the two large pads, 1/4″ and 17/64″ are sizes that would be used for drilling out pinblock material for size 1.0 to 2.0 tuning pins, the range of common sizes for new pianos in the late 19th, early 20th centuries. These are very scarce, and are almost never found separated from a drill stock.

Spade type reciprocating drill bits.

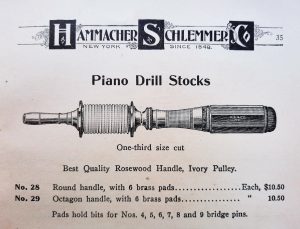

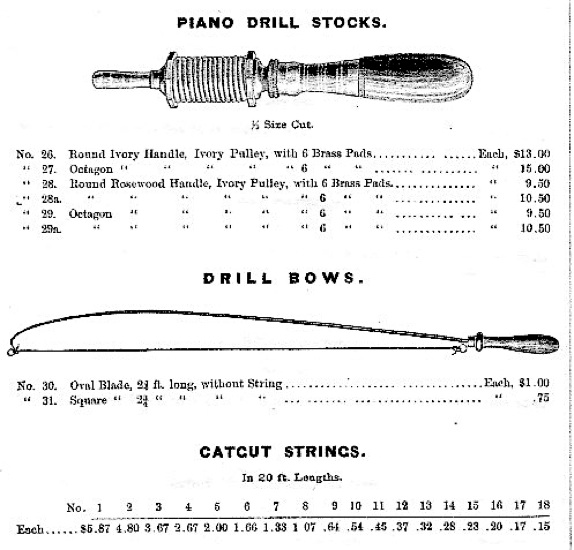

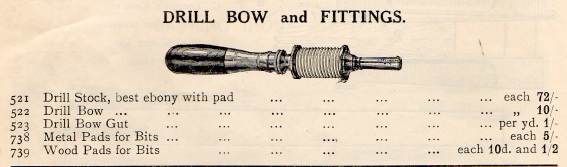

Erlandsen drill stock, as sold in the Hammacher Schlemmer Catalog for 1885.

Note the version available with ivory handle and pulley for $15.00. Of course, this was a lot of money in 1885, and there was little demand then for such a prided extravagance. Yet, ivory drill stocks are coveted between general tool aficionados, and can sell for over $2,000.00 today. Julius Erlandsen appeared in the 1930 census, living an apparently very simple life, renting an apartment and living alone. He did not marry, and lived with his mother until she passed away. This makes me wonder how much the Erlandsen family benefited financially from wholesaling their products to retailers.

“Catgut” was actually made from sheep intestines. Catgut strings are still used for early musical instruments and for stringing some old fashioned tennis racquets. I found no documentation for the shoelace type leather strips that are typically put on bow drills during the last several decades.

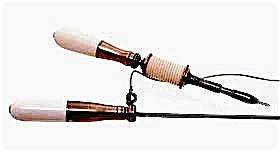

Erlandsen ivory bow and drill.

Ivory bow drill stock with George Buck features. Sold in David Stanley Auctions, February 2019. Photo by David Stanley Auctions.

This ivory bow drill stock was probably made by the same toolmaker who supplied George Buck with his bow drills from the 1830s up to 1920, but this maker remains unknown. Early features included the use of an ivory handle, a chuck that was incorporated into the spool, and hidden metalwork with ornate knurling. This particular bow drill was engraved with the date of 1840. Photos by David Stanley Auctions, February, 2019.

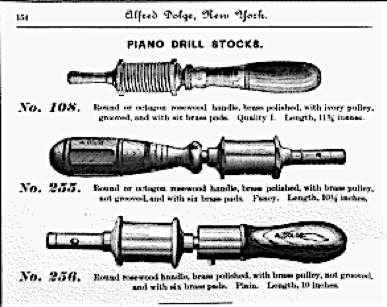

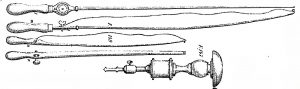

Three bow drills, offered by Alfred Dolge in his 1892 catalogue. Erlandsen’s, shown on top, was sold as the choice with #1 quality; the others were less expensive.

Six piano drill stocks, with pads and drill bits, top to bottom: Leon Pinet, Paris; George Buck, London; Erlandsen, New York; attributed to Lauritz Brandt, New York; Napoleon Erlandsen; unsigned New York type with brass pulley and ebony handle.

N. Erlandsen bow drill with triple knurling on ferrule, space between handle and spool, and turning on chuck, all features similar to some of those by Lauritz Brandt.

New York, bow drill stock, earlier type, c.1840s to 1860s. Offered by Tollner of New York (1850s) and Wilkinson of Boston (1860s), and probably other dealers.

New York bow drill, very similar to No. 255 in the Alfred Dolge catalogue, shown above. The primary difference with this example is that the brass spool is threaded.

New York Bow Drill, 11″, with ebony spool, rosewood handle, and Goodell chuck from their No. 230 brace.

Even the more basic piano drills show precision and elegance. Here is the rear view of the ebony handled drillstock, showing a steel friction adjustment screw bushed in brass. Mirrored from the brass spool with triple step, the handle ferrule shows the same detailing.

N. Erlandsen bow drill partially disassembled.

N. Erlandsen bow drill partially disassembled. An adjustment screw at the back of the ferrule adjusts the amount of play/friction for the rotation of the spindle. Ivory spindles would tend to crack under the stress of constantly reversing direction while driven by the bowstring.

Napoleon Erlandsen bow drill stock, with Eicke 1882 patent, 8 assorted pads, and small bow. Photo of set from Brown Antique Tool Auctions, October, 2022.

Several methods were employed to fix these spindles to the steel center shaft: a tight pressure fitting, fixing with a pin drilled through the steel shaft and into the ivory, and threading both the shaft and the spindle. Louis Eicke patented the latter method, and an Erlandsen-type drill stock is depicted in his patent drawing. Eicke’s solution proved generally successful in avoiding split and cracked ivory spindles.

Using fencing foils to make bows was a common practice. Because many craftspeople made their own bows, and the possibility that bows could be purchased locally, they were sometimes omitted from piano supply catalogs.

Some instructions on making a bow:

The main body of the bow is made from an old epee or foil, at the tip of which one drills a hole, to attach one end of the cord. At the opposite end is a metal ring to attach the other end of the cord.

—Jean Jacques Perret, The Art of the Cutler, 1771.

Buck Ebony bow drill set. The Solingen wrought steel was bent hot.

George Buck trading from 245, 247, and 242 Tottenham Court Road, London, also sold specialized piano tools, such as regulating tools, as well as tools for other trades. In the photos above and below, the bow is not the original; I made this one with an African Blackwood handle, and a converted antique French fencing foil, with Solingen steel and gut string. The original bow featured a ratchet adjustment, which set the string tension between the bow ends and around looped pulley, to the appropriate amount of friction. Bob Garay has a website on bow drills, which includes a number of New York bow drills made for the piano trade, as well as a photo of the original Buck bow.

A 30″ bow can rotate the spool efficiently.

Old bow, probably nineteenth century, with details of the extremities.

Looking for a pianomakers’ tool business named Gauchois, or even just a Paris-based “Gauchois” toolmaker, I came up dry; Gauchois is not a common surname. I did fine a Jean Baptiste Onesime Cauchois, a piano casemaker, who lived in Paris, and died in 1897. Its possible that Onesime ran a side business for his fellow workers. The odds that this Cauchois is ‘our’ toolmaker is probably 40% at best.

French pianomakers’ bow drill pad, works on set screw, not taper, like American and English versions.

One Buck Bow drill stock is all rosewood, and the other is dark rosewood with the spool possibly ebony. The rosewood drill is shorter and narrower than the darker one, but the shape of the handles suggest that they were made at the same time. Both Buck drills likely were used in the same factory shop floor.

English Bow drill stock, early to mid-19th century, showing ornate knurling hidden inside handle. Even the New York bow drill makers did not go to trouble of embellishing unseen surfaces.

Various ratcheting and smaller drillstock bows. Photo from Skinner Auction Co., c. 2012.

Various drill bows, with ratcheting string adjusters. (photo Skinner Auction Co.) Small bows shown at the top left were used by watchmakers and jewelers, and are also about the same size as those used by early dentists. They would be held by the hand in the middle of the bow, therefore, a handle was not necessary. Examples such as these would have been made of brass, whalebone, or steel. The four bows with handles are shorter and somewhat smaller than those typically used for piano work. Bows for the Erlandsen or the Buck drills usually range from two and a half to three feet, enabling the craftsperson to develop more speed and create more inertia. I imagine that it must have been a challenge to use these long bows inside the piano, while still managing to avoid striking the inside of the case.

Diminutive drills; these are sizes that would have been used with the bows shown at the top of the photo above:

Both of these drills have rosewood handles; the ornate drill on the right has a handle in the German style.

English ratcheting bow.

Bow with ratchet adjustment, England, Knowing where to tie the string, and allowing for the amount of length needed to encircle the drillstock pulley with the proper tightness/ friction took skill and practice. This device eliminated that part of the challenge of using a bow drill, which is now a lost art. String is wound on the key spindle on the opposite side.

L. Pinet, Paris bow and drill with ivory handles, gunmetal, brass, and steel hardware. For piano work.

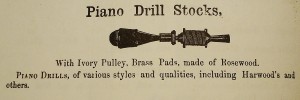

Similar drill stock in A.J. Wilkinson & Co., Boston 1867 catalogue. If anyone knows about the Harwood bow drill, please let me know.

Looking again for a Harwood, who made bow drills in the middle third of the 19th century, I did not find conclusive results. There was a Harwood firm specialising in cutlery, silverware, and hardware (i.e., tools) working out of Sheffield in the late 18th, early 19th century. In the 1820s John (d. 1824) and Robert Unwin Harwood (1798-1863) moved to Montreal, Canada, where they established a Montreal branch of the Harwood firm. The Robert Unwin Harwood building, erected in 1824, still stands at 20-22 Rue Saint Paul in Montreal. Robert Unwin ran a work cooperative that was based out of a large mill he had built in the Montreal suburbs.

Not sure if this actually the Harwood type, or if it has “R. Fishley” or another maker written inside, as the wooden handle is frozen (for now) on the brass hardware. Bob Garay has a similar bow drill stock inscribed with “R. Fishley.”

Another Tollner-type bow drill stock, with ivory handle and threaded brass and bronze spool. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auctions, October, 2022.

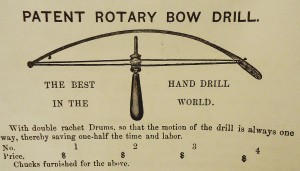

Another interesting idea that has come and gone. A.J. Wilkinson & Co., Boston catalogue, c 1867

Erlandsen drill stock, with countersink bit and bow Photo from Martin Donnelly tools.

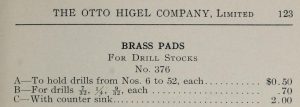

Julius Erlandsen Bow Drill Stock and Bow, as offered in the Otto Higel Piano Supplies Catalogue of 1906.

The last catalogue entry showing the Erlandsen bow drill, or any piano maker’s bow drill for that matter, was in J.& J. Goddard’s no. 80 trade list, circa 1938–1939:

Goddard’s no. 80 trade list, circa 1938–1939, depicting the Erlandsen bow drill stock:

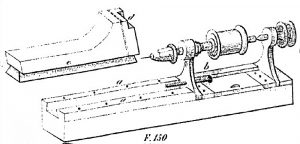

Sometimes the drill had a fixed placement, as in this illustration from Il Pianoforte; Guida Pratica by Giacomo Ferdinando Sievers, published 1868 by Ghio, Napoli. This enables drilling with one hand.

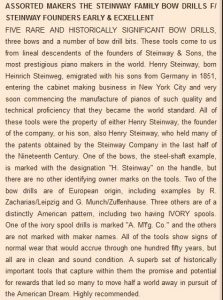

From Sievers. Some adjustable bows, and a drillstock typical of those made on the European mainland, primarily Germany. Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg brought a number of these from Seesen, Germany to New York, when he emigrated in 1850.

MJD Auctions, April 19th, 2008. Held just a few months before the death of Henry Z. Steinway at age 93 on September 18th, 2008. There was at least one other auction lot of bow drills from the Steinway estate.

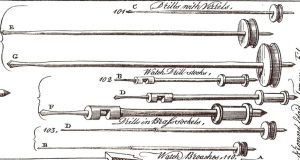

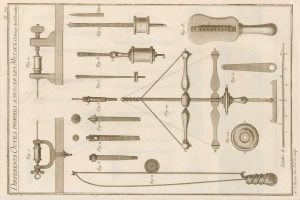

André Jacob Roubo, L’Art du Menuisier (The Art of the Joiner), 1769-1774; plate 319. Various drills.

![Diderot, vol. 5, Plate 10: Music Instrument Making, One and Double-Ended [treadel] Lathes Used by Makers of Wind Instruments, Flutes, Oboes, Clarinets, Etc. circa 1767.](https://mshepherdpiano.com/wp-content/uploads/Diderot-Treade-lathe-190x300.jpg)

Diderot, vol. 5, Plate 10: Music Instrument Making, One and Double-Ended [treadle] Lathes Used by Makers of Wind Instruments, Flutes, Oboes, Clarinets, Etc. circa 1767.

Bow drills began to be phased out after the invention of the Black and Decker portable electric drill c. 1917, but there are some instrument makers and jewelers who still use them. This is is a picture of stringed-instrument bow maker Ken Altman using a fixed bow drill for part of the process of making a bow (photo from www.altmanbows.com):

Another fixed bow drill in use at an old-school workshop. Photo from Ian Burkard: www.maestronet.com/forum

Artisan using a bow drill in the process of making a sitar at the shop “od Radha Krishna Sharma” in Kolkata. From stephanmikes.com.

Italian bow drill, for use in artistic stonework.

Same drill, with second person providing power rather than one person using a bow. Working in stone would require the security of two hands on the drillstock for some tasks.

Alberti Foret, or Bow Drill, for bowmakers, with modern adjustment features.

New bow drill,with bits for working in stone, called a “violin drill.”