© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

EARLY METAL PLANES: BLOCK, MITRE, AND LUTHIER

This section includes a good number of early European metal planes from the 16th through 18th century, including both small block-type and instrument makers planes as well as mitre planes. Some 19th and 20th century instrument planes are also included as there was and is a link between them and the much older planes. A limited number of these early Continental planes survive, and a commensurately small number of photos of these planes exist. A notable portion of examples that remain extant are represented here. Because of this scarcity, I have used this webpage as a repository of images for these rare artifacts. I have include sources of the photographs where possible. Hopefully, this page will serve as a resource for those that are interested in this specialized subject.

In William Louis Goodman’s seminal history book on antique tools, “The History of Woodworking Tools” (1964), Goodman observed that the early “shoe-shaped” block plane, or Vergatthobel, in German, originated in the late Medieval Period. The word was derived from the Middle High German word ‘Vergatten,’ which means to fit together; for example, to join the edges of a picture frame. These were not all block planes in the sense that we know block planes today because most of them (but not all) were set up with the cutting iron bevel down.

Looking back to the Roman period, Goodman described the longevity and continuity of metal planes, or at least, planes with a metal sole:

“…planes with metal soles and side plates were standard types in Roman times, and during the Dark Ages and right throught the Middle Ages small block planes were frequently made with a metal sole and a bone or wooden core. These small block planes were very useful to violin and other musical-instrument makers”

Goodman continued, describing the 6 metal luthier planes on display at the Stradivarius Museum in Cremona, Italy. These planes, which have a smaller size range, are shown later on this page.

With the steep cutting angle on this early ‘block’ plane, the iron would have to be bevel down. Photo from iluthier.com 2003 (defunct).

A key to determining a bevel up or down position, is examples where the opposite end of the iron was bent into a curve or scroll: when bent, they were invariably bent down, providing a curved contact point for the craftperson’s hand. Other indicators include evaluating the final cutting angle (angle of cutting iron + angle of bevel on bevel up planes) When there is a steep cutter angle, and the iron is bevel up, in some cases, the functional cutting angle approaches scraper territory in these short 4″ planes. In those planes, the iron was probably originally intended to be bevel down instead.

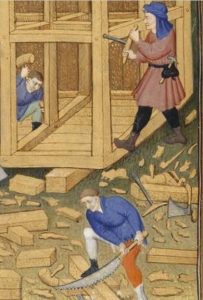

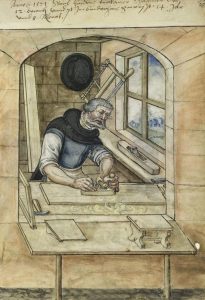

Miniature, from Book of Hours, of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. Painted c. 1407-1415. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris.

Detail from the Bedford Book of Hours, French, c. 1410-1430, showing the building of Noah’s Ark. Similar small plane on right side. British Museum.

On the left side of this small painting (c. 1407-1415) is a small plane, with thin sides, apparently metal, and of the same basic type as other examples from this period.

The iron doesn’t look to be fully installed to me, and resting on the heel of the plane. But in these paintings, it’s hard to determine.

Vergatthobel, as displayed online from the MAK in Vienna. From collection of Dr. Albert Figdor (1843-`1927)

This Vergatthobel, which resides in the Arts and Crafts Museum, in Vienna, Austria, was studied by W.L. Goodman, for his book, “Antique Woodworking Tools,” around 1960. The plane is constructed of iron stock, brazed together, and is 5″ long and 2 3/16″ wide, with a 1 3/16″ cutting iron. Goodman concluded that this plane is similar to those depicted in the two paintings shown above.

Early instrument plane, similar configuration to that of the Vergatthobel. Photo from iluthier.com, 2002.

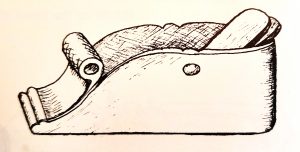

Vergatthobel (block plane) from the Kunstgerwerbemuseum in Vienna. Early 16th century. Drawing by W.L.Goodman, c. 1960.

Like other planes of this type, the body consisted of 3 sheets of iron: the single piece sole with mouth cutout; the sidewalls, bent into a “U” shape at the heel; the front piece.

The iron was set at 32 degrees, with the back of the iron resting on the rear sidewalls of the plane, and the cutting end resting on the rear edge of the mouth, which was 1 1/2″ long and 3/8″ wide.

It is not clear to me whether or not this plane was intended to have a bevel up or down iron because it has a fully flat iron. But I suspect it was intended to be bevel down. In the lower photo you can see the back of the iron, the metal wedge, and a second, smaller wooden wedge inserted between the cutting iron and the metal wedge.

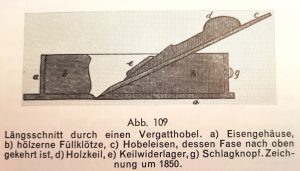

Going through at least 3 printings, in 1956, 1987, 1991, and an English translation for EAIA by Seth W. Burchard , also in 1991, “Die Geschichte des Hobels,” by J.M. Greber has been a major reference for early planemaking for many years. In general, Greber described the Vergatthobel as ranging from 20 to 30 cm. in length (8″ to 12″), with a width ranging from 5.5 to 8 cm. (~2 1/8″ to 3 1/8″). Greber described the Vergatthobel as a “special plane for endgrain edges and mitres. …with all iron construction, or at least an iron sole on wood body…with the rear cavity always filled with wood so that the blade has support.” The iron was positioned bevel up at an angle of 18 to 24 degrees.

By the 1500s, Greber wrote, the Vergatthobel was needed a lot for the intricate cabinetry that was starting to be produced at that time. But since the 19th century, according to Greber, the Vergatthobel had become eclipsed by the American block plane (Hirnholtz/endgrain plane) and was thus little known by woodworkers in the 20th century.

A number of issues are posed for the present day reader of this text. No distinction is made between the configuration or purpose of the smaller Vergatthobel, ranging from ~7 cm. to 13 cm. (2 3/4″ to 5 1/4″–my dimensions, Greber didn’t give any) despite the fact that these smaller planes were almost invariably designed with the iron to be positioned bevel down. Outside of depicting the one 4″ vergatthobel example, Greber was dismissive regarding the smaller wrought iron planes: “Smaller species only occur sporadically” (p.228). Also, Greber stated that “In England there was no corresponding plane [to the Continental Vergatthobel].” But then he included a cross-section view of a “Vergatthobel” from 1850, that was clearly a British mitre plane. And Greber also distinguished the ornate planes made by Leonhard Danner in Nuremberg in the 1560s as separate from the Vergatthobel, identifying one 5″ example as a “Schropphobel” (scrub plane) and another example as a “Schlichthobel” (simple plane).

“Schropphobel” (scrub plane) as described by Greber, and made by Leonhard Danner in Nuremberg in the 1560s. Greber, p. 220.

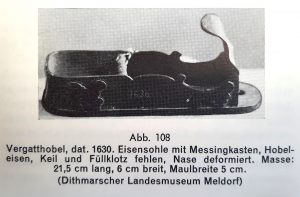

Meldorfer Vergatthobel, dated 1630, with brass or bronze body, iron sole, and deformed nose (tote bent upwards). Greber, p. 228.

“Les Rabots” was written by P. Bouillot, X. Chatellard, and J.C. Parent in 2014, and published by Editions Vial in Paris, France. This is a huge comprehensive book on mainly French planes; surrounded by hundreds of pages on wooden planes, both familiar and unheard of, are a page or so on the early Continental iron planes. The authors divided the European metal planes into three categories: 1. Wooden body/iron sole planes, with a history going back to the Roman planemakers, and also illustrated by Felibien; 2. Wrought iron planes, made of three plates, and brazed together with copper based brazing compound; 3. Cast iron planes, introduced in France by Chardoillet and others beginning in the 1840s. Two distinct types of brazed iron planes were described: the larger ranging from 20 cm. to 30 cm. long, and a smaller type, ~3 cm. to 13 cm. long, with a cutting bed angle ranging from 25 to 60 degrees (which encompassed both large and small types). The iron would rest on a bed of wood, or sometimes just the rear edge of the mouth, and the top of the curved heel:

“We can see in the collections tools whose sole protrudes from the body forwards and sometimes backwards; others whose front plate is curved forward, rolled up on itself, or open and wavy, transforming into a decorative handle. The upper edge of the cheeks is sometimes very indented. …quality between examples varies enormously.

A study which remains to be carried out could make it possible to clarify the geographical origins of these different decorations.”

In “Les Rabots,” iron planes were said to be used by all craftspeople who demanded robustness and precision from their tools: luthiers and bow makers, organ and pianomakers, cabinetmakers, and also for marquetry, as shown in Felibien (1619-1695). Screws bored from the top of the wooden plane body, secured the iron sole of the plane to the wood.

The old craftsmen had copper brazing alloys which would melt at different temperatures within an oven, enabling multi-step assembly of the iron components. In this case, we have the U-shaped body, a separate front piece, a cross-pin, and the sole. Plane has a thick stock and is more sturdy than many of this type. The wedge typically did not span the full width of the interior of the plane body. This particular plane has a cormier wood rear infill, which greatly helps to bed the iron securely. Many examples of this class of early iron ‘block’ planes do not have a rear infill, and the thin iron rests on the the precipice of a thin sole and the heel.

The old craftsmen had copper brazing alloys which would melt at different temperatures within an oven, enabling multi-step assembly of the iron components. In this case, we have the U-shaped body, a separate front piece, a cross-pin, and the sole. Plane has a thick stock and is more sturdy than many of this type. The wedge typically did not span the full width of the interior of the plane body. This particular plane has a cormier wood rear infill, which greatly helps to bed the iron securely. Many examples of this class of early iron ‘block’ planes do not have a rear infill, and the thin iron rests on the the precipice of a thin sole and the heel.

Brazed isolated dovetail in rear of plane, which actually may have started life as a tenon, before repeated hammer blows truncated the extended sole.

This Italian plane was constructed with a sole that bends up 90 degrees to form the front plate, and then back over 45 degrees to form the tote. The sidewalls are attached to the front plate with rivets joining tabs from the sidewalls bent over 90 degrees. As usual, the crosspin serving as the bridge is peined over on either side. The one piece sole is connected to the sidewalls with a pin and post method: two are placed in front of the throat on either side, and another is located at the heel. The rear infill is so old, that it shows collapsing grain, and does not appear to have been glued to the inner heel.

Some, cutting irons were very thin before c. 1780. Other 16th to 18th century blades were thicker and may be blister steel, developed around 1600, but may also be all wrought iron, with no cast steel inserts let into the business end by forge-welding, as found on blades beginning after 1750. In many examples, the far end of the cutting iron was bent hot, into a curve, or scroll. Also, many of these early irons would feature tapering sides, with the width of the top being much narrower than that of the cutting edge.

During the Medieval Period, blacksmiths had methods for case hardening the working end of iron tools, by utilizing what we now describe as nitro-carburization in a process utilizing nitrogen (dissociated ammonia), which enabled the hardening to occur at lower temperatures and shorter durations than other methods, such as direct carburization. Methods of hardening iron were described in the early Medieval text of Theophilus’ “On Divers Arts,” (pp. 93-95) likely written or compiled by a pseudonymous Benedictine Monk between 1100 and 1120. Of course, craft workers would wear through this hardened outer layer, and require repeated case hardening for their edge tools.

Some French and Italian versions of this early Continental European block plane were ornate, and featured heart and clover cutouts, and intricately shaped edges:

Early mitre planes followed, and evolved from the Vergatthobel, according to W.L. Goodman. Both the Vergatthobel and the Gehrungshobel utilized similar brazing techniques, but the mitre plane was a larger plane generally, from 8 to 12 inches long, with a bevel up cutting iron, set at a low angle, 20 to 30 degrees, usually supported by a bed made of hardwood. The sole of the early mitre plane was often thicker than that of the early block plane. Because the mitre planes were larger, and used for engaging in somewhat larger scale work, additional attachment methods were used to connect the sole to the sidewalls. In addition to the isolated dovetails found on the smaller ‘block’ planes, the mitre planes utilized tenons through the sole, and less commonly, the pin and post method. Also, the early mitres typically had a front tote. Decoratively, the mitre plane would have embellishments on the outline of their sidewalls, and feature baluster bridges.

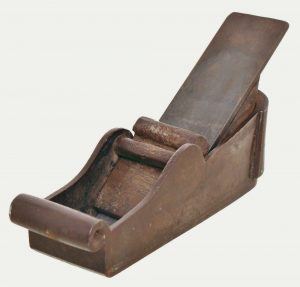

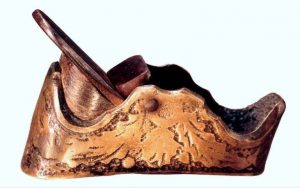

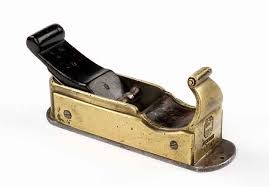

Pictured below is an early 3″ luthier plane, with the same basic profile as we have today. Back in the 17th century, circular pipe stock was not available, so an overlap join was made at the toe. Circular pipe stock only became readily available around 1840; in the 18th and early 19th centuries, however, some luthier planes were constructed with applied soles and continuous metal stock for the ovoid body.

16th to 18th century Luthier plane, with familiar form. Iron, with sidewalls joined at the toe. Photo from osta,ee in 2014.

16th to 18th century Luthier plane, with familiar form. Bevel down cutting iron. Photo from osta,ee in 2014.

16th to 18th century 3 1/4″ instrument makers plane. Wrought iron with brazed on sole. There’s a couple of capitol letters inscribed upside down on the side, looks like ‘CR.’

The following small wrought iron plane has side profiles that remind me of the mouldings at each end of the keyboard on Italian harpsichords, and may have been made in Italy as well. The sole is brazed to the sidewalls in the common method of the time; the plane was too small to require additional attachment methods.

Where Early Planemakers Worked

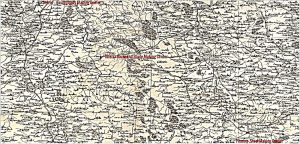

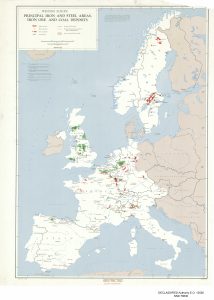

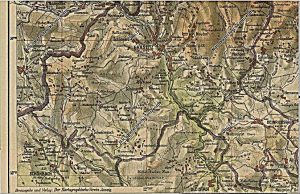

Iron, Coal, and Steel locations, from a former classified, geopolitically sensitive map, issued c. 1952

Anonymous makers of 16th to 18th century block planes, mitre planes, and luthier planes typically were located around sources of iron and early steel blade-making, with delivery access to cities and communities where there would be customers for their products. Such early centers would include Firminy and Thiers in France, Bergamo and Brescia in Italy, and Solingen and Nuremberg in Germany.

This particular map shows some overlap of early metal planemaking, and centers for iron mining and production, but it postdates the tail end of early European iron planes by a good 100 years. For example, the isolated Pyrénées region, on the border of France and Spain, was an active location for early iron mining and forging. But by 1950, this area had receded in importance for those commodities. Nevertheless, many small early French iron ‘block’ planes originated from that area.

Other locations show more congruence. For example, Bergamo, Brescia, and Milan show a large steelmaking industry present, and this is where many early iron planes and tools were made, including early instrument making planes. Nuremberg shows both iron mining and steel making, and this was a center for many early iron mitre planes, smoothers, and block planes. Austria also shows iron mining activity, and this was another center for iron planemaking. Mirecourt was located just south of Nancy, which was a center for iron mining and steel production, and this was the location of a small community of metal toolmakers providing implements for the instrument makers of the area. Solingen was just south of Dusseldorf, surrounded by many iron mines.

Although the steelmaking industry in Firminy was established in the mid-19th century, the town had producing coalmines since the 14th century, and had a history of forging iron there for centuries. Thiers, the foremost knife and blade making center in France since the 12th century, did not have its own steel, coal, or iron industry, but instead relied on nearby Firminy and other areas such as Liège in Belgium, or Solingen in Germany, for iron and steel.

Jenzat is a major center for hurdy-gurdy making, which is discussed later on this page. Firminy was formerly called Firmin. The detail on this map is hard to make out, but the authenticity of locating places on a period map makes a difference.

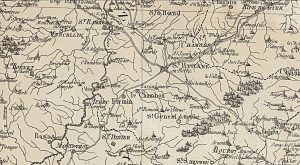

Below are close-up sections of Firminy, Thiers, and Jenzat in the Cassini Map, 1790:

This virtual tour of France shows some toolmaking locations, with an emphasis on the musical arts. Mirecourt, Jenzat, Thiers, and Firminy are touched on in this page; Villedieu-les-Poêles and Léon Pinet et Cie. of Paris are covered in other pages on this website.

More early block planes, from the 16th to 18th century, made of iron stock, brazed together in ovens

Dovetailed and brazed French block plane, probably from the Pyrenees, 4 1/4 inches long. 17th century. No. 802 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell.

These early block planes were shaped like a shoe, with the heel bent around a form, just as the mitre planes that followed were also. With this particular example, the oak wedge and curved bevel down thin cutting iron are likely original. Two isolated dovetails were placed behind either side of the mouth. A big dollop of copper brazing material was left in front of the mouth.

A previous owner bent over the toe of the plane, in order to conceal a decorative edge. This alteration is part of its history. A number of planes with a similar profile have been found in the Pyrénées region or the Pyrénées foothills.

But it must be stated, that a number of examples of early Continental iron planes from both France and Italy, if not additional countries, shared this basic shape. This common profile may have developed in different regions independently, being such a simple and natural form, or some tools may have been carried by traveling merchants between communities along established trade routes.

This 18th century Italian chariot plane was made differently, with the sidewalls made of 4 sheets of brass or bronze, over a 3″ x 1 1/4″ steel or iron sole, proud of the body. The top edges were chamfered, and the filework was well executed. Photos from David Stanley Auctions, January, 2022.

Coming from the John & Janet Wells collection, this hollow-faced early iron ‘block’ plane may have been used for making the fingerboards on the family of violin-string instruments.

Hollow faced, small French iron plane. Photo from David Stanley Auction, April, 2019. Formerly John Wells collection.

The following c. 16th century wrought iron plane shows a drawing of “a donkey on a flowered mound and a deer lying under the gaze if a man in profile holding a spear. Cruciferous globe hallmark.” The iron was bent hot into a scroll at the back. 3 3/4″ long. The photos and quote came from Ferri & Associés, Auctioneers at an auction “Le Jardin Secret de M.B.- Curiosities,” (lot 72, sold for 2,000 EUR) held at the Hotel Druout in Paris, 7 December, 2018.

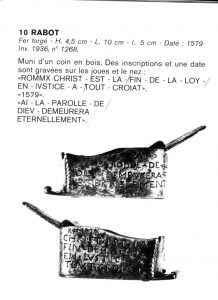

This plane dated 1579, shown below is somewhat similar in scale, profile, and by the fact that they are both engraved. It resides in The Musée Le Secq des Tournelles.

1579 French ‘block’ plane. Photo from The Musée Le Secq des Tournelles.

German block plane, front, showing lion’s head, and Musée des Arts Décoratifs et du Design Exhibition label from 1932. Photo by David Stanley, June, 2019.

Ornate German block plane, 4″ by 1 1/2″, engraved with the date 1633. Photo by David Stanley, June, 2019.

This plane sold for £10500 in David Stanley’s catalogue No 56, Lot 417 in 2010 to an American collector.

Ornate, small North Italian ‘block’ plane. This same plane from 2005 was consigned to auction recently, and it is now in my collection.

Heel of ornate, small North Italian ‘block’ plane. Here you can see the scalloped edge of the body and the collapsing grain on the wedge. Formerly from collection of Cliff Sapienza.

Interior of ornate, small North Italian ‘block’ plane. Like many other continental metal planes made before 1800, the rear infill (if present) was never glued to the body.

Early Swiss ‘chariot’ plane, 4 3/4″ long, with much later 19th century F.L. Grobet 1 1/2″ iron made in the iron and steel working town of Vallorbe, Switzerland.

Early ‘chariot’ plane, formerly in the George Gaspari collection, and shown in “Tools Rare and Ingenious,” by Sandor Nagyszalanczy, page 15. Also ex-David Russell, and currently Joel Moskowitz collection. Photo by Joel Moskowitz.

This early ‘chariot’ plane is a known, practiced pattern from the Early Modern Period (1500-1800). The example shown to the right appeared as no. 806 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell (page 277).

Shown below are two early ‘chariot planes’ that were made in this early style; they both originated from the alpine regions of Northern Italy, the Tyrolean Alps in Western Austria, and Southern Switzerland. Brazing material shows a strong copper or bronze-like color rather than a lighter brass color.

One of the examples has a 1 3/4″ iron, with a mouth that spans the entire width of the sole; the other plane has a 1 1/2″ Grobet iron, and has slightly smaller proportions overall. While the planes share the same general wrap-around construction, there are differences at the toe: the larger plane has a 90 degree bend in the sidewalls at the left side of the toe, and one brazed butt joint at the right side of the toe. The smaller plane has a separate front plate that is joined with brazed scarf joints. And the larger plane has reinforcing added to the join at the bottom of the front plate and the flange.

Observed over 20 years, the following group of planes is larger than the others, with a 1 1/2″ wide cutting iron, bevel down, and bent down over the heel. Length is 6″ and the heel is 2″ tall.

Another chariot type plane. Rare as these early planes are, distinct patterns are uncovered when enough examples are available for comparison. Photo from MJD tools, April, 2018.

Early Continental ‘chariot’ plane 6″ with a 1 1/2″ iron. Formerly John Wells Collection. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, May, 2021.

Early European Chariot plane 6″ long, with 1 1/2″ iron. This is the same example as photographed in 2003. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auctions, October, 2022. Observing the same examples of these planes that repeatedly appear over time indicates how few of them actually exist.

After decades of observing this plane, I finally picked one up myself. The photos make it look like a small plane, but it is significantly larger than the 3″ and 4″ Continental ‘block’ planes. It is a bevel down plane.

Both of the small iron planes shown below were found in the department of the Lot, in the Midi-Pyrénées region of France, and they share some similar features: 1. the bed and heel area are covered by a sheet of iron rather than being open. 2. the bridges were designed to have a screw threaded through in order to tighten and secure the wedge. 3. both planes have a front flange and rolled front tote.

16th, 17th century 3 3/4″ iron plane. From John G. Wells collection, formerly David Russell collection, no. 803. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, April 12, 2019.

Same 16th, 17th century 3 3/4″ iron plane, showing covered heel area. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions.

Early 4 1/8″ block plane, very similar. Wells collection, formerly David Russell collection, no. 801. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions 2019.

In Italy, where the following plane was found, many people have become accustomed to finding antiquities about. After all, in some areas around Rome, and other cites, 2,000 year old coins can still be found. The silver colored brazing compound looks very similar to that on no. 804 in David Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools,” and also has a similar profile from the side. Russell estimated no. 804 to have been made in the late 16th, early 17th centuries. Unlike most early Continental European ‘block’ planes, this one has a bevel up cutting iron. At the toe, the sole is folded up on itself, forming a neat lip.

Early European ‘block’ plane, found in Italy, with attractive, simple lines. 4″ long, with a 1 1/4″ bevel up cutting iron. Oak wedge shows age on it.

This Italian block plane has a thick curved iron, and what appears to be a silver or tin-based brazing compound with less capillary action than copper.

Up close, you can see the marks of the hand file. This example is in an excellent preserved state, and may have been made in the 19th century, with far earlier traditional hand techniques. Until WWII, there were a number of isolated pockets within Europe, that were not so influenced by the forces of industrialization.

Silver brazing compound melts at ~1300+ degrees F.; tin compound, ~900+ F.; brass ~1750+ F. depending on mixture of alloy.

In March, 2014, John Wells picked up this ornate Italian smoothing plane for his collection; it has an unusual squared-off heel, and the top perimeter of the sidewalls is adorned with fleur de lis like decorations. Rear infill, likely never glued to the inner heel, has seen better days. This plane is 8″ long, and 2 1/2″ wide.

Collection of 17th and 18th century Continental block planes, mostly French. The two planes on the right have baluster bridges which are not symmetrical.Photo from www.forum-outils-anciens.com

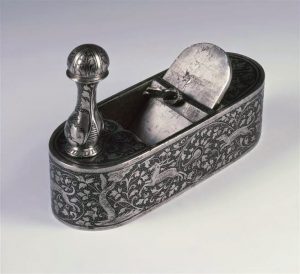

Shown below are two 5″ iron planes made by toolmaker, engineer, and artist, Leonhard Danner (1507-1585) in Nuremberg around 1570 for Kurfurst August of Saxony. The irons were positioned bevel down. Intricate etching, with hunting scenes and floral designs adorned the sidewalls, which were bent around in a long oval shape. The plane irons were fixed with thumbscrews in a fleur de lis pattern instead of a wedge, and the toes have intricately turned front totes. The toes and heels were covered under the decorated metal exterior. Images from the SKD museum, Dresden, Germany:

The photograph of this plane, with Danner features was shown in the forum Outils Anciens (Rabots) by Pierre on 16 November, 2011. It is 92 mm. long and 40mm. wide. Although it appears to lack the etching of the other examples, the form closely resembles the decorated examples found in the MAK (Vienna), SKD (Dresden), and the Musée Le Secq des Tournelles (Rouen).

W.L. Goodman had located these 2 Danner metal planes in the collection of Elector Saxony in Dresden, and a third Danner, slightly larger, at 5 1/2″ in the Arts and Crafts Museum of Vienna. A fourth example of the Danner plane was depicted in a portrait of the Nuremberg cabinetmaker, Friedrich Finkhauer, who died in 1571. While these 4 planes were custom made variants of the early ‘block’ plane, made for the elite and wealthy, they were not one-off planes. And many more less ornate, and more workmanlike examples of the Vergatthobel from this time period, survive today.

Portrait of Nuremberg Cabinetmaker, Friedrich Finkhauer, in 1571, using a similar plane. Nuremberg Municipal Library.

Early Mitre Planes

This plane, which looks like a mitre plane configuration, was stated to be from the 15th century by the Cleveland Museum of the Arts. It was acquired in 1916, as part of the collection of the the surgeon/art collector Dr. Dudley P. Allen (1852-1915) which was gifted to the Museum. Photo from the Cleveland Museum of the Arts.

Early mitre plane, 18th century or earlier, with sole extending beyond the perimeter of the plane body, and mouth aperture placed towards the middle of the sole. A similar plane was shown in Seiver’s “Il Pianoforte; Guida Pratica…” which described methods of piano manufacturing before the introduction of steam and electric power. Obviously, with an extended sole, these early mitre-type planes were not used with a shooting board on their sides. It underscores the notion that mitre planes had many uses, as described further on the piano planes page of this website.

Italian Mitre Plane, with carved fruitwood wedge, c. 1550. Provenance: Aaron Rose collection, American Heritage Museum, Sandwich Massachusetts, Laurent Adamowicz collection. Auctioneer’s estimate:$12,000-$16,000. (not sold). Photo by Skinner Auctions 2018.

Early European Mitre plane, with isolated dovetails at heel, to counter separation forces. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auctions, October, 2022.

16th to 18th century mitre plane. These early mitre planes from the European mainland were made as one-off efforts or in small quantity batches.

They were typically decorated, sometimes even ornate. This one has a bronze or brass body sweated to a thick iron two-piece sole. It was found in Germany. Typical of the style, it has a complex, turned baluster bridge, and a protruding front hold or tote. The wedge is made of cormier wood, a hardwood almost exclusively found in continental Europe. Sole is proud of the sides, and the front extension has a hang hole, which can be observed on other similar examples.

Early Continental mitres were often set up with an iron bedded closer to 30 degrees, bevel up. Part of the reason for the steep angle was to place the mouth in the middle of the plane. A long front sole and a fine mouth made the plane easier to position when approaching the edges of the wood for a cutting pass.

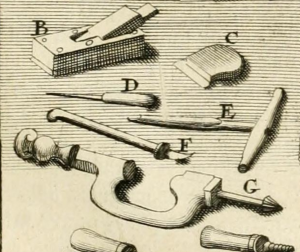

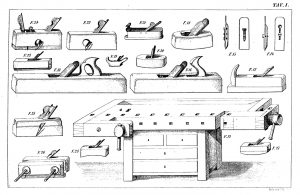

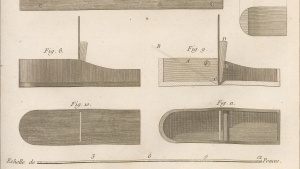

Illustrations of a workbench and a range of wooden bench planes, as shown in Siever’s “Il Pianoforte…”

In figure 21 we see a box mitre plane with a sole proud of the body, and a similar front handle to the plane shown above. Here is the key to the rest of the plate: Workbench; Bench planes: 24. fillister plane with nicker; 22. rebate plane; 18. coffin smooth plane; 17. large smoother, German/Austrian type with horn on nose; 14 English style plane iron and cap iron w/short screw;15. French/Austrian style plane iron with cap iron and long capstan screw, 23. radiused plane; 13. jointer plane; 16. jack plane; 19. Dutch gerf plane; 20. toothing plane; 25. nosing plane with double iron; 26. plow plane; 28. convex plane; 12. cabinet workbench with vises. 27. compass plane.

The following images of early continental European mitre planes are from the collection of John G. Wells, (1929-2018) prominent architect in Berkeley CA. Photos from David Stanley Auctions, April 12, 2019.

“A 17/18c European mitre plane 7 1/2″ x 2 1/4″ with extended front tote G.” Photo and quote from David Stanley Auctions, 12 April, 2019.

“A 17/18c German iron mitre plane 11″ x 3″ with decoratively shaped sides and scrolled tote (illustrated Russell fig. 795) Provenance; George Rapp collection to Allen Bates collection, ill. Tools & Trades vol 1 1983 plate 22. G.” Photo and quote from David Stanley Auctions, 12 April, 2019, lot 867.

This finely decorated mitre plane in the four photos below has a scalloped front tote in a Roman style, and a two part sole, joined by tongue and groove joints at either side of the mouth. The iron was designed to sit at 45 degrees, and the length of the sole measured 8 7/8″. Photos from David Stanley Auctions, lot 887 1 February, 2019.

“A 17/18c European iron mitre plane 7 1/2″ x 2 1/4″ with extended front tote and shaped sides. This plane is illustrated in Sandor Nagyszalanczy p 40 but has since had a replacement decorative boxwood wedge by David Brookshaw G.” Quote and photo: David Stanley Auctions, lot 873, 12 April, 2019.

“A 17/18c European mitre plane of unusually small size 5 3/4″ x 2″ with morticed sole, d/t toe and decorative sides and bar (illustrated Russell fig 799) G.” Quote and photo: David Stanley Auctions, 12 April, 2019, lot 871.

Philip Walker, the first leader of TATHS in the U.K. found this ornate mitre plane on the earthen floor of an old Southern Italian carpenters’ shop, during the early 1960s; the workshop was established in 1739. This mitre has a later cast steel/iron (cutter) made in France, with the mark of Sanborn et Cie, from Moselle, Lorraine (post 1860), and a recent beechwood rear infill marked Alberobello, with the date October 1962. This plane was probably made in Italy, but conceivably could have been transported from France, or the Tyrolean Alps in western Austria. 9 11/16″ long, with a 1 7/8″ blade. Provenance: Philip Walker, MacAlister, Alan Bates, and David Russell collections (no. 794).

This early European mitre plane, dating from the ancient regime, measuring 11 3/4″ long and 2 7/8″ wide, and shown below, was found in France. The front tote has an “S” stamped into the iron, probably a maker’s mark. At the heel, the sidewalls have been doubled on the inside. And the iron has a crown mark, with what appears to be “Perum” below that. The wedge and infill bed have been replaced.

Small mitre plane, from the Colonial Williamsburg collection: 5 5/8″ long, 1 3/4″ wide, with a 1 1/4″ cutting iron, bedded at 25 degrees.

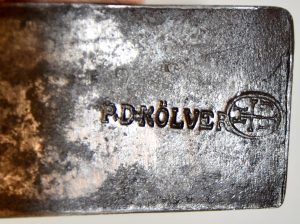

Here is a smaller 6 1/2″ mitre plane made in Nuremberg; it was sold in David Stanley’s Auction twice, and was said to have come from a German musical instrument maker’s shop. The wood appears to be original, and is probably cormier. Stamped on the tote is an unusual symbol.

The reverse “R” in the cyrillic alphabet means “me” or “I” in Russian. This may or may not apply to the tool shown here. There are many ties between Germany and Russia, then and now.

Hole on front flange of small German mitre plane, started very small and enlarged with files. Not perfectly round.

The following Continental mitre plane with a sole measuring 8″ long x 2 3/16″ wide, was reported to be Flemish; it has the typical early Continental mitre plane features in the lines of the sidewalls, with an additional flourish at the heel. The sole is attached to the body with through-tenons and brazing. On the long tote, is the letter “R,” but not reversed, as in the previous example. Like some other 18th century (and earlier) metal planes, the rear infill is held in place by pressure from the driven wedge, and is not glued into place. No evidence of hide glue fragments were present. Both the wedge and rear infill have a ridged surface, showing collapsing grain, which is evident on wood pieces older than 250 years. A baluster bridge in iron holds the wedge and iron, which appears to be original, with no cast steel lamination.

Bottom of Anderson mitre, showing the through-tenons. This laborious method of construction was practiced after the earlier method of brazing iron components together in ovens. Note the fine mouth, which is placed near the middle of the sole: its an important feature which affects cutting characteristics.

!7th to 18th century mitre plane, with front infill and no tote at the toe. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions April 2018.

“A 16/17c European mitre plane 9″ x 2 1/2″ with shapely protruding front tote and chamfered sides with all round protruding sole (illustrated Sandor Nagyszalalczy p40) G.” Quote and photo from David Stanley Auctions, 12 April, 2019, lot 891.

Frontal view, showing acanthus leaf hold. 16th to 18th century mitre plane, wrought iron. Photo from Jim Bode Tools.

16th to 18th century mitre plane, wrought iron. Downward pressure from the driven wedge forced a separation of the sole, which was repaired by additional brazing. Photo from Jim Bode Tools.

The mitre plane above was photographed by David Stanley Auctions in October, 2022. The lack of a front tote, or baluster shaped bridge, and the addition of a front infill suggest that this could possibly be an early English mitre plane.

17th century mitre plane, 8 3/4″ long and 2 5/8″ wide. 2 1/8″ replacement iron by Sorby. Photo by Jim Bode.

Early 16th or 17th century iron mitre plane, 7 1/2″ long, with 1 7/8″ iron. Ornamental replacement wedge. Photo by Jim Bode.

Small 5 3/4″ 17th century gunmetal mitre plane. Plane has a 1 1/4″ iron by G. Luckhaus. Photo by Jim Bode Tools.

The following Continental European plane is currently part of the online collection at the MAK in Vienna Austria, and it is 26 cm. long, and 5.7 cm. wide. The elaborately carved head decoration on the wedge was made out of boxwood. Greber also included this example in his 1956 book “Die Geschicht Des Hobels,” and it was donated to the MAK by Dr Albert Figdor (1843-1927).

Early bronze mitre plane. Dated 1739 and was the earliest known mitre plane that was made in England.

Most early mitre planes were made in Continental Europe: Germany, France, Austria, and Italy. This example is possibly unique, in that it it may be the only English mitre with Continental features. Features include turned baluster bridge, curved front handle, and curved sides towards the front. Sold at David Stanley 2012 auction for 7,500 GBP.

Philip Walker, the first leader of TATHS in the U.K., wrote about this plane in the first TATHS Journal in 1983:

‘[The BGH mitre] plane measures 7 inches x 2 1/16 inches. It stands 2 7/8 inches at the height of the scrolled fore-grip, and the sides reach a height of 13/8 inches measured from the sole plate. The sole plate itself is 3/16 inches thick. There is a small hole bored through the front of the sole, ‘the toe,’ a feature to be seen in Pl. 22 and on some other examples and which presumably served for hanging the tool up.

The cutter is exactly 1 1/2 inches wide, set at about 30°, and is stamped IOHN GREEN which was the recorded mark of Hannah Green 8: Son in Sheffield from 1781 to 1800 (W.L. Goodman British Planemakers from 1700 2nd edition 1978). It is likely that there was in fact a John Green working earlier than these dates but, of course. there is the possibility that the cutter is not original. a possibility made more likely by the fact that this cutter has its bevel on the opposite side to the trade-mark while it has to be set bevel uppermost in order to clear the very narrow mouth. The plane is made of copper-alloy plates, the original `box’ having a grey/green patina (a bronze?) whilst the plates added on either side are much more yellow (a brass?). These side plates box stood within the perimeter of the sole, they were probably added to enable the plane to be used on its side on a flat surface and thus shoot a joint at an automatic 90° to the horizontal. A comparable plane in the Dithmarsch Museum in Meldorf, dated 1630, has side attachments which could serve the same purpose.

The front plate, the most noteworthy feature, forms a double curve and terminates in a scroll. The scroll is shaped in the solid metal, not bent. lt was probably cast, with some tiling or chasing to finish. The plate bears three inscriptions. There is an embossed device. within an octagonal depression, of a plane (very similar to the object itself] surmounted by a wide~open pair of compasses, and surrounded by what appears to be foliate decoration. Beneath the plane are the initials BHG or, just possibly BMG. Below this device is another sunk and embossed mark: LONDON. At the very bottom of the plate, close to the internal angle formed by the meeting with the sole, and where it would have been extremely difficult to engrave anything after the plane had been assembled, is the date 1739. All or any of these marks could probably have been Cast with the front plate itself, or the date could have been engraved, but at least the ‘LONDON’ and the ‘l739′ look as though they have been punched.

Unique and fascinating as they are, these marks invite scepticism. Marks may be

added to tools for a variety of motives, some innocent some fraudulent. Town names as well as dates have been used as trade-marks or quality marks on tools made in other towns at other periods. However it is my opinion that these marks mean exactly what they say: that this plane (probably one of a series) was made by a maker whose initials were BHG, in London, in or soon after 1739. Each piece of wood, the wedge and the two filling blocks in the box, have been stamped ‘G’, so the speculation inevitably arises whether there might be a family connection with the BHG and the John Green.The cross-bar appears to be cast iron. It is of a cupid-bow baluster form, with a flat

undersurface against which the wedge bears. Bars of this type are found in…almost every other ‘continental’ mitre plane known to me. There is also some indication that the plane in PI. 27 was originally fitted with a similar bar.This 1739 BHG plane is understood to have been in the Portsmouth Dockyard

workshops for many years, and it has until recently been kept for nasty jobs where

the workmen feared damaging their personal tools. To sum up: we appear to have

here the earliest known English box-construction plane, the forerunner of all those

finely constructed planes which constituted the pride of the nineteenth century

joiner/cabinet-maker’s kit. It shares certain characteristics with a considerable series of earlier continental European planes. Whilst the date sequence does not actually prove that the English planes were derived from continental models, this plane is one more piece of evidence for the existence of a common European tradition in tool design.”

Photos below by Jim Bode.

At some later date, it appears like an owner of this plane doubled the sides of this plane, in order to make the sides flush with the sole, for the purpose of using the plane on its side. Early cutting iron by John Green.

16th to 18th Century Luthier Planes

Compassed iron plane 92mm., used and owned by Antonio Stradivari. One of several of this type in his possession. Photo from Guy Harrison.

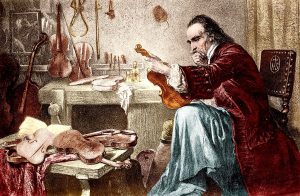

Antonio Stradivari( c. 1644 – 18 December 1737), in his Cremona Workshop. Pen and ink sketch, c. 19th century; color added later.

Two luthier planes, 50 and 58 mm. long (2″ and 2 3/8″), made from bronze castings, from the workshop of Antonio Stradivari. Photo from Maestronet Forum 19 May, 2011.

In the late 18th century an Italian violin collector, Count Cozio (1755-1840), purchased a good portion of Antonio Stradivari’s tools from his workshop. These tools eventually ended up in the Museo del Violino (Museo Stradivariano), where they presently reside. At least 4 wrought iron planes and 2 bronze planes survived from this workshop, according to W.L Goodman, who visited the museum in 1961. Inge Kjemtrup, in a 2017 article in Strings Magazine, wrote about the contribution of Count Cozio:

Cozio revered Stradivari. His passion for the Cremonese master’s instruments inspired him to seek them out from sources all over Italy and beyond, and even, in an extraordinary act for the time, to buy the contents of Stradivari’s workshop from his son, Paolo. Today those contents—patterns, sketches, notes, labels, an array of tools—are in the Museo Stradivariano in Cremona.

Four planes of Antonio Stradivari, made of wrought iron sheets, brazed together, ranging in size from 79 to 92 mm. long (3 1/8″ to 3 5/8″). Photo from Maestronet Forum 19 May, 2011.

Top view of one of Stradivari’s small bronze luthier planes. Photo from Maestronet Forum 19 May, 2011.

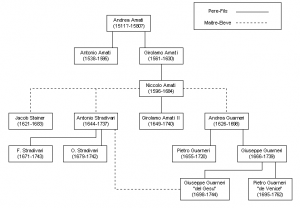

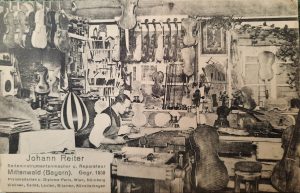

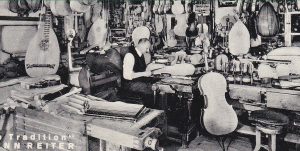

Violin making originated in Northern Italy, with earliest examples depicted in period paintings around 1530. In the beginning, with the Amati family, the craft was carried out in small family workshops, with the father teaching his sons the craft. Later, in the late 18th, early 19th centuries, in Mirecourt, France, Mittenwald, Bavaria, Markneukirchen/Klingenthal, Saxony, and Grazlitz/Schonbach, Bohemia, high volume workshops emerged, producing what are known as trade violins. In some places, such as Bohemia (currently part of the Czech Republic), much work was outsourced as piecework to members of the local communities. In other towns, such as Mirecourt, the workshops were more centralized, employing as many as 600 workers in the Didier Nicolas l’aîné manufactory in the late 19th century. The other large Mirecourt violin making factories were Jerome Thibouville-Lamy (J.T.L.), Laberte-Humbert frères/Laberte Magnie, and Couesnon.

The United States among other regions, was a big market for these trade violins. All along, the very small and medium sized workshops co-existed with with these large operations, and these small traditional family workshops tended to custom build the finer violins, violas, ‘cellos, and double basses.

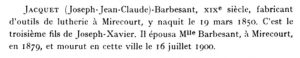

Gouged violin back. Photo by Derek Roberts.

By the second half of the 19th century, in Mirecourt, the Violin business had grown so large that the community of craftsmen in the workshops could support specialists for the trade, such as hand tool makers. One such specialist was Joseph Jacquet (not to be confused with the Jacquot family of violin makers). Joseph Jacquet was born into an instrument making family; his father Joseph-Xavier (1810-1867) and his brother Joseph-Gabriel (1848-1899) both made double basses, and in his early working life, Joseph-Jean-Claude also made contrabasses. Additionally, Joseph-Jean-Claude was known as a “Tourneur,” or Turner, and this probably was on a metal lathe for toolmaking, but could also have been turning in wood. Joseph-Jean-Claude’s wife Justine Mathilde Barbesant was a luthier in her own right, and was born into the large Barbesant instrument making family in Mirecourt. Their son, Frederic Marie Joseph Jacquet (1898-1980) not surprisingly, took after his parents, and became a luthier as well.

“Jacquet (Joseph-Jean-Claude) Barbesant, 19th century manufacturer of luthier tools in Mirecourt, was born there on March 19, 1850. He is the third son of Joseph-Xavier. He married Miss [Justine Mathilde] Barbesant [1861-1949], in Mirecourt in 1879, and died in this city on July 16, 1900.”

Stradivarius viola. Photo from Newsweek.

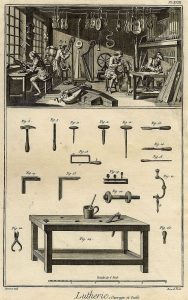

Diderot, volume 5, plate 18. “Music instrument making, works and tools.” Circa 1767, Picture includes violins, violas, a clamped up bass, harps, organ pipes, a 17th century guitar, a lute, virginal, and hurdy gurdy. A luthier is working on the face of a violin or viola, with a hand plane.

Early and ornate 16th to 17th century instrument plane, with a handcut screw through the bridge (head broken off). Jim Bode tools.

Early luthier plane, early brazed iron construction. Photo from Les outils anciens, collection Michel Mailhot.

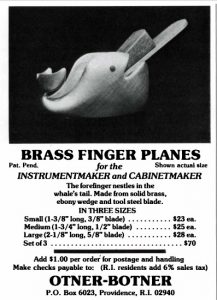

Instrument Makers Planes: 1700 to Present

Construction of the earliest metal instrument makers’ planes closely followed that of the 4″ Vergratthobel from the late Medieval Period, with brazed together iron components, with the possible exception of steel for the cutting iron, in some examples. Other construction methods followed, and I will show some of them here.

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

The first and obvious alternative would be wood construction. Wood moves with humidity and dryness, and that has been found to be less than ideal in a plane with such small dimensions. Nevertheless, Japanese makers produce tiny wooden luthier planes today.

The antique English wooden luthier plane shown below, is 1 1/2″ long, with a 3/4″ iron. A brass soleplate at the toe, closes down the mouth nicely (and counters intense focused wear at this point), and chamfers along the bottom of the cheeks give more clearance when hollowing tops and backs.

After the late 1600s, a very limited amount of iron, brass, and bronze became available in in circular, or continuous stock. This would then be cut into sections high enough for the sidewall stock of luthier planes, and then be compressed carefully, to form the familiar ovoid shape we recognise in instrument planes. Then, the sole would be brazed on, and the remaining pieces added.

Early 19th century French Luthier plane, 2 3/8″ long with brazed-on sole. From collection of Janet Wells; photo from D. Stanley Auctions, February, 2019.

You can see the join all around the perimeter of this Luthier plane. Joining the sidewalls to the top of the sole was the most common applied-sole method used for instrument makers’s planes. And the simplest.

The late Janet Wells, wife of noted Berkeley architect, antique tool collector, and author, John Wells (1929-2018) had her own collection of instrument makers’ planes that was separate from John and Janet’s joint tool collection. Janet Wells found this Luthier plane in the famous Brimfield Flea Market in Massachusetts in 1982.

Early 19th century French Violin plane, with applied compassed and radiused sole. Photo by D. Stanley Auctions, February, 2019.

This French Luthier plane shown below is of a similar type to that shown above. Copper brazing compound looks very much like that from the early European 3″ and 4″ iron planes that were introduced in the late medieval period. French Luthier planes with applied soles like this were made from the 17th century, extending all the way into the early 20th century.

French Luthier plane, made of iron, with applied arched sole. Join filled with copper-based brazing compound.

French Luthier plane, made of iron, with applied sole. Capillary spread of copper brazing compound on inside of toe.

The Russian toolmaker who built this plane did not skimp on the copper-based brazing compound during assembly. Exterior of the body was cleaned up, but the interior was left as-is, after compressing the copper alloy with a convex mould before solidifying.

Many Russian violinists play instruments made in Italy, France, and Germany, but in the 19th century, a number of Central and Western European luthiers emigrated to Russia, adding to a modest number of native born luthiers. Some notable Russian luthiers would include Robert Ivanovich Arkusen (1844-1920), Ivan A. Batov (1767-1841), V.V. Ivanoff (1850- ), Nikolai Kittel (1805-1868), Ivan Krasnocheckov (1798-1877), Anotoly Leman (1859-1913), and Eugen Vitichek (1908-1943).

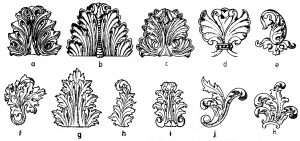

Timeline of acanthus styles: a) Greek; b) Roman; c) Byzantine; d) Romanesque; e & f) Gothic; g) Renaissance; h & i) Baroque; j & k) Rococo. From wikipedia.

The use of curved embellishments on the toe of some early luthier planes sometimes took the form of an acanthus leaf, which has been used in art and architecture since the Greek Classical Period: most notably, in the capitols of Composite and Corinthian columns. Acanthus leaves as a decorative form were also used on some elaborate French and Italian mitre planes, as shown earlier on this page.

Set of three 17th/18th century French or Italian luthier planes, with rear infills, scrolled rosewood wedges, flat bridges and ornate acanthus leafs (with 7 and 9 fronds respectively) or scroll at the toes. They range in length from 1 1/4″, 2 1/8″, and 2 5/8″, with 9/16″, 7/8″, and 1″ toothed irons. The shortest and longest ones have arched soles.

Sometimes the applied sole was reinforced with isolated dovetails, usually added at the toe or heel. Wood clamp came from C.C. Hornung Piano Factory, San Francisco.

This set of 17th/18th century luthier planes was made before circular metal stock was generally available. In this case, the brass was brazed together at the heel, and strengthened by pinning into the rear infill.

The applied soles of these planes reveal more on their construction, showing pinning into the rear infills, with dovetails at the toe on two planes. This angle also shows another view of the two acanthus leaves as well as the small scroll in the middle. The brass stock shows an uneven texture, which may have been due to oxidation over the years, or may have been a result from early manufacturing techniques.

These seven 17th, 18th century luthier planes have a similar form as the set of three shown above. In the two photos directly below, the two planes on the right side, appeared in “The Art of Fine Tools,” by Sandor Nagyszalanczy, page 195. Published 1998.

Seven 17th, 18th century luthier planes. From 1 1/4″ long, to 4 1/4″ long. Photo from Jim.Bode, c. 2018.

The inset sole is much less common, and more difficult to make. This particular sole was slightly rounded both ways: radiused and compassed. It was done to reduce the thickness of the spruce soundboard and maple (or other hardwoods) back, which were made crowned, or convex on the outside. This was done to optimize strength while also being very thin, which increased vibrational properties, and projection of sound. The compassed and radiused sole of many luthier planes, was ideal for working the inside of these two plates, which were concave. Rounded soles, however, could also be used on the outside of these components.

Coopers also used compassed and radiused planes for working the inside of barrels, which were arched to enhance strength and lightness. These were called Coopers’ Stoup planes

Dovetailed brass Luthier plane, rosewood infill, 1 1/2″ long. Curved tote at toe; exposed infill at heel. Photo by David Barron, 2014.

Another method of constructing luthier planes is by using multiple dovetails, which is almost unheard of, however. In 2014, David Barron posted some photos of a beautiful antique 1 1/2″ violin plane, probably English. At this small size, multiple dovetailing could be considered overkill.

During March 2023, David Barron sold his dovetailed violinmakers’ plane with skewed iron on Ebay, and for the sale, he took the following photographs:

Investment casting, or lost wax casting goes back 5,000 years, and was also used on some early instrument planes. The antique French violin plane below was most likely investment cast.

Engraved gunmetal luthier plane, late 18th, early 19th century, with iron wedge and applied sole. 2″ long; 1″ wide. Originally found in an antique shop across the street from the Louvre Museum in Paris in the 1970s. From Janet Wells collection. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, April 2019.

Engraved gunmetal luthier plane, with iron marked F. Ferry Mirecourt. The Ferry family was a large instrument making family in Mirecourt throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Internal cleavage on toe. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, April, 2019.

Engraved gunmetal luthier plane, with Fleur de Lis engraved on heel. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, April, 2019.

Engraved gunmetal luthier plane, showing sole. Investment casting. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, April, 2019

Because the form of the ‘modern’ luthier plane is over 250 years old, it is sometimes difficult to estimate the age of these small planes. Janet and John Wells concluded that this plane dated from the 17th century. I didn’t think it was that old, but thought that the engraving suggested late 18th/early 19th centuries. That still may be true, but the cutting iron with the Ferry stamp (which could have been added later) belonged to that of Francois Ferry, of Mirecourt, a “tool maker whose mark we find on real, highly sought-after jewels,” according to luthier Roland Terrier. Born into the large Ferry instrument making family in Mirecourt, Francois Ferry (1889-1942) was known as a mechanic fitter and manufacturer of violin-making tools.

8 Quai Clasquine Mirecourt. Francois Ferry (1889-1942) Son of a railway employee and nephew of two luthiers sets up as a mechanic fitter and manufacturer of violin -making tools.

Francois Ferry married Charlotte Julie Monginot (1894-1940) on 7 October, 1913. They had no children.

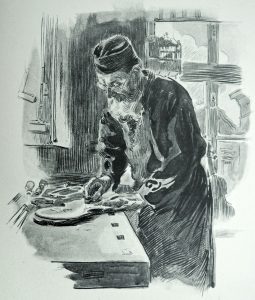

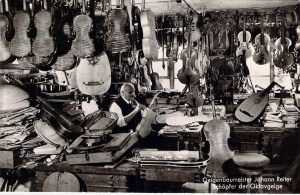

Like the luthiers’ tools themselves, Francois Ferry’s Mirecourt Workshop had a timeless quality about it. A craftsperson could have plied their trade there in 1940, or 1640.

Use of a baluster bridge was another design element that could be found on some 17th and 18th century luthier planes as well as mitre planes.

Brass Violin plane, 2 1/4″ long, and 1 1/4″ wide, showing right side. Rosewood wedge. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions February, 2019.

Brass Violin plane, 2 1/4″ long, and 1 1/4″ wide. Compassed and radiused applied sole. Janet Wells collection. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions February, 2019.

Brass Violin plane, 2 1/4″ long, and 1 1/4″ wide. Compassed and radiused applied sole. Janet Wells collection. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions February, 2019.

18th Century luthier plane, with baluster bridge, applied sole, and parted toe. From collection of Janet Wells. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, February, 2019.

18th Century Luthier plane, left side. 2 1/4″ long; 1 1/4″ wide. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, February, 2019.

18th Century Luthier plane, showing face, or sole. Auctioneer’s estimate was £200-£300, relatively modest for such a fine tool. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, February, 2019.

18th Century Violin plane, disassembled, showing rear infill. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions February, 2019.

Same line-up of violin planes, but in reversed order. Investment castings. Plane on right with parted toe, and hand-cut teeth on iron.

Set of four late 18th, early 19th centuries violin planes, with baluster bridges, and similar wedges: 2 3/16″ rounded; 2 1/8″ flat; 1 3/4″ flat; 1 3/4″ rounded.

Real or Counterfeit?

After publishing these images of the set of violin planes with the ornate bridges, I was contacted by an English collector who informed me that bridges for small planes had been made from early iron skeleton keys by an antique tool dealer and auctioneer (now deceased). Furthermore, there was no information, or qualification regarding the issue that the planes were not authentically from the 18th century at the time they were introduced to the public. When the plane shown below appeared, I was fully convinced that these were fakes:

Luthier plane, c. 1900, with later baluster bridge, and peined over crosspin on either side of the cheek flanges.

Antique Violin plane, with Baluster bridge, ebony infills, ebony wedge, arched sole, and curved, toothed iron.

I now have five of these violin planes, and can see some distinct patterns that apply to most of them.

- Ebony wedges, all in the same pattern (1 rosewood).

- Toothing irons, of the same maker’s pattern in 4 of 5.

- Baluster bridges; 3 from antique skeleton keys; 1 brass, prob.20th century; 1 brass, possibly authentic.

- Plane castings ranging approximately circa 1880 to 1930.

One of the plane castings–probably the oldest of the imitations–was made of solid bronze with a parted toe. It was the only plane not to have one of the late 20th century toothing irons; it had a Sheffield iron with a mark from the 1870s.

These five planes came from three sources: England, Canada, and the United States. Only one seller represented these planes as “probably 18th century.” The other two sellers made no claims regarding the age or authenticity of the planes. One of the sellers stated that he had owned one of these planes for around 25 years. That makes sense to me, because the economics for the current value of these planes, $80 to $120, would not justify the cost of materials, and also the labor, which was not insignificant. Drilling out the ‘fake’ bridge, filing it on the bottom, and fitting it to the plane would have involved some careful work. Then there was the matter of making the wedges out of ebony from scratch. It would also have taken some time to source 100 year old donor violin planes. And the percentage of antique keys that have the correct ornamentation, and the required length on either side of that is very small. The few keys that would work range in age from the 1600s, to the Victorian period in the 19th century (also coming at a price). Toothing irons are not cheap either, starting around $25. In the case of the last plane shown here, two ebony infills were also fitted, in addition to the matching ebony wedge.

Ornate Instrument Makers’ plane, 1847; #1007 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell. Photo from Jim Bode, c. 2016.

Being in the business, the antique tool dealer who was responsible for releasing these planes to the public, would have had access to an intermittent supply of old luthier planes, and probably some old (very) iron skeleton keys as well. Even so, it would seem to me, that given these costs, a price of around $250 per plane (in today’s dollars) would be needed to break even on the materials and labor invested. Of course, in the 1990s, antique tool prices were higher generally.

Ironically, some of the antique keys were likely as old as the actual baluster bridges in planes from the 18th century. The last dated baluster bridge that I’ve found on a luthier plane was from 1847.

I think that the 2 3/16″ violin plane with arched sole and rosewood wedge is possibly authentic, and served as a template for the series of imitations. The rosewood wedge shows some age on it, and the pattern of the bridge is identical to that found on period luthier and mitre planes.

Three vintage luthier planes, l. with turned bridge; m. with portion of brass handle; r. with antique English skeleton key segment. All bored completely through.

Some time later, I found some old rough bronze castings of some violin planes that never had anything done to them after leaving the foundry. With the experience described above, I decided to finish off these planes myself, with decorative bridges.

The two luthier planes on the left have African Blackwood wedges, and the plane on the right has a wedge and infill made from snakewood, which is used for the bows of some Baroque string players.

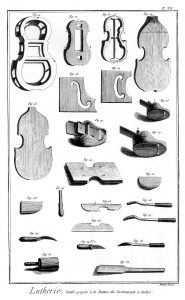

Diderot, volume 5, plate showing stringed instrument components and three ovoid shaped violin planes. By the 1760s, luthier planes had developed into the basic design that is still used today.

The image of a luthier plane in Diderot’s plate shown here shows a compassed and radiused sole, and a parted toe, which was a decorative element in some European luthier planes from the early 1700s to about 1900.

Some books on violin-making, published at the turn of the 20th century still showed some luthier planes with the parted toe.

Drawing of a side view and cross-section of violin planes, and a frontal view, showing parted toe. From Violins and Other Stringed Instruments,” by Paul N. Hasluck, 1907.

Drawing of Violin planes with toothing iron, radiused and compassed, and parted toe. From “Violin Making, as it Is and Was,” by Edward Heron Allen, 1907 (original drawing appeared in 1882).

The French Evano violin plane (below) was made of pressed steel, which, if you stretch the rules a bit, could be considered yet another method for constructing violin planes. Evano luthier planes were probably made, circa 1900-1940.

Two Evano pressed steel violin planes, and Five Classic style antique French Violin planes. Photo from French auction, c. 2016.

Evano Violin Plane, showing adjustment screw at heel, which tips the frog, and changes both the cutting angle as well as the size of the mouth. Photo from Jim Bode, 2016.

In a French forum, Outils Ancien, an observer stated that the Evano plane was really a scraper, intended for scraping off glued down paper labels, and that it is not a plane for luthiers. The jury is still out on that, I believe.

Last but not least, we have an instrument makers’ plane in German Silver, probably dating from the late 19th, early 20th centuries.

German Silver Instrument Makers’ plane, with ebony wedge. Peining the crosspin in this manner was an old practice.

–Not sure what V.C. stood for. It could have been the maker’s initials, or it could have stood for violincello.

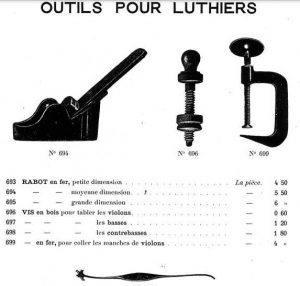

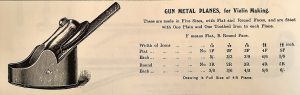

693. Violinmakers’ planes in iron, in three sizes: small, medium, and large.

696-698 Wooden screws for clamping the table [soundboard] of violins/cellos/contrabasses.

699. Iron clamp, for gluing violin necks.

Soundpost adjusting tool.

French Bowmakers’ Planes

Bowmaking is a specialty which requires the full concentration of the craftsperson, and those who ply this trade, make only bows, and not instruments. It was not always a separate profession, however; in Mirecourt, the archetiers’ field advanced to the point in the late 18th century, where specialization became standard practice.

The bowmakers’ plane shown below, often had a toothing iron, just like many instrument planes, to cut across the grain of difficult hardwoods, such as pernambuco and snakewood, used for making bows.

Similar in form to the early continental mitre plane, the bowmakers’ plane could be considered a scaled down version of the early mitres, with a bevel up cutting iron. The bowmakers’ plane featured a scroll tote at the toe, and a doubled, or reinforced heel. Made in limited quantities, the bowmakers’ plane is still made in small specialist workshops to the present day.

Bow makers plane, large at 6″ length, with 1 1/16″ iron. Reinforced heel, mahogany wedge, and cast body.

This mitre plane pictured below is similar to the bowmakers’ plane in its configuration, but was used by hurdy-gurdy makers in Jenzat, France. Hurdy-Gurdys used a crank that turned a rosined wheel against the strings to create the sound. Here is description of the hurdy-gurdy from wikipedia:

Melodies are played on a keyboard that presses tangents—small wedges, typically made of wood—against one or more of the strings to change their pitch. Like most other acoustic stringed instruments, it has a sound board and hollow cavity to make the vibration of the strings audible.

Most hurdy-gurdies have multiple drone strings, which give a constant pitch accompaniment to the melody, resulting in a sound similar to that of bagpipes. For this reason, the hurdy-gurdy is often used interchangeably or along with bagpipes. It is mostly used in Occitan, Aragonese, Cajun French, Asturian, Cantabrian, Galician, Hungarian, and Slavic folk music.

One or more of the drone strings usually passes over a loose bridge that can be made to produce a distinctive percussive buzzing sound as the player turns the wheel.

Large, heavy 18th century low angle instrument makers plane, 8 3/8″ long and 2 1/8″ wide, with double crest on sidewalls. Later I & H Sorby iron, with ash wedge, probably original. Rear infill is shimmed with thick papers full of very old French script.

Body is made of thick wrought iron stock, a 1/4″ sole, which turns up 90 degrees at the front, forming the toe plate; all brazed together, with pillar and pin construction. Formerly in Russell collection, no. 810. Found in Allier area of France, which includes the town of Jenzat: a center for hurdy-gurdy making. Famous hurdy-gurdy makers there include Pajot, Tixier, Pimpard, Decante, and Nigout.

Hurdy Gurdy made by Pajot, Allier, France. Circa 1880s. Photo from http://www.music-treasures.com/antmisc.htm

Rear view of planes, showing reinforced heels, Foreground: doubled on the interior. Background: doubled on the exterior.

Jean-François Chassaing from http://maison-luthier-jenzat.fr/le-musee/ on the instrument making town of Jenzat:

The instrument-making centre of Jenzat draws the attention of musicologists because of the high quality of the work, and the makers’ specialization in a single instrument, namely the hurdy-gurdy. This heritage has long since aroused the interest of museums.

In 1959, Mr. Favière, the curator of the Bourges Museum, wished to set up two glass-cabinets devoted to hurdy-gurdies in the Montluçon Museum; to do so, he requested the aid of Mr. J.-A. Pajot, Maison Pajot Jeune at Jenzat.

As early as 1960, an important collection had already been made by the Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaires in Paris, as a result of several visits Georges-Henri Rivière, the curator of the museum, had paid to Mr. Pajot, and of the inquiries made in 1959 by two MNATP musicologists, Claudie Marcel-Dubois and Marguerite Pichonnet-Andral, research workers at the CNRS.

In 1984, an exhibition prefiguring the Jenzat Museum was financed by the Mission du Patrimoine Ethnologique of the Ministère de la Culture. In 1986, the foundation of the Maison du Luthier-Musée allowed the acquisition of a very important collection of tools (see the hurdy-gurdy workshop), through a donation by Jacques and Hélène Pajot, and as a consequence of the inquiries (1983-1984) made by Jean-François Chassaing, an ethnologist.

In 1991, the city of Montluçon bought a collection of tools from Mr. Boudet, an instrument maker, for its own museum ; originally, these tools were part of the Pajot Jeune collection.

From “L’ Art Du Menuisier,” by Andre’ Jacob Roubo. Paris 1774. Plate 281. Similar metal plane. Vertical position for toothing iron, and alternative ~30 degree angle for a bevel up iron.

After 1935, the major part of the tools for musical instrument making belonged to the Maison Pajot Jeune, for at the time their workshop was the last one still in operation in Jenzat. From 1991 on, the collections have been shared out among the museums of Paris (MNATP), Montluçon and Jenzat. The tools have been shuffled and reshuffled and dealt out, some coming from the Pimpard workshop, some from the Nigout workshop, others from the Tixier workshop, others again from the J.-B. Pajot workshop. Only a close study of the various items can result in finding out the identity of their original owners.

The Jenzat Museum has started research in this field, as well as in others concerning the circulation of hurdy-gurdies, the trade and restoration of the instruments, the use of certain specific tools, such as the Keyboard-rulers.

Antique Palm Planes

The ‘ears,’ form the flanges that hold the cross pin, and the void behind them leaves the iron exposed, with room to move the blade side to side. In the example below, however, there is a small second ‘hump’ which adds embellishment to the side profile of the plane. The carved woodwork looks Italianate to me, but could also be French.

Large instrument plane with double crested sidewalls,, probably early 19th century. Iluthier.com c 2005.

Another instrument maker’s plane with double crested sidewalls for large stringed instruments, in a very old style, and slightly compassed cello and bass maker’s plane with applied sole.

3″ Palm plane, double crest on sidewalls, with stamp of B. Steffen Berlin, on cutting iron. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, 2015.

These three palm planes appear to have the same casting as the plane with the mark, B. Steffen, Berlin on the cutting iron. I have searched German records for a Bruno, Benjamin, or Bernhard Steffen in Berlin, who had some relation to instrument making (or leather working), but have not had certain confirmation around finding the possible maker or seller of these planes.

B. Steffen, listed under “Werkzeuge” (tools/toolmakers) in the Berlin City Directory for 1953, which seems late for these palm planes.

The plane with the beech wedge appears to be almost identical the the one in the 2015 Stanley Auction. On the toe of the other two palm planes are finger rests, one in rosewood, and the other in brass. The brass piece appears to be a factory part. Over the last 20 years, I have probably seen about a dozen of these German palm planes, and in that time have acquired these three examples. While I suspect these planes date from c. 1885 to 1935, I think the double crest decoration is an earlier decorative element, as shown on the 18th century Hurdy-Gurdy luthiers’ plane shown earlier, and in the c. 2005 photo from iluthier.com (defunct).

Real or Counterfeit?

Large 3″ Luthier plane, with many similar features to the German planes shown above. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auctions.

In October 2022, this 3″ plane appeared in the Brown Antique Tool Auction and was described as made in the 17th or 18th century . It has the same size and profile in the back half as the German planes shown above. It even has the same wedge as the B. Steffen plane and the basic model shown in my set of these planes. The double crest on the sides was continued all along the front of the plane, never exceeding what would have been available to work originally.

Caveat emptor.

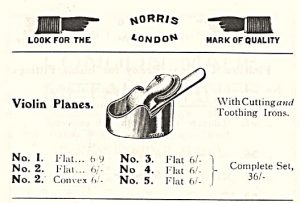

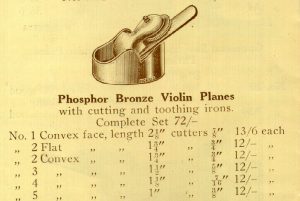

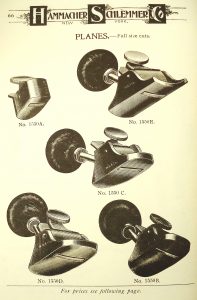

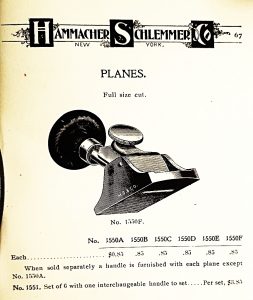

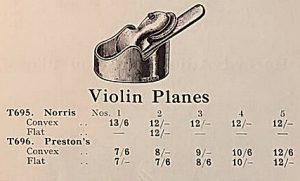

Preston and Norris Violin Planes

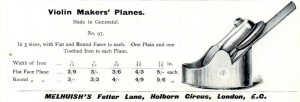

Preston violinmakers’ planes were made in quantity, and must have been in demand when they they were sold. During the early 20th century, in Britain, Preston violin planes established a standard of excellence amongst the instrument makers’ community. Norris violin planes were less common, although they were made from the late 19th century, right up to the early 1940s. Because of this relative scarcity, as well as the cachet of the Norris brand, Norris violin planes are currently sought after by antique tool collectors.

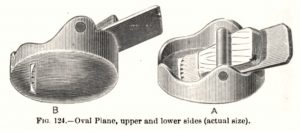

In the Preston 1909 catalogue, the drawing showed an “EP” logo on the side of the luthier plane. I have not seen this on actual Preston violin planes, which are generally marked with “PRESTON” and the logo “EP” on the end of the cutting iron. Both Preston and Norris had a number system of 1 through 5 for the range of sizes of their violin planes, but the gradation used by the two firms was opposite: for Preston, no. 5 was the largest 2 1/8″ size, and for Norris, no. 1 was the largest 2 1/8″ size.

Large 2 1/8″ Preston violin plane, c. late 19th, early 20th century. The iron is bedded on what looks to be rosewood infill.

Norris and Preston violin planes in Buck & Ryan catalogue, 1938. Norris planes came at a premium. Note: Norris’ no. 1 was the large 2 1/8″ plane, and Preston’s no. 5 was their 2 1/8″ plane.

Norris Violin plane, showing earlier 90 degree knurling, and dividing line in center. Photo from Norrisplanes.com

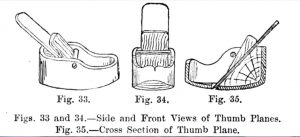

Preston and Norris violin planes look very similar, and small differences only appear with direct comparison of the two planes, which rarely happens. Also, some of these small differences can be attributed to variations in casting and machining batches.

An exception to this was the differences in knurling on the adjusting wheel. Preston had simple ridges at 90 degrees, and this was consistent throughout the many years of production of this plane.

Norris, on the other hand, went through an evolution, of at least three types. The first type had ridges at 90 degrees, with a dividing line around the center of the perimeter of the adjustment wheel(c. < 1920). This dividing line was consistent throughout Norris’ many years of production of their Violin plane.

The second Norris knurling type consisted of fine ridges at 45 degrees (c. 1920~1930). The third type of Norris knurling on their Violin planes was a coarse series of ridges at 45 degrees (c.1930-1943). This evolution roughly followed knurling patterns on other Norris planes.

Adjustment wheel on the Preston is 1″ in diameter, and the Norris adjustment wheel is 1 3/32″ The flanges for the cross pin are narrower on the Norris, and in general, the Norris has more delicate features than the Preston, has a thinner casting, and has a mouth opening that is overall smaller than the Preston. The functional mouth opening, with the iron extended, is fine in both planes, and is quite similar, however.

Preston (l.) and Norris (r.) violin planes, both 2 1/8.” View from front. Lever cap on the Norris is 1/8″ shorter than the Preston lever cap.

I examined the photos of a good many Norris Violin planes at Norrisplanes.com and also looked at a number of images of Preston Violin planes, which were made in greater quantity than the Norris planes, in order to confirm that the differences between these two planes extend to other examples as well.

Copies of Preston and Norris Violin Planes

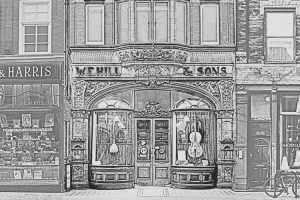

Set of W.E. Hill & Sons England Violin planes. Photos by Jim Bode

W. E. Hill, London, Violin plane, with elaborate stamp showing 1762 founding. Photo by Robert Leach, oldhandtools.co.uk, c. 2016.

W. E. Hill, London, Violin planes, side view. Planes were similar to Norris and Preston Violin Planes, so probably date from the same time period, c. 1890-1940. Photo by Robert Leach

W.E. Hill and Sons. Opulent showroom at 140 New Bond St., London, opened in 1897, and closed in 1974. W.E. Hill & Sons was famous for making bows in-house, and selling fine violins.

W.E. Hill was a prominent London Violin dealer, who traded in some of the finest instruments. Additionally, Hill had an in-house staff of fine bowmakers, and instrument repairers, which earned them a great reputation.

Set of 3 later G.E. Scarr Luthier planes, with Preston-style lever caps. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, U.K. March 2016.

Three Violin Planes made by G. E. Scarr, Hessle (Hull) Yorkshire, c. <1940-1965>. Sizes are 2 1/4, 1 3/4, and 1 3/8 inches. Inside of castings have red japanning. Photo by Jim Bode, 2016.

Hull is on the Humber estuary in East Yorkshire County. Scarr was a well known ship building family in Hessle, but I have not yet found G.E. Scarr, maker of luthier planes. While rare, there are a number of these that show up on the market from time to time.

Geoffrey E. Scarr lived at 17 Ferribly Road, Haltemprice, Yorkshire (East Riding). In 1939, Scarr was 21 and single; he worked as an Aircraft Draughtsman.

Update: Geoffrey Ewalt Scarr was born in Hessle, Hull, Yorkshire on 27 October, 1918 to Henry F. Scarr and Daisy Runnacles.. I have not found any evidence so far that Scarr was a professional luthier. In 1939, just after WWII broke out, Scarr was an aircraft draughtsman: this was a skill easily transferable to creating accurate drawings for a foundry. Geoffrey married Shirley L. Gale (1930-1997) in early 1952, and they had four children. Then in 1960, when Geoffrey Scarr traveled to the U.S., he was engaged in business with the Russell Manufacturing Co. in Middletown, Connecticut. The Russell textile firm was established in 1834, and made its fame through developing the first elastic fabrics in 1841. By the late 19th century. Russell Mfg. Co. was the largest U.S. manufacturer of suspenders, and they employed 900 workers.