Portrait of Jean Estève (1807-1892) Image from Estève et Compagnie.

The origin of Léon Pinet et Cie. of Paris, France began with Jean Estève, an expert ironworker, in 1840. Estève (1807-1892) established his company in the Marais, in Paris, where he fabricated parts for both pianos and harmoniums, specializing in making reeds for harmoniums. Harmoniums were very popular in France during the mid-19th century.

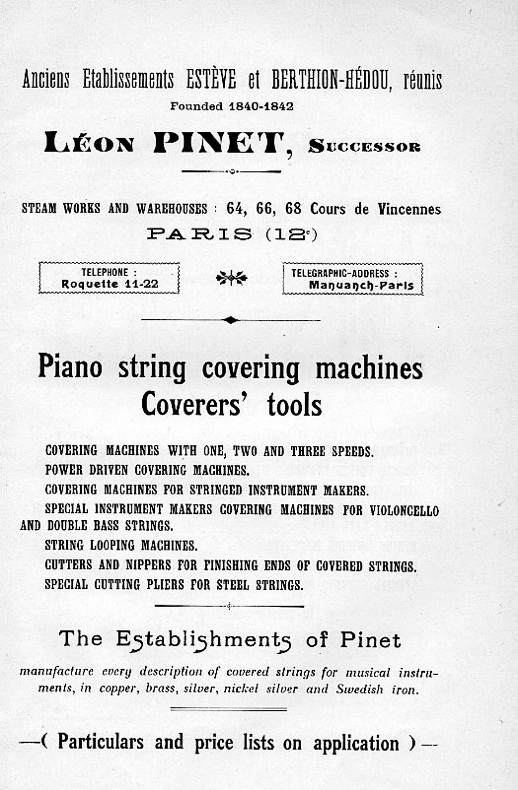

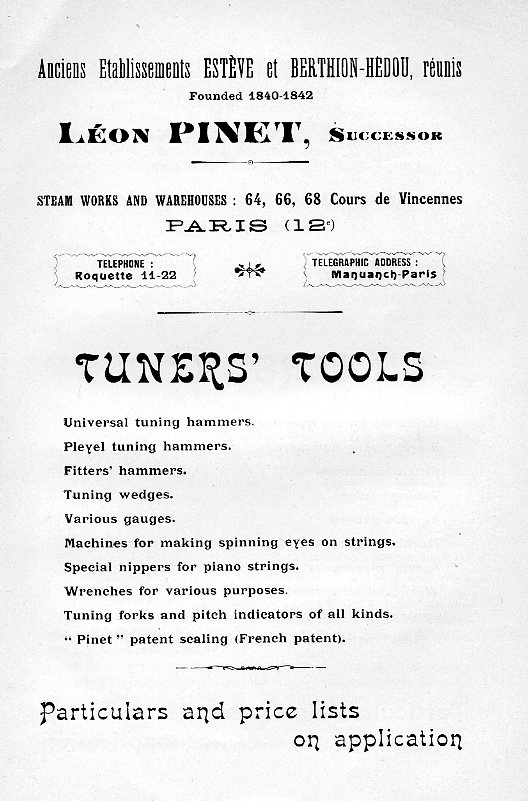

Léon Pinet assumed management of Estève in 1875, and bought the company c. 1880-1885. Pinet expanded the piano tool and supply component of the business considerably.

French Harmonium (after 1886), made by Victor Mustel (1815-1890) and his son Auguste Mustel, Parisian Harmonium makers. Photo from Metropolitan Museum, New York City (public domain).

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, a notable few composers were creating original works for the harmonium. These included Sigfrid Karg-Elert, of Germany, Cesar Frank, of Belgium, Dimitri Shostakovich, of Russia, William Bergsma, of the United States, and Antonín Dvořák, of Bohemia.

After WWI, the American Reed Organs and European Harmoniums lost popularity, but the instrument gained a new life in India, in a smaller form. My daughter owns an Indian Harmonium.

Diagram of reed, as incorporated within a French Harmonium. Image from Manuel pratique de l’accordeur de pianos et harmoniums : traitant … by E. Nugues, H.C. Pouget and Ch. Martin.

Jean Estéve’s excellent work established him as one of the best known brass reed makers for harmoniums, used by many English as well as French manufacturers, such as Mustel. In 1850, Jean Estève was searching for an apprentice, and he hired Léon Pinet. Jean Estéve introduced a new alloy for reed making in 1852. By 1872, Estéve employed 44 craftspeople. Estève merged with Berthion-Hédou (another French reed maker), and then Léon Pinet assumed management of the workshop in 1875, which was located at 14 rue Morand, Paris at that time. Jean Estéve and Léon Pinet won several awards in international exhibitions: a bronze medal in the 1878 Paris Exhibition for precision work, and a first prize in Sydney, Australia in 1880. Pinet continued to win prizes for his products in cities all around Europe as well as St. Louis in the United States, until the outbreak of The Great War in 1914 (see photograph of the Pinet Showrooms shown below).

Esteve Free Reeds, as advertised in “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner,” Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

Jean Estéve, and later Léon Pinet, supplied reeds to many of the most prominent European harmonium makers, including: Mustel, Paris; Christophe and Etienne, Paris; Balthasar-Florence, Namur, Belgium; Dumont and Lelièvre, Les Andelys, France; Richard, Étrépagny and Paris; Alexandre, Ivry-Sur-Seine and Paris; Johannes Titz, Löwenberg, Germany; H. Beaucourt, Lyon, France.

In 1880, Léon Pinet married the granddaughter of Jean Estève, and also bought the business, which became Estève et Compagnie. Léon Pinet then developed and expanded this musical instrument supply business, increasing their involvement in piano tools and supplies, and opening another branch in Belgium. A respectable time after Jean Estève passed away in 1892, the company name was changed to Léon Pinet, Paris. By 1915, Léon Pinet’s wife took over the business, which was continued unchanged.

Georges Pinet took control of the company in 1926, divested from the piano and harmonium supply business, and then concentrated on making general hardware, such as hinges and locks. This product diversification began 5 years earlier, in 1921. After several relocations in France, and an addition of another factory in Tunisia (2013), the Pinet Co. is still in business today, under the same family ownership. In 2019, there was a transfer of Pinet shares to Estève & Compagnie, in recognition of the original founder, Jean Estève. This information was sourced, in part, from a January 2021 interview with Guillaume Bataille, a 6th generation Estève descendant, who has directly controlled the Company since 2019.

A Virtual Tooling Tour of France, showing some of the places covered in this website. Image from google maps (modified).

- Villedieu-les-Poêles, a center for fine dovetailed copper glue pots.

- Léon Pinet et Cie. of Paris.

- Mirecourt, a violin family-making and bow-making community in Northeastern France.

- Jenzat, a luthier makers’ town which specializes in Hurdy-Gurdy making.

- Thiers, a knife and blade-making town, going back to the 1200s. French equivalent to Sheffield or Solingen.

- Firminy, a center for early forging, then steelmaking, where the famous Firminy piano strings were made.

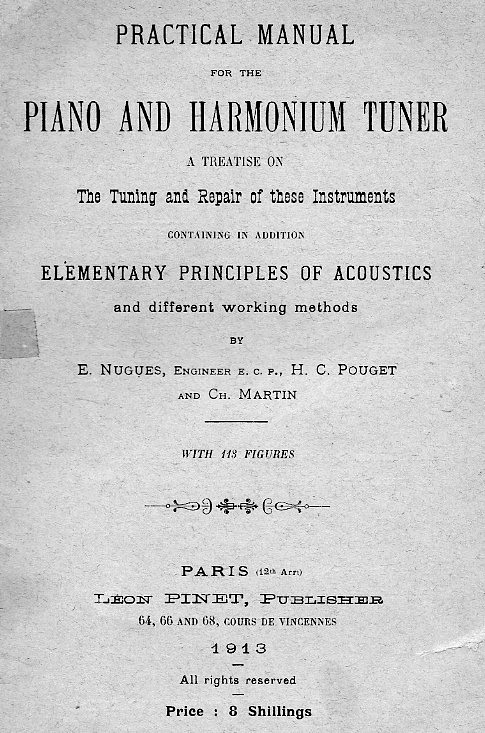

I first found the “Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner” at a used bookstore in New York in 1983. I was restoring an old harmonium at the time, and had no idea how to proceed, so I purchased this book. It had more material and information on pianos, which I found interesting, then and now. It was translated from the original French edition, and published for the British market.

The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner was originally published in French, in 1902. Pinet published this English edition in 1913.

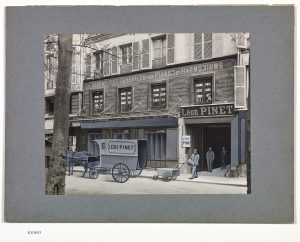

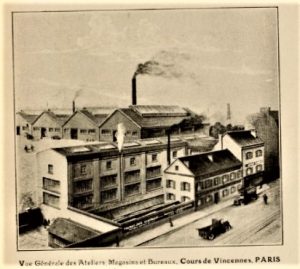

The image below is a hybrid photograph and drawing. The people, Horse and wagon, and some building details, were drawn in. Signs on the second floor tell much about the interesting piano and harmonium supply products that Pinet offered before WWI.

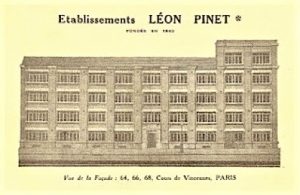

Another view of Pinet’s Factory, 64-68 Cours de Vinccennes, Paris. From c. 1914 Pinet price list, in the collection of the Music Museum of Paris.

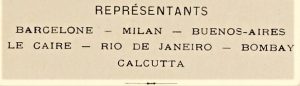

The 1914 Pinet price list showed an impressive array of goods and services for the French piano and harmonium industry that were available during the heyday of of the business. Pinet representatives were stationed in the Middle East, South America, and India.

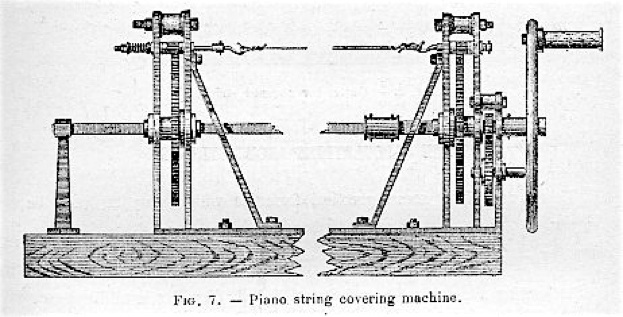

Machines were available to the industry to make bass strings of all kinds. From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner,” Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner,” by Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

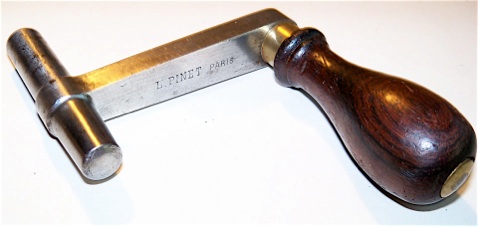

Pinet loop tool, for making the braids, or twists on the hitchpin ends of many European and historical pianos. From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner, ” Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

Individual String Winding Tool, L’Art d’accorder soi-meme Son Piano: Une method sure, simple et facile, deduite des principles exacts de acoustique et de l’harmonie, written by Claude Montal

Pinet made the heaviest constructed stringing crank that I have ever seen. For winding coils around tuning pins.

The Pinet universal tuning hammer catalog entry can be seen on the “Tuning Hammers” page. A limited number of these Pinet hammers were made with an ivory handle. Here is an example with a rosewood handle that sold on eBay in April 2014:

“Pleyel” pattern Pinet tuning hammer, in lever mode.

“Pleyel” pattern tuning hammer, composed of three [tuning hammer] heads with ball [shaped joint], mounted on a rod, and a socket handle.

Universal Tuning Hammer Model “Institute for the Blind” consisting of a steel handle lined with ebony, 1 tapped rod, two straight tubes, long and short (nos. 418 and 419), two short ball shaped hammer heads, and two long ball shaped hammer heads.

Examples of other universal tuning hammers in lever form, from top: Marque Accorda, France; Weygandt, Stuttgart, Germany; Alfred Dolge, N.Y.; unmarked, extra long, for large square pianos. Not commonly found, Universal hammers were made during the transition from the use of ‘T’ shaped hammers towards levers for tuning purposes. The Accorda and the Weygandt both contain a screwdriver inside the handle.

Pinet type tuning hammer. From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner,” Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

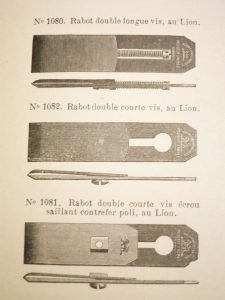

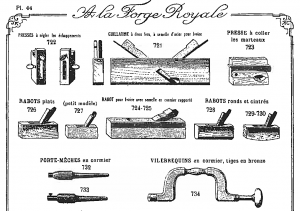

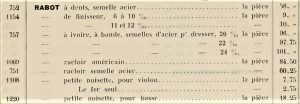

I am including some catalogue images of French Pianomakers’ Tools because the c. 1914 Pinet price list did not contain images of their products. Images of Pinet tools and supplies would have been published in a separate catalogue. Although the resolution of this 1905 Lemainque Tool Catalogue image is not great, it was old enough to still show the bow drill. Later catalogues omitted that important piano tool.

Pinet Bow Drill with bronze spool and buffalo horn [top handle], with 2 beaks [pads], 1 bit, and 1 screwdriver. From Pinet c. 1914 price list.

A distinguishing feature of French pianomakers’ bow drills as well as pianomakers’ bit braces was the extended neck, or baluster mounted handle. A worker would definitely stand up while using these tools.

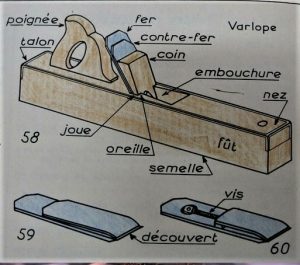

French Varlope, with terminology. Image from lairdubois.fr

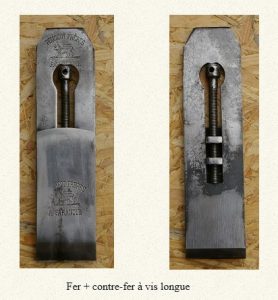

Two aspects of the French bench planes really stand out for me. The first is the continued application of the double iron (fer et contre-fer) without a slot and connecting screw. The use of double iron without screw was a design that fell out of practice in England and America in the late 18th century. Pinet offered his Varlope without screw (743), and with long screw and slot (1156).

This Thomas Wales double plane iron shows the arrangement that has been standard for bevel down planes in England and North America for the last 200 years. A machine screw with cheese head under the cutting iron, goes up through the slot and into the brass bolster of the cap iron (England), or chip breaker (U.S.A.). The wooden bed of the plane body would be mortised out to provide clearance for the cheesehead screw.

Here are some Peugeot Freres et Cie catalogue images of their cap iron with long screw and short screw. Production of the long capstan screw arrangement was primarily limited to France and Germany, with most users working in France, Austria, and Switzerland.

Fer et contre fer a vis longue. Photo from Arcoma.fr

The other unique aspect of so many French tools, was the use of Cormier wood, sometimes called “Service wood.” The Cormier tree grows almost exclusively in Southern Continental Europe. Cormier wood has very fine grain; freshly cut, it has a color towards orange, and as the cormier ages, it darkens to a warm brown tone. Cormier is a dense wood. Cormier wood was sometimes used for the jacks in 18th century French and English harpsichords, and also for harpsichord bridges.

For those who are interested in seeing these unfamiliar trees, there is a stand of about a dozen Cormier trees in the former Luther Burbank experimental farm in Sebastopol, California. These Cormier trees are about 100 years old, but the tree can easily live to 400 years. Cormier trees have a structural form that appears somewhat like extra large apple trees, and they have more abundant fruit yields than just about any other fruit tree. Unfortunately, the fruit only becomes sweet when the fruit is overripe.

It is not a good idea to plant the Cormier tree too near a house or building because the abundant fruit attracts hordes of insects and other wildlife which consume the fruit. Cormier trees do not have any invasive aspects, but their abundant fruit crops have severely restricted where the tree can be planted. Cormierwood lumber is virtually impossible to find today.

Distribution Map of the range of Sorbus Domestica (Cormier Tree). From Chorological maps for the main European woody species, by Caudullo, G., Welk, E., San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., 2017.

In France and Germany, many craft workers continue to use wooden bodied planes to this day, in contrast to England and North America, where metal planes have predominated since the late 19th century. Interestingly, the metal mitre planes and luthier planes originated in Continental Europe.

Rebate planes in the 1927 Feron et Cie Tool catalogue: 718. Standard rebate. 719. Chisel plane. 720. Bullnose plane.

Feron et Cie took over the business of Lemainque & Andre. I am including their images here because the resolution is somewhat better, but they were the same drawings over many years, which was often the case. Notably, the bow drill was omitted by 1927.

722. Clamps for adjusting escapements [of pianos].

721 Rebate plane, with two irons, with steel sole for ivory. 723. Clamp for gluing felt hammerheads.

726. Smooth planes, flat sole. 727. small model.

724-725 [Mitre] plane for ivory with inlaid cormier wood sole. 728, 729, 730. Smooth planes round [radiused] and compass.

732. Drill bit pads in cormier wood. 734. Bit Brace, in cormier wood; neck in bronze.

In France, the two main makers of pianomakers’ braces were Aux Mines de Suede and Mathieu, who also made pianomakers’ bow drills, which can be viewed on the Bow Drills page. French pianomakers’ braces were characterized by having an extra long neck, a stock made of cormier wood, and socket accommodating tapered bit pads. In this case the braces are in cormier wood, but the pads are a mixture of oak and ash. While the braces may look like they are ‘tipping their hats’ to each other, that’s just a distortion of the camera lens; the cormier wood handle on the left and the buffalo horn handle on the right are perfectly level. These two French braces would have been what Léon Pinet had available to buy in during his years of doing business.

When the French tool company “Aux Mines de Suede” (From the Mines of Sweden) opened for business in the 1840s, the loss of the Napoleonic Wars and the battle of Waterloo (1815) were still within living memory. Given that, and the general rivalry between the British and the French over the centuries, it made sense to advertise Swedish steel over Sheffield steel, even though Sheffield was closer to Paris than Sweden.

By the 1860s, an appreciable amount of French cast steel began to be produced, part of which was used for the burgeoning French edge tool industry.

752. Plane with toothing iron, and steel sole. 1154. Finishing plane.

757. Plane for dressing ivory strips [keytop blanks], with steel soles. 1069. American style scraper.

751. Scraper with steel sole. 1108. Small violin plane. The iron alone. 1220. Small plane for contrabass.

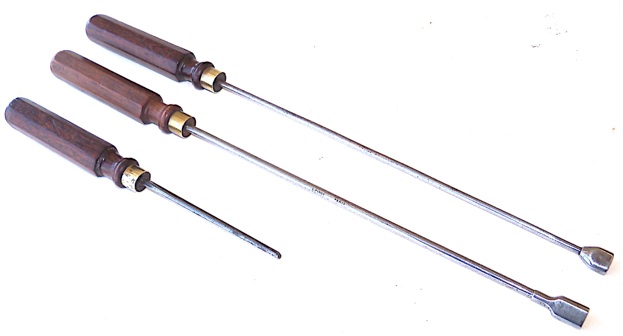

Two Pinet let-off tools; small u gouge.

Pinet regulating tools were not always marked, but they often had turned octagonal handles of the type shown above. The octagonal part of the handles was not always symmetrical; in these cases, the facets might have been made freehand, without a machine or jig, probably cut with a plane while the handle was held in a vise. The wood used on these handles could be rosewood, walnut, oak, or a stained light wood, probably beech. Here are two long and thin let off tools, and another specialized tool, a converted small U gouge, with blade rounded and smoothed, probably used to ease damper wires in the guide rails on grand pianos:

Inscription on let off tool shown above, middle.

Pinet tools, with typical octagonal handles. From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner,” by Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

“A square bit or small broach for fitting screws or enlarging holes.” Reamer.

The design of these old French tools was different than what was made in the U.S. or Japan, but was somewhat closer to some German examples. The tool in the center has bending slots in the same arrangement as the general action wire bender made in the U.S. for many years, but the shape is different.

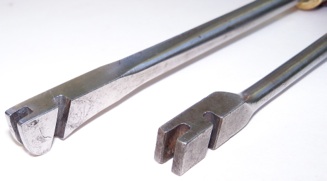

Closer look at wire bending tool, above.

Comparison of the French wire benders and a standard H. S./ Erlandsen type. The slot at the front of the French tool is at 90 degrees, and the American type is around 70 degrees, parallel to the slot on the side. The U. S. version on the right is still sold by Schaff Piano Supply in Chicago.

Key spacer (top), and an upright damper spoon bender. The large key spacer hardware looks close to the example in the picture called the “Specimen of the tuner’s kit,” shown further down on this page.

Inscription on oak handle: T. L. R. Fasse—that’s the best that I can make out.

Additional Pinet action tools, including offset screwdriver for rocker capstans.

- 1046 Damper wire bending tool.

- 1045 Keydip regulating block, in rosewood.

- 1049 Tool for keyboard leads.

- 1001 Key spacing regulating tool.

- 1047 Pair of adjusting tools for the mechanics.

- 1114 Tool to restore the horsehair of the bows.

Downloadable versions of Pinet regulating tools:

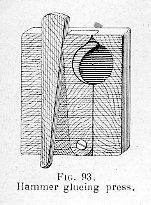

For regluing hammers that have become separated from their moulding. Another hammer clamp can be seen on the Miscellaneous page:

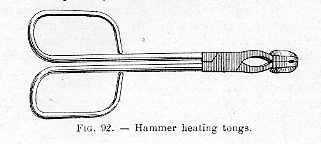

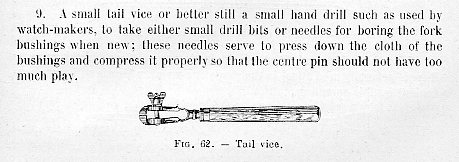

From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner.”

From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner.”

From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner.”

Pinet Tuner’s Kit, contents in French. From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner.”

Pinet’s range of tuning tools. From “The Practical Manual for the Piano and Harmonium Tuner,” by Nugues, Pouget, and Martin.

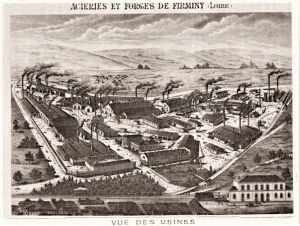

Pinet was the exclusive seller of Firminy piano strings, bars and cast plates. The town of Firminy in the Loire department was one of the largest centers for iron and steel production in France during the late 19th, early 20th centuries. A Firminy music wire gauge can be found on the String Gauges page.

Firminy Steel Works and Forges. View of factories. The smoke would not be seen as a good thing today.

Throughout the Western World, during the industrial revolution, factory owners would exaggerate the size and scope of their facilities in their published images. While Firminy was a major steel making town, the French steel industry in general was decentralized, spread out amongst many medium and small sized factories across France. The French steel industry lagged behind that of Germany, Britain, or the United States, in the late 19th, early 20th centuries.