MOON MITRE PLANES

Thomas Moon (1761-1830), and later, son John Thomas Moon (1791-1829) made planes and other tools from around 1795 to at least 1829. After John Thomas’ death, his wife Ann Moon, née Aldam (1794-1857) owned the retail operation located on 4 Little Queen St. from 1831 to 1848. Along with John Moseley & Son, and Holzapffel, the Moon business was one of the few tool warehouses in London that presented their tools in a true retail setting.

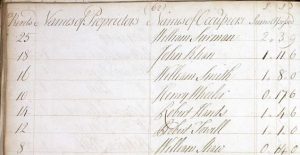

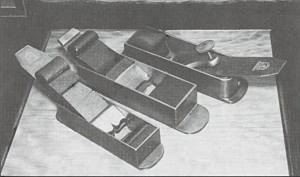

Moon 10″ 4 Little Queen St, Lincoln’s Inn Fields; Archer 45 Goodge St. 9″ (Spiers); Buck 9″ 245 Tottenham Court Road (Towell); Moon 8″ 145 Sat. Martin’s Lane; Moon 8″ 4 Little Queen St. Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London; Buck 245 Tottenham Court Road (Holland). Mitre planes from the collection of James Claussen (with the exception of Moon 145 Saint Martin’s Lane).

Three Moon mitre planes, interspersed amongst some other interesting mitre planes, within the collection of James Claussen.

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

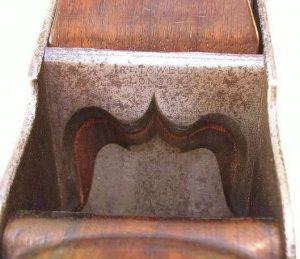

This Moon mitre plane is visually similar to a Towell mitre until one lines the Moon up next to some Towells to see that they do not match. It is not known who made the mitre planes from 1829 to 1848, even whether or not they were made in-house by employees, family members, or bought in. Moon mitres also featured a Cupid’s bow on the bridge, as did many English makers of wrought iron mitre planes in the early 19th century.

Number 878 in Antique Woodworking Tools, by David R. Russell. 10 1/8″ long, with a 2″ iron by James Cam, set at 23 degrees. Dovetailed body, and two piece sole joined by tongue and groove. Typical metal plane construction of the period. Looks like a former owner used a screwdriver on the wedge when adjusting the iron.

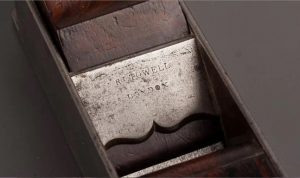

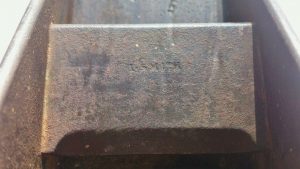

MOON 4 Little Queen St. Lincolns Inn Fields LONDON. Front infill removed, showing 4 internal lugs that are pinned through the sole from underneath. This arrangement has left the mouth fairly fine after almost 200 years.

This plane may appear to have a moveable front sole piece, for adjusting the throat, but that is not the case. In front of the fine mouth, is a separate front sole piece that is pinned to the body through four internal lugs on the sides.

Moon mitre plane, 9 1/4″ long, also in cast iron, with similar front plate. Photo from oldhandtools.co.uk

Moon cast iron mitre plane, 9 1/4″ long. also with fitted front sole plate. Replaced front infill. Photo from MJD Auctions, Oct., 2021.

Thomas Moon, Cabinetmaker

Baptism of Martha Wilks, daughter of Colin and Mary Wilks, Cannon St. Road, at Tower Hamlets, St. George in the East, 18 December, 1757.

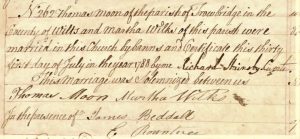

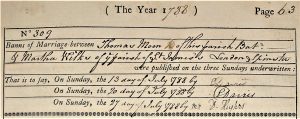

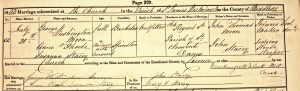

Thomas Moon, who was born circa 1761 in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, married Martha Wilks (born 1757, died 18 October, 1841) of St. James, Picadilly, London, on 31 July, 1788.

Thomas & Elizabeth Moon, baptized 18 September, 1763, in Trowbridge. Wiltshire. Parents: William and Martha Moon, parish of St. James.

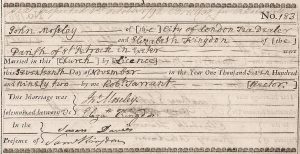

Thomas Moon of Trowbridge, Wiltshire married Martha Wilks of St. James, Picadilly, London, on 31 July, 1788.

Banns of Marriage for Thomas Moon and Martha Wilks. Published 13, 20, 27 July, 1788, St. James, Trowbridge, Wiltshire.

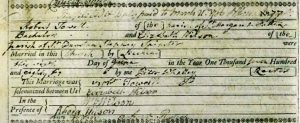

John Thomas Moon, born 1 February 1791; Baptised 11 February 1791, at St. Martin in the Fields Church.

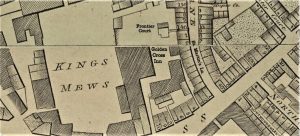

Plying the trade of a cabinetmaker, Thomas Moon established his and Martha’s home on Frontier Court, which was off of Saint Martin’s Lane, just north of the Golden Cross Hotel at Charing Cross. Thomas and Martha had at least 7 children, who were all baptised at Saint Martin in the Fields Church, across Saint Martin’s Lane, on the east side of the Lane:

- George Moon, born 20 April, 1788, baptised 30 May 1788. Burial 2 May 1802 St Martin in the Fields.

- John Thomas Moon, born 1 February 1791, baptised 11 February 1791. Died 12 September, 1829.

- Ann Gilson Moon, born 31 July, 1792, baptised 16 September, 1792. Died during or before 1800.

- Rachel Umphleby Moon, born 29 June 1794, baptised 15 August, 1794. Died in childhood.

- William Wilks Moon, born 16 April, 1797, baptised 1 June, 1797. Burial 2 June 1814 St. Martin-Fields.

- Georgiana Moon, born 10 May 1801, baptised 29 June, 1801. Died 9 Dec. 1877, 62 Camden Sq. London.

- Frederick Alexander Moon, born 16 August 1803, baptised 25 September, 1803. Burial 30 Dec. 1803 St. Martin in the Fields.

Frontier Court, Saint Martin’s Lane

On 18 August, 1790 Thomas Moon took out a Sun Insurance policy: “Thomas Moon Carpenter, His wife [Martha Wilks] a Seamstress; Frontier Court, Saint Martin’s Lane”

When Thomas Moon was just starting out, he did not have many material assets. In 1790, he insured his stock of timber (lumber) for £50; his tools and misc. for £10; Martha Wilks Moon’s inventory of apparel for £40. Total £100. What the Sun Insurance policies did not reveal were intangible assets, such as money in the bank.

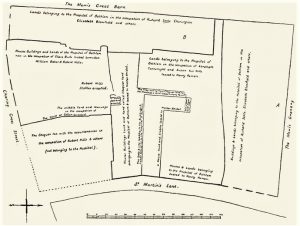

Land claimed by Bethem Hospital at Charing Cross, circa 1649. From “Survey of London: Volume 20, St Martin-in-The-Fields, Pt III: Trafalgar Square and Neighbourhood,” Edited by G H Gater and F R Hiorns (British History Online).

Frontier Court was located in the section marked “A” in this map of the land claimed by Bethem Hospital in the Charing Cross location.

In 1792, at St. Martin’s Lane (Frontier Court), Thomas Moon took on an apprentice named William Gaff, for training in woodworking.

Sarah Sims Kidnapped Two Year Old Ann Moon

This incident, and others like it, illustrated just how dangerous it was to live in London in the 18th and 19th centuries.

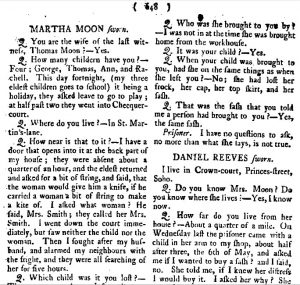

On 20 May, 1795, Thomas and Martha Moon arrived in a London Court room, to serve as witnesses in a crime committed involving the Moon family as victims.

Old Bailey Online: SARAH SIMS was indicted for feloniously stealing, on the 6th of May , a linen frock, value 1s. a cotton skirt, value 1s. a linen cap, value 1s. 6d. and a silk sash, value 6d. the goods of Thomas Moon . But the really serious crime was that Thomas and Martha Moon’s 2 year, 9 month old daughter Ann, was kidnapped by Sarah Sims for part of a day.

Sarah Sim’s kidnapping was driven by desperate poverty, which was rampant in London of the 18th century.

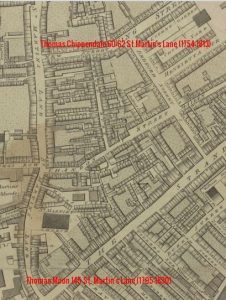

Moon’s Tool Warehouse and Chippendale’s Saint Martin’s Lane Workshop

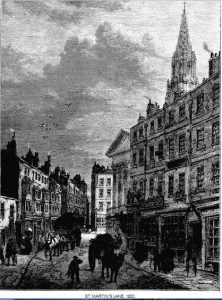

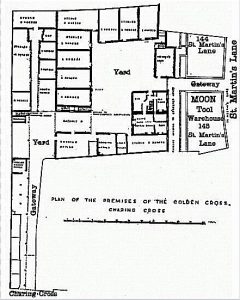

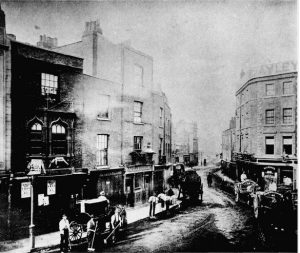

By 1795 Thomas Moon set up his original shop on St. Martin’s Lane at no. 145. The Moon Tool Warehouse remained at 145 St. Martin’s Lane until the area was cleared in 1830, for the building of Trafalgar Square. Earlier, Thomas Chippendale & Son also had a shop on this street, no 60-62 from 1754 until their bankruptcy in 1813. Chippendale wrote the influential book, “The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director,” which was a collection of furniture designs in Gothic, Chinese, and Rococo styles as well as domestic pieces. It was published in 1754. Chances that Thomas Moon and Thomas Chippendale Jr. never met would be close to none.

Thomas Chippendale’s Workshop at 61-62 Saint Martin’s Lane, was a large operation. Members of Chippendale’s large staff would have been good customers for the Moon Tool Warehouse.

Thomas Moon, “Carpenter’s Tool-Warehouse,” 145 Saint.Martin’s Lane, 1799 Holden’s London Trade Directory.

1800 Coach Accident at Golden Cross Inn

Storefronts on St. Martin’s Lane in 1830, including Thomas Moon’s retail store and entrance to the Golden Cross Inn. Drawing done by George Scharf.

In the “Pickwick Papers,” by Charles Dickens, in chapter II Mr. Jingle gave an account of a coach accident at the entrance to the Golden Cross Inn at Charing Cross. Here is Charles Dickens’ fictional account of the accident which was purported to have occurred, circa 1827:

‘Heads, heads–take care of your heads!’ cried the loquacious stranger, as they came out under the low archway, which in those days formed the entrance to the coachyard. ‘Terrible place–dangerous work–other day–five children–mother–tall lady, eating sandwiches–forgot the arch–crash–knock–children look round–mother’s head off–sandwich in her hand–no mouth to put it in–head of a family off–shocking, shocking! Looking at Whitehall, sir?–fine place–little window–somebody else’s head off there, eh, sir? He didn’t keep a sharp look-out enough either–eh, Sir, eh?’

The following quote came from the “Survey of London: Volume 20, St Martin-in-The-Fields, Pt III: Trafalgar Square and Neighbourhood,” Edited by G H Gater and F R Hiorns (British History Online). Gater and Hiorns described the low entrance to the Golden Cross Inn between 144 and 145 Saint Martin’s Lane:

[The Golden Cross Inn] had an entrance to St. Martin’s Lane between Nos. 144 and 145. It was from the Golden Cross that the immortal Mr. Pickwick started on his journey to Rochester and it is of interest to not that Mr. Jingle’s story of the lady who lost her head had some foundation in fact, for on 11 April, 1800, as the Chatham and Rochester coach emerged from the gateway of the Golden Cross “a young woman, sitting on the top. threw her head back, to prevent her striking against the beam, but there being so much luggage on the roof of the coach as to hinder her laying herself sufficiently back. it caught her face, and tore the flesh…in a dreadful manner” –an accident which afterwards proved fatal.

Here is the account in the “Annual Register” of the coach accident that actually occurred almost 30 years earlier, on 11 April, 1800.

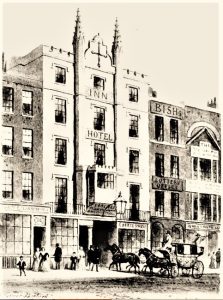

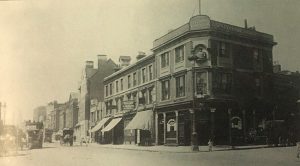

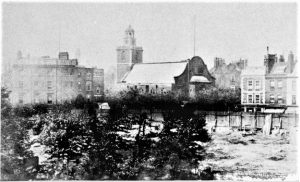

Golden Cross Inn, with entrance to St. Martin’s Lane and Moon’s Tool Warehouse. Drawing (modified) from British History Online.

The Golden Cross Inn had been established there since Elizabethan times. This hotel catered in large part to travelers who took stagecoaches throughout southern England. There were two coach entrances to the hotel. The entrance at Charing Cross led to a small courtyard, and the entrance in Saint Martin’s Lane, between nos. 144 and 145 led to to a much larger, primary courtyard. Problem was, the St. Martin’s Lane entrance was very low, as seen in the George Scharf drawing from circa 1829.

The Charing Cross entrance had much more head clearance, as seen in the circa 1820 drawing by T. Hosmer Shepherd.

This drawing of St. Martin’s Lane was located a block south of St. Martin’s Church, looking north. The Moon Tool Warehouse would have been off to the left of the image.

Sun Insurance Policies

The Moon family insured their homes as well as their business with the Sun Insurance Company of London, which was established in 1710. Sun Insurance Company was the oldest documented insurance company in the world. These insurance documents revealed much about those who took out policies, including life circumstances and aspects of their business and trade.

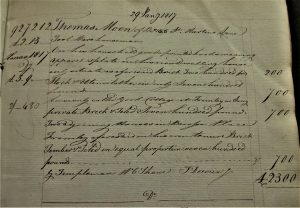

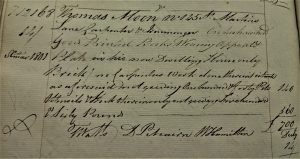

2 January, 1801, Sun Insurance Policy: Thomas Moon, Carpenter and Ironmonger, 145 St. Martin’s Lane.

Thomas Moon was insured for the following: general goods, wearing apparel, and “plate” for £140; tool inventory for the warehouse business (“utensils”) for £560. Thomas Moon was really building his capitol in the 1790s. Total £700.

“No Carpenter’s work [to be] done therein situate as aforesaid.” So insuring a carpenter meant that his property would not be covered if he did carpentry work in them? It is interesting to see how the insurance industry has not changed in over 200 years.

Thomas Moon continued to acquire more property as time wore on. In 1817, he insured his household goods at £200; his tool inventory for the St. Martin’s Ln. warehouse at £700; York Cottage in Frimley for £700; Two additional houses at Barossa Place, Frimley for £700. Total £2,300.

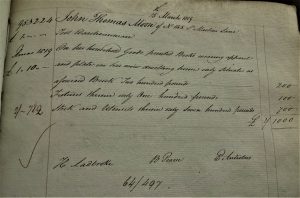

15 March, 1819 marked the time when Thomas Moon fully retired to Frimley, and John Thomas Moon fully took over the Moon family tool business. Not shown here is the likely inter generational transfer of capitol from father to son, that would have occurred at this time as well.

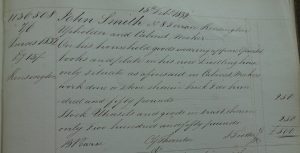

In this Sun Insurance contract, John Thomas Moon insured his family’s household items for £200; home fixtures for £100; tool warehouse inventory for £700. Total: £1,000.

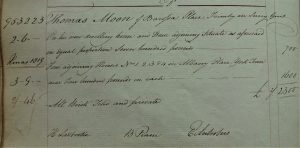

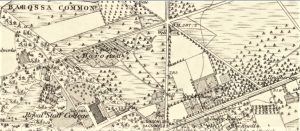

Thomas Moon Barossa Place, Frimley

In 1810, with an eye for his future retirement, Thomas Moon bought property at Barossa Place, Frimley (now Camberley), in Surrey County. Coming of age in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, Thomas Moon was likely a country gentleman at heart as compared to a London City dweller. Or Thomas could have grown weary of witnessing the poverty, accidents, and crimes so ingrained within the London environment at the turn of the 19th century.

Thomas Moon’s land was located just north of London Road, and directly east of King’s Ride. At the time he purchased his land in Surrey, Thomas Moon was still working and running his Tool Warehouse at 145 Saint Martin’s Lane, in London. Thomas continued to work running the Moon Tool business until 15 April, 1819, when his son John Thomas took over, and Thomas retired to Frimley.

Thomas Moon insured his home for £700; four houses, 1, 2, 3, and 4 Albany Place, York Town, for £400 each, or £1,600. Total £2,300.

Thomas Moon spent a good portion of his wealth on his properties.

Land taxation records remain extant for the Frimley property, called “York Cottage” by Thomas Moon, from 1813 through 1830, the year of Thomas’ death.

“[Thomas Moon’s land] was a distinct triangle in which he built his house which he named York House.” –Mary Ann Bennett, genealogist.

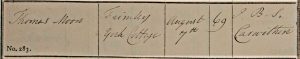

Thomas Moon, in the 1830 Land Tax records for Frimley, Surrey. His home, presumably York House, and a second parcel, Barossa Place.

The following land record came from the repository of the Surrey History Centre, in Woking, ref. no. 6876/53, and the document was dated 12 June, 1810:

Attested copy of appointment and release by John Tekell of Frimley, and others, to Thomas Moon of Mark [St. Martin’s] Lane, London, of a triangular plot of land at Frimley, Ash, near the Royal Military College, measuring 19a 3r 16p, abutting the Bagshot-Blackwater turnpike to the south, and the Kings Rides on the other two sides. This land, originally waste of the manor of Frimley, had been part of the whole enclosed by a private act of 1801.

Of the 7 known children of John and Martha Moon, only John Thomas and Georgiana were included in Thomas Moon’s will, written 20 March, 1824, and amended with a codicil on 21 February, 1826. Sadly, the only Moon children of this generation who survived beyond childhood were John Thomas and Georgiana. While relatively generous arrangements in Thomas’ will were made for his wife Martha Wilks Moon, and Georgiana Moon, Thomas only left £20 for his son John Thomas. The reason for this paltry sum may have been because the transfer of wealth from father to son had already occurred in 1819, when the Moon Tool business changed hands. Just 3 months after taking over the business at 145 Saint Martin’s Lane, John Thomas got married.

Thomas Moon passed away in Frimley on 4 August, 1830, and he was buried on 7 August 1830.

After the death of Thomas Moon, his widow, Martha Moon, continued to live at York House in Frimley, along with her daughter Georgiana. Georgiana Moon married Joseph Symonds, a grocer, on 3 November, 1837, in the Parish Church of Frimley, Surrey. Shortly after getting married, Georgiana, Joseph, and Martha moved back to London, setting up housekeeping at Queen’s Row, Pimlico. On 6 August, 1838, George James Symonds, son of Georgiana and Joseph, was baptised at St. George, Hanover Square.

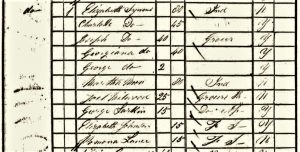

Martha Moon, in the 1841 U.K. census, living on Queen’s Row, with her daughter Georgiana Symonds nee Moon.

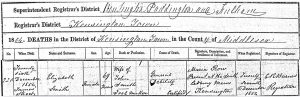

Martha Moon passed away at her residence at Queen’s Row, Pimlico, London, on 18 October, 1841, at the age of 84. Martha died with a legacy of £300, with £200 to be left for her daughter Georgiana, and £100 to be divided 5 ways, between her grandchildren, the surviving children of the late John Thomas Moon (d. 1829): Henry, Sarah, George Washington, Martha, and Charles.

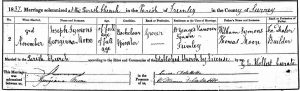

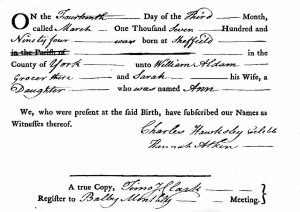

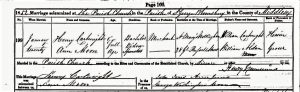

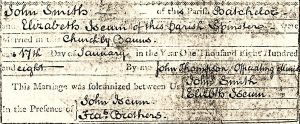

John Thomas Moon married Ann Aldam of Sheffield on 13 July, 1819

In 1805, at the age of 14, John Thomas Moon began his apprenticeship with Hawksworth & Peniston, Joiners and Tool Manufacturers of Sheffield, Yorkshire. This training would have lasted 5 to 7 years, or until around 1812. During those years spent in Sheffield, John Thomas would have had ample opportunity to meet and court Ann Aldam, of Upperthorpe. John Thomas waited to marry Ann until after he had taken over the business on 15 April, 1819. The courtship between Ann and John Thomas was apparently longer than was typical, likely as long as 8 to 10 years, while the average time of courtship in England was around 21 months in early 19th century England.

John Thomas Moon, 28, traveled to Sheffield to marry Ann Aldam (born 14 March 1794) of Upperthorpe, Yorkshire, on 13 July 1819 (license procured 24 June). John Thomas brought Ann back to London with him.

Until 1821, the Moon business was listed in the London Directories under Thomas Moon. From 1822 through 1828, John T. Moon, or just John Moon was listed at 145 St. Martin’s Lane.

Thomas Moon, in the 1820 Kent London Directory. An artificer was an archaic term for a skilled craftsperson.

William and Sarah Aldam, of Sheffield, Yorkshire, were Quakers.

Children of John Thomas Moon and Ann Aldam Moon

All of the births of John Thomas’ and Ann Aldam Moon’s children were recorded in in the Quaker’s Westminster Meeting House. Ann Aldam was raised as a Quaker, but John Thomas’ and Ann’s family belonged to the Anglican Church. The recorders in the Quaker records were quite diligent about writing “Not a member” in all the Moon family’s Quaker documents. Here are the birth and death dates of the children of John Thomas Moon and Ann Aldam:

10 June, 1820, Birth of Henry Moon at [78] Regent St., St John the Evangelist. Quaker Birth Registry. Died after 1881, as Henry Moon was staying with his brother, George W., at 164 Coach and Horses Yard, Westminster, during the 1881 U.K. census.

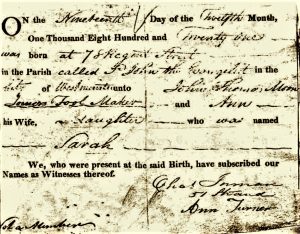

19 December, 1821, Birth of Sarah Moon at 78 Regent St., St John the Evangelist. Quaker Birth Registry. Died 22 July, 1865, Bedford.

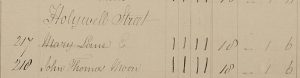

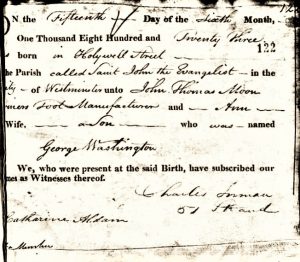

15 June, 1823, Birth of George Washington Moon, Holywell St., Saint John the Evangelist. Quaker Birth Registry. Died 11 March, 1909, Brighton.

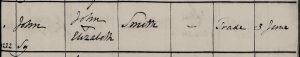

Sarah Moon, born 19 December, 1821, at 78 Regent St., St. John the Evangelist. Quaker Birth Registry.

1823 15 June Birth of George Washington Moon, Holywell St., Saint John the Evangelist. Quaker Birth Registry.

29 March, 1825, Birth of Martha Moon, Holywell St. Quaker Birth Registry. Died 16 March 1907 Leicester.

15 March, 1827 15 March, Birth of Charles Moon. Holywell St. Quaker Birth Registry. Died 14 July, 1909 Croyden, Surrey.

10 February, 1829, Birth of John Thomas Moon Jr., Holywell St. Quaker Birth Registry. Died before 1837, as John Thomas Jr. was not included in Martha Moon’s 1837 will.

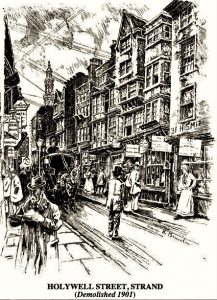

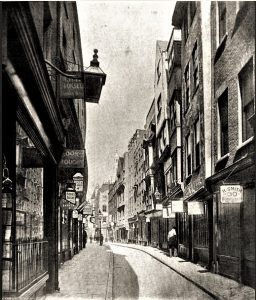

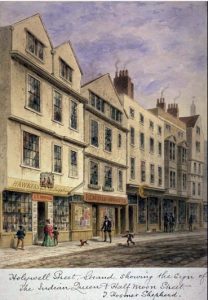

The Moon family in the Notorious Holywell Street

John Thomas and Ann Aldam Moon lived in Holywell St. from 1823 to 1829, which was a short walk from 145 Saint Martin’s Lane. Many radical political books were published in Holywell street in the late 18th, early 19th centuries. By 1815, the local authorities began cracking down on what they saw as seditious activities. At that point, the publishing industry at Holywell resorted to selling pornographic books. As residents of Holywell St., the Moon family would have experienced firsthand, the transition from political manifestos to pornographic material. Legitimate publishers, however, were also plying their trade on Holywell Street. By 1835, there were around 50 publishers of pornography on this short one block long street between St. Clements and St. Mary’s at Strand. The street was run down and narrow: many of the buildings were from the Elizabethan era, and were designed with cantilevered upper floors, which leaned over the small street. Despite the fact that the area was described as being worn down and in disrepair, Holywell Street was shown to be populated by well off residents in Charles Booth’s 1890s Poverty Map of London.

This drawing of Holywell St. captured the closed-in surroundings and the furtive nature of the booksellers’ patrons.

Razing Holywell Street did not rid London of pornography.

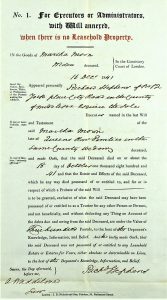

Will of John Thomas Moon

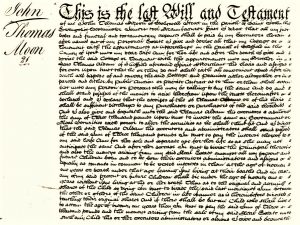

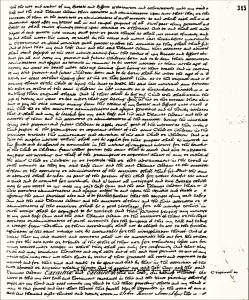

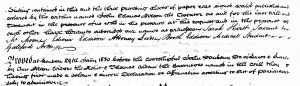

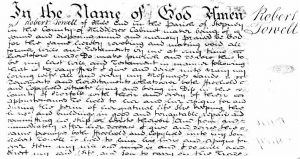

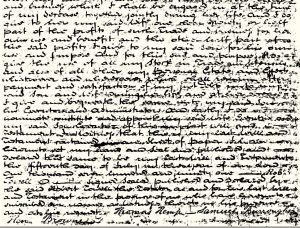

The 4 December, 1827 will of John Thomas Moon, was proven on 29 January 1830. Thomas Aldam and Ann Aldam Moon were present on the 29th. At just 36 years old in 1827, John Thomas Moon may have been suffering from health problems which prompted him to put his affairs in order.

John Thomas Moon left his cottage in Upperthorpe, Sheffield, Yorkshire, to his wife Ann, for the rest of her days. John Thomas also left his savings of £3,000 (about $360,000 today) to his brother in law, Spirit Merchant, Thomas Aldam. Thomas Aldam was to use the interest generated by this capitol to provide for living expenses for Ann, for the remainder of her life. Additionally, the interest on £3,000 was to be applied to help provide for Thomas and Ann’s children until they reached the age of twenty.

Thomas Aldam died in Sheffield on 27 April, 1858, with a nest egg of almost £5,000. How much of that money (if any) might have come from John Thomas Moon?

It was unclear where John Thomas had made his £3,000. It could have come from his father Thomas, when the business changed hands, or it may have come in the form of a dowry from the Aldam family of Sheffield. Or John Thomas could have made a lot of money himself, because the early 19th century was a lucrative time to be selling high end craftworkers’ tools in a retail setting. Possibly John Thomas pieced together his savings from all of these sources, and others too.

This photo of Upperthorpe, taken ~70 years after John Thomas left his Upperthorpe cottage to Ann Aldam Moon, shows the industrialization of this neighborhood over the intervening years.

In 1829, John Thomas’ name was crossed out in the Westminster Rate books, which usually meant gone or dead.

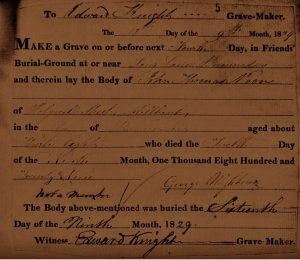

John Thomas Moon died on 12 September, 1829, and was buried on the 16th. “Not a member” of the Society of Friends.

This burial was in a Quaker cemetery near Long Lane, Bermondsey St. in Southwark.

After the Death of John Thomas Moon

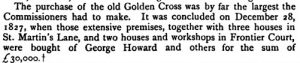

Sale of Golden Cross, Frontier Court, and Houses on St. Martin’s Lane to the Crown. From “The Gentleman’s Magazine,” Volume 149, c. 1831.

Ann Moon was forced to vacate her Tool Warehouse in 1830, because the neighborhood needed to be razed in order to clear space to build Trafalgar Square. When Ann Moon moved her tool warehouse to 4 Little Queen Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, she listed the business under John Thomas’ name in the 1831 Trade Directory.

As Ann Moon carried John Thomas’ name over to the new warehouse at 4 Little Queen Street, it was also seemingly apparent that she carried her late husband’s name over to her residence on Holywell St. John Thomas Moon[e] continued to appear on Holywell Street documents from before 1833 to after 1863. After further scrutiny, however, this was not Ann fronting the name of John Thomas Moon (1791-1829), or the name of John Thomas Moon Jr., (1829-<1837). It was yet another John Thomas Moon (or Moone, 1799-1865), at 8 and 9 Holywell Street, who was a herald and coach painter.

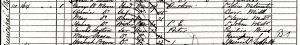

John Thomas Moone, and son John James Moone, Herald painters, at Nos. 8-9 Holywell St., in the 1851 U.K.census.

Since Holywell Street was only 1 block long, these two Moon families were almost certainly related. And there was a good chance that John Thomas and Ann Aldam Moon had lived at 8 Holywell St. from 1823 to 1829, and when Ann left Holywell St., before 1833, she left her residence to John Thomas Moone.

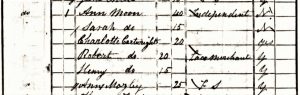

Ann Moon of “Independent Means,” living in East Leake, Nottinghamshire, along with her daughter Sarah Moon, in the 1841 U.K. census.

Sometime after the death of her first husband in 1829, and before the 1841 U.K. census, Ann Moon moved to East Leake, Nottingham, and befriended Henry Cartwright (1805-1855). Henry Cartwright owned a Lace Manufactory at Hound’s Gate, Nottingham in 1844.

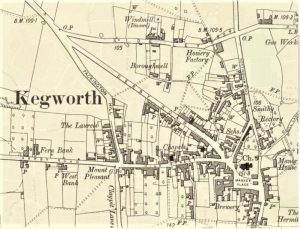

Moving from London to Nottinghamshire was a major lifestyle change for Ann and Sarah Moon. East Leake is a town of 7,000 people today.

Thank you to Catherine Morton Lloyd, a Moon descendant, who was able to steer me correctly to Ann Aldam Moon’s relocation in Nottinghamshire, England. I had been looking for years for information on Ann’s later personal life, which has not been generally known previously. Additionally Catherine Morton Lloyd rediscovered the 1824-1831 will of Thomas Moon, and the 1837-1841 will of Martha Moon nee Wilks, while she and I were corresponding, and which she generously shared with me.

It was notable that only one of Ann’s children, Sarah Moon (b. 1821) was living with her in 1841. Given that Ann Moon would have been receiving income from both her business as well as the interest income from the £3,000 that John Thomas had left her (and possible rental income from her inherited house in Upperthorpe, Sheffield), Ann Aldam Moon would not have been hard pressed financially to pay someone to watch over her children. Also, Ann did not appear to spend a lengthy period of time (if any) at her inherited cottage at Upperthorpe, Sheffield. Since Ann Aldam was born in Upperthorpe, there was a distinct possibility, if not likelihood, that this cottage in Upperthorpe was originally part of a dowry payment from the Aldam family to John Thomas Moon at the time of their marriage in 1819.

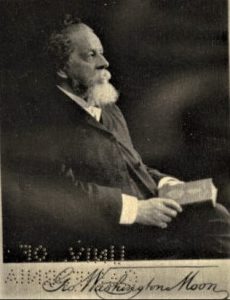

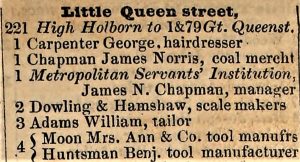

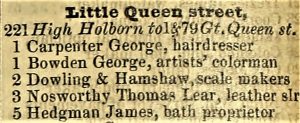

Financial independence also enabled Ann to employ Benjamin Huntsman to run the Moon Tool Warehouse at 4 Little Queen Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Holborn, London. Benjamin Huntsman, obviously named after the pioneering inventor of crucible steel in 1743, lived at 4 Little Queen St., and was recorded as living there with his family in the 1841 U.K. census. None of the Moon family members were recorded as living at or adjacent to 4 Little Queen St., in the 1841 U.K.census.

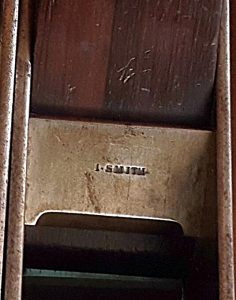

Moon mitre plane, marked on front infill: 4 Little Queen St. Photo from D.Stanley Auctions, Lot 582, September, 2016.

Benjamin continued to work for Ann until at least 1848, presumably making wooden planes and various other tools for Ann Aldam Moon, and her Moon Tool Warehouse.

Mary Huntsman, “Dealer in Tools,” and Benjamin Huntsman, “assistant,” at 8 King St., Holborn, in the 1851 U.K. census.

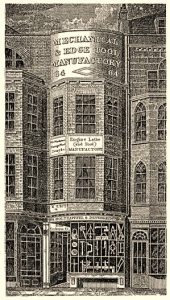

Mary Huntsman, an older sibling of Benjamin’s, was also living at 4 Little Queen Street during the 1840s. Mary observed the Moon Tool business with a keen eye, and used that experience as a pathway towards running her own tool business. Some wooden planes with the Huntsman mark read “HUNTSMAN LATE MOON 8 KING ST. HOLBORN.” This mark would have been made after Ann Moon closed her business in 1848, as Benjamin’s sister Mary was listed at 8 King Street from 1850 until 1863.

At first, Mary Hunstman employed Benjamin to continue making tools, and this can be observed in their 1851 U.K. census entry. Later on, in the 1861 U.K. census, Mary’s nephew John Smith Lester was making some of the tools for her business. But by the time of the 1871 U.K. census, Mary Huntsman declared her profession as “Tool Maker,” with no assistance from other family members. This could have meant that after all of her years watching other family members make tools, she decided to make tools herself. Or most likely, it could have indicated that Mary Huntsman bought in all of her tools by 1871. From 1867 to 1876, Mary Huntsman’s tool business was listed at 16 Southampton Row.

Mary Huntsman’s tool business, while long-lived, was a small operation, and it was run out of her residence; in no way should it be considered a continuation of, or successor to, the Moon Tool warehouse. Mary Huntsman shared her addresses at 8 King St. and 16 Southampton Row with many other tenants, so the necessary space for conducting a tool trade would have been limited.

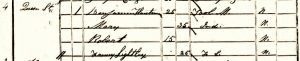

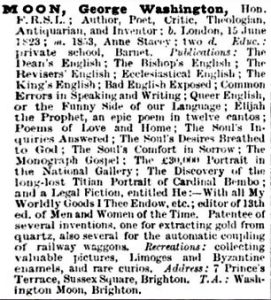

Other contributions to Moon’s line of tool merchandise at 4 Little Queen St. could have come from their son Henry (born 10 June, 1820) after 1835. In the 1851 U.K. census, Henry Moon declared his profession as “Engineer,” and the training for that was possibly derived from his experiences around the Moon Tool Warehouse. George Washington Moon established himself as a notable author, poet, and critic, with a number of books to his credit. Somewhat of a polymath, George Washington Moon was also an inventor, with patents for several inventions, including one for extracting gold from quartz, and several for the automatic coupling of railroad cars. Geo. Washington’s mechanical abilities may well have been honed at the Moon Tool Warehouse. Charles Moon went on to work as a lace merchant, following in the footsteps of his stepfather, Henry Cartwright.

At the time of the 1881 census, Henry Moon, “C.E. [Civil Engineer]” was living with his brother, author and inventor, George Washington Moon, at 164 Coach and Horses Yard, Westminster, London.

Expensive mitre planes may have been bought in and rebadged from Edward Cox, who was a close neighbor, at Plough Court, Fetter Lane in 1830, 26 Little Queen St. from <1833–1841>, and 15 Great Queen St.from <1843–1854.

This type of front infill was not unique to Moon or Cox, but it is a piece of information to be considered, along with the proximity of these two makers.

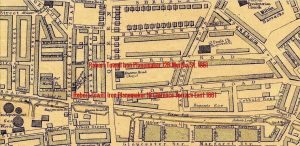

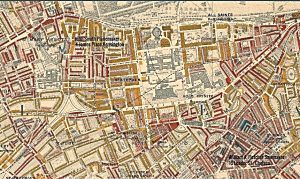

Detail of Richard Horwood’s 1792-99 Map of London, showing Moon’s Tool Warehouse (1830-1848) and planemaker Edward Cox’s workshops (1833-1854).

For the 1831 through 1848 listings at 4 Little Queen Street, John Moon’s name was omitted from the London Directory listings and sometimes Ann Moon’s name was added.

In the London Street Directory for 1847, Ann Moon and Benjamin Huntsman were listed together at 4 Little Queen Street, Holborn.

1848 was the last year for listing the Moon Tool Warehouse in the London City Directories

In 1849, 4 Little Queen Street was omitted, implying that the premises were unoccupied. This was also the case in 1850

By 1851, 4 Little Queen Street, Holborn was again listed, occupied by Henry Alexander Donaldson & Sons, Upholsterers.

After the Closure of the Moon Tool Warehouse

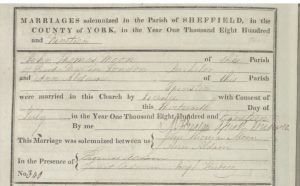

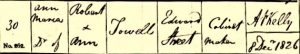

George Washington Moon married Anne Stacey, at Saint James Church, Westminster, 20 July, 1853. Father John Thomas Moon: “Joiners’ Tool Maker, deceased.”

The paper trail for Henry, Sarah, George W., Martha, and Charles Moon picked up after 1850. John Thomas Jr. (born 1829) may well have died during childhood. Here is the marriage document for George Washington Moon in 1853, which included his father, John Thomas.

Martha Moon Married Thomas Chapman Browne Esq., on 19 December, 1854. From Nottinghamshire Guardian, 21 Dec., 1854.

Ann Moon, “Tool Maker’s Widow; Accountant,” with Henry and Martha Moon, and Henry Cartwright, 86 Side Ley St., Kegworth, Leicestershire, in the 1851 U.K. census.

Kegworth is a small town with around 3,600 residents, located 12 miles southwest of the city of Nottingham.

Ann Moon was staying at 28 Great Russell Street in 1852, before she married Henry Cartwright. Son George Washington Moon was a witness.

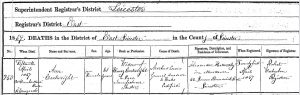

Sadly, Henry Cartwright died three years after marrying Ann Moon. Ann was widowed a second time.

Less than two years after the death of Henry Cartwright, Ann herself passed away.

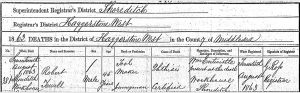

Morbus cordis means ‘no more than heart disease,’ or death by natural causes. General anasarca 10 weeks means acute edema from head to toe for 10 weeks. Ann Aldam Moon Cartwright would have been 63, not 61. Henry Cartwright was a “Lace Manufacturer (Master).” Henry Cartwright owned a Lace Manufactory at Hound’s Gate, Nottingham in 1844. By 1847 Henry moved his factory to High Pavement, Nottingham.

More Images of Moon Mitre Planes

Cast 7 3/4 inch Moon 4 Little Queen St., Lincoln’s Inn Fields, view of sole, with fine mouth (for a cast bevel up plane).

Moon mitre plane, 8 inches long, dovetailed, with ebony infill and Greaves iron. Stamped “145 Saint Martin’s Lane,” which would date it to pre-1830, or during Thomas’ and John Thomas Moon’s lifetimes.

Moon mitre plane, 145 Saint Martin’s Lane, view of heel, with Greaves iron, rear flange, and cheesehead screw.

The wooden mitre plane, made of beech, with a boxwood throat closer, was a less expensive alternative to the iron mitre plane.

Wedge is a replacement in this plane.

Robert Towell, Iron Planemaker

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

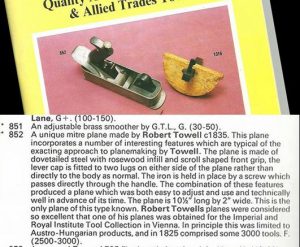

Towell worked in the early 1800s, from c 1810, until as late as 1863. Robert Towell is generally recognized as the first full time maker of infill planes, first mitre planes, and then later some rebate planes, and a handful of panel planes.

Moseley operated a posh tool shop at 17-18 New Street, in a retail district of Covent Garden during the 1830s.

John Moseley was probably not a “Tea Dealer” in London, but rather a Tool Dealer. One of Elizabeth Kingdon’s brothers may have been a business partner with John Moseley, possibly Zachary Kingdon, who died 16 May, 1795. Witness Samuel Kingdon Sr., (1746-1797) was an ironfounder in Exeter.

Moseley advertised an establishment date of 1730, but evidence pointed to the 1790s as a more realistic time frame. This 1794 entry for Kingdon & Moseley was one of the earliest.

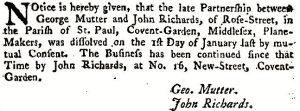

Dissolution of partnership between George Mutter and John Richards. London Gazette, 10 September, 1793.

Perhaps John Richards was a silent partner of Kingdon & Moseley, at 16 New Street, Covent Garden.

By 1820, as evidenced in this trade directory, the Moseley firm was branching out and supplying a more broad range of tools and supplies.

Max Ott, whose name is stamped on the Moseley/Towell mitre plane shown above, was a 20th century cabinet maker and collector who was born in Switzerland but worked in England. Ott stamped most of his tools in the old style. Other planes that came through the hands of Max Ott, and included in my pages on George Buck are a Holland mitre plane, which was pictured, an I. Tremain mitre plane, and a Norris custom mitre plane. The Norris custom mitre was purchased by Ott at auction in 1989, and written about by Maurice Fraser in Fine Woodworking Magazine.

A few salient characteristics of Towell mitre planes:

- Consistently long rosewood front infill, with the lip of moulding directly over the mouth.

- Cupid’s bow cut more deeply into bridge–often at 45 degrees–than contemporaries (exceptions exist).

- Use of I. & H. Sorby irons, with no nib, and stamped on the side of the bevel, also Ward & Payne.

- At the heel, there are two bends (corners), rather than one large horseshoe bend, as with Gabriel mitres.

- Sidewalls 3/16″ thick compared to Gabriel mitres at around 5/32″.

- Two dovetails in front of the mouth, three dovetails behind the mouth, on each side.

- Bridge attached to cheeks with two pins, on each side.

- Front and rear sole pieces dovetailed together at the mouth.

- Front flange has ~3/8″ long straight section protruding from the front plate before making the curve at the extreme toe.

- Rear infill variations: some examples with rosewood; some have matching rosewood lamination over a stained hardwood bed. Other rear infills are beech or mahogany.

Towell Variations:

Infill beds on Towell mitre planes: Buck 245 Tot. Ct. Rd., oak; Moseley, beech; Towell, beech; Towell, solid rosewood ( P. Kingdon stamped on plane bed, perhaps related to Kingdon & Moseley); Joseph Buck, beech capped with rosewood; Towell, late rounded body, solid rosewood.

Robert Towell was famous for filing his Cupid’s Bow decoration rather deeply into the bridge, with the file cut at a pretty low angle, but not all the time. Throughout his working life, Towell established clear structural and stylistic patterns, which he then broke on occasion.

Sometimes Robert Towell would skip making the Cupid’s Bow altogether, a feature which epitomized his planes more than any other. These planes were still of the highest quality.

Another example is the tongue and groove joint at the mouth, which Towell was known for. Sometimes Robert Towell would bypass this step completely, and put dovetails on either side of the mouth instead. Here are two examples of this shortcut:

Robert Towell alternative construction: dovetails on either side of mouth, rather than tongue and groove joint on the two sole plates. This is the same plane as the one in the photo w/o Cupid’s Bow. Photo by Jim Bode Tools.

Some Towell Family History

Because little has been known about Robert Towell (Born March 28, 1790–died November 17, 1871) generally, I have included the following information on his life. Robert Towell’s vital documentation has been known to a handful of genealogists for a number of years, but within the antique tool arena, an absence of information on Towell was noted in British Planemakers from 1700, by Goodman and Rees, Third edition, 1993, as well as in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell, in 2010. As recently as as 2016, a major collector who has done research, wrote an email to me regarding a lack of documentation for Robert Towell. Information was sourced from the websites, familysearch.org, findmypast.com, and ancestry.com, as well as various other sources.

Robert Towell’s father and grandfather were cabinetmakers. Grandfather Robert Towell was born in Diss, Norfolk in 1732 and baptized on 2 January, 1733. Robert married Mary Butcher (1734-1806) on 9 November 1758, in Suffolk, England. The young Robert Towell and his family moved to Stepney, Mile End, Old Town, London, sometime after the baptism of their son John on 10 April, 1762 in Diss, and before 1768, when they were taxed in London.

Robert Towell Sr. and Jr., cabinetmakers, Crown Row (Opposite Harry’s Head Pub), Mile End, Old Town, London. Richard Horwood’s c. 1792 map of London.

Towell’s location was provided in a Sun Insurance document from 1774. Mile End Road was surrounded by fields in the 1790s.

Little has appeared to change on Mile End Road in these images captured over a century later:

Robert Towell I was buried 7 September, 1791, at St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney Tower Hamlets, Middlesex, England.

In his last will and testament, Robert Towell I passed on his house, land, and buildings that he owned in Diss, Norfolk to his wife, Mary Butcher. To his son Robert Towell II, he passed on his cabinetmaking business in London, with the stipulation that one half of the profits went to his widow, who went on to outlive him by 15 years. In the 18th century, the Towell family was solidly within the middle class.

Baptism of Robert Towell “0,” “sonn of Thomas and Martha Towell,” 12 October, 1698. Parish of “Disse, Norfolk.” Interred 25 March, 1778 Diss, Norfolk.

For the relevant purposes of covering the life of Robert Towell III and his pioneering planemaking work, I have designated Robert Towell (1732-1791) cabinetmaker of Diss, Norfolk and London as “Robert I.” But this Robert Towell was not actually the first one. The Towell family was established in Diss long before written records were introduced in the late 17th century.

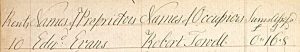

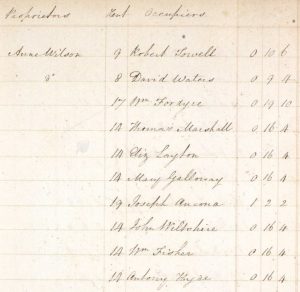

Robert Towell’s parents were Robert Towell II (1759-1825) and Elizabeth Wilson (1757-1837). In the Wilson family, traditionally, the men were mariners. Robert Towell II was a tenant of Ann Wilson, Elizabeth Wilson’s older sister b. 1756, and her husband Edward Evans (m.1773). As early as 1781, Edward Evans was landlord to the Towell family, then around 1792, Edward died, and his widow Ann Wilson took over as landlady, until at least 1799. On the face of it, Robert Towell I and II had a more comfortable life than Robert Towell III and IV; Robert III and IV paid a heavy price for becoming one of the first English metal planemakers.

Robert Towell married Elizabeth Wilson at Saint Margaret Pattens Church, 6 June, 1786. Ann Wilson, witness, among others.

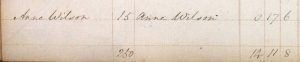

Anne Wilson (b. 1756), was a landlady to 10 tenants, including Robert Towell, and her sister Elizabeth. Stepney, Land Tax, Mile End Old Town, Tower Hamlets, London, 1799.

Robert Towell II took on an apprentice in cabinetmaking, George Daysh, on 28 September, 1790. Robert III was 6 months old.

Robert Towell II took on another apprentice in cabinetmaking, William Giles, on 29 August, 1792. Robert III was 2 years old.

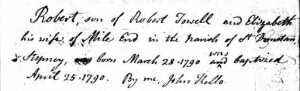

Robert Towell was born 28 March, 1790, and Christened 25 April, 1790 at Cambridge Road, Independent Meeting, Bethnal Green, London, England.

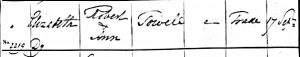

Robert Towell had an older brother, also named Robert, who did not survive. Robert, 21 days old, was baptized on 24 June 1787, at Saint Stephen’s, Stepney. In some cases, this has resulted in giving Robert Towell, the planemaker, an earlier, incorrect birthdate. Robert and Elizabeth repeated this pattern of renaming a child who died, with Elizabeth, born 23 July, 1794 and died 12 November, 1794. Their next daughter, also Elizabeth Towell, was born 8 March 1796 and died 24 November, 1870, in Saint Leonard’s Workhouse, Kingsland Road, Shoreditch.

In accordance with traditional practice, Robert III would have started his apprenticeship in cabinetmaking with his father in late 1804, and this would have continued until as late as 1811. By this time, 21 year old Robert Towell was likely aware of the innovative iron mitre planes sold by Christopher Gabriel. Interestingly, when Robert Towell had the opportunity to make his own mitre planes, he did not directly copy the work of Gabriel; he established his own style instead.

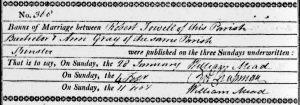

Robert Towell married Ann Gray (b. Kenton, Devon 1790-1859 London) on 28 January, 1816. Robert and Ann had a number of children, including the following: Robert Jr., b 29 November, 1816-d 17 August, 1863 Shoreditch, London; Elizabeth b 17 September, 1819-11 Oct., 1819; Ann Frances, b 11 Sept 1820, d. July, 1824; Martha, b 01 October, 1822, d. March, 1823; Joseph, b 18 January, 1824, d. 18 March, 1864; Anna Maria b 8 Dec 1826- 31 May,1848; Eliza Caroline b 12 Nov 1830-19 March, 1869. Robert Towell and Ann Gray had better luck with their children surviving until adulthood than Thomas Moon Sr.’s family, but still, it must have been rough going.

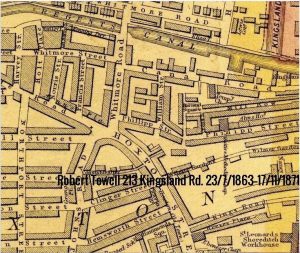

Robert Towell and Ann lived in Marylebone, and their childrens’ Christenings took place at St. Mary’s, St. Marylebone Road until 21 June 1824, when Joseph was baptized there. The next recorded Towell baptism took place for Eliza Caroline, at Saint Leonard’s Church in Shoreditch on 19 December, 1830 (Eliza Caroline was born 12 November, 1830). Ann Maria was born 8 December, 1826, but she did not receive a baptism until 30 June, 1837, at Saint John the Baptist Church, Shoreditch, on 30 June 1837. During the period around 1826, the Towell family was likely preoccupied with moving from Saint Marylebone to Shoreditch.

Baptism records for the Towell family, when available, gave some indication of Robert Towell’s profession in his early adulthood, but not conclusive evidence. Since Robert Towell was not listed in any of the London City Directories, the Baptism records are the only documentation of Robert Towell’s early years in his profession, besides his actual planes.

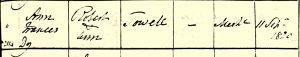

Baptism of Ann Frances Towell, 11 September, 1820. Robert Towell III was a “merchant,” probably selling iron planes.

Baptism of Martha Towell, 15 Oct, 1822. Robert Towell listed as “merchant,” probably selling iron planes (and cabinet work).

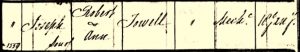

Baptism of Joseph Towell, 20 June, 1824. Robert Towell recorded as a “merchant.” Joseph (d. 1864) went on to become a chair maker and carver.

Baptism of Eliza Caroline, 19 December, 1830. Robert Towell reported his profession as “cabinetmaker” residing on Edward St. in Shoreditch.

Baptism of Anna Maria Towell, 30 June, 1837. Robert Towell recorded as “cabinetmaker” on Edward St. in Shoreditch.

Robert Towell and his family lived on Edward St. in Shoreditch for many years. These early listings as “merchant” and “cabinetmaker” are are not at all exclusive of the likelihood that Robert Towell was making iron mitre and rebate planes as a sideline in the 1820s and 1830s, and possibly as early as 1810.

Robert Towell Jr., born 29 November, 1816, baptized 22 December. at St. Marylebone. Robert Sr. was working a “trade.”

Robert Towell Jr. joined his father in the business of making planes. Robert Jr. did not marry.

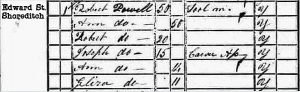

Robert Towell, 51, lived on Edward St. in Shoreditch in 1841, and he stated his trade as “tool maker.” Even though the occupation for Robert Jr. was left blank, he was of the age to have been assisting his father in business. I am not aware of any extant generalized woodworking tools made by the Towell family. For the remainder of his long life, Robert Towell remained in Shoreditch.

The census enumerator made a mistake on the spelling of Towell (not “Powell”). It was one of the reasons that Towell was so hard to find for years.

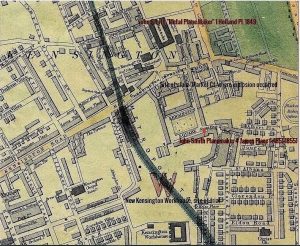

1 Edward St. Whitmore Rd. Home and workshop of Robert Towell, 1826-1848>. 1850 J. Cross Map of London.

Before 1850, Edward St. was an obscure half block long segment of Phillip Street. There was another more well known Edward St. in Shoreditch, just north of the intersection of Old Street and Shoreditch High Street. This Edward St. Whitmore Road was documented in the death certificate of Ann Maria Towell in 1848.

All of Robert Towell’s future addresses can be found on this map: 12B Martha St. 1851; 14 Princes St. 1859; 10 Clarence Terrace East 1861 (Dunstan Rd. in 1850) ; Shoreditch Workhouse 1863-1871.

Ann Maria Towell’s death certificate. Robert Towell, “cabinetmaker,” was living at 1 Edward St., Whitmore Road.

When Robert and Ann Towell’s daughter Ann Maria passed away on 31 May, 1848 at the age of 21, the Towell family was still living on Edward Street.

Residing on 1 Edward Street Whitmore Rd. in 1848, the Towell family at least had some stability as far as a place to live and work was concerned; they had been there since moving to Shoreditch in 1826.

A census enumerator made another mistake in the 1851 census. It should have read “Iron Plane Maker,” not Iron “Plate maker”. Enumerators were often under time constraints, and not always carefully hired. It is important not to repeat the mistakes of an enumerator by looking for patterns when in doubt.

It was not outside the realm of possibility that Towell gave the enumerator the “Iron Plate Maker” description because iron “platemaker” was more commonly understood than iron “planemaker.” This was less likely than the enumerator having made a recording error, however. Towell’s work created a finished product (iron planes), consisting of 3 iron plates and two steel plates.

Iron plate worker ; iron plater; cuts iron plates on table of power shears; bends, in bending machine or with hammer on block shape; rivets and fits up iron plates generally in connection with constructional iron work; cf. plater. From A Dictionary of Occupational Terms Based on the Classification of Occupations used in the Census of Population, 1921. Compiled by the Ministry of Labour and published by HMSO, 1927.

Shoreditch was an area where Robert Towell would have had an excellent customer base, with many highly skilled craftspeople needing the fine planes that he produced. Here is a description of Shoreditch during the period of Robert Towell’s productive years, circa 1810 to 1863:

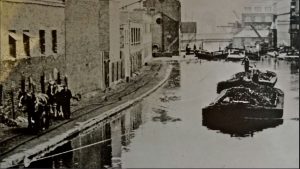

In Shoreditch artisans operated from small workshops where they lived. Tailors, ironworkers, leather workers such as saddlers and cordwainers (shoe and boot makers) were all common. Printing and furniture makers were another two predominant industries in this area, particularly in the later period. The furniture industry boomed in the south Hackney area when the Regents Canal was completed in 1820, as this eased the transport of heavy goods and materials. The furniture trade provided work for many small specialist trades such as french polishing and veneering, likewise with printing there was work for bookbinders and stationers.

By Victorian times, although the industrial revolution had resulted in most industry moving from areas around the City walls to places where land was cheaper and goods could be produced on a large scale, some craftsmen had escaped the threat of mass production. These were people working in the finishing trades and with high value artifacts. Being close to fashionable markets, Shoreditch was ideally placed and traditionally the area had a pool of semi-skilled labour. The furniture trade’s centre was Shoreditch and it flourished partly because of the Regents Canal, built in 1820, which was utilized for transporting the heavy hardwoods needed. Piano makers and showrooms abounded too. By 1901 there were over five thousand piano, cabinet and other furniture makers in Hackney and they had spread out from Shoreditch as far as Homerton.

From http://www.bonsonhistory.co.uk/html/hoxton___shoreditch.html

Sadly, Ann Gray Towell was admitted to the Shoreditch Workhouse where she spent the last six years of her life. It was unclear if the primary reason for her admission was poverty in the Towell household, or because of her condition of being “past work,” which could have been physical debility, or it might have implied the possibility of dementia.

Death certificate of Ann Towell, died 30 January, 1859. “Wife of Robert Towell, Planemaker (Journeyman).” Robert Jr. (1816-1863) present at death.

If Ann was suffering from dementia, or physical disablity, the need for someone to watch and take care of her would have seriously cut into Robert Sr. (III) and Jr.’s (IV) capacity to run their planemaking business.

At the time of the 1861 UK census, Robert Towell, 71, widower, was living at 10 Clarence Terrace East in Shoreditch. Robert Towell still reported his occupation as “Iron Plane Maker,” and that he was working with assistance of his son Robert Jr., born 1816.

From Edward Weller’s 1868 map of London, detail of Haggerston. Robert Towell was located at 12B Martha St. in 1851, and at 10 Clarence Terrace East in 1861.

Note the Regents canal, which was essential for the local piano and furniture making industry and their ancillary trades in the 19th century.

The Regent’s Canal was especially important from 1820, its year of completion, to the 1840s, after which the railroad began to predominate. Even so, the canal was used commercially into the 1960s.

Horse pulling a barge along the towing path on the Regent’s Canal. Somewhat overlooked today, Regent’s Canal is still used for recreation and boating.

Regent’s Canal, between Haggerston bridge, and Queen’s Road bridge. Photo by Richard Croft, geograph.org.uk

This is the block that included Clarence Terrace, Robert Towell’s final address before admission to Saint Leonard’s Shoreditch Workhouse. Clarence Terrace has since been renamed to Denne Terrace. The photograph was taken on the north side of Regent’s Canal, looking east, towards Queen’s Road bridge. Therefore, Clarence Terrace (now Denne) would be off to the left of the image. Large apartment buildings presently on Denne Terrace appear to date from the 20th century.

In August 1863, Robert Jr. died, and Robert Sr., a widower since 1859, went into the St. Leonard’s Workhouse at 213 Kingsland Road. Robert Sr. was admitted to the Workhouse on 23 July, 1863, while Robert Jr. was sick and presumably incapacitated. Plisithis was an early term for tuberculosis.

By the 1871 UK census, Robert Towell, 81, widower, was listed as a “cabinet maker,” and presumably an infirm “inmate” at St. Leonard’s workhouse in Shoreditch, London. Robert was most likely destitute in old age.

St. Leonard’s Shoreditch Workhouse, 213 Kingsland Rd. ; Robert Towell, admitted July 23, 1863, the same year as the death of his son Robert Jr.; discharged (death) November 17, 1871

Robert Towell’s last surviving child, Eliza Caroline, died on 19 March, 1869 in Port Arthur Tasmania at the young age of 38. Seven years later, Eliza Carolines’s family left Australia, and returned to London. For Robert III, it surely would have been difficult to outlive all of his children; living to 81 was truly an advanced age for the time.

Towell, Planemaking, and the 18th Century:

It has been suggested by several antique tool dealers that Robert Towell planes were made as early as the 18th century. Certainly, that would not be realistic with Robert’s birthdate in 1790; obviously that conclusion would have to be reached without looking at his birth records, which are now accessible. In another case, the postulation was made that since Robert Towell I (1732-1791), and Robert Towell II (1759-1825) were both cabinetmakers, it was possible that Robert’s father and grandfather not only passed down the cabinetmaking trade, but also the planemaking trade to Robert Towell III (1790-1871). There was no paper trail for Robert Towell I or II as a planemaker, or toolmaker. Robert Towell I left a will dated 15 July, 1791. There was no mention of toolmaking, or planemaking in his will.

If Robert’s father and grandfather made planes, they most likely would have been wooden, because the English metal mitre planes were only made since 1780 or so. But there are no extant 18th century wooden Towell planes, or 19th century, for that matter. And the surviving 18th century metal mitre planes, by Christopher Gabriel, John Sym, and John Green are fairly well documented. Gabriel and Sym have also left an extensive paper trail, with ample documentation around their respective planemaking professions.

Eighteenth century English metal mitre planes were a radical and expensive new innovation, rather than an old tradition, handed down from generation to generation. Previous to 1800, only Gabriel made enough mitre planes to establish a pattern with sufficient descriptive attributes. Gabriel’s planes did not have a Cupid’s Bow; the Cupid’s Bow was not added to the bridges of English mitre planes, in any appreciable quantity before the turn of the 19th century. The sidewalls of Gabriel mitre planes made a single large bend at the heel compared to two rounded corners on Towell mitres, and the thickness of Towell sidewalls were 3/16″ thick compared to Gabriel mitres at around 5/32″. The increased sidewall thickness, the double bend at the heel, and the proliferation of the Cupid’s Bow adornment were all generally (but not universally) shared 19th century features, not just Towell’s exclusively.

Irons in Towell mitre planes: 3 I.& H. Sorby (bevel side); 2 Ward & Payne (bevel side); 1 Robert Sorby (opposite side). Note how the cutters take up nearly the full width of the interior of the plane (especially at the mouth), with modest room for side to side adjustment.

Another clue in dating Towell mitre planes is in the stamps on the irons. During the 19th century, when bevel up mitre planes were the most popular, edgetool makers would stamp their dedicated mitre plane blades on the bevel side, and these were almost certainly original plane irons. There would have been a few exceptions, however. This stands in contrast to the early Gabriel mitre planes with the stamp most often opposite the bevel side.

The I. & H. Sorby stamp with the crown shown here was introduced no earlier than the 1820s. Ward & Payne marks–officially registered 1843 in Parliament– were not around before circa 1837-1843. And Robert Sorby’s kangaroo mark was registered in 1850.

I. & H. Sorby early mark, after John Sorby’s sons John Jr. and Henry joined him in business, after 1814. David Ward, early mark (before “& Co.”), circa 1805-1830.

When a tool is corroded or pitted, this does not necessarily mean that it is from the 18th century; it is possible to observe a very clean Christopher Gabriel (1746-1809) mitre plane, and it’s conjointly possible to find an Arthur Price (1897-1967) infill plane rusted to hell.

Robert Towell’s Innovations

While on the subject of Towell, here is a photo of a Towell smooth plane. It was sold in the UK through thesaleroom.com some time ago. Panel planes and rebate planes are known to be made by Towell, but this smoother was a revelation.

Another Towell smooth plane (even earlier) was observed by Mark Rees, who wrote about it in the TATHS newsletter no. 65 (Summer, 1999) and illustrated in TATHS newsletter no. 66. This Towell smoother had all the features of a classic wooden coffin smooth plane, but with some substitutions in metal: a steel sole, with dovetailed wrought iron sides. The toe and heel had rosewood infills that were left open. The inner cheeks had lugs for retaining the wedge. Many details were retained, such as chamfers at the corners, and the ‘turn out’ at the corners of the mouth. Rees thought it must have been an expensive plane to produce.

A similar, but not identical Towell smoother shown below is 7 9/17″ long, and 2 5/16″ wide. The iron was bedded at 60 degrees, cabinet pitch of the the period. The body is dovetailed, wrapped around the toe, and joined at the heel, similar to some of Towell’s later mitre planes. The sole extends beyond the body at both the toe and the heel, and was joined at either side of the mouth with a tongue and groove joint.

And here is a Joseph Buck, 124 Newgate St. smoother, with some similarities and differences as compared with the Towell smoother shown above. The J. Buck smoother does not have front and rear sole flanges, has differently shaped infills, and the sole was joined at the mouth with a simple butt joint.

This fourth example of a Towell Smooth plane has been cleaned, but appears quite similar to the other examples shown above.

Robert Towell made a small number of iron panel planes, which were among the first (if not the first) panel planes ever made.

Towell panel plane (unmarked), Bob Funnell collection. Photo from D.Stanley Auctions, September, 2014.

This Towell panel plane was pictured in Mark Rees’ article on Robert Towell, in TATHS newsletter no. 65, summer, 1999. Plane was 13 1/4″ long, 2 3/4″ wide, and had an I & H Sorby parallel iron and an Ibbotson & Co. cap iron (replacements).

Towell panel planes shown here are all transitional, showing both mitre plane and bench plane characteristics. These panel planes have a two part sole, dovetailed at the mouth, the sides are a single iron plate, bent around the heel, and the toe is a separate plate. All mitre plane features.

Towell panel plane marked and sold by John Moseley. John Moseley & Son tapered iron/cap, 12 1/2″ long, 2 3/4″ wide.

Unlike his mitre or rebate planes, Robert Towell never arrived at a standard design for his panel planes. There are at least three panel plane versions with different side profiles–that third version can be seen in Russell’s Antique Woodworking Tools, no. 1360. The cheeks of no. 1360 consisted of a straight line at the top, with no deviation, and had a front infill that was an overstuffed block, rather than a tote. It therefore appeared more like a mitre plane, and may have been earlier than the examples shown here. Towell also changed the bridges on his panel planes, with the type shown above, his cupid’s bow, and a simple arch. There are likely more variations.

A unique feature of at least several Towell panel planes was the use of two bed angles under the iron. Like a mitre plane, the bed angle at the sole was 20 degrees. –Then the bed angle was changed to the more typical 48 degrees found in later bevel down metal planes. In the Moseley plane shown directly above, there is a thick steel plate, or frog covering the lower 1 1/2 inches of the 48 degree part of the bed. The Towell panel plane owned by R.C. Funnell and written about by Mark Rees in TATHS Newsletter #65 also had this metal frog. Not all Towell panel planes have this frog, but at least one other Towell panel plane has a two part wooden bed, with the lower wooden part and sole at 20 degrees, and the majority upper part of the bed at around 45 degrees.

Some of the earliest Spiers smoothers and panel planes also included a steel plate at the lower part of the bed, as noted by Nigel Lampert in Through Much Tribulation: Stewart Spiers and the Planemakers of Ayr. (pp. 33-34). Spiers did not use a stepped bed, however–Spiers’ beds were around 47 degrees all the way through.

Here is another Towell Panel plane, dovetailed, low front plate, with sides wrapped around the heel.

Another Towell Panel plane rebadged by Moseley:

This Buck Panel plane is a bit of a mystery. It has a bridge that is very similar to those found on some Spiers mitre planes and bench planes. Most of these Spiers bridges were in gunmetal, but some were made in iron. The sides were dovetailed, but the toe and heel were left open, as in later Panel planes by Spiers. Yet the profile from the sides is very much in the pattern of Towell’s Panel planes.

Towell Mitre Planes With Handles

One of the complaints about using mitre planes was difficulty in holding them for longer tasks. This plane was likely an experiment by Towell to address that issue. Body of this mitre is a little different as well: sidewalls bent at the front instead of dovetailed, and a brazed joint is placed at the rear of the the plane, making the sides one continuous piece. This would have created a weakness if users rapped the back of the plane.

This Towell mitre made quite a splash when it came to auction, in January 1986. At the time, Towell was extremely rare, and it was not known that he had a fairly prolific output spanning five decades. There may be only two or three of this variation in existence. Photo by Bill Carter.

.

Robert Towell moved his name stamp from the middle to the front of the lever cap, in order to make room for the handle. Photo from ebay.

This dual handled Bradley mitre made by Robert Towell is an amazing plane. One can tell that Robert Towell thought it was a very special tool by making those handles on the bun and wedge each out of one piece of mahogany.

Joseph Bradley was a planemaker and factor working from 23 Old Compton Road in London. A Bradley rule was sold in a 2020 Stanley Auction. There is a little more on Bradley out there– Goodman’s 3rd and 4th editions have the following:

“Bradley, Joseph West St., Seven Dials 23 Old Compton St. LONDON <1798>

1798: Insurance Policy. Described as planemaker and broker. The insurance policy covered a shop and loft.”

This insurance policy would have been from the Sun Insurance Policies, which are not online, and require in-person review.

Bradley/Towell mitre plane, with dual handles. Handles, bun, and wedge made from single pieces of mahogany.

Then, going on to David Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools,” on page 300—No. 874—also appears with Towell features: extra long front infill, etc. This plane also has a Ward & Payne iron. The Ward & Payne partnership and trademark was made official in 1843, though an informal partnership likely existed before then. Payne was documented as making edgetools in the 1830s.

Most likely, this mitre plane would have been a special order, possibly from Joseph Bradley.

Towell’s Lever Cap

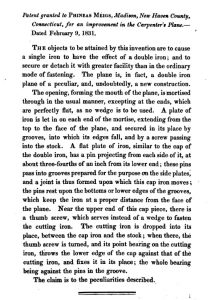

Description of Meigs’ Lever Cap Patent of 9 February, 1831, in “Repertory of Patent Inventions,” published in London, 1833.

Ideas around a lever cap for securing a cutting iron in a hand plane had been circulating well before the 1840s. On 9 February, 1831, Phineas Meigs, of Madison, Connecticut, U.S.A. registered a patent for a lever cap. Unfortunately, the original text of the patent as well as all the patent drawings were lost in the 15 December, 1836 Patent Office fire at Blodget’s Hotel Building which destroyed 10,000 patent documents. Later, 2,000 of these were recovered, but Meigs’ patent was not one of them. A description of Meigs’ Lever Cap was included in “Repertory of Patent Inventions,” published in London, during 1833. Since Meigs’ Lever Cap was not put into production, and there was no more patent registrations for lever caps in the United States until the second half of the 1840s, it is pretty clear that Meigs’ lever cap was not a direct influence on Towell, Cox, or Kerr. Most likely these early infill planemakers were aware of the general idea of a lever cap, which then coalesced with Joseph Fenn’s U.K. Lever Cap Patent on 12 November, 1844.

Meig’s Lever Cap invention, as described by Charles Holtzapffel, in “Turning and Mechanical Manipulation,” published in London, 1846; page 498.

Nevertheless, Meig’s lever cap patent was noticed by the famous tool merchant, Charles Holtzapffel, who described it on page 498 of “Turning and Mechanical Manipulations,” published in 1846. It was not clear if Holtzapffel observed an actual model of the invention, or whether he just read about it in “Repertory of Patent Inventions.”

Beechwood smooth plane, with Fenn patent lever cap. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, September, 2016.

Just because the year 1830 has been generally and arbitrarily associated with Towell does not imply that Towell’s lever cap was developed at that time.

This was not necessarily the earliest lever cap. Fenn’s Lever cap was patented in 1844, and this Towell mitre could have been made as late as 1863.

Born in 1790, Towell would have commenced work around 1810, but until late in his working life, Towell likely confined his efforts to traditional box mitre planes, rebate planes, and a few panel planes. In 1861, Robert Towell still declared himself as an “Iron Planemaker” in the U.K. census, with the help of his son Robert Jr. With that assistance and support, Robert Sr. would have plausibly worked right up to the 1863 death of his son. All told, its at least a dozen years longer than having stopped working before 1850 as previously thought. Robert Towell did not work in a vacuum: in late career, Robert Towell worked contemporaneously with iron planemakers such as Spiers, Kerr, Syme, Cox, Badger, and others.

Three Moon Mitre Planes, Cupid’s Bow bridge, post Gabriel type bridge, and early lever cap. Photo by Jim Moon, from the MWTCA Gristmill, December, 2001.

It is inferable that Towell’s innovations shown above–iron smoother plane, iron panel plane, lever cap, and experimental mitre plane– were introduced in the 1840s, 1850s, even early 1860s. This would have been around the same time that other makers began making lever caps and iron bench planes. Influence between makers was manifested in the 1850s; Joseph Fenn’s November 12, 1844 patent lever cap was adopted in various forms relatively quickly and widely. For example, a Moon mitre plane with lever cap (page 6) has been observed, and that would have been made before the closing of the Moon Tool Warehouse in 1848.

This Towell mitre plane with lever cap sold on Ebay Australia in July 2021. The late Towell mitre plane has a pentagonal lever cap screw, similar to the octagonal screws of George Kerr and Edward Cox:

The Towell mitre plane shown above, was dually signed: J.BUCK on lever cap, and Rt. TOWELL on front infill. Towell made the sidewalls of the plane with one iron plate, rather than the traditional separate front plate. In doing so, Towell made the toe with rounded corners and he made a welded seam at the heel of the plane.

A small number of later Towell mitre planes with this type of body construction have been observed, including some with a bridge and wedge.

Late Towell mitre plane with bridge and wedge, and continuous sidewalls. Photo by George Anderson, December, 2013.

Robert Towell: One of the Best Planemakers.

Towell mitre and rebate planes. Towell rebates that I have seen, do not have a metal keeper or bridge, like later rebate planes do, such as Spiers.

I. (John) Smith mitre planes:

John Smith was born in 1782, eight years before Robert Towell, which placed him as one of the earliest makers of English metal planes.

This Ward iron has a rebate style sneck cut into the side. It could have been done at any point in time that the plane was used. For a while, I had a replacement iron in this Smith mitre plane, without altering the wedge, having been somewhat turned off by this unusual ‘feature.’ After some time, I came around to the fact that the sneck is part of the history of this mitre, so I put it back in for good.

During the last decade, I have observed more than half a dozen I. Smith mitre planes, two of which were in the Russell Collection, nos. 886 and 887. All of those Smith mitre planes had a classic mitre plane profile, with dovetailed construction. Most I. Smith mitres had an early style bridge like the example shown above, but two I’ve observed had a shallow cupid’s bow cut into the bridge. One Smith mitre with cupid’s bow was depicted in David Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools,” no. 887, and the other sold on Ebay U.K. In addition to smaller mitres such as the 8 inch model, Smith made full sized mitres ranging 9 to 10 inches long, with two inch irons.

At the heel, the sidewalls have two bends compared to one on the smaller Smith plane shown above. Another full sized I. Smith mitre plane came up for sale on Ebay in April 2019.

An indication regarding John Smith’s age, was his use of “I” for “J” (John) for his proprietary stamp on his iron planes. Using “I” in this context was a practice that was ending by the beginning of the 19th century. For example, the spelling of edgetool maker “I. Sorby” (John) on their Sheffield plane irons was implemented in the late 18th century, and then retained in later stamps (“I. & H.”), as a tradition.

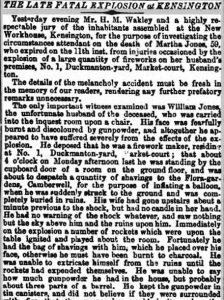

John Smith mitres, made in the early to mid-19th century, were somewhat old-fashioned when they were new. Smith also made iron rebate planes. Nigel Lampert in Through Much Tribulation Stewart Spiers and the Planemakers of Ayr estimated I. Smith’s rebate planes to have been made during the 1840s and ’50s. That estimation has been borne out after uncovering a random 1849 article on a fireworks accident in the London-based Evening Mail.

“John Smith, of 1, Holland-Place, metal plane maker…” from the “Evening Mail” on 14 September, 1849

In this fireworks accident, 59 year old Martha Jones was killed “at the 11th instant,” and her husband William Jones was grievously injured. A jury was assembled at the New Workhouse in Kensington. William Jones was involved in making firecrackers, and many of the rockets were set off in the fire, which took place at No. 1 Duckmanton Yard, Market Court, Kensington. Metal planemaker John Smith, was also partner with William Jones in fireworks making, as a sideline. Serving as witness, John Smith stated that William Jones was actively involved in making the explosives when the accident occurred. Jones denied that he was working with gunpowder just before the firestorm. Just five minutes before the explosion, John Smith had been in the house where the tragedy occurred. The jury returned a verdict of “Accidental death, resulting from the explosion of a large quantity of gunpowder.”

Original article from the London Evening Mail, 14 September, 1849. Other coverage included the Hampton Advertiser, and The Mechanics’ Magazine Museum, Register Journal and Gazette, 5 January, 1850.

Unmarked 9″ mitre plane with Smith features. Rear infill creosote treated beech, a cost saving decision.

William A. Fletcher, sawmaker and toolmaker, was located at 16 Leader St., Chelsea in the 1851 U.K. census. Most likely, Fletcher bought in John Smith’s mitre plane to retail it himself. William Fletcher remained at 16 Leader St. until his death in 1872. Chelsea adjoins Kensington on the south side. As late as 1912, William Robert Fletcher, was trading as a sawmaker at 69 Leader St. In around 1908 Leader Street was renamed Ixworth Place, but an old business such as Fletcher’s would have retained their old Leader Street stamps.

Fletcher Leader St. Chelsea 1 1/4″ iron found in unmarked thumb plane, circa 1910 with Norris characteristics. Tooltique.co.uk

Shown below are two I. Smith mitre planes: one is marked I. Smith, and has an 8″ length, with rosewood infill. The other is a 10 1/2″ Fletcher/Smith mitre plane with mahogany infill. Ward irons in both planes.

John Smith was born to Peter and Jane Smith in the small town of Bickerstaff, located in West Lancashire in 1782. Lathom, the place of baptism, was just a few miles from Bickerstaffe, and this was the only John Smith recorded as baptized in the immediate locale during 1782. Considering the sparse population of the area, this is likely the correct John Smith.

Duplicate recording of John Smith’s baptism 10 November, 1782. Bishop’s transcript at Ormskirk, Lancashire..

Bickerstaffe has had a population of around 1,100 in recent years. Based on the following description, Bickerstaffe was not a difficult place to leave:

Bickerstaffe may be described as an unpicturesque open country bare of woodland, with the exception of a few plantations mostly composed of birch tree, characteristic of moss land. Fields, divided by low hawthorn hedges are mostly cultivated. The country is waterless, with the exception of two small streams on the south, The farms and houses are considerably scattered and nowhere can be said to form a settlement of any size, The western half of the the township consists geologically of the upper mottled sandstone of the bunter series of the new red sandstone. By a fault running due north and south the middle coal measures are thrust up in the eastern half.

–A History of the County of Lancaster:Volume 3, Farrer and Brownbill, London, 1907.

Bickerstaffe scene. Photo from gunsonpegs.

Hunters in the Bickerstaffe area, which appears considerably more bucolic than the 1907 account. Perhaps a lot of trees have grown up in the last century.

In any case, it must have been difficult to make a living in Bickerstaffe in the early 1800s.

John Smith, 68, “Plane Maker,” at 4 James Place, Kensington in the 1851 U.K. census. Born in Bickerstaffe.

John Smith, who entered his trade as a “Plane Maker,” was living and working at 4 James Place, Kensington, during the time of the 1851 U.K. census. John Smith, 68, was living with his wife Elizabeth, 65, and son John Jr., 28.

A note on researching for John Smith. Honestly, there couldn’t be a more difficult name to research, and the information that I have rejected for lack of validation is voluminous. An example of this is the search for John Smith’s marriage to Elizabeth. John’s wife Elizabeth was born in Birmingham around 1786. Birmingham is halfway to London in a direct line between Bickerstaffe and London, and John Smith could have spent enough time in Birmingham to have married Elizabeth. There are a number of marriages between a John Smith and Elizabeth between 1802 and 1821 in Birmingham, but the omnipresence of both their names preclude selecting a document that is verifiable. John and Elizabeth could have also married in Lancashire, or London, and a myriad marriages between John Smith and Elizabeth are possible.

This church was right in John and Elizabeth’s neighborhood, and could have been their place of marriage. A John Smith and Elizabeth Iscum married at St. Mary Abbots in 1808, but this Elizabeth was born in London rather than Birmingham, and then she remarried in 1810. With an uncommon surname, Iscum was exponentially more possible to research than Smith.

John Smith married Elizabeth Iscum 17 January, 1808, at At Mary Abbotts Church, Kensington. Rejected.

And here is a baptism record for a John Smith Jr. in 1820 at St. Marylebone Church with John Smith Sr. and Elizabeth. John Jr. would have been born three years later, according the the 1851 U.K. census reporting, only marginally within parameters as far as the census is concerned. Record rejected, but not entirely ruled out.

Baptism of John Smith Jr., 19 Castle St. 13 November, 1822, at Saint Martin in the Fields Church, Westminster.

This baptism is in the right time period, and John Smith Sr. was of the correct class, but the job “servant” was not a perfect match. Castle St. and Crown St. were short and narrow slum roads that were replaced by Charing Cross Road in 1887.

Record saved for further evaluation.

Holzapffel & Deyerlein Wareroom at 64 Charing Cross (proper) c. 1821-1826. Image from Holzapffel.org

Holzapffel, the famous lathemakers, had an opulent showroom at 64 Charing Cross (proper) from 1819 to 1901. Extremes of wealth and poverty were characteristic of London, then and now. But especially then.

Similar research issues exist for a John Smith in the trade directories as well as the 1841 U.K. census. None of the entries are sufficiently definitive to warrant inclusion at this time. One ‘John E. Smith,’ age 20, “Planemaker (Apprentice)” appeared in the 1881 U.K. census at 11 Brighton St., Saint Pancras. In a current reference book, John E. Smith was identified as the same John Smith, previously located at 4 James Place in 1851. There is no known connection between these two planemakers.

John Smith, Cabinetmaker & Upholder, working from 8 Terrace, Kensington, in 1832. Sun Insurance Policy.

This 1832 Sun Insurance policy document for John Smith is compelling but unconfirmed. The problem with this John Smith insurance policy is that most of the other original sources of information for John Smith point to his being rather ‘down on heel.’ £500 was a great deal of money in 1832; adjusted for inflation, that would amount to £71,625 in 2023.

John and Elizabeth Smith’s son John Jr. was born in London circa 1823. Based on Smith’s early style dovetailed mitre and rebate planes, his metal planemaking began around 1823 or earlier.

After arriving in London, John Smith did not appear to wander far from his familiar corner of Kensington. Section of Edward Weller’s 1868 map of London, showing 1 Holland Place and 4 James Place in Kensington, where metal planemaker John Smith was based in 1849 and 1851 respectively. Before 1860, metal planemaking was still limited to a handful of makers, so there is no doubt that this John Smith is the individual who made the rebate and mitre planes considered here.

In Kensington, as late as the 1820s, many open fields were farmed. Market Court was already densely populated then.

“Kensington Improvements” was the site of No. 1 Duckmanton Yard, Market Court. Market Court was a Dickensian slum full of fire hazards and extreme poverty, quite the opposite of the upscale tony neighborhood that it is today. Building code violations abounded, including exposed wood siding over internal wood framing. Overcrowding led to many tuberculosis and cholera deaths.