© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

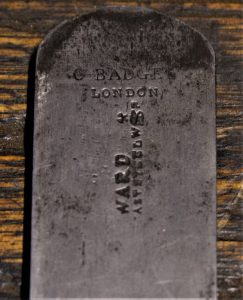

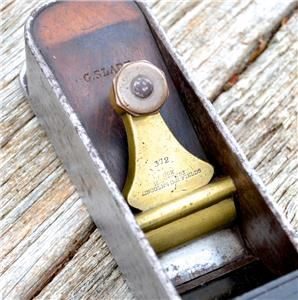

EDWARD COX PLANE AND LATHE MANUFACTURER

Cox mitre plane, 1840s, early lever cap, and characteristic octagonal lever cap screw. Photo from Ebay, 2014.

Edward Cox made some first rate planes, and he was an innovator: Cox was an early maker of lever caps.

Cox mitre plane; this example has a lever cap that was no longer pear-shaped. Possibly a later example. Photo by Jeff Warner January, 2022 (Facebook).

Cox mitre plane levercap, 15 Great Queen St. London. Steel thumbscrew. Photo by Jeff Warner January, 2022 (Facebook).

Additionally, Edward Cox experimented with eliminating the nut on cap irons and threading the cap iron itself, in order to clear the underside of the lever cap on his bevel down planes.

Cox’s octagonal lever cap screws typically had three rings of fine knurling: 2 on top, 1 underneath, revealing scrupulous attention to detail.

Cox was was not a well known lathe maker. I contacted lathe expert Tony Griffiths in the U.K., regarding Cox, and he was not familiar with Cox lathes. A small number of Cox planes survive, and an even smaller number of pictures of them are available.

The gunmetal bridge, with its ‘oversized’ cupid’s bow, is remarkably similar to same on the 8″ Moon mitre shown earlier.

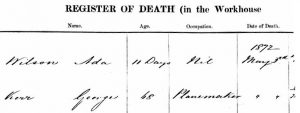

Edward Cox was born in Godmanchester, Huntingdonshire, on 11 June 1806 to Edward and Elizabeth Cox. Godmanchester is a small town about 17 miles northwest of Cambridge, U.K.

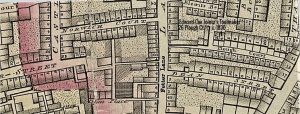

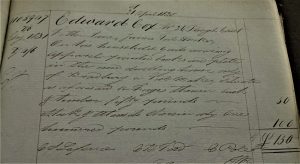

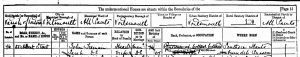

By 1830, 24 year old Edward Cox had established himself as a Joiners’ Toolmaker at 26 Plough Place, Fetter Lane in London. Cox shared these premises with another toolmaker by the name of Bradbury, and they had a forge on site there. Plough Place was about 5 blocks east of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. “Utensils” denoted equipment and tools, not knives and spoons.

Edward Cox, Joiners’ Toolmaker at 26 Plough Court, Fetter Lane, <1830-1831>. Sun Insurance Document.

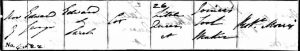

Christening of Edward and Sarah’s son, Edward George 9 November 1834. “Joiner’s Tool Maker; 26 Little Queen St.”

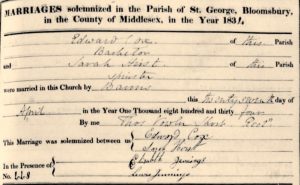

In 1834, Edward and his new wife Sarah Hirst had moved to 26 Little Queen St., just down the block from Ann Moon’s Tool Warehouse. The recurrence of the street number 26 was a coincidence. Edward and Sarah married at Saint George’s Church on 27 April, 1834. St. George is on Bloomsbury Way, about 4 blocks west of Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Edward Cox married Sarah Hirst (1805-1876) on 27 April, 1834, at Saint George’s Church in Bloomsbury.

Susanna Cox was Baptised at Saint Giles in the Fields. on 12 April, 1840. Edward Cox, “Tool Maker,” was still living at 26 Little Queen Street.

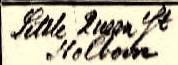

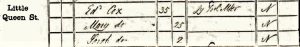

Edward Cox, “Journeyman Toolmaker,” [26] Little Queen St., Holborn, in the 1841 U.K Census. The census-taker confused his wife Sarah, with a 2 year old child, Mary.

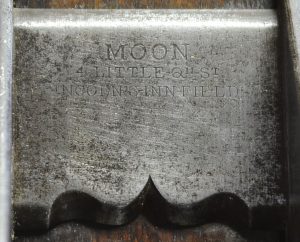

Edward Cox moved his business and residence from 26 Little Queen Street to 15 Great Queen St. Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1842.

Edward Cox, Tool & Plane Maker, 15 Great Queen St. Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1843 Robson’s London City Directory.

Matilda Cox was baptised at Saint Giles in the Fields, on 7 June, 1846 . Edward Cox, “Tool Manufacturer,” was living and working from 15 Great Queen St.

With a cupid’s bow bridge in iron, rather than gunmetal, I would estimate this example could have been made as early as the 1830s; because the stamp on the bridge omitted the Lincoln’s Inn Field address, this plane may have preceded 1834. The wedge is similar in shape to the 10 1/2″ inch long Moon mitre plane.

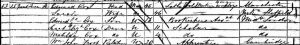

Edward Cox and his family, 1851 U.K. census. 15 Great Queen St. He declared himself a “Lathe Tool Maker; [who] employs four men.”

Edward Cox’s entry in the 1851 Kelly’s London P.O Directory. First year for Lathes in P.O. Directories.

Cox mitre plane bridge with small cupid’s bow. This stamp may predate Cox’s Lincoln’s Inn Fields mark.

It is true that so many cupid’s bow bridges look similar, and while these two are not identical, they are both ‘undersized’ for their spaces in a like manner. It is also important to look at the entire construction of the plane to do a fair comparison. But there are really not enough examples of these two rare makers in order to establish clear attributes for each. Was there a Moon and Cox connection?

COX 15 GREAT QUEEN ST. LINCOLNS INN FIELDS stamp on bridge of panel plane. No. 640. Photo from British collector.

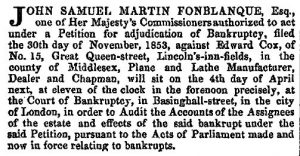

15 Great Queen St. was right around the corner from Ann Moon’s Tool Warehouse at 4 Little Queen St. Having been in the right place at the right time, Edward Cox may have been a supplier of mitre planes and other tools to the Moon tool warehouse. In several legal publication entries, Cox was described as a “chapman,” (i.e., cheap) which was an archaic English term for a merchant who bargains. Such a description was indicative of a willingness to sell his tool products wholesale to the trade. Indeed, the loss of business from the closing of the Moon Tool Warehouse circa 1848, may have played a role in forcing the bankruptcy of Edward Cox in 1853.

Some collectors avoid duplications, but I feel that much can be learned from observing two examples of the same ‘model’ such as we have here. This is especially true with a maker like Edward Cox, whose bespoke planes are hard to come by today.

As you look inside these two planes, you can see that the mouth on the 15 Great Queen St. example is slightly longer side to side than the Cox London example, and the Greaves iron is a commensurate increment wider as well. Edward Cox lived and worked out of 15 Great Queen Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields from 1842 to 1855, but he may have retained this stamp for Cox infill planes made in Sheffield into the 1870s. Cox still referred to himself as a “London Tool Manufacturer” as late as 1873!

Some of Cox’s infill planes were numbered, but many were not; they could be serial numbers. The 15 Great Queen St. mitre was marked 368 on the front flange, and also on the wedge, and some of the other Cox planes shown here also have numbers. Cox, like the other planemakers, would have had drawings, patterns, and templates, so that he could duplicate his various ‘models,’ but ultimately these tools were handmade, so there was still variation between examples. For example, these two planes have noticeably different front infill patterns.

Heels of Cox mitre planes, with snecks, strike buttons, and wedge scrolls. Ward & Payne iron (l.) Isaac Greaves iron (r.).

Edward Cox entry. From “The British Colonies: their History, Extent, Condition and Resources,” by Robert Montgomery Martin, published 1851.

19th century basic Holtzapffel Lathe, likely similar in scale to a Cox lathe. Photo from lathes.co.uk

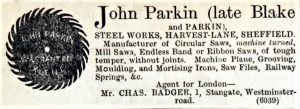

“Improved planes” were likely the Cox bench planes made in iron instead of wood. Along with Holtzapffel, Cox was listed under “Lathe and Toolmakers,” in Kelly’s London Trade Directory for 1851.

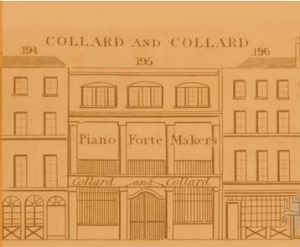

Bankruptcy of Edward Cox, 15 Great Queen St, “Plane and Lathe Manufacturer, Dealer and Chapman,” 30 November, 1853. London Gazette.

With four employees and a notable address, Cox must have had a fairly high overhead. In subsequent years, 15 Great Queen St. was home to prominent lawyer, Charles S. Parker, the Arliss Printing Company, and the Masonic Depot.

1833 represented the year of establishment for the business. This is based on the numbers given for a multitude of listing entries.

After his bankruptcy in 1854, Edward Cox moved to Sheffield.

In the 1861 U.K. census, living at 129 Tom Cross Lane, Sheffield. Edward Cox was listed as a “Manager of machinery for Tool Maker (Plane Making).”

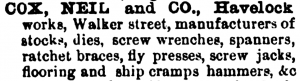

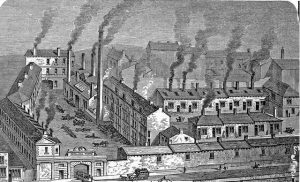

Because of its proximity and prominence, I have pointed out the large “Spital Hill Works” of the Sorby edgetool making dynasty.

Upon moving to Sheffield, Edward Cox become a “Manager of machinery for Tool Maker (Plane Making),” in a partnership with Charles Neil (1834-1909). Edward Sr.’s son, Edward George, born 1834, was a “Planemaker,” probably under the employment of his father. Along with Lathes and Engineers’ Tools, Edward Cox and his son made planes; these may have been additional infill planes that retained his London marks. There are no Cox planes, that I know of (of any type), that bore a “Cox , Neil & Co. Sheffield” mark.

Cox and Neil, in “The International Guide to British and Foreign Merchants and Manufacturers,” Published by Ingoldby and Lamb, London, 1872.

Edward Cox, declared his job as an “Engineer’s Toolmaker,” in the 1871 U.K. census, living at 6 Cranworth Road, Sheffield.

Brightside, Sheffield. Heavily industrial at the time.

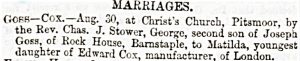

At the end of his life, 20 years after leaving London, Cox still referred to himself as a “London tool manufacturer” in his daughter Matilda’s 1873 wedding announcement. Edward’s widow, Sarah, age 71, was buried next to him in Burngreave Cemetery (grave no. 3, sect. Y2), on 6 June, 1876.

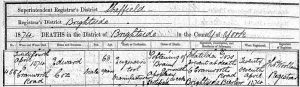

Edward Cox’s burial was done 28 April, 1874 in Burngreave Cemetery in Sheffield. “Cons.” is an abbreviation for the grave having been consecrated. Henry Taylor performed the ceremony.

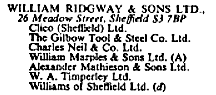

Seventy five years later, the Charles Neil & Co. Ltd. company had a description of their business that was remarkably similar to that of Edward Cox’s in 1851. Charles Neil & Co. Ltd. continued to trade into the 1970s, under the ownership of William Ridgway & Sons, Ltd.

William Ridgway & Sons, companies owned (just before Record-Ridgway merger, 1972). From ‘Who Owns Whom [U.K.]” Published by O.W. Roskill, 1971.

Charles Neil Ltd., entry in “Kelly’s Directory of the Electrical Industry and Wireless and Allied Trades,” 1926.

The following four photos show an early Cox panel plane that was sold on Ebay in February, 2023:

During February 2023, a Cox mitre plane, with a stamp that did not include “Lincoln’s Inn Fields” was also sold on Ebay:

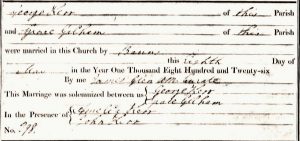

GEORGE KERR MITRE PLANES

In Antique Woodworking Tools, published 2010, David Russell wrote that “very little is known about Kerr.”

Since Kerr’s planes were stamped without his first initial, not even that was known, which posed an obstacle to research. In 2015, one James Kerr was floated as the possible planemaker. In Goodman’s British Planemakers, 3rd edition, 1993, only four Kerr metal planes had been reported. Russell’s collection of Kerr planes included a dovetailed panel plane, a smooth plane, a rebate plane, and two thumb planes.

Williams London Trade Directory 1864. With this directory, a firm working location, date, and given name for George Kerr, planemaker has been established.

George Kerr did not live and work in isolation; he was influenced by his contemporaries, and he influenced makers who followed. Kerr’s early lever cap has an outline which is similar to that of Robert Towell, and his lever cap screw is octagonal, like that of Edward Cox. The original owner carved a crucifix into the front infill. It is part of the tool’s history.

By process of elimination, the maker of this thumb plane can also be attributed to George Kerr, although creation by an unknown craftsman cannot be ruled out. There were only a handful of makers who produced thumb planes, and only three makers used dovetailing rather than casting to build them (actually 4, if one counts the less than handful of examples of the Holland hybrid thumb/chariot plane). They would be Stewart Spiers, George Kerr, and very early Thomas Norris (Thumb plane No. 12). Of these, only Kerr made them with a separate heel plate, like the one shown here. Making this separate heel plate with the extra dovetails increased the amount of labor for each plane. On the thumb plane, the dovetails were practically invisible on the sides, and only apparent at the back, probably as a result of heel strikes. There are other shared similarities between these two planes: 1. unusually long rear flanges, 2. thin head on strike buttons (damaged original on thumb plane was thin also), 3. half round housing for lever cap/bridge fulcrum of similar diameters, and 4. sidewalls made of atypically thin (for the period) wrought iron.

Early panel plane by George Kerr. Kerr used blunt handmade screws to attach the overstuffed infills, so at least the screws predated 1849 or so. Two other makers used a lever cap with a similar profile: Charles Badger, and Edward Cox. In the case of Kerr, he used at least two different pattern lever caps, as seen on the Kerr mitre plane above. Another Kerr panel plane can be seen at the bottom of this page. The shape of the body is slightly different, with sharp corners at the toe.

A personal note: I was the frustrated underbidder on this Kerr mitre plane in the 2016 Wright Marshall Auction!

George Ker (original spelling) was born to Andrew Ker and Jane Wright, in Aberdeen. Scotland in 1805, and baptised at Saint Nicholas’ Church, Aberdeen, on 19 March, 1805.

George Kerr, listed as a “Cabinet-Maker,” Kingsland Place, Aberdeen, Scotland in the 1827 P.O. Directory.

George Kerr had an older brother, Andrew Jr., born in 1803, and a younger brother, John Henry (1807-1860), who joined George in London. John Henry married at St. George’s Church in the East, the same church that George attended. John Henry Kerr worked as a mariner.

These two documents are in chronological conflict, but they may both be for our George Kerr. The City/Trade Directory staff did not always do a great job keeping up with the moves of their inhabitants. This 1827 Aberdeen listing could have been a carry-over from 1825 or early 1826. Since his second marriage was also celebrated at St. George, Hanover Square, and since Saint George, Hanover Square was the district ward for George Kerr in the 1841 U.K. census, it lends credibility to the likelihood that this was a valid document for George Kerr, metal planemaker.

Grace and George lived on Francis Street in 1831.

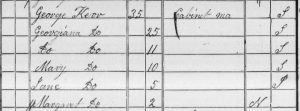

George Kerr, “Cabinetmaker,” and his younger siblings/cousins on Neat House Row, Millbank in the 1841 U.K. census.

During the time of the 1841 census, George and a number of his younger siblings or cousins lived at Neat House Row, in the Millbank area of London. Neat House Gardens were a source of fresh cauliflowers, cabbage, artichokes, asparagus, beans, spinach and radishes for London in the 17th and 18th centuries. Fruit was also cultivated. With alluvial soil, a high water table, and plenty of manure, the land was very arable. By 1841, however, development was encroaching on this area, and market gardeners were force to move further from London.

The letter “S“ represents place of birth: Scotland.

George Kerr, listed as a “cabinetmaker,” married Harriet Bulbeck on 13 April, 1845, who also lived at Saint George, Hanover Square.

George Kerr’s father was Andrew which agreed with the baptism transcript.

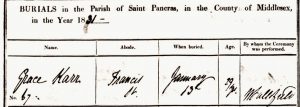

George Kerr worked as a “pianoforte hammer rail maker,” at 4 Cleveland Street. London P.O. Directory, 1850.

There is an alternative possibility that the “pianoforte hammer rail” they were referring to, is presently designated as the main action rail, upon which the hammer assemblies are mounted. Making the main action rail would require more precision than a hammer rest rail, and would utilize the requisite skill for specialization.

Collard & Collard piano; one of their facilities was located at 194-196 Tottenham Court Road, London at the time of researching for Tallis’ Street Views of London (1838-40). Pianos were previously called Clementi, for the former factory co-owner, famous pianist and composer, Muzio Clementi (1752-1832). Clementi sonatinas are still much used by piano teachers today.

Here is an example of Clementi’s later work:

Didone Abbandonata – Piano Sonata in G minor, Op. 50, No.3 was the last sonata published by Muzio Clementi in 1821. It was titled after Metastasio‘s often-set opera libretto of the same name, and Clementi sought to tell the tragic story of Virgil‘s heroine through the voice of the piano. Pianist Maria Tipo is one of the greatest performing artists of our time.

The major tool London tool dealer, George Buck was located at 245 Tottenham Court Road. Some Kerr planes have been noted with Buck cutting irons.

In the 1861 UK census, the Kerrs were still living in 24 Buckingham Place in Marylebone, and had a ten year old son, Frederick. George Kerr described his job as “Gunmetal manufacturer” in 1861.

Ten years later, in the 1871 census, George Kerr was an “Iron plane maker,” with assistance from his son Frederick.

![]() Planemaker George Kerr’s advertisement for additional labor at 36 Store St. (“Pianoforte Case Makers”) in the Clerkenwell News, September 1, 1865.

Planemaker George Kerr’s advertisement for additional labor at 36 Store St. (“Pianoforte Case Makers”) in the Clerkenwell News, September 1, 1865.

Shown below are two Kerr rebate planes, and one Kerr panel plane, owned by collectors George Anderson and D. S. Orr.

Kerr panel plane below, right, was no. 1090 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell. In this photo, the strike button was removed.

Four Kerr infill planes, rebate, two smoothers, and a shoulder plane. The larger smoother and shoulder planes are cast; the rebate and smaller smoother, dovetailed. From collection of George Anderson, photo June 2017.

Shown below are four images of a Kerr smoother: two features of this plane that I appreciate are the Cupid’s Bow on the bridge, and the ‘hot dog’ front tote, which is overstuffed. Before George Kerr was better known to collectors and researchers, some in this space estimated Kerr’s working years as earlier than they actually were. That is probably why this Kerr smoother has a Weldon iron, which pre-dated Kerr, with a time range of c.1780 to c. 1835. Kerr often used Ward or Sorby irons dating from late 1830s to the early 1870s.

This cast iron smoother by Kerr (stamped on top edge of gunmetal bridge) has overstuffed beech infills. The I. Sorby iron is rounded at the top, a rather old fashioned practice for bench planes by the middle third of the 19th century, but it was something that Kerr did on a number of his plane irons.

Below are two more images of this same Kerr plane:

This next Kerr smoother was sold by Steve Jacobs at tooltique.co.uk. It has a dovetailed body, with open toe and heel.

This Kerr smoother has a bridge with characteristics that are instantly recognizable as Kerr’s. This bridge can be found on Kerr panel planes as well.

The four photos below show an unmarked Kerr Mitre Plane; there are many more unmarked Kerr planes than there are marked Kerr planes. One of the many interesting aspects of studying and collecting antique tools is the process of discovering a toolmaker’s ‘standard practice,’ and then exploring the inevitable variations within that maker’s output. This particular mitre plane has a front infill and moulding that is very similar to the front infill on the named Kerr mitre plane with lever cap that is shown in this section on Kerr. Also, the gunmetal bridge is similar to a number of other stamped Kerr bench planes, and in particular, may be the same casting as that shown on the Kerr smooth plane from the Coopers’ Tool Museum.

On the other hand, there are some key differences in the way these two Kerr mitre planes were constructed. In general, the Kerr mitre plane with lever cap shows more refinement and probably took more of Kerr’s time to make. This makes sense, considering that when this plane was made, 1840s to 1850s, a lever cap was a relatively new invention, and special, in a way.

The wedged Kerr mitre plane has 3 long dovetails on each side: 1 dovetail in front of the mouth, and 2 dovetails behind the mouth. The sole is joined at the mouth with a modified butt joint that appears to have a small triangular shaped wedge driven in after assembly. Iron stock for the sidewalls is of normal thickness for the period, and the heel was bent in a single horseshoe bend. Flange extensions on the toe and heel are short, resulting in a plane 7 7/8″ long. And the sole is 2 1/4″ wide, with a 2″ iron.

The Kerr mitre plane with a lever cap has 5 shorter dovetails on each side: 2 dovetails in front of the mouth, and 3 dovetails behind the mouth; the sole is joined at the mouth with a tongue and groove joint. Sidewalls of the plane are made of unusually thin iron stock, and sides do not appear to be linished. The heel was bent in two separate bends, similar to those made by Robert Towell. Flange extensions on the toe and heel are long, resulting in a plane 9″ long overall. This plane is 2″ wide, with a 1 3/4″ iron.

Kerr Mitre Planes, with similar front infills, and thin cheesehead screws at the heel, also typical of Kerr.

Both planes have survived well; the wedged Kerr mitre plane has seen more use and more corrosion. However, the wedged example still has a tight mouth, and after 180 years, all the dovetails and joints are still tight, with the exception at the right side of the mouth, and that is an unforgiving photograph. Structurally, it has held up almost as well as the Kerr mitre with lever cap, so a case can be made that the number of dovetails does not necessarily reflect on overall quality. After all, many of Thomas Norris’ mitre planes also had three dovetails on each side. And both Norris and Spiers came to use the butt joint at either side of the mouth to join the front and rear sole plates on some of their later mitre planes.

I. TREMAIN, PLANEMAKER

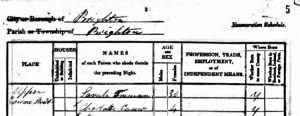

I. Tremain was included in British Planemakers Since 1700, 3rd edition, by Goodman and Rees, and BPM4. In those volumes, a mark was recorded for this maker: “I. TREMAIN; BRIGHTON.” No dates were given. Presumably the stamp was on a wooden plane.

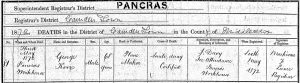

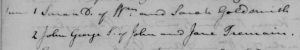

John George Tremain was baptised on 2 June 1805, at Saint Mary’s Church, Portsea, Hampshire, and his parents were John Tremain (1775-1836) and Jane (Jenny) Gillard (1785-1863).

John was the eldest of at least 10 children of this couple. Jenny Gillard and her family were from the Portsmouth area on the South coast of England, while John Tremain Sr. and his family were from London. John and Jenny lived in Portsmouth until 1819, when the Tremain family moved to Mile End, Old Town, London. John George likely moved with the family as he was only 14 at the time.

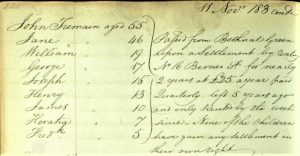

John Tremain Sr was a cabinetmaker, and almost all of his sons became cabinetmakers as well. Plying that trade did not necessarily shelter John and his family from hardship, however. The Tremains were recorded in the Bethnal Green Poor Law Removal and Settlement Records on 11 November, 1831:

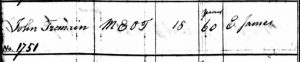

John Tremain Sr., age 55, in Bethnal Green Poor Law Removal and Settlement Records, 11 November, 1831.

Because John George, age 26, was no longer living with his parents in 1831, it was fairly likely that he had already left for planemaking work in Brighton.

By the time John George was an adult, and had finished his apprenticeship, John George moved back to the South coast, settling in Brighton. Most likely, John George set up shop as a planemaker in Brighton in the late 1820s. On 2 October, 1835, John George Tremain married Sarah Best in Hove (Brighton) Sussex. At the time of the 1841 U.K. Census, John and Sarah were living on Upper Edward Street in Brighton, and John George was working as a “Planemaker.”

For the years 1840, 1841, and 1842, John Tremain was listed on Upper Edward Street in Brighton in the Electoral Register.

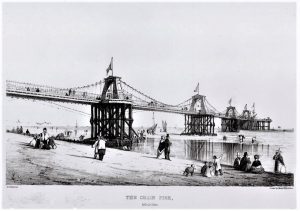

The Chain Pier, in Brighton, England, 1845. R. H. Nibbs, printed by C. Moody, 25 High Holborn circa 1845.

Edward Street was a couple blocks from the ocean, running parallel to the shoreline. 1888 Brighton Ordnance Survey.

This mitre plane was owned by John George’s brother, Frederick Tremain (1828-1908). Frederick was a cabinetmaker for all of his working life.

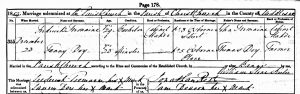

Frederick Tremain, cabinetmaker, married Fannie (Francis) Doy, on 23 December, 1854 at Christ Church, Middlesex, London.

John Tremain Sr., deceased, had been a “cabinetmaker.”

Max Ott (1926-2009) also possessed this plane, and that is a good detail to spot at auction. He had impeccable taste.

Sometime before 1851, Edward, Sarah and Charlotte left Brighton, and moved to Kentish Town (Saint Pancras), London. John George made a career switch from planemaking to pianomaking and started work at Collard & Collard Piano Company.

It is unknown whether or not John George Tremain continued to make planes while in London, but if this mitre was created new for Frederick, he would have finished his apprenticeship around 1850. The plane could have been made from as early as the late 1820s and as late as 1850. The features of the mitre plane, and the one line stamp of William Ash on the iron suggest earlier manufacture.

I suspect that John George kept this mitre plane for his own use at Collard & Collard, and when he passed away in 1882, the plane went to Frederick, who continued to work right up to 1908.

John Tremain, entered as “Pianoforte Case Maker,” 3 Upper Hartland Rd., Kentish Town. 1861 U.K. Census.

John Tremain, listed as “Pianoforte Case Maker,” 12 George St., Saint Pancras, in the 1851 U.K. Census.

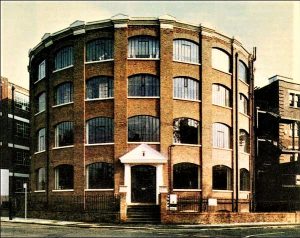

John George Tremain likely started working on pianos in the newly constructed Collard & Collard Piano Factory at 12 Oval Road, Kentish Town (Camden Town) only to see it burn down less than one year after it was built.

The windows were typically large and numerous, in order to take advantage of as much natural lighting as possible.

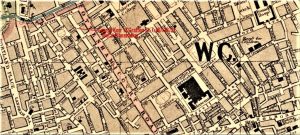

Collard & Collard is the circular building at the corner of Oval Road and Gloucester Crescent.

The other buildings, marked “Pianoforte Manufactory,” were also part of Collard and Collard. They were used for timber and veneer storage, wood turning, glue boiling, fret cutting, key weigh-off, and stringing.

From “Curious Kentish Town” (Five Leaves Publications, £9.95) by Martin Plaut and Andrew Whitehead:

Camden Town established itself as a major piano manufacturing centre in the nineteenth century, drawing industry away from Fitzrovia, because of the ease of transporting timber by canal, rail and road. It was said that every street in north London contained a piano works, and in many parts of Camden this was literally true. Between 1870 and 1914 Camden was the centre of the world’s manufacture of pianos which were sent around the globe. There were around one hundred in total. None now remain, although Heckscher & Company – which only in recent months moved out of 75 Bayham Street in Camden – has been supplying piano parts since 1883 and still does.

The most magnificent piano warehouse is to be seen at 12 Oval Road. It is the circular building constructed for Collard & Collard in 1852. This building replaced a similarly shaped one, which was destroyed by fire a year after it was built.

With fifty-two bays, it was built around a central open well, to allow pianos to be hoisted from floor to floor during manufacture. The lowest floor was used for drying, the next for upright pianos, the second floor for cleaning, the third for polishing the cases and those above for ‘belly’ manufacture and finishing off. Collard & Collard were the oldest of the piano manufacturing firms of the St Pancras area, having patented a form of upright ‘square’ piano in 1811. Today their former manufactory houses offices.

John Tremain, reported his trade as a “Pianoforte Case Maker,” living at 14 Lewis St., Kentish Town., in the 1871.U.K. Census.

Kentish town street locations for J. Tremain: Hartland Rd (formerly Upper Hartland Rd), 1861; Lewis St., 1871; Hawley Rd., 1880. London 1893 Ordnance Survey.

John and Sarah did not move from their familiar neighborhood in Kentish town from at least 1861 until they left London in 1881.

The round building in the upper right was the Rotunda Organ Works, built 1866, where Henry Willis and his artisans made organs, including “The Voice of Jupiter” for the Royal Albert Hall.

John Tremain entered himself as a “Pensioner of Collard & Collard, Pianoforte Makers, living at 55 Albert St., Portsea Island. 1881 U.K. Census.

Shortly before the time of the 1881 U.K. census, John George and Sarah moved to Portsea Island, close to their respective birthplaces, Hants, Portsea, and Arundel, Sussex.

In order to be eligible as a pensioner, John George Tremain must have worked a long time for Collard & Collard–most likely he worked there for his entire stay in London, 1851 to 1880.

Portsea Island was called “The Common” until 1792. The area was full of crime, and there was much disease as well, especially cholera. Portsea’s economy was dependent on the British Navy, and went through boom and bust cycles, depending on whether it was wartime or not. Especially war with France. Regardless of John George and Sarah’s decision to move to Portsea near the end of their lives, they were probably (marginally) better off for living in Kentish Town all of those years.

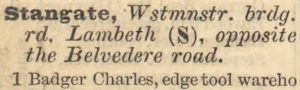

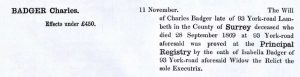

CHARLES BADGER, EDGETOOL WAREHOUSE

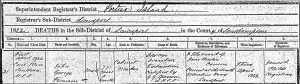

Charles Badger was born 28 April, 1817, in Longborough, Gloucestershire, to Joseph and Elizabeth Badger.

Birth dates for early British metal planemakers within this website range from 1731 (John Sym) to 1817 (Charles Badger). In chronological order, the next planemaker, Stewart Spiers (1820-1899), had a career which extended into a later period.

Isabella and Charles were a widow and widower respectively. Charles lived in St. Pancras previous to his 1843 marriage. Edward Phillips, Isabella’s father, was declared an “Ironmonger,” which proved to be an influential role for their future. I believe his example may have led Charles Badger to set business goals higher than that of a solitary self employed tool maker.

The mystery that was Galpin:

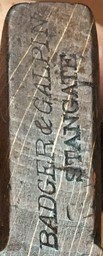

As early as 1846, Charles Badger went into business with Galpin, although Charles did not report that in his 1851 U.K. census entry.

“Galpin” was a rather transitory figure, who appeared on the scene as an early partner of Charles Badger, and then left without much of a trace. I have yet to locate a definitive London Trade Directory entry for Galpin independent of Badger, so we are left with only the 1852/53/54 entries for Badger & Galpin. Ar.clarence, on Pinterest has listed a Galpin (no first name or initial) as a “Tool Agent” in an 1856 London City Directory, but I have not been able to find out which London City Directory that might be. I do have access to the 1856 London Post Office Directory, but there was no Galpin listed as a “Tool Agent,” or anything similar.

The surname Galpin was not common. There were three allied tradesmen with the last name Galpin, who lived within commuting distance of Stangate Street during the early 1850s. I will list all of them, give a brief synopsis of their biographies, and then review the pluses and minuses around the possibility that they are the ‘right’ Galpin.

1.-Elias Galpin (1809-1884) was listed as a “Cabinetmaker” in the 1841 U.K. census, “Pianoforte Maker; Case Maker” in the 1851 U.K. census, and “Pianoforte Maker” in the 1871 and 1881 census. In 1841 and 1851, Galpin was located at 11 Great Pulteney Street, Covent Garden, and in 1881 at 30 Rawlings Street in Chelsea, London.

Elias Galpin, “Pianoforte Maker; Case Maker,” in the 1851 U.K. census. 11 Great Pulteney Street, Covent Garden.

2. Charles Galpin (1813-18??) was born in Dorset, and moved with his family to Bermondsey after 1841, but before 1847. Charles listed his profession as a “Carpenter” at 13 Blandford Terrace, Bermondsey, in the 1851 U.K. census. After 1851, it was unclear what happened to Charles, as there was no credible documentation for Charles Galpin after this time. Charles was included in several hypothetical family trees where he ended up alternatively in the U.S.A., or Australia after 1851.

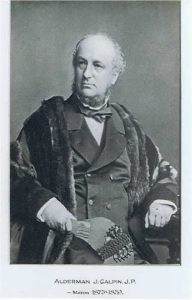

3. John Galpin (1824-1891) was born in Oxfordshire, and moved with his young family to 26 Doris St., Lambeth in 1846, to work for a “building company”. John declared his occupation as a carpenter in the 1851 U.K. census, and in 1854 he returned to work in Oxford as a Surveyor to the Paving Comissioner of Oxford. John Galpin, went on to work in many arenas, including auctioneer, real estate developer, and two stints as Mayor of Oxford, in 1873-4 and 1879-80. He also designed a bridge in Oxfordshire.

As a “Pianoforte Case Maker,” Elias Galpin was doing the kind of work most compatible with the nature of work that Charles Badger was producing. At least one other researcher has concluded that Elias Galpin was Badger’s early business partner. A problem with Elias Galpin was that he already had a job, and his 1851 census entry was for piano work, with no mention of “Tool Agent,” or merchant. This does not preclude the possibility that Elias’ work for Badger may have been part time, or after hours, but that would not seem to merit billing as the business partner of Charles Badger.

Charles Galpin’s only eligibilities were his vocation as a “Carpenter” in the 1851 U.K. census, and his proximity to Stangate Street, Lambeth, by living in Bermondsey. The fact that after 1851, there was no reliable paper trail for this Charles Galpin, diminished the possibility that he worked with Charles Badger.

John Galpin would have only been 22 when he moved his young family from Oxford to Lambeth in 1846. And 1846 could well have been the time when Charles Badger hired John Galpin. Badger would have seen in John Galpin, a high intelligence, and lots of potential. This became evident with the myriad enterprises that John Galpin engaged in later in his career. And John Galpin’s multi-faceted capabilities, would have enabled him to make the transition from carpenter to tool maker/merchant as a young man. In 1854, the exact year of the dissolution of the partnership between Badger & Galpin, John Galpin left Lambeth to find employment at the City of Oxford. Also, the address of John Galpin was closer to Stangate than either Covent Garden or Bermondsey.

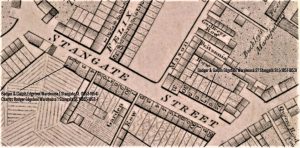

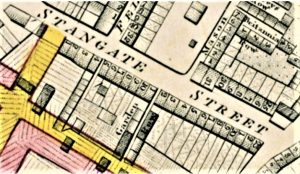

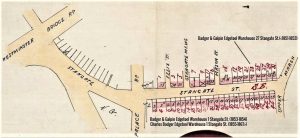

Badger & Galpin, Watkins Commercial & General London Directory Map (1852). 27 Stangate St., and 26 Doris St.

Badger & Galpin early smooth plane, circa 1851-1854, 27 Stangate St. Charles Badger’s home and shop was 27 Stangate St. at the time of the 1851 U.K. census, and no. 27 was a block East of 1 Stangate St.

Williams left 30 Stangate Street in the early 1840s; the proximity to Badger at 27 Stangate was a coincidence. No known connection.

“Badger & Galpin Edgetool Warehouse, 27 Stangate St, Lambeth” Kelly’s London P.O. Directory 1852.

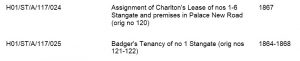

Badger & Galpin, “Edgetool Warehouse,” 1 Stangate Street, Lambeth. 1854 London Post Office Directory.

Badger & Galpin moved their shop to 1 Stangate St., sometime before the 1854 London P.O. Directory (“Badger & Galpin Edgetool Warehouse”) was published.

Before 1855, John Galpin had left the partnership, and only Badger was listed at 1 Stangate, where he remained until his 1868 move to 93 York Road.

Badger was keen on expanding his business, and clues around this, were his search for a shop foreman, as well as his proprietary description as an “Edgetool Warehouse,” or later, as a “Tool Dealer.”

Here is direct evidence that Charles Badger actually did run an “Edgetool Warehouse.” This ad also ran in The Engineer, on 2 July 1858.

The Builder was a journal of architecture published in the UK from 1843 until 1966.

The following four photos come from the outstanding collection of George Anderson, and they show three small (~4 1/4 to 5 inches) Mitre Rebate planes made by Charles Badger. This was a unique design invented by Badger.

Charles Badger (1817-1869) lived with his wife Isabella at 1 Stangate St. in Lambeth, and reported his occupation as ” Master Tool Maker” for the UK census in 1861.

In the 1860s, Palace Road was moved a block east, and renamed New Palace Road. This may have played a role in Charles Badger’s relocation to 93 York Road. West of Palace Road, St. Thomas’ Hospital was being built, also in the 1860s.

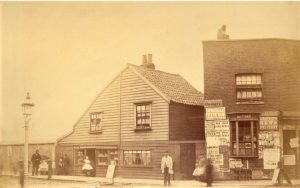

Elevation of the South side of Stangate. St.,with post-1881 street numbers. From British History Online.

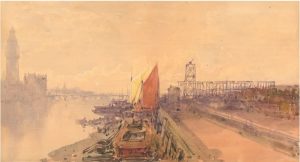

This may very well have been close to the view from 1 Stangate St. ; 1 Stangate was on the South side of Stangate.

In this photo you can also see St. Thomas’ Hospital, and through the haze, Westminster Bridge. The Clock Tower (Elizabeth Tower) with Big Ben, stands near the western side of the river Thames.

Inclusion of Charles Badger at 1 Stangate St. circa 1864-1868, in the Saint Thomas Hospital Archives would give indication that Charles Badger was likely compelled to relocate. The former Stangate Street numbers given do not align with any of the maps I have seen, and make no sense to me. Unless they were former Palace Road numbers?

Saint Thomas’ Hospital and Albert Embankment Construction. Watercolour by William Roxby Beverley, c. 1869.

None of the old Stangate neighborhood was visible in this image from the mid-20th century.

Charles Badger was still at 1 Stangate St. during the information collecting for the 1867 London Trade Directory.

Last year for Badger at 1 Stangate, which was confirmed by the St. Thomas’ Hospital Archives.

Badger’s first year (1869) at 93 York Road.

This was Charles Badger’s final listing entry. Isabella was still living there.

If Charles Badger had lived a full life, he would have been credited as one of the major infill planemakers in the 19th century. Even so, Badger exerted significant influence on Holland and Norris.

Charles Badger’s grave site can be be viewed here.

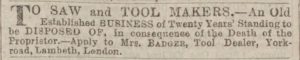

Here are some sources regarding the sale of Charles Badger’s shop at 93 York Road, Lambeth.

Sheffield Daily Telegraph, March 19th 1870:

To Saw and Tool Makers–An old established business of twenty years’ standing to be disposed of, in consequence of the Death of the Proprietor–apply Mrs.[Isabella] Badger York Road Lambeth London.

To Saw and Tool Makers–An old established business of twenty years’ standing to be disposed of, in consequence of the Death of the Proprietor–apply Mrs.[Isabella] Badger York Road Lambeth London.

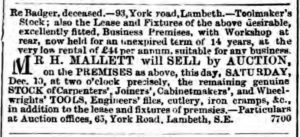

“South London Chronicle,” December 10th 1870:

Re: Badger, deceased 93 York Road Lambeth–Toolmaker’s Stock; also the lease and fixtures of the above desirable, excellently fitted. Business Premises, with workshop at the rear held for the expired term of 14 years at the annual rental of 44 GBP.

Mr. Mallet will sell by auction on the premises as the above on the 10th the remaining genuine stock of Carpenters’ Joiners’, Cabinetmakers’, and Wheelwrights’, Tools, Engineer’s files, cutlery, iron cramps etc. in addition to the lease.

Full sized example of the Badger Mitre Rebate plane. The Holland skewed Mitre Rebate shown after this one has an identical side escapement to the Badger Mitre Rebate shown here. Basically, it’s a slit with a gentle curve directly above the mouth.

Charles Badger’s Mitre Rebate plane never became very popular, but specialized interest in the usablity of the form inspired later planemakers to create Mitre Rebates. Or more precisely, customers were inspired to have Mitre Rebate planes made, as most of these were commissioned work.

.

This mitre rebate plane was likely made by Charles Badger as well. Rosewood wedge was slotted to fit lugs on the sides.

Mitre Rebate, unmarked, skewed, 8″ x 1 3/4″. Formerly Russell and Ott collections. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, U.K., March 2015.

The next five photos show a small skewed mitre rebate by John Holland, who took over from Badger at 93 York Road in 1871. This mitre rebate example could easily been left over inventory from Badger, that was rebadged by Holland. Here is Cameron Miller’s description of this plane from infill-planes.com

Here’s something you don’t see every day. A custom-made miniature skewed badger mitre plane by John Holland of London. Not only are Holland mitre planes rare, but this one is skewed, small AND badgered!

Measuring only 4-3/8″ long, 1-3/8″ wide and 1-1/4″ high, I would think that this plane would have possibly been made for an instrument maker of some kind. Certainly some of these types of planes, most notably Norris thumb planes, were marketed towards pianoforte case makers and the like. It stands to reason that this mitre plane could’ve been made for a similar purpose.

Rather than a lever cap or bridge to hold down the rosewood wedge, there is a raised rectangular lug on each of the sides of the plane to secure it. This method allows the cutting iron to be withdrawn without fouling or catching on the rest of the plane. In fact, due to the ultra tight mouth, it would be impossible to insert or withdraw the iron anyway by using those two aforementioned methods.

Similarly the escapement on either side is also a simple affair — merely a narrow slot rather than a more open design. All in all it’s a nice little casting.

Due to the short length of the plane, the cutting iron and wedge extend past the heel and are lower in profile than the sides. The shape of the wedge is somewhat flattened in the finial, producing a rather low profile, but the other end does feature a nice cupid’s bow.

The rear face of the front infill has a typical “S” moulding that is often a characteristic of infill mitre planes. The metalwork has light all-over pitting but this is not deep. Supposedly the pictures make it look darker than it is.

At first I assumed (though assumptions can often lead to trouble, granted) that this particular plane may have been one of Holland’s earlier planes rather than a later one. However, the fact that it has the word “MALLEABLE” stamped on the toe would suggest that it is indeed a later plane.

Photos from infill-planes.com:

This New York piano plane was either a one-off, or from a small batch.

This Holtey Mitre Rebate plane was commissioned a good number of years before 2009, and was not a Holtey design. It appears to have an adjustable mouth, and shows some influence of Badger.

A special order Norris Mitre Rebate plane, with two known examples. One served as first prize in The Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers contest of 1941. It has a handle that can swivel as well as pivot, and it also has a captive wedge, and a Norris adjuster.

The ebony Mitre Rebate was a commission, and the Kingwood example was a prototype. Konrad Sauer made an earlier pair of Norris Mitre Rebate planes, in 2008.

From David Stanley Auctions:

Estimate: £10,000 – £20,000 (Fees 22%)

“A unique “Presentation” d/t steel mitre/rebate plane by NORRIS London measuring 13 1/2″ x 2 1/4″ with figured rosewood infill and adjustable handle, previously sold in Tony Murland’s 2006 auction Lot 496 with the following description (which would be difficult to improve on!):

In June 1941 an 18yr old apprentice cabinetmaker Mr L.F.Gillett of Stratford-on-Avon won first prize in the Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers (A.S.W.) annual competition. The prize was a steel mitre plane. The A.S.W. had commissioned the Norris factory to produce a totally unique plane. Norris exceeded themselves in this challenge and the result is an amazing, adjustable handled, rebating mitre plane marked NORRIS London Patent Adjustable.

A silver plaque on the front of the plane is inscribed A.S.W. Apprentice Competition 1st Prize Bro. L.F.Gillett Stratford-on Avon 1941. The plane also exhibits two other features unique to previous Norris planes i.e. the combined handle and wedge is removed by loosening a brass knob, there is then the facility to adjust the handle laterally with a screw on the underside of the wedge. The handle can also be tilted by adjusting a screw at the base of the handle.

A similar Norris plane was sold in our Catalogue No 52 Sept 2008 Lot 1075 for £16,000 These were the only two planes of this type produced by Thomas Norris F.”

The following photos come from David Stanley Auctions, Leicester, U.K.: