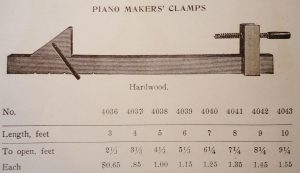

American Felt Co. catalogue, 1914. These clamps have been specifically identified as piano clamps in numerous period publications, including general woodworking publications.

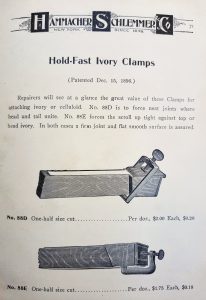

Hammacher Schlemmer ivory clamps, as advertised in the 1913 Hammacher Schlemmer Catalogue. Patented 15 December, 1896.

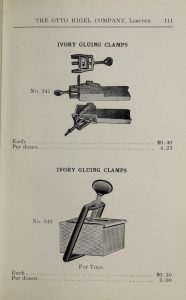

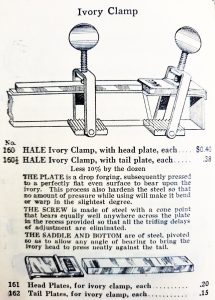

Hale Ivory clamps, 1930 catalogue. This image omits the cone point at the business end of the thumbscrew.

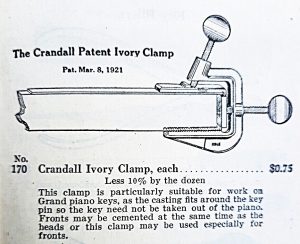

The Crandall Ivory clamp was designed to be used with the key still sitting on the balance rail of the keyframe (see Patent drawing).

The C.H. Lang clamp could also glue up a cracked piano action flange, as shown. Cracked flanges on older pianos was and is a common occurrence. Below Lang’s clamps, are another Hammacher Schlemmer (Erlandsen) piano ivory key clamp. Although the earlier H.S. clamps lacked a bottom plate, like the Hale and Lang ivory clamps, they worked well.

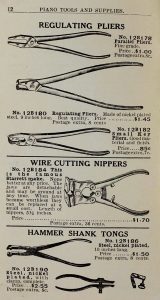

Sears & Roebuck Piano Tools, c. 1900

Sears & Roebuck “Piano Tools & Supplies Catalogue.” Excerpts, circa 1900 to 1910. High quality extension tuning hammer; pin setter and extractor.

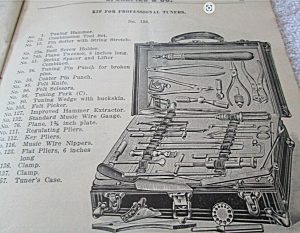

Comprehensive Tuners’ Kit, as offered in the 1914 Shapiro (Chicago) Piano & Instrument Makers’ Catalogue. The tuning hammer is very similar, if not the same as the Sears & Roebuck Extension Tuning Hammer, “Best American Make.” Image from Ebay, June 2023.

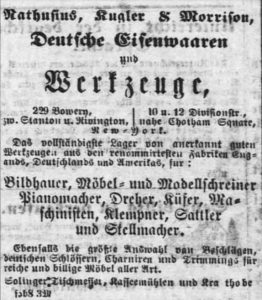

Nathusius, Kugler, & Morrison

Nathusius, Kugler, & Morrison, Pianomakers’ Tools. From Wilson’s 1865 New York City Business Directory.

Nathusius, Kugler, & Morrison were neighbors and competitors of Albert Hammacher in 1865. They specialized in Pianomakers’ Tools, but also carving tools for woodworkers, most notably, the Addis line.

Nathasius, Kugler, & Morrison was established in 1857. From “New York’s Great Industries,” by Richard Edwards published 1884.

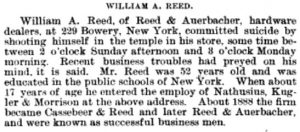

In 1888, Nathasius, Kugler, & Morrison became Cassebeer & Reed, and later, Reed & Auerbacher took over.

Death of William A. Reed, who got his start at Nathusius, Kugler, & Morrison in 1860. From “The Iron Age,” 17 October, 1895.

Irvington Manufacturing Co., Irvington, N.J.

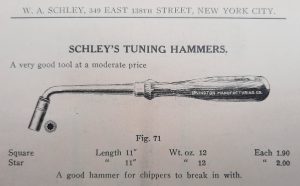

Irvington Mfg. Co. was active from the late 19th century until 1916; they were mostly known for their linesmans’ pliers, which was the tool that they made in the most volume. W.A. Schley Piano Supply Co. at 349 East 138th St. in the Bronx carried the Irvington line.

Irvington Manufacturing Co., Irvington New Jersey gooseneck tuning hammer, c. 1905. Schley Piano Supply.

The W.A. Schley Piano Supply Company was intentionally situated in the South Bronx, at 349 East 138th St. because many piano factories were actively producing nearby.

Multiple Bronx piano factories, including Decker & Son, Ludwig Co., De Rivas, Harris, and the Mansfield Piano Co., Bronx ca. May, 1917. Photo from N.Y. Historical Society.

Despite the fact that these factories were still quite busy in 1917, this image conveys a sense of forlornness. A feeling that would increasingly envelop the Mott Haven neighborhood in the South Bronx throughout the ensuing decades.

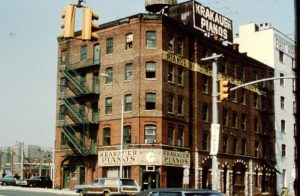

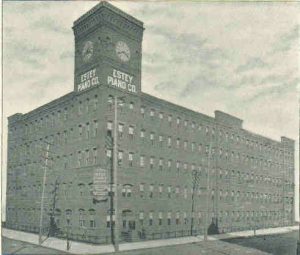

In 1913, essentially the pinnacle of Piano Manufacturing, there were as many as 40 Piano Factories in the South Bronx, and an additional 14 makers of piano components. Here are a number of those Piano Makers, as recorded by Norman E. Michel (1894-1972): Bollerman & Son, 515 East 132nd Ave., Christman & Sons, 869 West 137th.; Francis J. Connor, corner East 134th & 4 East 42nd; Jacob Doll, 916 Southern Blvd.; Hoglund & Co., 515 East 137th; Decker & Son, 916 Southern Blvd.; Estey Piano Co., 278 East 134th St; Krakauer Brothers, corner Cypress Ave, & East 136th; Laffargue Piano Co., 950 East 134th; Henry Lindeman & S.G., 2 West 140th; Ludwig & Co., 968 Southern Blvd., Mathushek (formerly Kroeger) corner East 132nd, & Alexander Ave; Newby & Evans Co., 994 East 136th; Newton Piano Co., 537 East 134th; Regal Piano & Player Co. (also Ricca & Son), 887 Southern Blvd.; Schubert Piano Co., 1 West 139th; Speilman Piano Co., 727 East 147th; Stuvesant Piano Co., 727 East 147th; Winter Piano Co., 220-226 Southern Blvd., c. 1903-1950.

Krakauer would custom duplicate wrestplanks and bridges for piano technicians. From “The Piano Technician,” October, 1961.

When the Krakauer Factory was finally closed in the mid 1970s, at least some of the contents were sold off to be reused. Some of the hard rock maple stock was sold on to John Ford, who then used it on his own projects, as well as for others.

In 1977, Howard K. Graves bought Krakauer, and moved the tooling and remaining stock to Berlin, Ohio, where he opened another piano factory. Three years later, in 1980, Graves sold the Berlin plant to Kimball Piano Corporation; after running the factory as a Division of Kimball, Kimball then closed the Berlin facility in 1985.

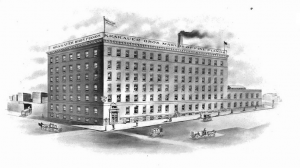

Krakauer Brothers Piano Factory, at the corner of Cypress Ave, and East 136th St. Artistic rendering.

Estey Piano Factory, in Mott Haven. Photo from flickr. Now an official landmark, the “Clocktower Building” houses artists and their studios.

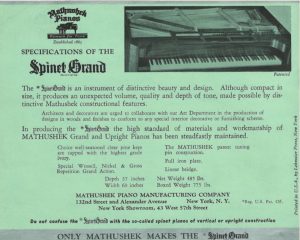

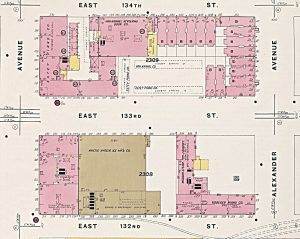

Detail of a 1908 map of the Bronx, showing the Estey Factory, which was built in 1885. The Kroeger Factory became the Mathushek piano factory, at the corner of 132nd St. and Alexander Ave in 1912. Mathushek (under ownership of the Jacob Brothers) continued to make pianos there until 1958, including the innovative Spinet Grand, which was patented in 1935. It was laid out horizontally, not unlike the earlier square grands made in the 19th century.

Estey and Kroeger Piano Factories,The New York Public Library. “Bronx, V. 9, Plate No. 4 [Map bounded by E. 134th St., Alexander Ave., Harlem River, Lincoln Ave.]” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1908.

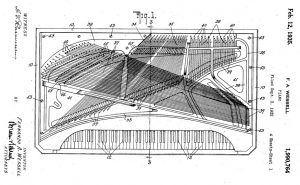

Patent drawing for Mathushek Spinet Grand, by Fernando A. Wessell, 1935.

In addition to having relatively longer strings in a smaller piano, the Mathushek Spinet Grand had a double repetition action, with grand type balanciers on each wippen. Eighteenth and nineteenth century square pianos did not have an action with these features.

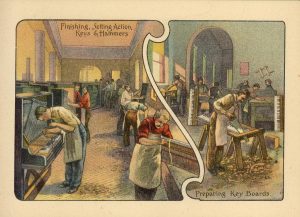

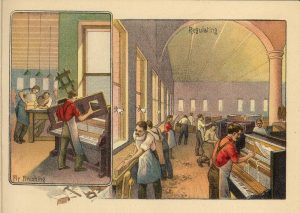

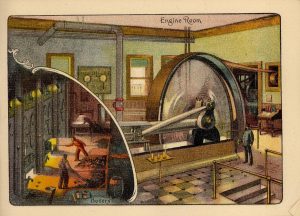

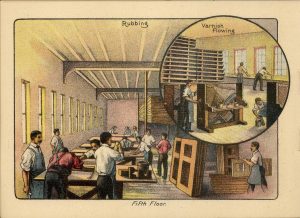

Schubert Piano Company

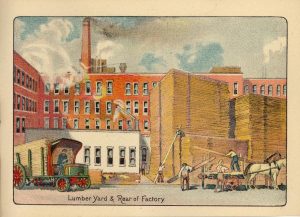

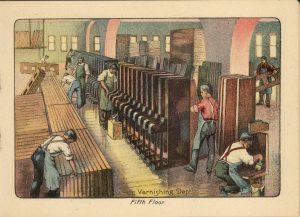

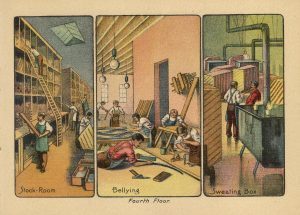

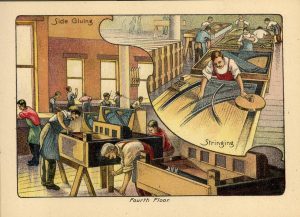

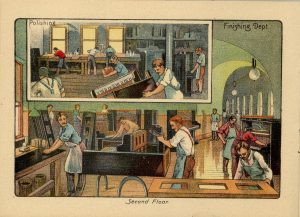

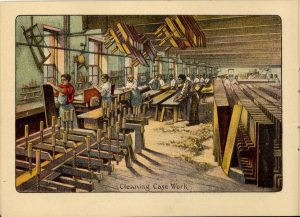

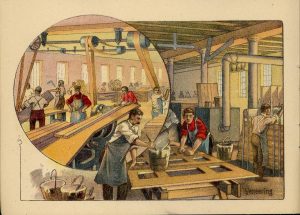

In 1902/03, the Schubert Piano Manufacturing Company built a large 9,000 square foot factory in the Mott Haven District of the Bronx, powered by a 500 horsepower Corliss steam engine. The founder and president Peter Duffy built Schubert Pianos with the original goal of making a high quality instrument at a reasonable price; this business philosophy must have been successful, as the move to 1 West 139th St. was their fourth expansion move in just 22 years. To advertise their new workspace, Schubert published a lavishly illustrated sales brochure, depicting many stages of piano making, albeit in an idealized fashion. A 1903 Schubert catalogue came to market on Ebay in 2023, and that is where these images come from:

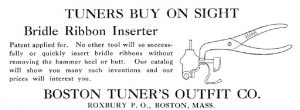

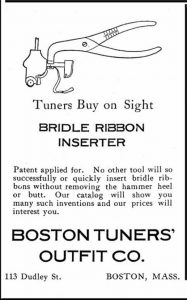

Boston Tuners’ Outfit

Boston Tuners’ Outfit was established by Charles P. Dolan, a piano tuner and dealer, circa 1904, at the corner of Common and Washington Streets, in Boston.

Dolan did more than approximately copy the name Tuners Supply Boston; he made some of his tuning tools with removable tips, very similar to those made by Hale.

This Tuners’ Supply Boston advertisement for “Tuners’…Outfits…” in “Music Trade Review,” during 1905, showed the potential confusion between the two companies.

Charles P. Dolan (1871-1951) did a little of everything related to pianos: he taught piano students, he sold pianos, he tuned pianos, he made piano tools, and he manufactured pianos.

In 1906, Charles P. Dolan was renting commercial space at 837 Washington St., which would become Boston Tuners’ Outfit (if it wasn’t already).

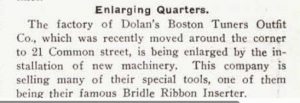

Article on Boston Tuners Outlet move from Washington & Common, to 21 Common St., Boston. “Music Trade Review,” 8 October, 1910.

The Boston Tuners’ Outfit Company had their own in-house tooling, and with their advertising, and intrinsic quality of their line of tools, they succeeded in selling in fairly high volume.

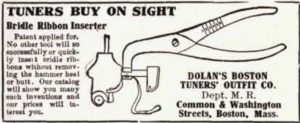

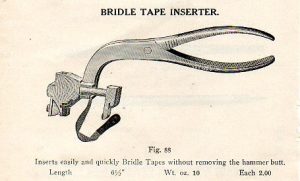

Boston Tuners’ Outfit Bridle Ribbon Inserter, by Charles P. Dolan, but stamped H.S. & Co. N.Y., and shown in the Schley Co. Catalogue c. 1905.

Dolan’s Bridle Ribbon Inserter was introduced as early as 1903, and sold by other suppliers, including Hammacher Schlemmer and Schley. These specialized pliers were likely cast in bronze in-house, and then sent out for nickel plating.

The bridle tape (tack) inserting pliers were the most popular and most produced tool by this company. I never sought out this tool.

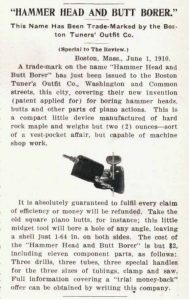

Article on Boston Tuners’ Outfit bridle tape inserter and hammer butt boring jig. “Music Trade Review,” 23 April, 1910.

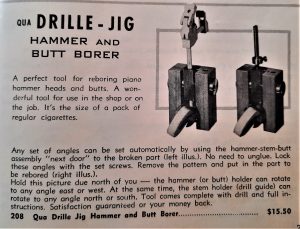

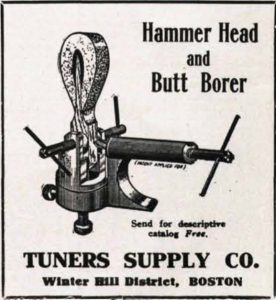

Dolan’s Hammer Boring Jig, in a “Music Trade Review” article written 1 June 1910. Just below this article was a Hale ad for their Hammer Butt Boring Jig.

It was difficult to discern who was first with the Hammer Boring Jig, Hale or Dolan. My guess is Dolan, as Frank Hale in 1910, was just returning from a six-year diversion from Tuners’ Supply Co. in the western U.S., as well as Alaska. All these years later, it makes little difference.

Selection of tools sold by Boston Tuners’ Outlet: upright piano hammer extractor, upright bridal tape inserting pliers (for tacks), piano action hammershank bending pliers (brazed repair opposite side), and “T” hammer, with removable tip, like Hale (Tuners’ Supply) hammers.

With the success of Boston Tuners’ Outfit, Charles P. Dolan got out ahead of his skis by quickly expanding that business and establishing a larger one–Massachusetts Piano Manufacturing Company. It was not long before Dolan relinquished of both of his businesses.

Shirmer bought out Dolan from Massachusetts Piano Manufacturing Co., which produced the Durell Brothers Piano. “Music Trade Review,” 19 January, 1918.

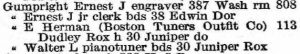

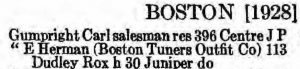

E. Herman Gumpricht (1865-1933) English: Gumpright, a tuner and piano-factory technician, bought Boston Tuners’ Outfit circa 1913, and moved the business to 113 Dudley Street, Roxbury in 1915.

Boston Tuners’ Outlet, advertisement in “Tuners’ Magazine,” July, 1913. Dolan not mentioned, and shop no longer at 21 Common St.

Same Boston Tuners’ Outfit advertisement by Gumpricht, after move to 113 Dudley Street, Roxbury, Boston, Mass. “Tuners’ Magazine,” December, 1916.

Emmanuel Hermann Gumpricht worked in the piano industry his entire life: as a piano factory technician (late 19th c.), as a piano factory tuner (early 20th c.), as an owner/proprietor of Boston Tuners’ Outfit (1913-1928), then as a private piano tuner (1929-1933).

Herman Gumpright was a private piano tuner living at 30 Juniper St.,Roxbury, in the 1930 U.S. Census.

Final year for Gumpright (1928) and Boston Tuners Outfit at 113 Dudley St., Roxbury, in the Boston City Directory.

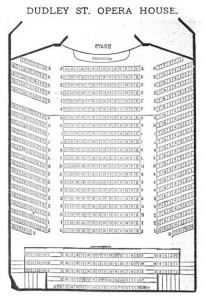

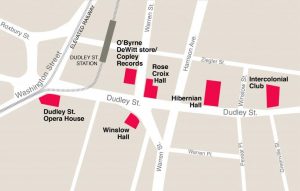

113 Dudley Street in Roxbury was the location of Dudley Street Opera House, which was established in 1879, and still active as a music venue as late as 1961. Dudley Street was very popular with music lovers.

Dudley Street Opera House, 111-117 Dudley St., Roxbury, in the 19th Century. E. Herman Gumpricht would have rented one of the storefronts on the ground floor. Photo from Wikipedia Commons.

Remarkably, the Dudley Street Opera House was still in operation in 1961-its final year. 1961 Boston City Trade Directory.

Intersection of Dudley Street and Warren Street (one block east of Dudley Street Opera House, looking west, showing elevated railway), circa 1905. Photo from historicnewengland.org

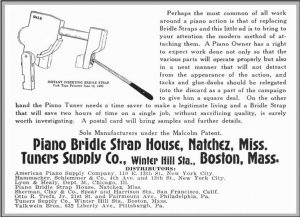

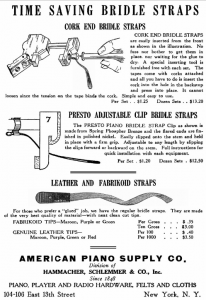

Malcolm’s Cork Bridle Strap

Just under twenty years after Dolan introduced his bridle ribbon inserter (and several other piano tool makers had their own bridle tack inserters on the market), Thomas Jefferson Malcolm patented his cork bridle strap. Malcolm, originally from Okmulgee, Oklahoma, established a bridle strap production shop in Natchez Mississippi. The cork and clip bridle straps dominated the market for this common job in a few short years. Hale Tuners’ Supply, became the second manufacturer of the cork bridle strap, as well as a distributor..

Cork and phosphor bronze clip bridle tapes as sold by Hammacher Schlemmer. From “The Tuners’ Journal,” March, 1930.

In 1928, Malcolm patented another cork bridle strap glued on the outside of the cork, which is the version we see today.

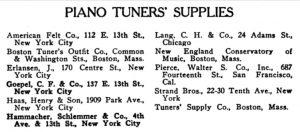

Other Minor Piano Suppliers

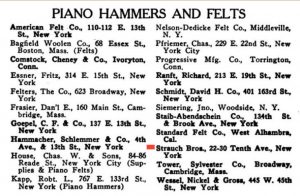

“International Directory of Music Industries, Embracing Classified Lists of Manufacturers,” by Abbott & Daniel, Presto Publishing 1911.

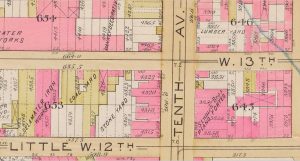

This 1911 list of piano suppliers includes three that I have not covered so far in this website. After frustration at not finding anything for “Strand Brothers” (sic) piano suppliers, I looked up the location on a period map. This cleared matters up immediately.

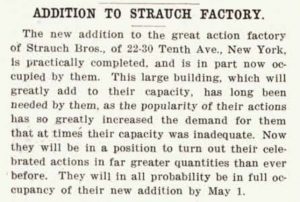

Strauch Brothers provided hammers and action parts for piano technicians and piano makers, but they were not comprehensive suppliers for tuners.

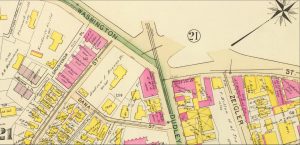

Strauch Brothers Action Manufacturers 22-30 Tenth Avenue, New York, N.Y. Excerpt from Bromley Map of Manhattan, plate no. 10. Published 1891.

Hammer Suppliers, including Strauch Brothers, in “International Directory of Music Industry…” by Abbott & Daniel Presto Publishing, 1911.

Strauch Brothers Piano Action Makers, advertisement in “Watson’s American Weekly Art Journal,” November 21, 1891.

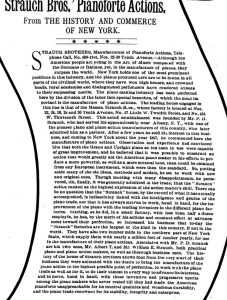

Strauch Brothers Tribute, excerpt from “History and Commerce of New York,” published in “Watson’s American Weekly Art Journal,” 21 November, 1891.

Peter D. Strauch (1836 Germany-1924 Tuckahoe, N.Y.) founded Strauch Brothers Piano Action Manufactory in 1867; the Strauch Brothers were his sons Albert T. and William E. 1870 N.Y.C. Directory

Peter D. Strauch and his sons made a concerted effort to reach out to, and work with, piano tuners. His company would rebuild actions of various makes as well as sell action parts, hammers, and related supplies to the piano servicing trade.

Before Walter S. Pierce was running his own factory, he was a clerk for Andrew Kohler, who served as the president of Kohler & Chase Piano (then dealers only) from 1850 to 1885. San Francisco City Directory, 1862.

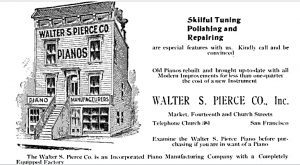

Walter S. Pierce is covered by his namesake, Bob Pierce, in their Piano Atlas, and for the Pierce entry, they show a photo of a relatively modest looking storefront no more than 40 feet wide, with signs for a “Piano Factory;” also piano sales, piano tuning, repairing, and varnishing, as well as Columbia Recordings.

Here is the Pierce Atlas entry:

“The Pierce Piano Manufactory was established in 1863 by Walter S. Pierce and W.E. Pierce at 14th and Market in San Francisco, CA, then moved to Market St. opposite Second St., in 1866. Around 1882, the firm moved to 4th and Bryant St. (burned in 1884), then moved to 689 14th St.; 1885 at Montgomery and Sutter St., San Francisco, CA., The company incorporated in 1893. Also manufactured the California Piano, Grosjean, and Creighton. [Walter S. Pierce] died in 1930 and the business closed.”

Chronology for the Pierce entry shown above, was corrected in several places, but words were not changed.

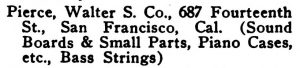

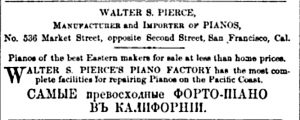

Walter S. Pierce Piano Manufacturer, supplying Soundboards, Cases, and Piano Backs to the Piano Industry, and custom Bass Strings to Tuners. From “International Directory of Music Industries,” by Abbott & Daniel, Presto Publications, 1911.

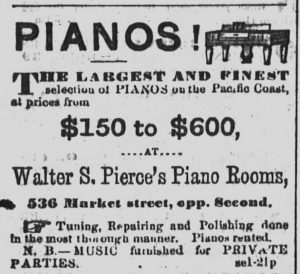

Pierce advertisement from “San Francisco Chronicle,” San Francisco, California, Saturday, 20 Oct 1866, page 1.

Walter S. Pierce advertisement in the “Alaska Herald” (book) published 1868. Secretary of State William H. Seward had just arranged the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867.

Fox’s Music Trade Directory of U.S., p. 38; published 1928:

“WALTER S. PIERCE COMPANY . Ca- Offices and Factory – 689 14th St. , San Francisco , Cal . Established – 1863 . Capital Stock- $ 30,000 . Walter S. Pierce , proprietor and superintendent.”

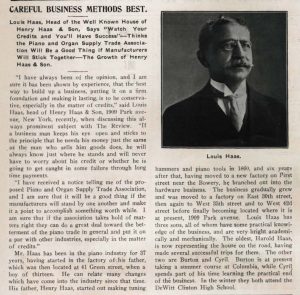

Of these three minor suppliers, Henry Haas & Son was the only one offering a full line of piano tools and supplies for piano tuner-technicians, but remarkably, I have not found any Haas piano tools in 45 years of collecting. Perhaps they did not stamp their tools and supplies.

After reviewing the advertisement ephemera produced by Henry Haas & Son, Inc., it became more apparent why I have not found marked piano tools sold by Haas. Even though Henry Haas started out in the piano business in 1860, making piano tuning hammers and specialized piano tools, he soon branched out into a wider range of supplies, eventually specializing in piano hardware. Nowhere did I find a Haas advertisement for piano tools.

Otto Marwedel Hardware Supply, San Francisco, CA, 1862. From Online Archive of California (OAC), Business Archive Collection.

Marwedel Machinists’ Tools & Hardware, San Francisco

There are conflicting sources for the founding date of Marwedel’s Tool and Hardware business. One account gave 1846 as the founding year, and I also found an Otto Marwedel running a hardware supply business in San Francisco for 1862 (Marwedel is not a common surname). The advertising literature for C.F. Marwedel, and later C.W. Marwedel gave 1872 as the founding year. After issuing many large tool catalogues over the years, C.W. Marwedel sold out to the Garrett Corporation of Los Angeles in 1955, and continued to operate into the 1960s; Marwedel’s 1953 Machinists’ and Industrial Tool Catalogue had 1404 pages!

Here is the account from Barry Cassidy Rare Books:

“C. W. Marwedel was founded in 1846 [probably 1872] by its namesake. Marwedel had immigrated to San Francisco, California in 1856 and opened his shop there which originally specialized in optical and electrical devices. Over the years, Marwedel expanded his stock to carry a wider range of machine tools and supplies. In 1928 or 1929, Marwedel [added a business location in] Oakland. Marwedel made it through the Great Depression and World War II but eventually sold his store to Garrett Supply in Los Angeles in 1955.”

“Electrical Devices”: here is where the chronology of this account becomes difficult. Thomas Edison invented his electric light bulb in 1879, and electrical fixtures were introduced towards the end of the 19th century.

In the early 1920s, C. W. Marwedel branched out into piano tools and supplies; it looked like they carried the Hale line, and possibly others. Having the largest piano supply stock west of Chicago in the early 1920s was not a high bar. And I did not find evidence of Marwedel remaining in the piano supply business for more than a few short years during the 1920s.

Marwedel Piano tools and supplies, advertisement in the “The Tuners’ Journal,” September, 1921. Note the milling cutter.

Marwedel Piano tools and supplies, advertisement in “The Tuners’ Journal,” January, 1922. Hale Extension Hammer.

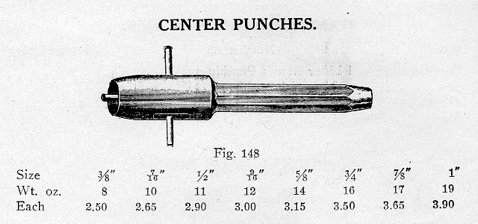

Archimedean drills

Archimedean drills found within a set of British piano tools. Not to be confused with bow drills, they produce a reciprocating or continuous motion by sliding the middle handpiece up and down. Archimedes, an ancient Greek scientist, invented a screw which pulls water from a lower body to a higher plane; the drill was actually a 19th century development.

- The larger drill, made by Hobbies, with rotating counterweights, has a clutch within the sliding center handle which disengages when it is lifted: this creates a continuous motion.

- The smaller one does not have this feature, the drilling is reciprocal as in a bow drill. Small Archimedean drills are still frequently used by jewelers and small craft workers, where deliberate and precise drilling is controlled by hand.

Archimedean drills found within a set of British piano tools.

Demand is such that several sources provide new Archimedean drills.

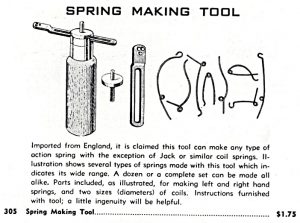

Piano Action Spring Making Tools

Antique rosewood brass and steel piano action spring making tool. This tool is no longer available in the U.S., but can be found from Fletcher & Newman in the U.K. and Renner in Germany. It looks like there is a reference to Germany faintly inscribed on this one:

German piano spring making tool, c. 1920.

Renner catalog.

Regulating Rack or Jig

Trefz and Co., Philadelphia, c. early postwar. Regulating rack.

Trefz and Co., Philadelphia, c. early postwar. Regulating rack, used to recreate hammer escapement and drop positions with the action out of the piano. This example was made with bird’s-eye maple, which I’ve never seen in more recent examples of this tool.

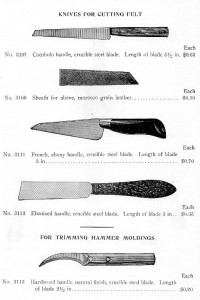

Some Piano Edgetools

Soundboard shimming tool, very long, with a really narrow blade.

Blade of Shimming tool, close up.

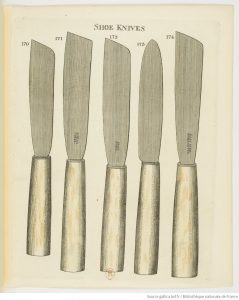

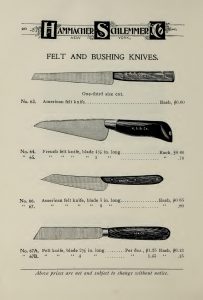

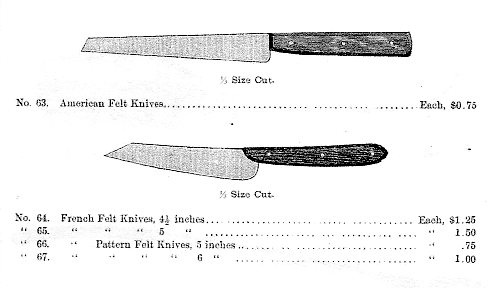

Typical felt knives. H. S. and Co. 1885.

Felt knives were originally shoemakers’ knives–for cutting leather–with a history going back several hundred years. Smith’s Key was one of the earliest tool catalogues published.

Two French felt and leather cutting knives by Blanchard, Paris; English knife made by J. Tyzack of Sheffield

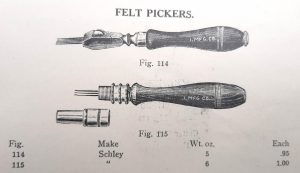

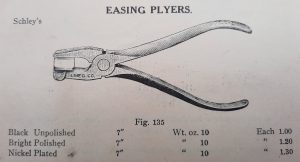

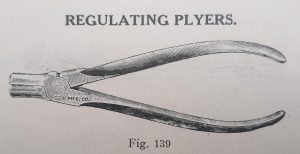

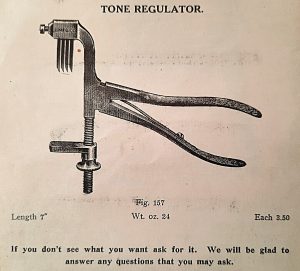

Schley 1905.

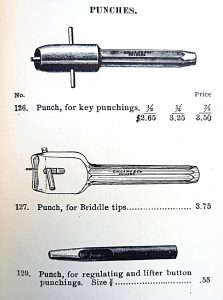

Punch for making front rail punchings.

Damper Felt Guillotine

Damper felt guillotine, from the Weber Piano Company.

Damper felt guillotine, from the Weber Piano Company, founded by Albert Weber, in New York, in 1852. At 20 inches long, and 10 inches high, this is a serious felt cutter, larger and heavier than any of the guillotines that I’ve seen produced for the piano service trade. It still cuts very well, without the side effects of repeated sharp impacts on my palms that I’ve received from using other guillotines with a vertical plunger.

G.F. Baker made their proprietary stamp on an ivory keytop for a piano keyboard, and this particular guillotine was primarily intended for cutting keyboard backrail cloth, stringing felt and cloth, and secondarily for cutting damper felt strips into blocks for gluing onto damper heads. The blade moves on a pronounced arc. Photos from Ebay U.K.

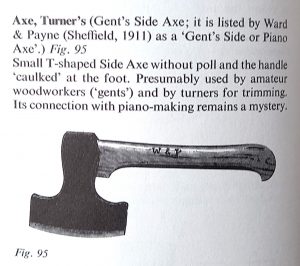

Pianomakers’ Axe (!)

During the Victorian era, turned legs for ornate piano cases were very much in vogue. In order to save wear and tear on the edges of turners’ chisels (and stress on their wrists), this axe would be used to knock the corners off the hardwood blanks before mounting in the lathe. How would you use this axe?

Pianomakers’/Turners’ axe. Photo by Bill Carter.

Alnutt’s Bass String Retoner

Bass string retoner.

Close-up of the manufacturer’s imprint.

Alnutt’s Bass String Retoner, as described in the April 12, 1919 (p. 41) edition of the “The Music Trades.”

This “bass string retoner” was designed to improve tone quality on bass strings by compressing the copper windings against the steel core instead of twisting them! An invention by Lawrence Alnutt, intended for dealers and others in the piano business. I had marginal success, at best, when experimenting with this tool. This invention went nowhere, and therefore is quite rare; beyond the novelty and curiosity factor, it has received little attention, perhaps deservedly so:

Hand Vices

Early European hand/pin vise.

Hand vise, useful for holding very small parts in the field. This example is very similar to the hand vise depicted in “L’Art De Accorder,” written by Montal in 1836, shown on the “Tuning Hammers” page. This was probably made in England.

Hoover Action Screw Holder

Hoover patent action screw holder.

Patent for this screw holder. Franklin Hoover authored three piano tool patents in this website: this screw holder, a hammer extracting pliers, and a voicing pliers, similar to the later Hale voicing pliers.

Excerpt from text of patent:

Feeler for checking the glue joints of soundboard ribs (and other things). Spruce handle.

Piano hammer clamp.

Thayer backcheck tool.

Action Center Tools

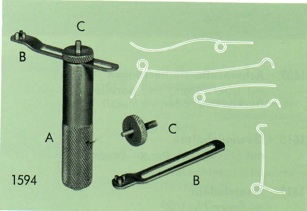

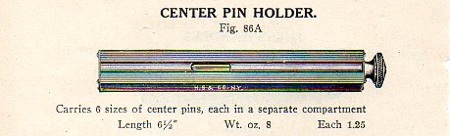

Center pin tools: broach holder/pin vise, pin punch, reamers and burnishers, center pin holders. Rosewood was no longer used for center pin holders after the WWI era.

Another version of a center pin holder, c. 1905.

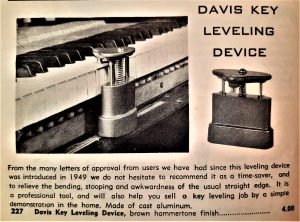

Various products offered in the Hale 1957 Catalogue:

The Hammer and Butt Boring Jig was not a new idea; this version was advertised by Hale in “The Music Trade Review,” in 1911.

Krylon Spray Paint Cans. The source of many repainted plates from the 1950s–with strings attached. 1957 Hale Catalogue.

When spray paint cans first became available, they were promoted as a kind of “miracle spray.” You are looking at a cartoon of a man spraying his workshop tools with a clear coat of acrylic finish. This practice was taken up by some collectors from the early 1950s to the early 1970s. While the clear coat could easily be removed from bare metal surfaces, it was much more difficult to address on wood surfaces, such as those on valuable antique furniture with shellac finishes, etc., and on the wooden components of rare tools and artifacts worth serious money.

Hale advertisement for sets of piano hammers, grand and upright. From “The Tuners’ Journal,” October, 1952.

For many years, I did not think much of the quality of the hammerfelt that Hale used in their Somerville, MA facility. I thought it was generally too soft, resulting in a dull sound making for great difficulty in projecting a melodic line. And I heard similar complaints from other piano technicians in Boston, circa late 1970s, early 1980s.

When I introduced this website back in the aughts, I was contacted by a professional tympanist for a major symphony orchestra. He wanted to know if I had a stash of that “wonderful Tuners Supply Hammer felt” which he had sourced from Hale, until they closed down in the 1990s. At that late date, Tuners Supply Co. had been outsourcing all their products for many years, so the original maker has been lost to time. He told me that the Hale felt created a superb dark tone that he had not been successful in achieving with other felt products. I did not stash any Hale piano felt, but it did give me a new outllook on Hale’s Hammer felt (and other things).

“Around 1825, Berlioz’s favorite timpanist, Charies Poussard began using sponge-headed mallets to achieve a more blended sound especially for rolls. These baguettes d’éponges were soon popularized by the Leipzig timpanist Ernst Pfundt as schwammschlägel. In 1830 piano felt started to be used to cover timpani mallets. Thick blocks of piano felt could be sliced into different thickness and the timpanist could make numerous sticks of different hardness creating new sound palette.”31

–Richard K. Jones

Seven Tuners’ Supply Co. unmarked vintage hammer presses have been stored for years, and are now available for sale, and there are two models included: one for the underfelt, and a second for the top layer of hammerfelt. The seller wishes to see the hammer presses go to an individual who intends to use them to produce piano hammers, rather than to a museum or some other inactive capacity. Also, the seller prefers to sell all of the hammer presses together, rather than part out the collection.

Serious inquiries may contact me, and I will forward contact information to the seller.

Within the piano servicing space, there is, and has been, a great deal of attention and focus directed towards the ‘ideal piano hammer,’ and there may be some market for another domestic piano hammer maker, as much of the aftermarket hammer business is dominated by German and Japanese brands.

The Era of Chemicals to Treat Pianos

One of the trends after WWII was the increasing focus on various chemical products to solve problems. Today, we still use chemical solutions to address issues with pianos, but in general, the products have improved over the years.

Hale Tuners’ Supply advertisement for various chemical solutions to solve problems. “The Tuners’ Journal,” October, 1951.

Bowen Piano Carrier:

1919: Model “T” Ford; 1928: Model “A” Ford.

Miscellaneous (very)

Nick says, “Soundboards are like women.” A hollow-faced moulding plane sat on the soundboard in the foreground: this plane would create the rounded surfaces on the top of the soundboard ribs. Go-bars for gluing ribs to soundboard panel in background. From “The Tuners’ Journal,” June, 1926.

Aluminum piano plates: not a great idea. Aluminum expands and contracts greatly with temperature changes and deflects under stress loads. From “The Piano Technician,” January, 1949.

Advertisement for the Stroboconn which was introduced in 1936. From “The Piano Technician,” October, 1948.

When I moved from New York City to the San Francisco Peninsula in 1986, I met a couple older technicians on the verge of retirement, who were weaned on the Stroboconn in the late 1940s, or Conn Strobotuner in the 1950s, and never learned aural tuning at all. Coming from the East Coast where a higher percentage of tuners at that time were tuning by ear, this came as somewhat of a surprise to me.

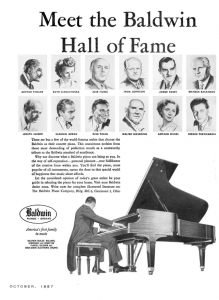

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, Baldwin Piano Company of Cincinnati, Ohio seemed like an infallible institution that would always be with us. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, a Baldwin SD-10 Concert Grand resided at Boston Symphony Hall along with Steinway. Today, it is hard to imagine a time when Baldwin pianos had such an impressive artist roster. Of the artists shown in this Baldwin advertisement, Arthur Fieldler, Jorge Bolet, and Claudio Arrau moved me deeply with their performances. All of these performing artists have passed on, with the exception of Ruth Slenczynska, who is 99 years old in 2024.

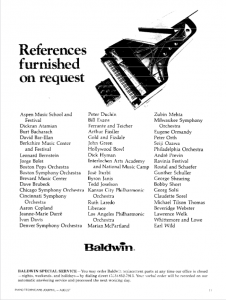

In 1979, Baldwin advertised a larger list of concert artists and symphony orchestras, including: Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, Denver Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Milwaukee Symphony, and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Part of an Organ Tuner’s Outfit, with many cones and two Reynolds tuning hammers. Sold by David Stanley Auctions, March 2013.

David Stanley Auctions, lot 302 description:

“A very comprehensive kit of organ tuners tools entered into this auction by a retired Cumbrian organ tuner, the large hardwood coning tool (tuning horn) was passed down from his great, great grandfather through the family who followed the trade. The kit includes 4 double coning tools (the longest made specially at RAF Workshops in Gibraltar so he could tune the pipe organs in the Cathedral and the Governors Chapel) a set of 4 boxed John Walker tuning forks with named pitches etc all as illustrated and including a list of all the tools with a description of their function, eg. a reed puller for extracting “free” reeds from American organs and a wooden spill plane to make spills used for lighting candles, pipes, cigarettes etc.”

Planes For Metal Organ Pipes

From David Stanley auctions, Sept., 2014.

A very rare and early organ pipe makers combination voicing plane, a steel soled brass mitre plane with rosewood infill and wedge 10″ x 2 1/4″ used for thinning the surface of the tin or lead alloy sheets [spotted metal] used for the metal organ pipes, the iron can be changed to the vertical position and becomes the thicknessing plane (see SAL p287) when vertical the iron is held firm by the front infill being tightened with a brass screw, chip to wedge, most unusual.

‘Smiths’ organ pipe plane. Photos from Ebay c. 2015:

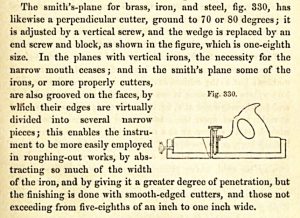

Smiths’ Plane for metalworking, as described by Charles Holtzapffel in “Turning and Mechanical Manipulation,” published in London, 1850.

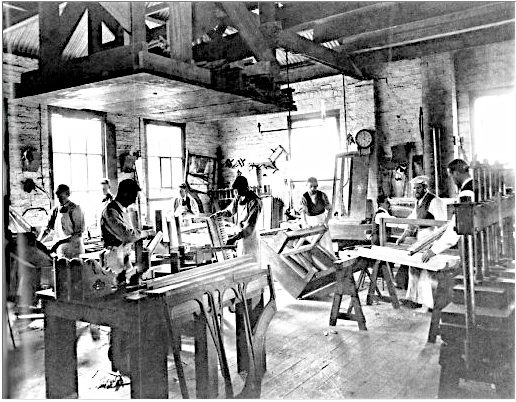

Holtzapffel Metal planes, Mitre, Smoother, Rebate, and Jack; Silcock’s Patent Plane; Smiths’ Plane for metalwork. Holtzapffel 1849 Price List

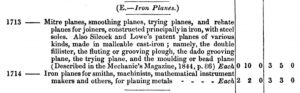

Howell Piano Factory, New Zealand, 1898. Here is a typical early photographic example of piano factory workers, at their work stations. While the products worked on are relatively apparent, its hard to ascertain precisely what the employees were actually doing. Otago Daily Times, April 28, 2012 –Geoff Adams.

Tool cases:

Tuner’s antique satchel and tool roll, made of Moroccan leather.

“Gnome Brand” Tuners’ case. This was included in the 1925 H. S. catalogue, and when I started working on pianos at the end of the 1970s, this case was still available from Tuners Supply (Hale).

“The piano doctor.” My business partner, now deceased, used this to carry his tools. I tried it, but was underwhelmed by the lack of accessibility through the top opening and the lack of space. It was another example of form over function. Besides, I wouldn’t want to invite anyone to make more “piano doctor” jokes.

January 1947 advertisement by Hammacher Schlemmer Piano Supplies Division, for the Gnome piano tuners’ toolcase.

After WWII, Hammacher Schlemmer had really “had it” with the piano supply business; their upscale exotic novelty line, introduced in the 1920s, had really taken off, and their piano supply sales had stagnated, with the depression of the 1930s, and the overwhelming distraction of the war in the 1940s. It did not help matters that H.S. & Co. did little to sustain the piano supplies division, let alone innovate in later years. This 1947 advertisement for the “Gnome” piano tuners’ tool case was one of the very few advertisements from the Hammacher Schlemmer Piano Supplies division after the war.

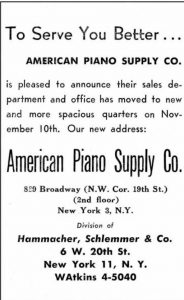

Surprisingly, Hammacher Schlemmer relocated its American Piano Supply Division just months before the Schadler buyout. From “The Piano Technician,” January, 1954.

This move, from 229 4th Ave., to 829 Broadway was likely done in an effort to make the H.S. American Piano Supply Division more attractive to (expensive for) buyers.

H.S. & Co. N.Y. was essentially waiting for 10 years, for the Schadler family to inject new life into the American Piano Supply.

I acquired this Gerstner walnut tool chest new in the late 1970s. Originally, all of the green material was felt. Coming from the piano industry, which generally utilizes woven cloth for bearing surfaces, rather than the pressed fibers of felt, when the the small work surface wore out, I replaced it with green stringing cloth. This material came from from Johannes Warger, a San Francisco based Dutch American piano technician who passed away in 1986.

The thick green cloth was installed with hide glue, so that in the future, it can be replaced again by steaming out the existing material with a minimum amount of effort.