(Tuners Supply Company)

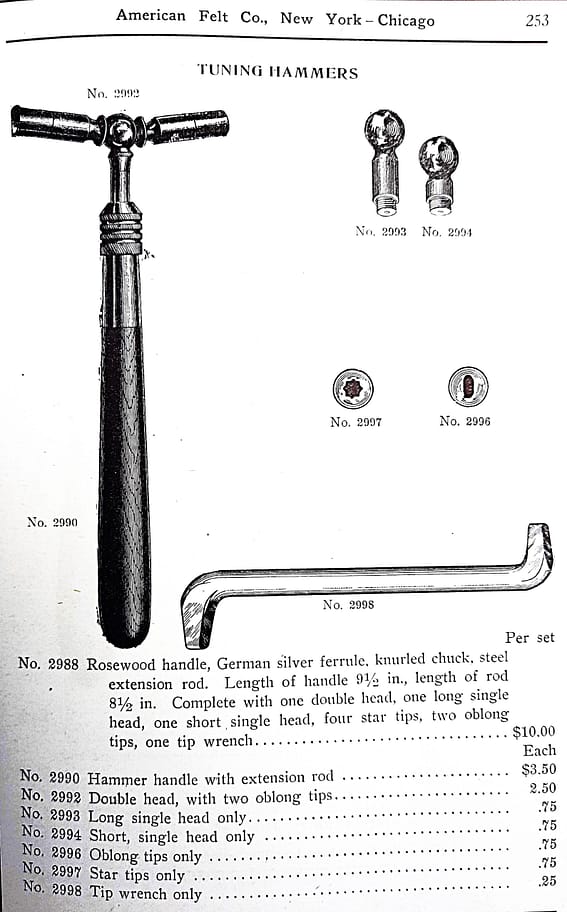

TUNING HAMMERS

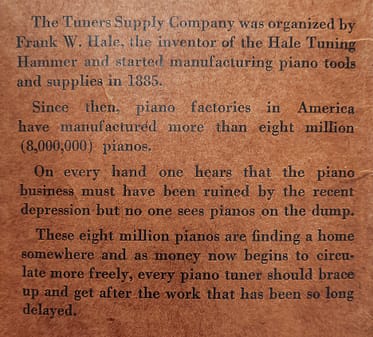

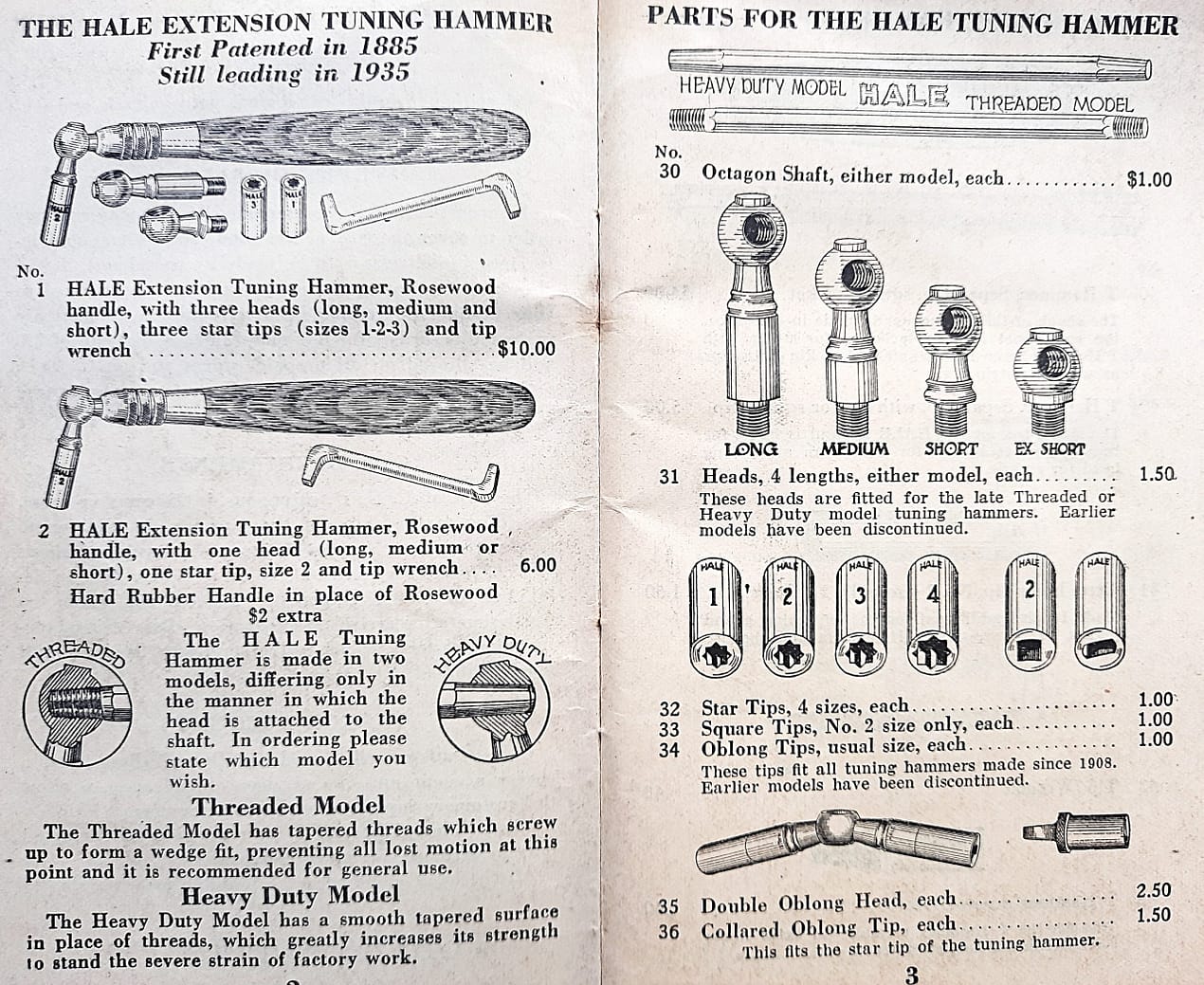

This page is devoted to Hale hammers; other various Hale piano tools are shown throughout this ‘site. The Hale tuning hammer was one of the best on the market, from its invention in 1885, but there was competition from Erlandsen, whose tool production had already been established since 1863, and from Hammacher Schlemmer, whose hammers were mostly made by Erlandsen. After WWI, Hale hammers became more of the leading choice for piano technicians and tuners. Market share increased after 1929, as the industry shrunk, Julius Erlandsen downsized his business during the 1930s, and Hammacher Schlemmer moved to midtown Manhattan in the 1920s, and became more interested in marketing the high-end novelty items that they are known for today.

Hale hammers went through a number of permutations during their production, which lasted well over a century. This review of the Hale hammers does not purport to be a type study along the lines of the many Stanley tool studies (where there are all too often many examples of exceptions to the various categories), but more of a general review of the the history and development of the Hale tuning hammer. In compiling information for this, I have used U.S. patents, advertisements, technical circulars, catalogue excerpts, and the actual tools. As far as I know, there has not been any previous outline or retrospective done on this very specialized subject, so I’ve put it together from scratch, relying on what information that I have been able to cull. This also applies to my page on the history and development of the Erlandsen tuning hammer.

USING HALE HAMMERS

Earlier Hale hammers (1885-1913) with German silver hardware–while some of the most beautiful tools ever made–had an extension feature that was not as robust as the later hammers. Hale hammers with the pre-1908 tuning tips were more suited for tuning older American pianos in original condition up to the early 1960s, and for many European pianos.

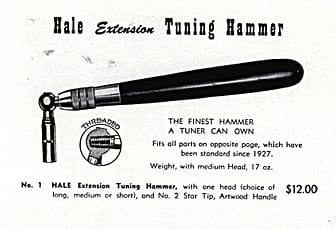

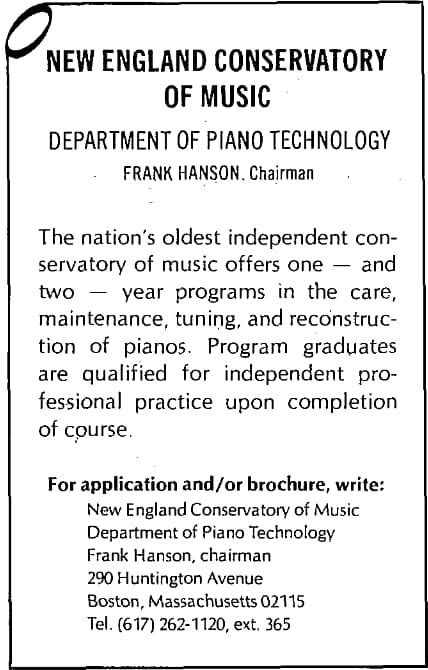

Good used Hale hammers made after 1914, however, are still in demand from some tuner technicians who appreciate traditional methods and vintage tools that are still usable in a practical sense. Post-1908 tuning tips are interchangeable with more current APSCO, Schaff, and Watanabe tips, and the 1/8″ tapered pipe thread (introduced c. 1925) for the head and shaft is still used on Schaff and other modern hammers. A full range of hammer head lengths and shaft boring angles (from 5 to 20 degrees) were available, making the Hale hammer quite versatile for a wide range of tuner preferences, including an extra long head and tip for stringing, which allowed for extra clearance over the cabinet while pulling up the string tension. The steel compression nut (introduced c. 1916) locked down the round shaft (c. 1942–1990s) securely, but the octagonal shaft (c. 1909-1942) was even more solid with no rotational movement under stress. Later Hale hammers with grey Polypenco nylon handles (c. 1956 to the 1990s) were practically indestructible but rather ugly.

A major advantage of Hale hammers was the ability to fit various tuning tips with larger sizes for tuning pin sizes 3.0 to 6.0 used for restringing, and a smaller size for European and late 19th century pianos. Changing the tuning pin tip had to be done in the shop, though, because removing the tip from the head required a tip wrench clamped in a bench vise, and some force applied. For practical purposes in the field, separate heads would be carried, or even a second hammer with the alternative size tip socket.

Post-WWI Hale hammers were different from all of the other types of antique hammers because they could be used to tackle just about any tuning or stringing scenario, while most other antique tuning hammers were good for performing a more specialized range of tasks. The structural integrity of the adjustable extension handle combined with the almost unlimited choices of heads and tips enabled the tuner to use it in almost any situation, from serious concert tuning and factory stringing, to quick and dirty remedial tuning on a spinet gone unserviced for 40 years.

SOME HALE HISTORY

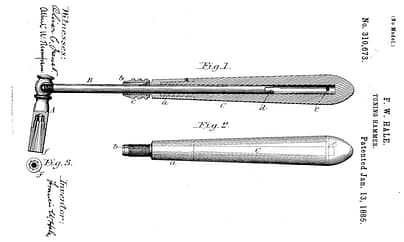

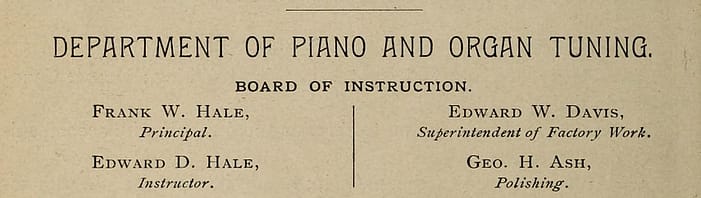

Francis Wayland Hale (1853–1933) was a Tuning Instructor at The New England Conservatory of Music, as well as a student finishing his studies for the Bachelor of Music (1884) at Boston University when he submitted his patent application on February 26, 1884, for this tuning hammer.

His tuning hammer invention featured a collet tightened by an adjustable nut, which secured the variable extension lengths of the shaft. I believe that he was influenced/inspired by the adjustable tool handles which had become commonplace by the 1870s (see “Combination Handles” page). In the example shown below, there are several shallow holes drilled along the shaft to provide places for an auxiliary set screw which is located toward the back of the ferrule. This set screw is seen in the left hand side of figure 1, item “a”, of the patent illustration above. On the opposite end of the shaft is a fork-shaped clutch which, when the extension is fully retracted, provides a very secure means of unscrewing/removing tuning heads that can be very tight. This is shown as “D.” in the patent illustration. Item “e” is a brass pin drilled through the back part of the handle and through the internal hardware, to insure that it remains secure in the handle and will not work loose or rotate. The head, “A,” is made of regular steel near the shaft,, and hardened steel near the socket for the separate tip, appropriate for securely screwing the tip into the hammer head socket. This separate tip, “f,” with male threads, is made of soft steel, and then hardened steel at the tuning pin socket, to withstand the hard usage and wear of turning tuning pins.

The principal benefit of this arrangement is that the tuner had available a choice of socket sizes for the variety of pin sizes and shapes found in pianos in the late 19th century. This tuning hammer model essentially marked the start of the (Hale) Tuners Supply Company.

Hale hammer, early pre-patent, circa 1880-1884. This hammer head has a removable tip, with the male threads. The ferrule and adjustable nut are made of nickel plated brass.

Another early, pre-patent Hale Extension Tuning Hammer. “Pat. Apl.For” c 1880-1882. Note extra short very early Hale tip.

Another view, showing the set screw and the drilled holes for the screw along the length of the shaft.

Pre-patent Hale Extension Tuning Hammer. “Pat. Apl. For.” Close up of hardware with single set screw, rather than collet.

Early Hale hammer, shown below, c. 1885-1895, with head very close in appearance to that shown in the 1885 patent, the date of which is inscribed on the matching original double oblong head for it. This hammer has a ferrule, collet, and adjustment nut, all made from German silver, and Hale used German silver for this hardware until early in the production run of the “Cup-Joint” model, c. 1916 or so. German silver was used in many higher end tools in the second half of the 19th century, as it was showy, relatively easy to work, resisted corrosion, had low friction, and was somewhat more durable than brass. It had many uses, such as for piano center pins, keys for woodwind instruments, flatware, and jewelry that Indians made on the Great Plains. Manufacturers of this alloy, 60% copper, 20% nickel, and 20% zinc (with varying combinations), would compete to achieve the most silver-like appearance.

The set/guide screw, was moved to the front of the ferrule, near the adjustment nut, and the shaft had a channel along its length, rather than divots for the set screw, allowing an unlimited number of length settings. And the shaft extension now had a flare, which provided a friction locking/mating surface for the head. In other respects, the 1885 Hale tuning hammer remained pretty much the same as before.

Hale hammer with 1885 patent, and similar hammer a few years later, with different knurling on adjustment nut, shorter head, and slightly longer tuning tip. While old Hale hammers enter the market occasionally, it’s more of a challenge to find examples in fine condition.

HALE NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY AND FAUST

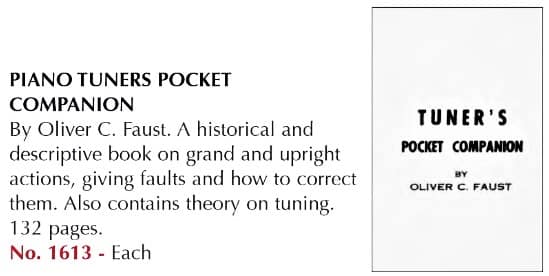

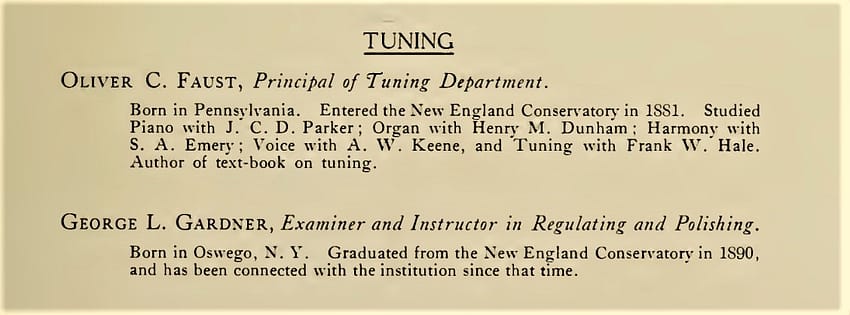

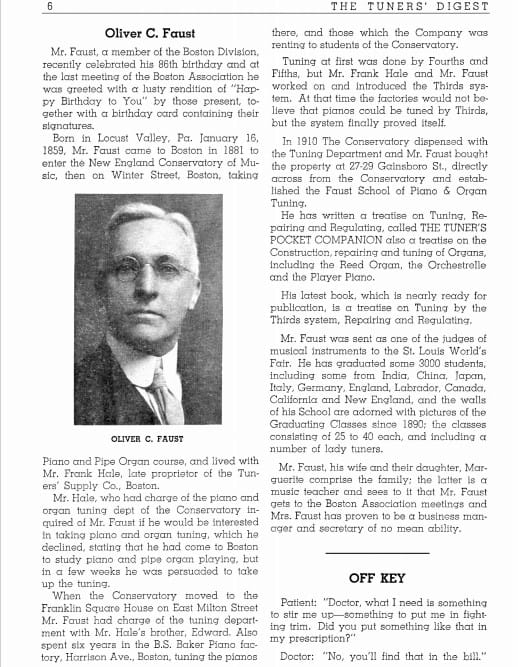

“Tuners’ Pocket Companion,” by Oliver C. Faust (1902), amazingly, still available for sale in current Schaff Piano Supply Catalogue.Faust’s Tuner’s Pocket Companion remained in print for the entire duration of the Hale/ Tuners Supply’s tenure in business (I bought my copy in 1978). It is still available today from Schaff Piano Supply, who bought out the Hale name, c. 2000.

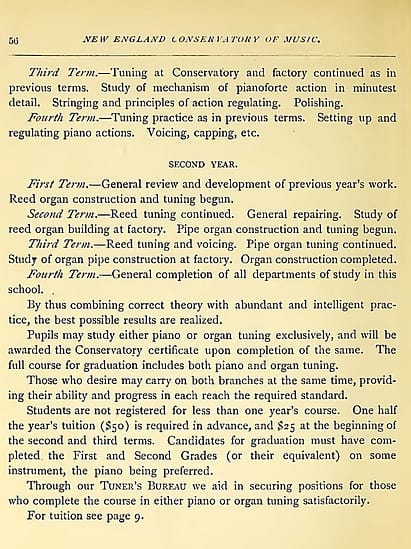

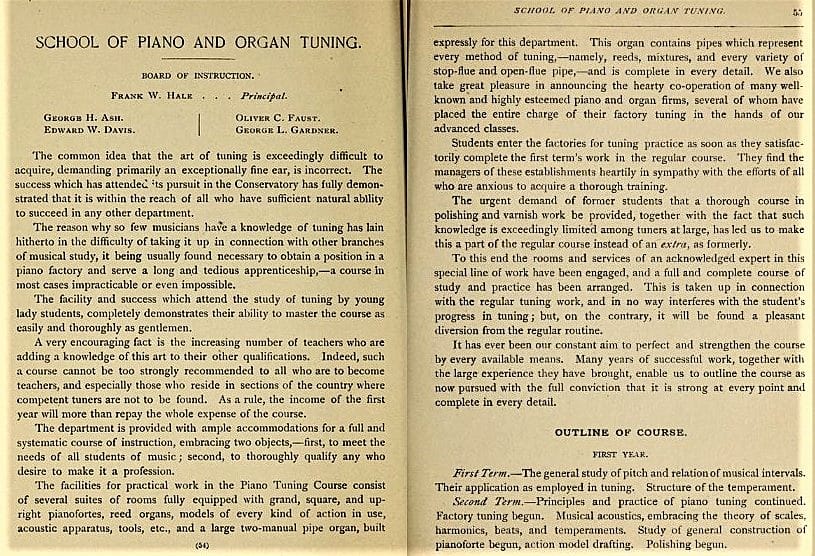

Francis Hale and Oliver Faust went on to work as colleagues at the New England Conservatory of Music (NEC), with Faust as an instructor and teacher of a piano-tuning program, and Hale as the business director and an instructor.

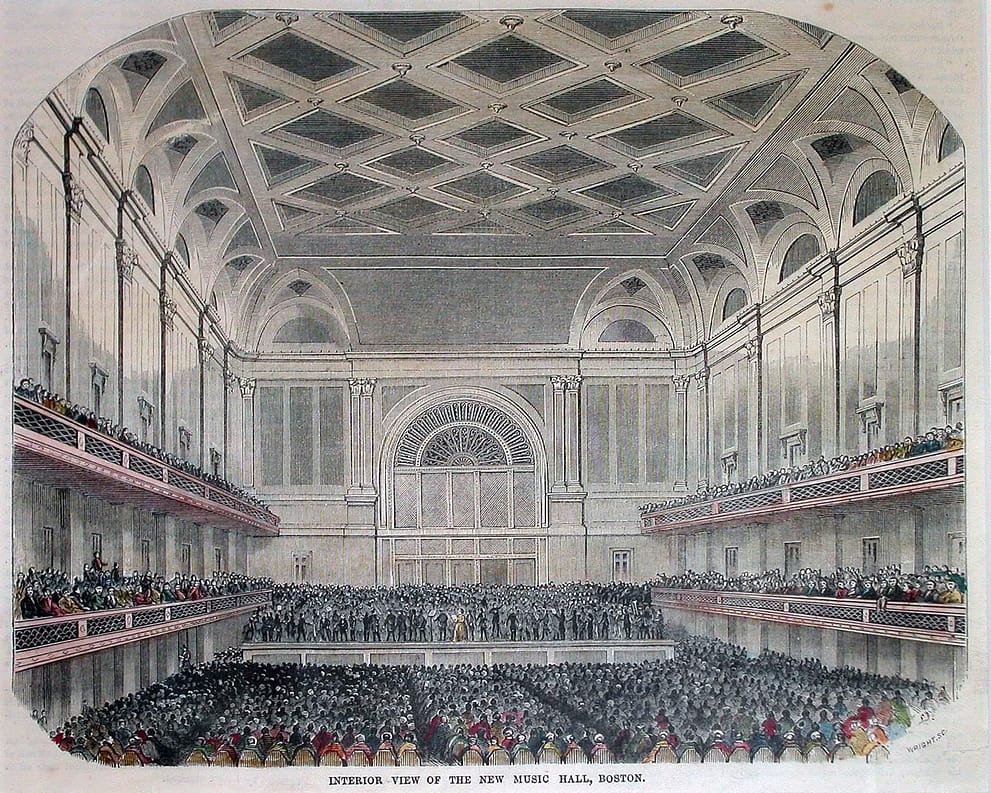

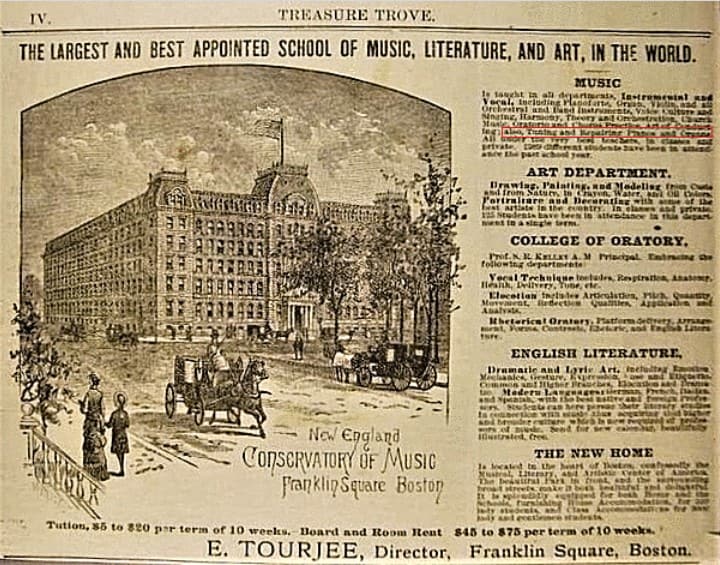

Boston Music Hall in 1867, now the Orpheum Theatre. The New England Conservatory was established on 18 February, 1867. The founder, Eben Tourjée, rented seven rooms above the Boston Music Hall on Winter St. (presently the Orpheum Theatre).

1895 Map of Boston by Bromley. Here you can see Winter St., and Boston Music Hall off of Tremont Ave. NEC remained on Winter St. until 1882, when they moved the school to the old Saint James Hotel (later, the Franklin House) in Franklin Square in Boston’s South End. The early “Winter Hill, Boston” address that appeared on early Tuners Supply Trade Publications was not near Winter St., off of Tremont Ave.; it was a neighborhood in Somerville,

NEC is on the South side of Franklin Square, and Hallet & Davis is on the corner of Harrison Ave. and East Brookline St.1895 Map of Boston by Bromley.

The New England Conservatory of Music, c. 1900. Frank W. Hale, General Manager. Post Card detail from NEC store.

Apparently, both NEC and Boston University (BU) College of Music were offering music classes at the Saint James Hotel. NEC started there possibly as early as 1870, and BU started in 1882. Regarding the NEC move to the St. James Hotel, there is a discrepancy between the date of 1870 given in Wikipedia, and 1882, as given in the BU account, as well as the NEC 1883 advertisement shown above.

Frank W. Hale was not only the manager/principal of the Tuning Department; he was General Manager of the entire NEC. Here is a description of Hale’s pivotal role at NEC, as described in his 1933 obituary: “While connected to the Conservatory, [Frank Hale] founded the first piano tuning department of the Conservatory. Later, under his direction as general manager of the school, [NEC] outgrew it’s quarters and moved to the present location on Huntington Ave.” NEC’s current address, 290-294 Huntington Ave., which includes Jordan Hall, was built in 1902.

Hale listed himself as a teacher at NEC from 1882 to 1890 in the Boston City Directories. From 1892 until at least 1903, Hale was listed as the “General Manager of NEC. ” NEC moved from Franklin Square to Huntington Ave in 1902-1903

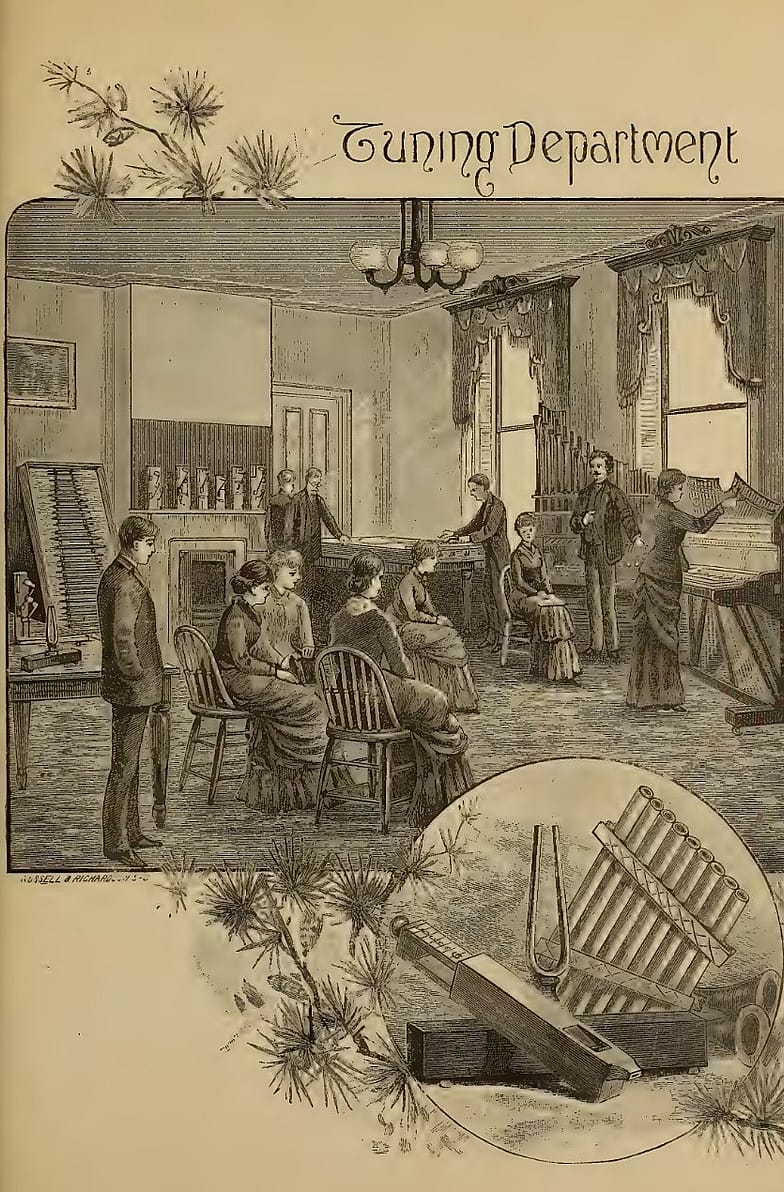

6 women students, 4 male students, and 1 male teacher (possibly Hale) shown in this illustration. New England Conservatory, Tuning Department, in the 1883 NEC Prospectus.

Sometime after 1890, but before 1893, Oliver C. Faust became a teacher of piano tuning. Tuning Department faculty, from New England Conservatory, 1890 Prospectus.

Here is the account of the separation of the NEC Tuning School in the 1945 Tuners Digest article on Faust: ” In 1910, The Conservatory dispensed with the tuning Department and Mr. Faust bought the property at 27-29 Gainsboro St. Directly across from the Conservatory, and established the Faust School of Piano & Organ Tuning.”

Oliver C. Faust “Teacher at New England Conservatory, and Faust School of Piano Tuning. 1937 Boston City Directory.

In 1922, Faust was again listed as a faculty member (tuning & organ construction) at New England Conservatory. This could have been before 1922, as I have not found documentation for the NEC Tuning Department after 1910 and before 1922. Faust continued as an NEC faculty member until at least 1940.

It looks like another Faust family member decided to tap into the conservatory formal clothing market. All of the students would be required to perform in multiple recitals; the men would need tuxedos and the women would need fine formal dresses. A good market.

Oliver C. Faust, in “The Tuners Digest, April 1945. Thanks to Fred Sturm, for bringing this to my attention.

From the 1938 Hale catalog. The connection between Hale and Faust was lifelong. A drawing of the $50 tuner’s kit is shown on the intro page.

New England Conservatory’s Tuning Department was pioneering for its time; NEC and Hale established the first residential piano tuning school in the United States in 1880. Remarkably, the NEC Tuning Program promoted the enrollment of women into the piano servicing field: “The facility and success which attend the study of tuning by young lady students, completely demonstrates their ability to master the course as easily and thoroughly as gentlemen.” In the 1880s, there was a significant percentage of women enrolled in both the Boston University Music Department as well as NEC. This high percentage of women enrolled in professional music programs was a direct outgrowth of the Victorian ethos around women of a certain class and ‘refinement’ learning about music and the arts.

Frank Hale developed his 1885 patent tuning hammer — which, when extended, gave added leverage –with women in mind. Hale saw the numerous women music students as potential enrollees in the NEC Tuning Program. Here is Hale’s description of this leverage advantage, in the NEC Tuning Department Prospectus for 1883: “The mechanical labor of tuning, which has heretofore been offered as an objection to ladies learning this art, has been reduced to a minimum by a recent invention which renders the tuning of the heaviest strings perfectly easy to the most delicate hand…”

In fairness, Frank W. Hale did not invent the extension tuning hammer. And there was no clear inventor of the extension feature on piano tuning hammers, although they were developed in the United States. Erlandsen extension hammers, which were introduced in 1863, had been the standard tuning hammer, and would remain so up until World War I.

Hale’s philosophy of introducing lightweight tools, as described in the 1930 Tuners’ Supply Catalogue.

Additionally, Hale paid attention to minimizing the size and weight of all of his early tools: with women in mind, but also for the purpose of easier mobility for tuners in general.Hale grand hammer extractor, and bronze hammer extractor.

Here is an example of Hale’s vision, as seen in his basic hammer extractor for mobile tuners, and used for spot removal of loose grand hammerheads. Hale’s extractor is smaller overall, with a comfortable paddle handle. It has a nice nickel plating on all parts, and has a brad point on the business end to prevent the press from ‘walking’ away from the end of the hammershank when being turned. When picking up one tool to compare with one other, the weight difference may not seem like much, but when an entire toolkit has been designed for compactness and lightness in weight, the difference is appreciable. Especially when carrying a toolkit on a necessary long trek in a dense city.

John Ford’s bronze extractor is also a good tool, however, and is more robust. Which is better? That is for you to decide.

Another advantage of the NEC Tuning program, was the collaboration with various piano factories, permitting students to gain experience tuning pianos in a realistic setting, unlike that of a practice room (1896 NEC Catalogue): “We also take great pleasure in announcing the hearty co-operation of many well known and highly esteemed piano and organ firms, several of whom have placed the entire charge of their factory tuning in the hands of their advanced classes.” I must admit, this sounds a bit overly optimistic to me.

In the earlier years of the NEC Tuning Department, Hallet & Davis, Pianomakers, at the corner of Harrison Ave and East Brookline St., Franklin Sq., Boston, participated in this arrangement with student tuners. D.S. Butner, an NEC Tuning School graduate described this opportunity in an 1892 Music Trades Review letter: “Just as soon as a student is able to tune a piano in a reasonable length of time, he enters Hallet & Davis’ piano factory. He is supposed to work one-half his time in the factory, and the other half in the Conservatory practicing and receiving instruction. When desired, his work is examined by one of the teachers, as is also the factory work every time when finished.” This student to factory collaboration was also carried over into the later Faust School of Tuning program, at the Chickering Piano Factory.

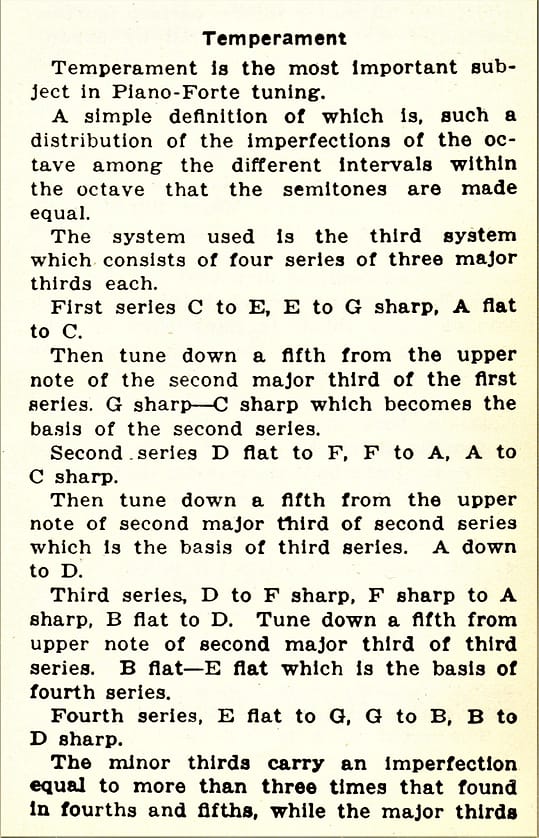

In the 1870s and 1880s, tuning practice in North America was based generally on temperaments using Fourths and Fifths. Frank W. Hale began the NEC Tuning program using a temperament based on Fourths and Fifths, but later transitioned to a Tenor C Temperament utilizing Thirds. Here is a description of this change in approach to tuning, in the Tuner’s Digest, April 1945: “Tuning at first was done by Fourths and Fifths, but Mr. Frank Hale and Mr. Faust worked on and introduced the Thirds system. At that time the factories would not believe that pianos could be tuned by Thirds, but the system finally proved itself.”

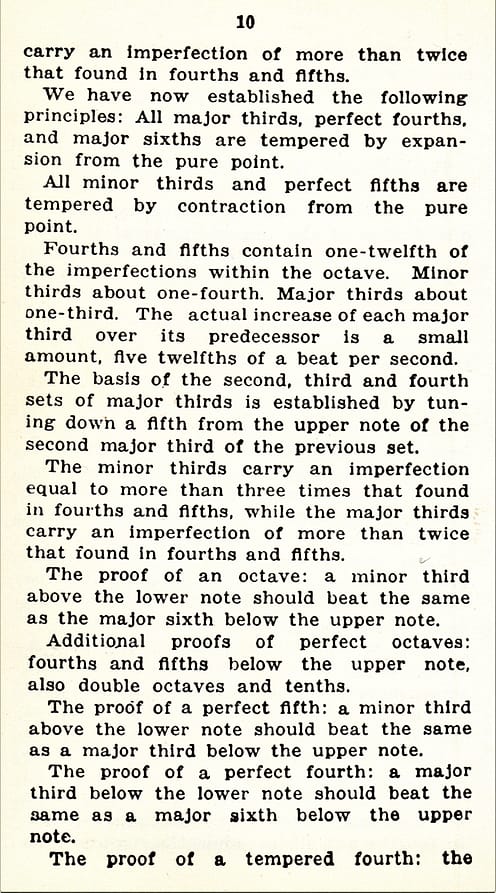

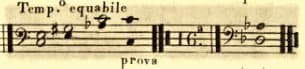

Here is the Tenor C Temperament as recorded in The Tuner’s Pocket Companion, which was essentially a transcription of Faust’s lectures given in the NEC Tuning program in the 1890s:

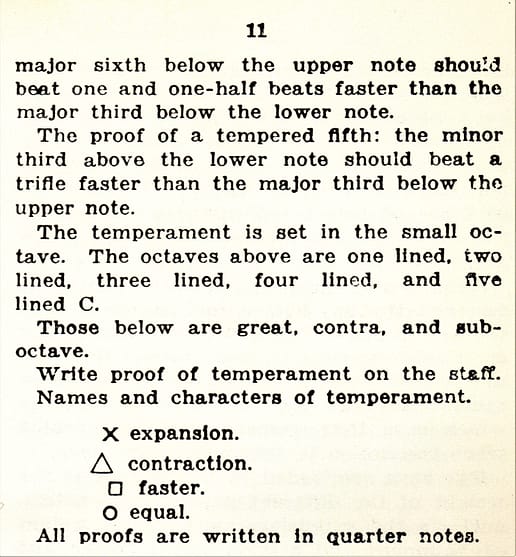

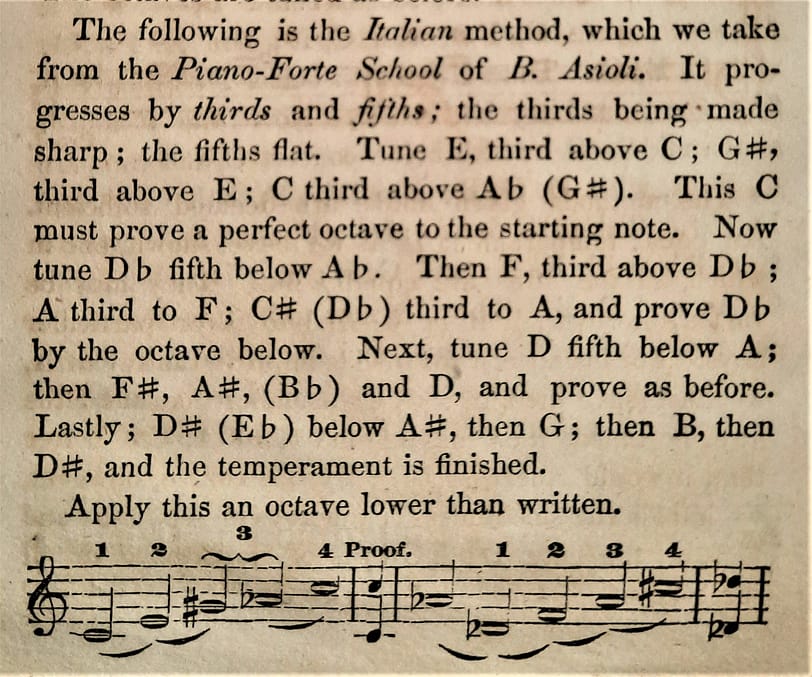

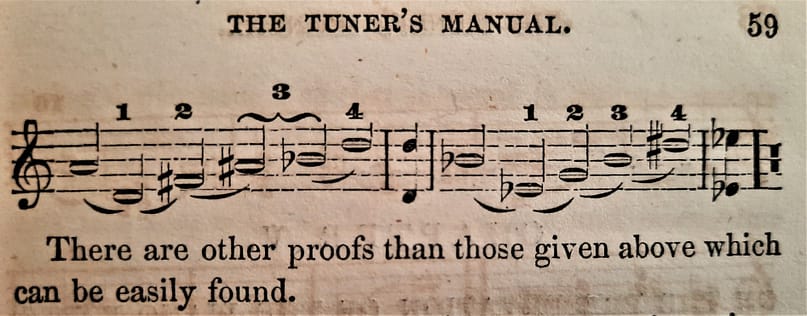

While Frank W. Hale introduced the Tenor C Temperament to his Tuning students in the late 1880s, this pattern did not originate with him, or with Faust, who taught later. The Tenor C Temperament had been circulating amongst tuners in the New England area since the 1850s, and possibly earlier. In The Tuner’s Manual, by Sumner Hill and O.B. Brown, published by Russell & Tolman, 291 Washington St., Boston, in 1859, the Tenor C Temperament was published:

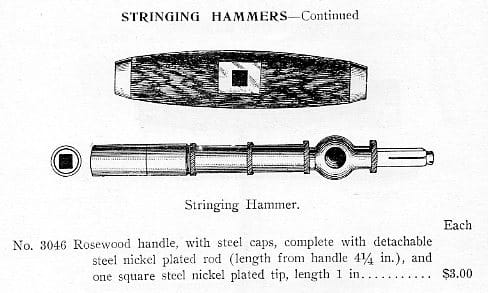

The Tenor C Temperament, as published by Sumner Hill and O.B. Brown, in The Tuner’s Manual, pub. 1859.

The Tenor C Temperament, as published by Sumner Hill and O.B. Brown, in The Tuner’s Manual, pub. 1859. (cont.)

Hill and Brown gave credit to Bonifazio Asioli for the Tenor C Temperament: “The following is the Italian method, which we take from the Piano-Forte School of B. Asioli.” Most likely, a piano tuner from Italy brought this temperament pattern to the Boston area in the 1840s or 1850s. It should be noted that the actual mid-19th century results of the Tenor C Temperament, in practice with period instruments, would not have been the accurate equal temperament that we have become accustomed to today.

Bonifazio Asioli introduced the Tenor C Temperament in his book, Observazioni sul temperamento proprio degl’istromenti stabili, (Observations on the Proper Temperament for Stability) which was published in 1816:

Bonifazio Asioli (1769-1832) was an Italian composer, harpsichordist, pianist, and musicologist, who was born in Corregio, Italy. He wrote several treatises on Music, including Observazioni sul temperamento proprio degl’istromenti stabili (1816). During his adult life, Asioli lived in Turin, Venice, and Paris. I would like to thank David Abdalian, RPT, who uncovered this history of the Tenor C Temperament, and then generously shared it with me.

Here is a translation of the Wikipedia Italia article on Bonifazio Asioli:

“Asioli was born in the then Principality of Correggio (now the province of Reggio Emilia) to Quirino, a watchmaker, and Benedetta Giovannelli in a well-known family of artists: his brother Giuseppe (1783-1845) was a talented [music notation] engraver, music lover and harpsichord player; another brother, Luigi, was a well-known pianist and music teacher in London, where he died while still young in 1816. The son of his brother Giuseppe, Luigi (1817-1877) who received the name of the late Luigi, was a talented painter; another brother, Giovanni, was a renowned organ player.

The precocious predisposition to music manifested itself when at the age of five he played by heart on a small organ that his father, a mechanical watchmaker, had built for him, a little tune that he had listened to during mass. The episode suggested to his father Quirino to find for his son a teacher who could transmit the first rudiments of music; then a certain Giovanni Battista Lanfranchi da Pomponesco, Mantua, was found, a teacher who proved to be mediocre. The young Bonifazio therefore grew up without a solid theoretical musical base and, endowed with an excellent ear, from the age of eight he wrote Masses; in 1778 he composed a 3-part Mass for orchestra and a 4-part Mass in E-flat which he himself sang in the church of San Quirino in Correggio. Given the ability of Asioli in writing music, albeit without a formal basis, the Municipality of Correggio raised the money to send the young Bonifazio to Parma as a pupil of Angelo Morigi, director of the Court orchestra and author of a counterpoint treatise; he continued his studies in Venice, Ferrara and Bologna where for a few months he was a pupil of Father Martini.

On 14 March 1786 he was appointed choirmaster in Correggio. He was the author of plays (The lively Contadina, The fickle, The discord, The rape of Proserpina, etc.); however, he excelled in sacred compositions (numerous masses, antiphons, litanies, motets, etc.) and instrumentals (five symphonies, chamber music, sonatas for various instruments, etc.).

In 1808, during the Napoleonic Reign of Italy, the first Royal Conservatory of Music in Milan was founded by decree of 18 September 1807 signed by the viceroy Eugenio di Beauharnais, the current “Giuseppe Verdi” conservatory: Asioli, one of the largest tutors of the time, was called to cover the unified positions of Director, Master of Composition and Censor. He held office until the fall of the Kingdom in 1814 when he was fired from the restored Austrian government for being a foreigner.

Among his pupils was Carlo Evasio Soliva. He also wrote treatises on music theory and didactic manuals.”

The Tenor C temperament pattern was taught to some tuning students in the Boston area for at least 130 years. The Pulsifer School of Piano Tuning in Newton, MA, was still teaching this pattern in the 1970s and 80s.

In their 1883 Catalogue, NEC wrote that it was difficult, if not impossible for musicians to obtain well-rounded training in the tuning and servicing of organs and pianos: “The reason why so few musicians have a knowledge of tuning has lain hitherto in the difficulty of taking it up in connection with other branches of musical study, it being usually found necessary to obtain a position in a piano factory and serve a long and tedious apprenticeship–a course in most cases, impracticable or even impossible.” Frank Hale and the New England Conservatory had definitely found a need, and filled it. It is important, however, not to look at the situation in 1880 with 2020 hindsight. Many “baby boomers” who entered the piano technology field in the 1970s, have witnessed the demise of the American piano manufacturing industry during their working lifetimes. And in the past 40-plus years, the Piano Technicians’ field has been increasingly concentrated around gaining employment within the music departments of educational institutions. But in 1880, there was a plethora (200 plus) of burgeoning pianomakers in towns all over the United States, and the learning opportunities for an energetic and enterprising young person should not be underestimated. For example, the piano factory job of a voicing/finisher would have exposed a young worker to action work, hammer tone building, and troubleshooting, and would also have involved learning about the structural components of the entire piano. Some experience in tuning, which could be gained through personal initiative, would be all that was needed to make such an individual an expert piano technician in the field.

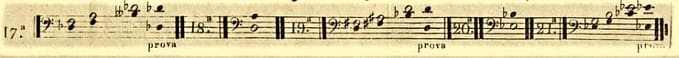

New England Conservatory of Music, Department of Piano Technology. Advertisement in “The Piano Technicians Journal,” October, 1979 (I was enrolled at the time).

Another example of a skill set transferable from piano manufacturer to independent piano work in the field would be piano technicians in Concert & Artist Departments. My own experience, as a graduate of the third iteration of the Piano Technology Department of New England Conservatory, but also having spent four years in the piano industry directly after that, working for Steinway & Sons, has informed my point of view on this.

The 1930 catalog mentioned the introduction of the detachable tips. The illustrations of the horse and carriage and the airplane underscore the dramatic changes that occurred in technology during the span of those years.

Tuners Supply, or Hale’s mailing address, was Winter Hill, Boston 45, Mass. Their actual address was on Wheatland St., in Somerville, MA. Various street numbers found –for the same location– are nos. 88, 89, and 94. I remember going there in person, on numerous occasions, during my student years in the late 1970s, early 1980s.

“In 1885, Frank W. Hale, then a teacher of Piano Tuning in the New England Conservatory of Music, was granted the first patent on an extension hammer with detachable tips. Since that time improvements have been made to keep this tool the leader and today is is known throughout the world as the most practical tuning hammer a tuner can own.”

ALBERT HALE

Albert Lyon Hale Sr. (1884-1965) was a son of Frank W. Hale. He left the Hale Piano Supply business sometime before 1918 and moved to Tacoma, Washington where he raised a family. In his 1918 WWI Draft Card, Albert declared his profession as an “Oil Producer…Manager Hale Oil Co. Mid-Continent Field.” Albert declared his profession as a “Mining Engineer,” in his 1930 and 1940 census entries: oil mining and ore mining, respectively.

Albert L. Hale’s 1906 tuning hammer patent. “In the style now in common use the breaking of this detachable portion is frequently the source of much trouble and expense, as the intersecting section must be milled or chipped out. This often results in ruining the threads of the head, causing the loss of the entire tool. In my invention, this is impossible.” This is the familiar patent that is marked on the tuning pin tips from the mid teens to the early 1950s. From 1906 to to the mid teens, the tips were marked in various other ways, some with the month and year, and some of the others with (Hale) Tuners Supply, Boston.

Hale tuning hammer set, c. 1905. Hale’s “T”, or stringing, hammer also featured a socket for the lever, which provided another lever head which was much taller and permitted more clearance over obstructions, such as plate struts and protruding screws, found on many pianos. This was a variation on the patented idea of a single head with multiple sockets.

Hale’s Tuning Hammer Tips through the years. A selection of Hale tips. The screw socket in the center,is a larger diameter, and was probably produced for a couple of years preceding the 1906 patent until 1908, and the one second from the left, with a smaller diameter screw threaded socket, was made after 1908 right up to the 1990s. The tip in the center left reveals a hollow cylinder, which , in addition to being more easily removed if broken, made it easier to temper the tip, permitting water to be forced up the desired fluted portion. Early tips, from the inception of the Hale hammer in 1885, had a male screw with the socket in the head, shown second to right. Two tips on the far left and right, are examples of the varying tuning pin socket sizes available:

Years of Innovation: 1904 to 1920

The Hale c. 1907-1909 model has a larger adjustment nut, a differently shaped handle, and most significantly, an octagonal shaft, which was a new way (for Hale) to prevent rotational slipping. Hale continued to use the octagonal shaft in their hammers until the early 1940s.

Hale 1910-1913 extension tuning hammer. This hammer feature a threaded tapered shaft, not entirely unlike Julius Erlandsen’s 1904 patent. Hale placed the threads towards the back of the tapered section instead of at the front, as in Erlandsen’s.

One of the very few advertisements from Hale, Tuners’ Supply, which emphasize the “Piano Makers” market. From “Tuners’ Magazine,” January, 1913.

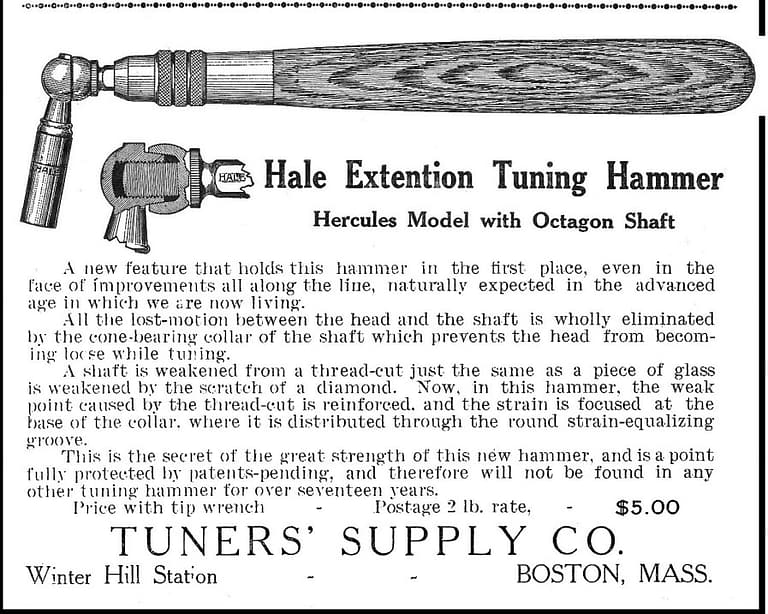

Hale Cup Joint Extension Tuning Hammer

“A new feature that holds this hammer in the first place, even in the face of improvements all along the line, naturally expected in the advanced age in which we are now living.

All the lost-motion between the head and the shaft is wholly eliminated by the cone-bearing collar of the shaft which prevents the head from becoming loose while tuning.

A shaft is weakened from a thread-cut just the same as a piece of glass is weakened by the scratch of a diamond. Now, in this hammer, the weak point caused by the thread-cut is reinforced, and the strain is focused at the base of the collar, where it is distributed through the round strain-equalizing groove.

This is the secret of the great strength of this new hammer, and is a point fully protected by patents-pending, and therefore will not be found in any other tuning hammer for over seventeen years.”

Hale Advertisement in “Tuners’ Magazine,” December, 1915.

Three “Cup-Joint” tuning hammers. This concept was put into production without the slot on the back of the head, shown in the patent illustration below, which would produce a pinching effect on the threaded part of the shaft, Top to bottom:1914-1915; 1914-1915; 1915-1925; 1924-1927. The hammer at the top of this photo is engraved with “patent pending,” which dates it to 1914–1915. Relatively early in the production run of the entire series of the Cup Joint model, c. 1914–1925, German silver was discontinued. The adjustment nut was changed to steel and the ferrule was made of nickel-plated brass, as shown on the hammer in the middle of the photo. The plating invariably wore through rather quickly on these hammers, but the steel adjustment nuts held up better than German silver under heavy prolonged use. This model still had the straight, not tapered, thread, which Hale phased out c.1925–1928. A cup on the shaft was eliminated in the version shown at the bottom of this photo, and a locking nut was used to secure the patented head instead. This tool belonged to the grandfather of my late business partner; he was a blind tuner.

H. E. Hale 1915 tuning hammer patent. Harold Emerson Hale (1889–1972) was another son of Francis Hale. In the 1930 census, Harold and brother Otis Cowell Hale (1897-1932) declared that they were managing a piano supply company (Tuners Supply). All three men owned their houses, as shown in the 1930 and 1940 census records, which is one indicator that the Tuners Supply business was profitable. Here is the patent for this design:

A wartime message (by Frank Hale’s sons) from Tuners’ Supply to their piano service customers. From “Tuners Magazine,” August, 1914.

More on Frank W. Hale

After finding success in the piano tool and supply business by 1900, a restless Frank Hale decided to try his hand at other ventures. Frank was able to indulge in other work because he was successful enlisting his sons, Albert, Otis, and Harold with running the day to day operations of the Tuners Supply facility in Somerville, Massachusetts. Following the resignation from his post as business manager of New England Conservatory in 1903, Frank Hale traveled around the western United States and Alaska, having adventures as a game hunter and promoter, from 1904 to 1910. After Hale tried his luck as an “oil man” in Washington and Oklahoma during and after the War years, Frank Hale returned to the occupation he really knew, which was pianos.

Its fair to say that Hale’s direct experience as a piano tuner technician gave him insight into the market during the first decades of the 20th century. Hale’s work history led him to the development of tuning tips machined to achieve a fit on a range of tuning pin sets unmatched by his competition. It was not just the interchangeable tips: the actual taper of the star socket–slightly less than some from other makers–made for a better average fit over a range of pianos.

Hale and Erlandsen Extension Tuning Hammers: a Comparison

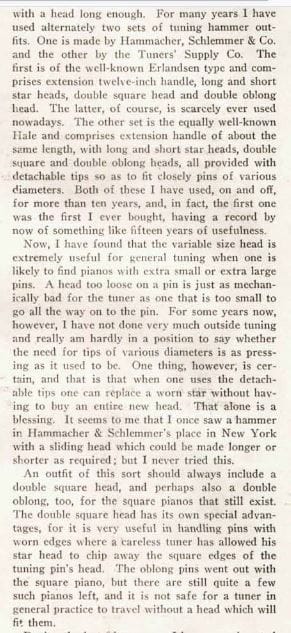

Any discussion of the Hale hammer in the early 20th century invited comparison with the long-established Erlandsen hammer, introduced in 1863. William Braid White (1878-1959), author of Piano Tuning and Allied Arts, 1917, Theory and Practice if Piano Construction, 1906, and A Technical Treatise on the Player Piano Mechanism, 1908, wrote the following comparisons of Hale and Erlandsen tuning hammers as a technical editor in the Music Trade Review:

While it is clear that William Braid White preferred the Hale over the Erlandsen, based on my research, an equal number of tuners preferred Erlandsen over Hale through the WWI era.

William Braid White went on to endorse Erlandsen, Hale, and Lang tuning hammers in 1920. “Music Trade Review,” 1920.

Erlandsen’s hammers and tools, dominant from the Civil War to about 1920, had superior build quality and materials on average, but Erlandsen lacked direct experience working on pianos, and the last level of insight into specific tuning and allied skills which would accompany that. Erlandsen’s focus, however, was on providing a wider range of tools and machinery for workers constructing pianos in factories, while Hale was interested primarily with the piano tuner in the field.

This was underlined by the fact that Hale never offered any hand planes other than the Stanley 101, while Erlandsen made a full line of mitre and rabbet (rebate) planes designed specifically for piano making applications. Erlandsen’s line of planes were among the finest ever made throughout the history of the United States

Other Hale Tools

As discussed earlier, Hale introduced a general downsizing of tools. Frank Hale also participated in the popularization (but not invention) of the adjustable tool handle for the mobile technician, introduced circa 1905. Hale’s unpatented voicing tool with swivel head (c.1916), allowing more hammer voicing to be done on uprights without partial removal of the action, was another important contribution. Modern tool makers in the United States, Germany, and China, still produce hammer voicing tools with the swivel head.

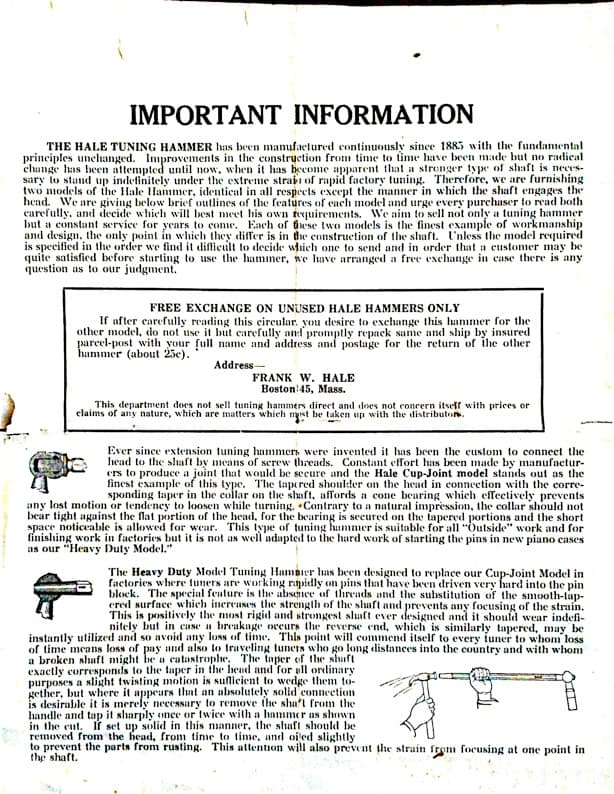

Other new items in the Hale catalogue included products such as the upright damper repair spring which hooks underneath the damper lever flange screw. New ideas were offered by Frank’s sons as late as the 1950s, such as the drum sanding collar for shaping hammers with a Dremel or Foredom type tool. This was an idea of controversial merit. Additional later innovations from Hale/Tuners Supply can be found on the Miscellaneous Piano Tools page..The Hale “Heavy Duty” Extension Tuning Hammer for Piano Factory Applications

Hale advertisement for Hercules Extension Hammer, and Factory Tuning Hammer, in the Tuners’ Journal, June, 1921.

Hale’s “Heavy Duty” model was introduced sometime before 1920, during the production of the “Cup-Joint” model. It is one of the few Hale tools that catered directly to the needs of the piano factory tuners, instead of the outside, or finish tuners. I believe that the ‘cup joint” model was discontinued, in part, because of cost considerations, and that the “heavy duty” model was discontinued because tuners had problems removing the heads from the shaft. Because of this heavy use, hand sweat would cause rust-freezing to take place, and the use of a hammer to release, an idea familiar to woodworkers, was not necessarily the case for tuners.

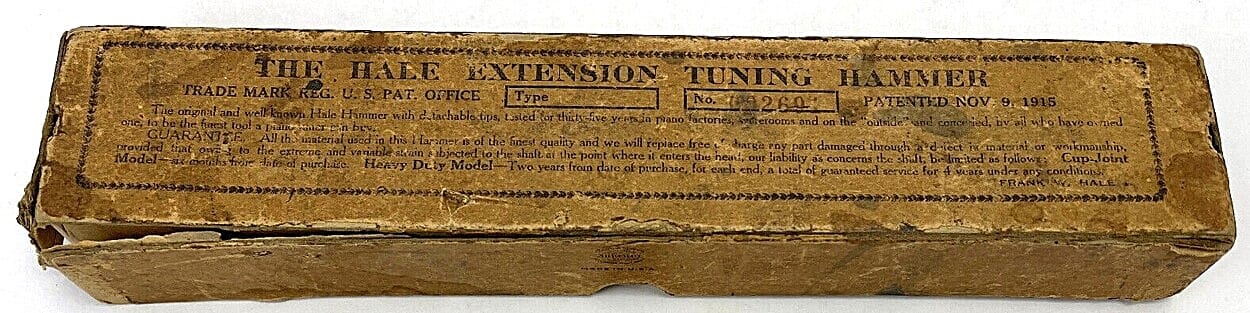

Hale Cup Joint Etension Tuning Hammer Box. Cup Joint: guaranteed 6 months. Heavy Duty: guaranteed 4 years.

Casemakers and bellymen would have been familiar with using the transferred shock of a hammer to separate, because that’s what is done in using hand planes for removal (in wedged planes) as well as adjustment of the iron. It was also true that the market of factory tuners diminished considerably during the span of the 1930s Great Depression.

It may not seem like Frank Hale was serious about guaranteeing his professional tuning hammers, but these assurances were made when–realistically–a whole lot more piano work was being done as compared to now. In four years of pitch raising pianos in a factory, a chipper would typically go through several tuning hammers.

Hale’s “Heavy Duty” model was introduced sometime before 1920. Thanks to Larry Lobel for this circular

Unthreaded, friction-fit “Heavy Duty” Hale model, c. 1920-1940. Hale’s “Heavy Duty” extension tuning hammer was intended for stringing, chipping, and rough tuning in factories. It was a user tool for me, and I worked with it every day, but not for all of my tuning work. The fact that the shaft goes all the way through the head and past the fulcrum of rotation, makes this arrangement as close as one can get to tuning with a “T” hammer, but still having the leverage advantage.

Hale’s incentivising message to Piano Tuners in the midst of the Great Depression, 1935 Hale Catalogue. Hale printed this message on the inside of the catalogue cover, which they did not typically do before or since

Short head bored through, no threads. When modern piano specialists see these for the first time, often their first thought is they have been buggered by an impatient predecessor. But that is not the case.

This is a good tuning hammer in most respects, but the nickel plating over brass–hard to make durable under any circumstances–did not hold up at all. I am thinking the reason that Hale switched from German Silver ferrules in 1915 to nickel plated brass pertained to the metals shortages during WWI. But Hale continued to use thin and flaky nickel plating in that application until returning to the German Silver ferrule in the early 1950s, for the late production runs of their “Artwood” tuning hammers. The steel thumbscrew–produced from 1915 to 1992– held up better than the pre-1915 German Silver Hale thumbscrews. Steel thumbscrews combined with German Silver ferrules were retained throughout the production of Hale’s grey Polypenco Nylon tuning hammers, circa 1957 to the closing of business in 1992. Hale would have been better off back then, just producing their No. 1 Hammer with a brass ferrule, like Watanabe in Japan did on their extension tuning hammer decades later,

A Unifying Approach: The 1/8″ NPT

“Cup-Joint” model was replaced with a 1/8″ tapered pipe thread on the shaft, which was phased in, c. 1925-1928. This idea combined the “cup joint” and “heavy duty” concept into one model. But the unthreaded ‘heavy duty” model remained in production until about 1940. This particular threaded model with octagonal shaft was offered until at least 1940, at which time the shaft was change to round with a fixing slot.

WWII and the Postwar Years

Post-War Business Conditions according to Hale Tuners’ Supply. From “The Tuners’ Journal,” December, 1946.

“Critical Materials,” shortages described by Hale during WWII. From “The Tuners’ Journal,” October, 1943.

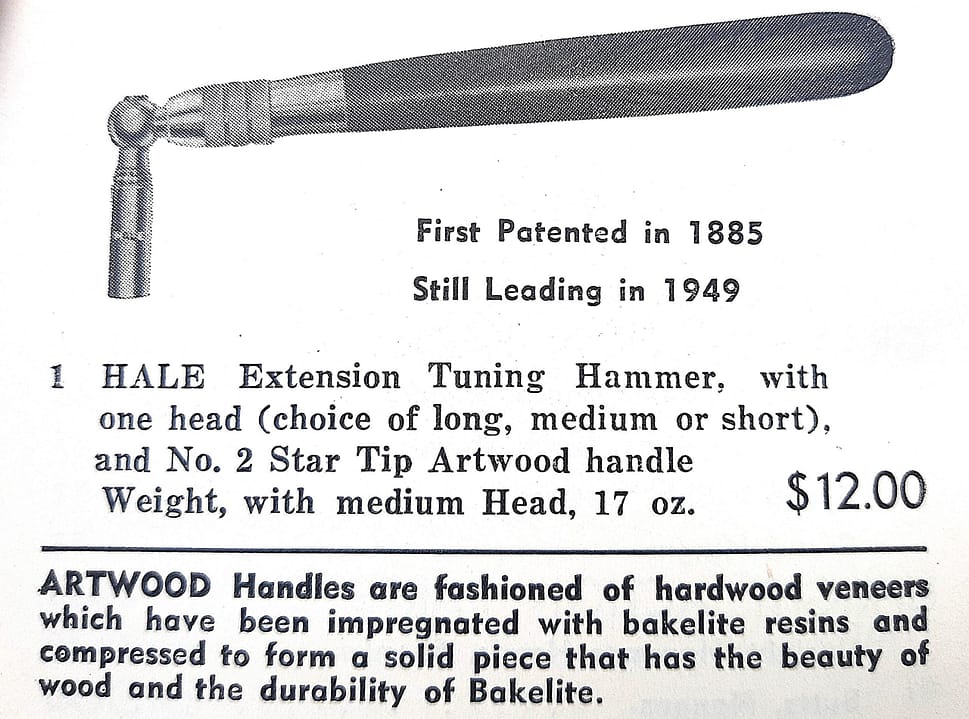

A Hale Tuning Hammer, shown at the bottom of this photo, made c. 1940–1945, was the last version to feature a rosewood handle, until Tuners Supply reintroduced rosewood as an option in 1986. This example has been shortened by a previous owner, probably Peter Wolford (1919-2005) of Marin County, California who bought it new. Hale returned to a round shaft, as used in their original version, and the shaft thread retained the 1/8″ tapered pipe thread (1/8″ = inside diameter of pipe), which allowed for limited ex-changeability between heads of different manufacturers. Early postwar models were made with laminated exotic hardwood veneers, impregnated in Bakelite resins—this was called “Artwood,” as shown by the two examples at the top of this photo. These handles are distinctive looking and are still in demand by tuners. Later models were made with grey Polypenco nylon and a nickeled brass ferrule. Otherwise, this model remained essentially unchanged until the sale of Tuners Supply to American Piano Supply Co. in 1992.

Two early “Artwood” Tuning Hammers, c. 1946-1953, and solid rosewood Tuning Hammer, c. 1941-1945, shortened by Peter Wolford.

In 1957, Hale’s T Hammer was still offered in “Artwood,” but the extension and stationary hammers had no specification as to what they were made of. Probably the first year for Polypenco Nylon.

Hale 1949 catalogue: “A Busy Corner In Our Modern.Shop.” Extensive use was made of belt driven machinery, which was actually technology used with the introduction of factory steam engines in the early 19th century. The 4 workers shown in this photo, were probably most of the staff of toolmakers working for the Hale family business. Hale’s staff was basically equivalent to Lang’s as an 1899 photo of C. H. Lang’s shop showed six men. Both Julius Erlandsen and Joseph Popping had six men working in their shops during 1897, as recorded by the “Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of the State of New York.” Six seemed to be the magic number for these small piano tool makers.

Two “Artwood” Hale tuning hammers. Bottom: nickel plated brass ferrule 1946-1953. Top: German Silver ferrule 1953-1956.

Hale hammer with round shaft and solid rosewood handle. This type was offered in small numbers during WWll 1940-45.

Obituary of Frank W. Hale, 18 October, 1933. Interestingly, no discussion was made of Frank Hale’s involvement in the tool making industry: his tool innovations and patents, or of his business activities in founding Tuners Supply Co. Hale’s obituary was focused on his roles as a teacher and administrator. I read it as an unconscious class bias of the time.

Hale

Tuners’ Supply: 1960 to 1992

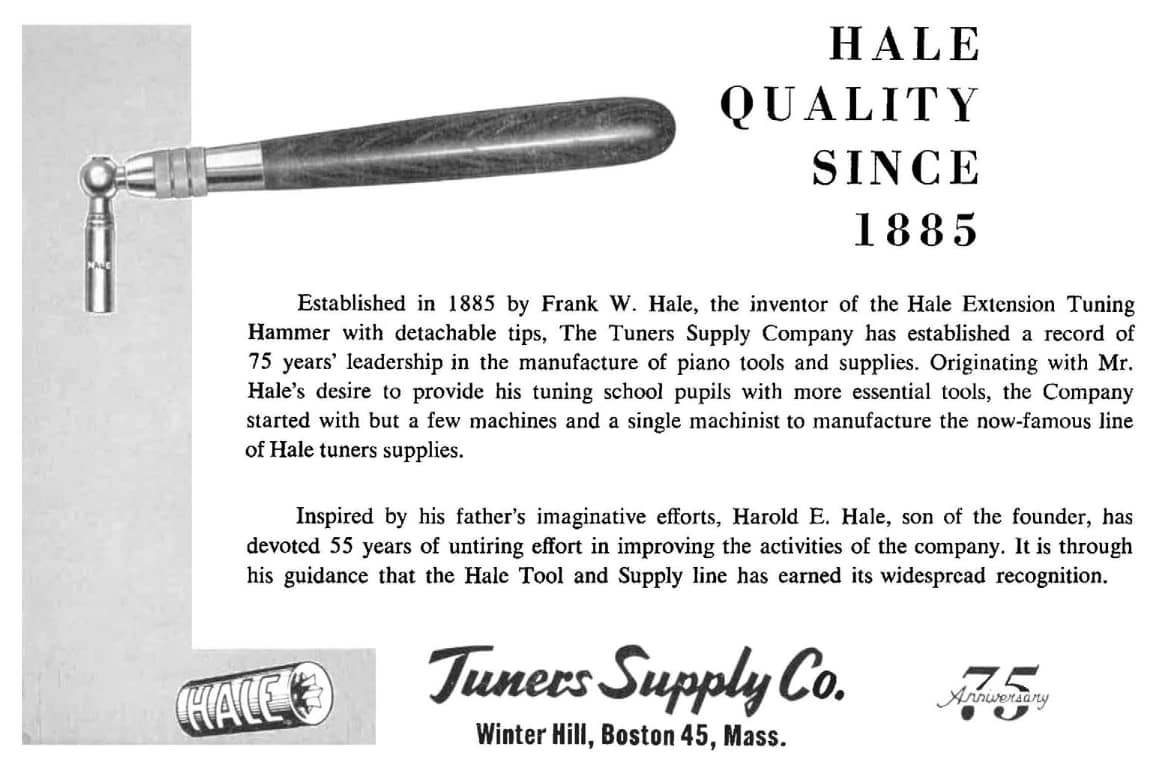

Hale advertisement in “The Piano Technicians Journal,” October, 1960. This 1960 Hale advertisement briefly described the early days of Frank Hale’s toolmaking at New England Conservatory. And it gave credit to Harold Emerson Hale (1889–1972)–inventor of the 1915 patent cup joint tuning hammer–55 years of dedicated service to Hale Tuners’ Supply Company.

Arguably, the Sight-O-Tuner (name influenced by the Conn Strobotuner) was the last major innovative product introduced by Hale Tuners’ Supply, in 1972. Dr. Albert Sanderson, the inventor, had problems with Hale making good on their end of the bargain:

“The Musicalibrator (later renamed the Sight-O-Tuner (SOT)) was originally invented and designed by

Dr. Albert E Sanderson in the early seventies as a prototype to tune pianos. The invention led to the

application and granting of eight patents on circuit design and the method of measuring

inharmonicity to create a tuning that took inharmonicity into account. The patent rights were later licensed to Tuners Supply to produce the Sight-O-Tuner. After a few years went by, there was an attempt by Tuners Supply to change overnight the reimbursement terms of the contract that led to a lawsuit. Those problems with the contract prompted Al Sanderson to redesign and start producing the Sanderson Accu-Tuner® in his basement. By producing the product himself, Dr. Sanderson had control over the quality and quantity of the units produced.”

–Paul Sanderson; Brian Day

In 1986, Hale reintroduced their extension tuning hammer in rosewood, for the first time since 1946. In calculating the 40 year hiatus, Hale did not consider their “Artwood” Tuning Hammers (1947-1956) as a genuine solid rosewood. Truthfully, while nice, Artwood was an early example of what we now call ‘engineered wood,’ all too familiar when assembling new furniture. The new Hale rosewood tuning hammers were not big sellers, nor was the Fairchild Speed Tuning Hammer, which was introduced in the late 1970s.

In 1992, Hale Tuners Supply sold out to Schadler /APSCO and they in turn, were bought out by Schaff Piano Supply in 2000.

“In 1992 American Piano Supply Co. purchased the assets of Tuner’s Supply Co. of Somerville, Massachusetts. Included in the acquisition were the production equipment and the rights to use the well-known “Hale” name. APSCO stocks a large selection of tuning hammers (including the

Hale) that they manufacture at their tool-making facility in Clifton, NJ. The Hale tuning hammer is available with or without the extension feature and with either a rosewood or nylon handle.”

David Severance, “Piano Technicians Journal,” January, 1997.

When Schaff bought out American Piano Supply in 2000, they also took over the in-house APSCO machine shop, and continue to operate that facility in Clifton N.J., making Schaff tools, as well as rebranded and modified “Hale” tools. Before 2000, Schaff relied primarily on (Rudy) Adams Machine Shop (A.M.S.) for the production of their piano tools.

“SCC acquired two parcels of land at 88 Wheatland Street in 1997 to transform what was an abandoned piano-parts factory into eight studio, one-, two- and three-bedroom condo units. The condominiums were sold in 2001 to low- and moderate-income first-time homebuyers through a lottery process. Priority was given to existing Somerville residents and minority families. The project continues to operate as an affordable condominium, with affordability preserved for future owners.”

Seven Tuners’ Supply Co. unmarked vintage hammer presses have been stored for years, and are now available for sale, and there are two models included: one for the underfelt, and a second for the top layer of hammerfelt. The seller wishes to see the hammer presses go to an individual who intends to use them to produce piano hammers, rather than to a museum or some other inactive capacity. Also, the seller prefers to sell all of the hammer presses together, rather than part out the collection.

Serious inquiries may contact me, and I will forward contact information to the seller.

Within the piano servicing space, there is, and has been, a great deal of attention and focus directed towards the ‘ideal piano hammer,’ and there may be some market for another domestic piano hammer maker, as much of the aftermarket hammer business is dominated by German and Japanese brands.