My interest in antique tools goes back to the late 1970s in Boston, even before my first commercial piano servicing work. In 1978, I took a risky hitchhiking trip from Boston to ‘Down East’ Jonesport, Maine, where I was excited to have found an antique piano tuner’s toolkit. Included in this kit was a double oblong tuning hammer, with rosewood handle, a Hale rosewood voicing tool with swivel handle, Erlandsen regulating pliers, and some beautifully machined regulating tools. I was hooked! It was early Fall when I was there, and the weather was already changing to cold, especially after dusk. One night, I slept in a densely wooded area not far from the rural route. Around three am., there was an intense downpour, which woke me up. All I could think about was: “oh no, these tools are going to rust!” Why did I write this study of historical piano tools? When I would go online in the early 2000s, there was literally nothing available, and yet I yearned to be able to read and learn about these antique tools. ‘When you want something done according to your wishes,’ the saying goes, ‘do it yourself.’ So I have tried to fill this niche, and have since been pleased to learn that traditional woodworkers, antique tool collectors, musicians, and piano workers of all kinds have developed an interest in these artifacts.

In these pages, specialized hand tools primarily for tuning, stringing, regulating, voicing, and repairing the piano, are covered. Elsewhere, there is more extensive information on tools which are used generally across the practice of a number of trades and applications, such as chisels, saws, and hammers. I have, however, included sections on hand planes, bit braces, pliers, and drills; in these cases, familiar tools were altered and specialized for the pianomakers.

In the small amount that has been written about this subject, much of it has been confined to genealogical and historical information about the makers and detail comparisons of the tools themselves. Most of this prior research pertained to the woodworking side of things–for those who had a general interest in antique tools. While I have included some genealogy and tool details on the pages within this site, I have also tried to include some of my own direct experience with the tools as a full-time piano craftsperson. A number of sections, such as Erlandsen Hammers, Bow Drills, Planes, Hale Hammers, Mutes, and Pianomaker’s Braces, contain some input on the applicability of the tools for piano work. For the more specialized tools, the very nature of the tools themselves define some of their usefulness.

Many specialized piano tools have been thrown away, probably because people in succeeding generations who have discovered these tools in storage, did not recognize what they were for, or if they did, could not find a use for them. Because of this, these tools have become relatively uncommon, considering how many must have been made to supply the massive piano industry between 1880 and 1930. Far more pianos from this period have survived, in comparison to the old tools made in the same years, that were created for working on them.

These pages on the topic of antique piano tools are devoted to the piano worker’s tools, not a history of the tuners themselves. For that, I strongly recommend Gill Green’s U.K. website on the History of Piano Tuning.

Antique and vintage piano tools, just as the pianos, generally reflect an old-world attention to detail. These tools utilized some of the best metals available, as well as fine-quality wood which was more common. These were the tools that were available and that were used by craftspeople on the pianos made during the heyday of the once-mighty U.S. piano industry, both in the factory and out in the field. Pianos were a featured subject of interest within the prominent classical music scene, the rise of the Jazz age, and in much of popular music.

Catalogs that I have read span the years between 1885 (Hammacher Schlemmer) and 1940 (Hale, Tuners Supply Company), primarily, but I do include a few postwar trade publications, as well as woodworking tool catalogues going back to the 1810s. Two things become apparent in reading the trade literature from these years. The first is the static nature of innovation and development in the piano-tool-making field, along with the pianos themselves. While this was a source of frustration for some engineers and engineering-types within the piano business, older traditional methods were retained because they essentially worked very well. Traditional building practice–and innovating within tradition– has always been a concept with paramount importance, not only in the piano industry, but in all music instrument-making.

Early extension tuning hammer, c. 1860s, with wheel thumbscrew, and “double oblong” socketed head.

As the 19th century progressed, many cabinet makers adopted the use of bench planes, infills, and shoulder planes, while piano workers still favored the earlier mitre planes and rabbet planes. Bow drills were still available to the piano trade as late as the onset of World War Two. And as ratcheting steel bit braces were utilized in post-Civil war America, piano workers stuck with their non-reinforced wooden pod braces, that were generally deemed obsolete at the beginning of the 19th century. Later, there was some change, much of it surrounding the advent of electric power, and the phasing out of some hand boring, cutting, and planing tools. Other developments came after World War II, primarily driven by the utilization of new synthetic materials in tool production, and the phasing out of rosewood and other hardwoods. The other constant in the trade literature is price; there is very little price increase for tools between 1885 and 1940. Compensating for inflation, tools became much more affordable as time progressed. For example, an 1885 Hammacher Schlemmer (Erlandsen) extension hammer with a star head sold for $7.80, while a 1940 Hale rosewood extension hammer sold for $6.00.

Early piano tool and supply catalogs published in the late 19th century were intended as much for the piano maker as the itinerant piano tuner, if not more so. The piano industry was growing and dynamic at this time, and piano makers could be found in cities all across the United States. A look at old city directories can confirm this.

IN THE FACTORY

At J.& J. Goddard’s in London, one could make an entire piano from the almost unlimited components, casework, and supplies available. In 1920, a builder could assemble a new straight strung upright with overdampers, and even purchase new sets of oblong tuning pins! And yes, new bow drills were available to drill out the wrestplanks for the tuning pins.

J.& J. Goddard’s Vertical Strung Backs. From 1920 catalogue.

These piano ‘kits’ were assembled by some established makers, but just as often by the ‘garret makers’ in Shoreditch and Saint Pancras, and other localities in London known for the pianomaking trade. These ‘garret makers’ consisted of one to a dozen workers, often working out their homes, and making just a small number of pianos per year.

In the beginning, makers like Cristofori would have made his pianos completely by hand, in much the same way as harpsichords were built in Italy during the early 18th century. With the Industrial Revolution taking off in the late 18th century, came great changes to how pianos were made. There was significant resistance to industrial progress and efficiency in England, however. To this point. Cyril Ehrlich, in “The Piano: A History,” (1976-1990) wrote that:

“…in Broadwood’s factory…machinery was almost wholly absent. The prevalence of hand labour throughout the industry must not be exaggerated. Even the eighteenth-century harpsichord maker was not required to reduce tree trunks to planks, and plane ‘great shaggy timbers to thickness.’ ” pp.18-19.

Ehrlich continued his description of this lack of mechanization:

“In England there had been no further progress in the mechanization of woodworking since the coming of peace in 1815, and existing machinery was ignored for forty years. During this period Americans, with abundant cheap wood and a shortage of iron and skilled labour, developed a wide range of machines for sawing, planing, boring, mortising and tenoning, introduced hundreds of special modifications for the manufacture of carriages, ploughs and furniture.” p.38

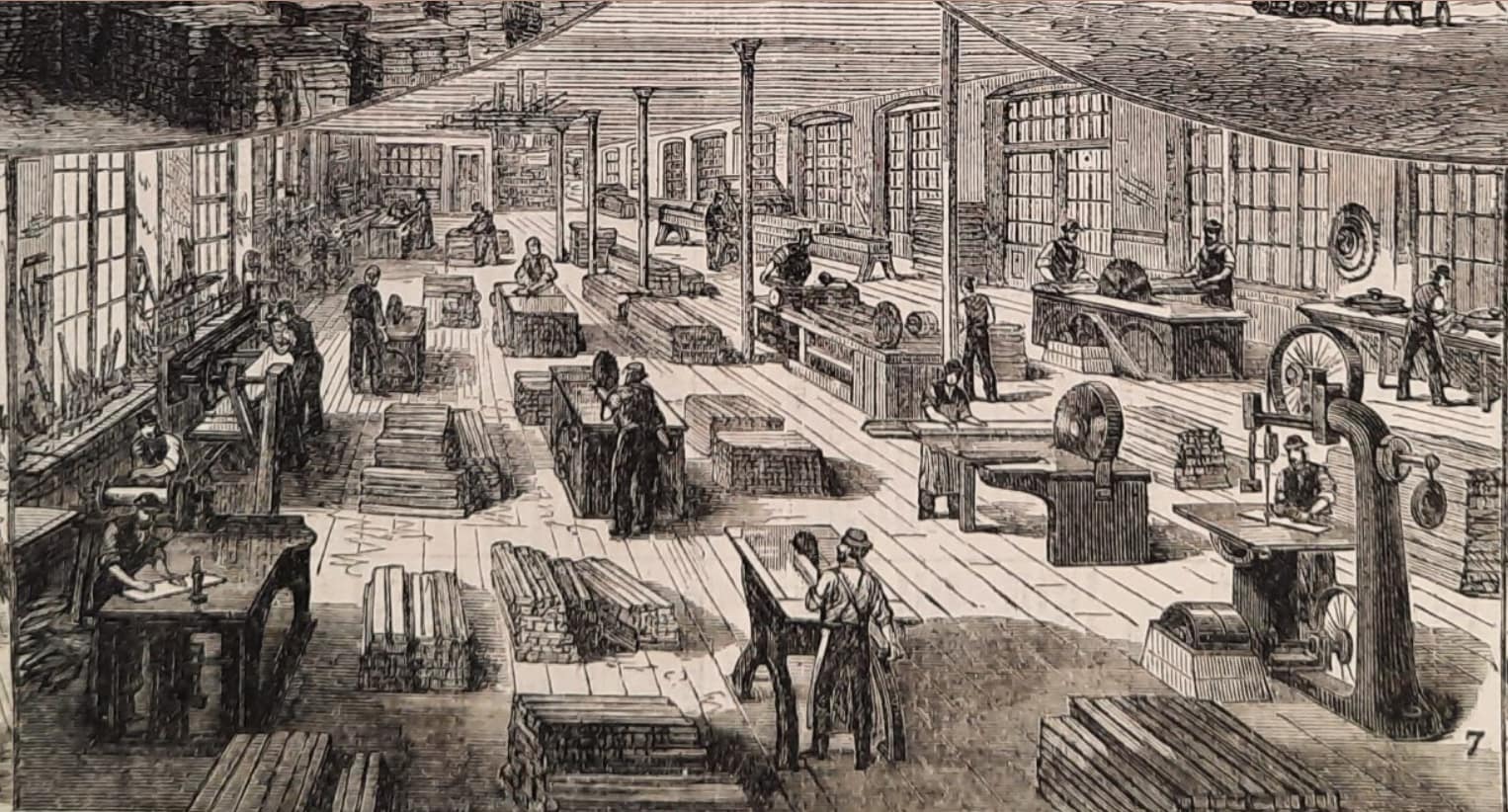

Machine Room in the Brinsmead Piano Factory in London, circa 1875.

While the piano industry in many countries was conservative, if not reactionary, regarding technological advancement, mechanization did make some inroads into the production methods of most piano makers. Even the backward-looking British piano industry adopted a certain amount of mechanized production methods by the 1870s.

The Brinsmead piano of the 1870s would still be considered very much a hand made piano, as hand tools for woodworking as well as mechanical work were required in the fitting, assembly, adjustment, and refinement of each instrument. That said, the 19th century piano was truly a product of the Industrial Revolution.

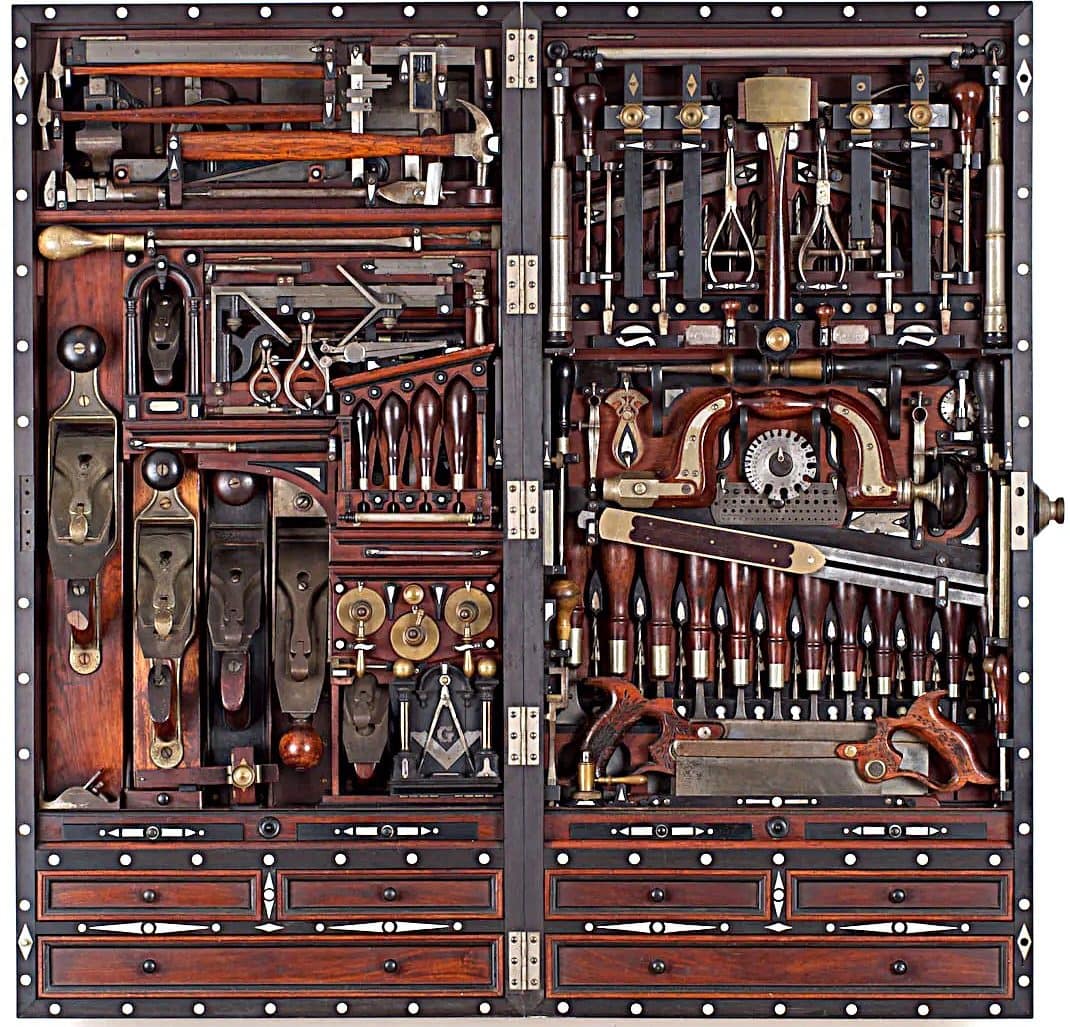

The now-famous tool chest made by Henry O. Studley (1838-1925), piano and organ maker while he was employed by the Poole Piano Co. of Quincy, Massachusetts, also reflects this diversity. Most of the tools here are general high-end cabinetmaker’s tools of the period. Visible tools that specifically apply to the pianomaker include a Stanley No. 9 mitre plane and a bow drill stock with small chuck.

Made from surplus mahogany, rosewood, walnut, ebony, and mother of pearl at the Poole Piano Co., the case holds about 300 tools and measures 10″ x 39″ x 19-1/2″ when closed. This remarkable achievement shows Studley’s great skill and devotion to his trade.

With the publication of the excellent book, Virtuoso: The Tool Cabinet and Workbench of Henry O. Studley in May 2015, by Donald C. Williams, we now know which particular specialized piano tools were included in the chest. The focus of the book, however, is on the build quality details of the chest, its tool contents, the subsequent provenance, and its hold upon the imaginations of those within the general woodworking community. Narayan Nayar provided many beautiful photos of the chest and its contents, which often drive the narrative of the book. Studley’s life history was also uncovered, with the assistance of a retired historian and a genealogist.

Studley married Abbie Stetson in 1870. In 1894, she became an heiress, inheriting from her father’s successful shoe making business. Both Henry and Abbie were active in managing their money, becoming involved in local real estate. Henry also sat on the board at some banks in their hometown of Quincy, MA. They had no children.

Many tools, including the Stanley planes, were purchased relatively early in Studley’s working life, first as a cabinet maker, then as an organ builder at Smith Organ Co. (~1874–1898). Studley worked at Poole for the last 20 years of his working life, c. 1898 to 1919.

These are Studley’s specialized piano tools held within the chest:

- Starrett 5-1/2″ wire cutters

- Starrett No. 280 music wire gauge

- General action wire bending tool sold by C.F. Goepel (made by Erlandsen)

- Two similar wire benders specified as backcheck wire benders in the catalogs of the time, but now are used primarily for upright damper wire adjustments

- Let-off, or escapement regulator, ~9″ long with handle–for uprights

- Felt cutting knife, also used for leather cutting

- Upright spoon bender, round shaft type, with hand made combination regulating tool handle, thumbscrew arrangement

- Hammer return spring/damper lever spring tool for upright pianos, 6 1/8″ blade

- Specialized pliers with 1/2″ jaws, which were set 3/8″ apart, possibly for hammerfelt compression if the jaws close to less than 3/8″ apart

A Little Victor block plane, sometimes found in 19th century piano supply catalogs, was also included. Also found was an “organ regulating device,” which looks to me like a custom reed slip, made from scratch. All told, its a rather small selection of tools for a specialist.

General woodworking tools, included in the chest, could have been used for casework, bridge and soundboard construction, wrestplank fitting, and other structural work. The specialized piano tools included—as well as those omitted—give indication that Studley was an action regulator on upright pianos. There were no grand action, voicing, or tuning tools in the chest—not even a tuning hammer for stringing/utility purposes, which would have established a connection with the Starrett wire cutters and music wire gauge. Traditionally, a voicer in a factory voicing department would not be taught how to tune, as this would be considered a distraction from the numerous responsibilities of the job, which included refining of the action as well as optimizing the final tone of the instrument. While the worlds of tuning and voicing touch each other, those within the action department per se were in a position considered more remote from the notion of tuning. Perhaps some of the omitted tools were placed down in the workbench cabinet, but most of these tools, which were relatively small, would not have been excluded for space reasons alone.

In a Dec. 17th, 1921 Music Trade Review notice for Studley’s 83rd birthday, a reference was made that Studley’s position at the Poole Piano Co. was “the head of the voicing department at the factory.” An earlier Music Trade Review feature article shown in Virtuoso on page 22, circa 1919, showed Studley standing next to his famous wall mounted tool chest and a Poole upright piano, the subtitle of the article stated that H.O. Studley was “in the piano business for over 46 years.” We know, from the thorough research in Virtuoso, that Studley’s entry into the piano business began with his tenure at Poole piano, circa 1898. The accuracy of the MTR articles are somewhat questionable, therefore, which introduces uncertainty whether or not Studley was actually the voicing department head, given the partial evidence shown in his tool chest. Its possible, understanding that Studley was an older, wealthy man before he began working at Poole, that his position there was to some extent, emeritus. Perhaps he invested in the Poole Piano Co., and participated in its profits. This would explain how Studley sourced the expensive exotic hardwoods and mother of pearl from Poole, as well as find the time to conceive and construct the cabinet; considering his relatively advanced age, it would have been increasingly difficult to undertake such a project outside business hours, in addition to his full time job and commute. It would also explain how Studley began his piano making career at the startup Poole Piano Co. already in a supervisory position, if indeed that was the case.

Also of interest is Studley’s specialized workbench vise, which features a revolving wheel for opening and closing the vise, instead of a typical sliding lever arrangement. Vises with the wheel adjustment were used in the piano industry, to the extent where they were associated with the old factories. One of these adjustment wheels can be seen further down this page, in a Winold Reiss 1931 mural of the Baldwin Piano factory in Cincinnati.

Key Leveling in the Steinway Factory, circa 1918. (LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, Steinway collection. La Guardia College (CUNY)).

This photo is from the Steinway and Sons New York factory circa 1915–1920. It is rather unusual to find historical photographs of piano factory workers where the actual work performed can be seen clearly. Part of this is due to the long time exposures made necessary by the very slow plate and film emulsions available before 1930.

To accommodate this, employees would stop working, line up abreast, and pose in front of the camera, which was mounted on a tripod. Posing for the camera, necessary from the beginning of photography, and into the early 20th century, became a traditional practice and a matter of habit. In the cases of old photos where workers were at their respective work stations, they would often be asked to hold in place, and also, views of the workers would be too far away to make out what they were doing specifically. Margaret Bourke-White did an outstanding photo shoot inside the Steinway Factory for Life Magazine in the mid-1930s, and these photos gave beautiful views of work being done. (LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, Steinway collection. La Guardia College (CUNY))

In the foreground of this photo is a regulator (wearing a kippah) sitting on a very low stool, leveling keys at eye level. The leveling stick was planed slightly concave starting from both ends, making an inverse crown in the center. When the keys were ‘level’, they would have a slight crown in the middle. It is still part of standard practice today. Joe Bisceglie made key leveling sticks for several Steinway Hall technicians, including myself, while we were spending a week with him in the factory. It was impressive how fast he could make them, using a handplane to create the slightly concave key leveling edge. I continue to use the key leveling stick that Joe made for me to this day. In the background, you can see another regulator, blowing manufacturing debris out of the piano with a special piano maker’s dust bellows. The piano action is sitting on the workbench behind him.

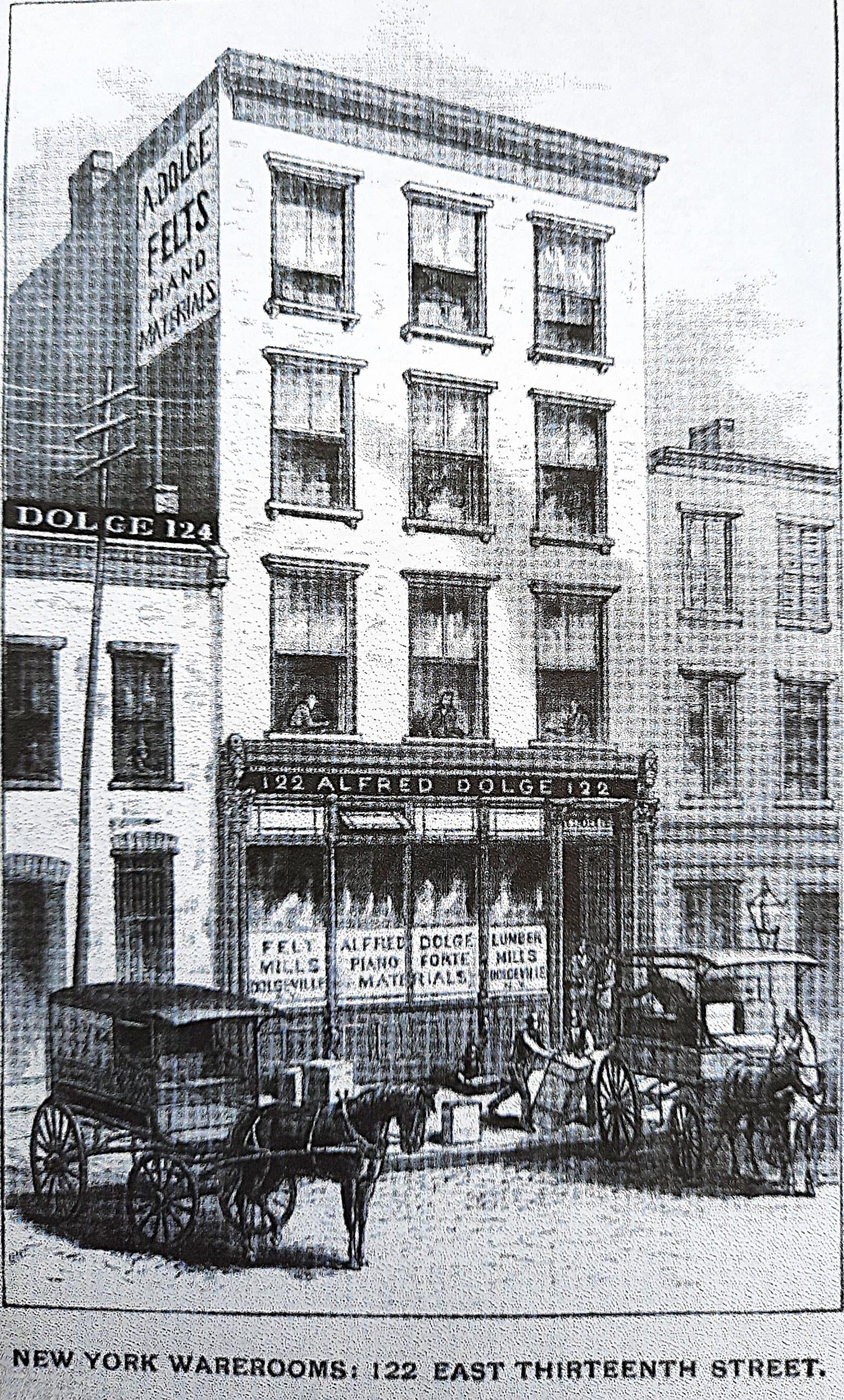

Alfred Dolge, 1892 (l.). These bellows were as unique to the pianomakers as the blacksmith’s bellows were for the smithing trade.

Alfred Dolge Soundboard and Felt Factory Complex, as shown in the Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue, 1869–1892.

I still use a cylinder bellows for blowing out debris underneath piano plates on grand pianos, especially when foreign objects on the soundboard make noise during playing. It sure beats carrying around a heavy air compressor. I bought mine new from Bob Wolf in 1982; Bob was a wonderfully kind older man who worked for John Ford’s piano supply company in New York City.

Ford’s supply house was on my way home from work, and I would stop in often, as it was adjacent to the subway stop that I disembarked from. Bob Wolf also administered the Piano Technician’s Guild bench test to me in the Fall of 1983. This square type pianomaker’s bellows was the original version from the 19th century, after which, the cylinder bellows was used, until the introduction of compressed air. But the cylinder dust bellows continued to be offered by suppliers, including Goddard, Baker, Fletcher & Newman, and John Ford. Even today, the pianomaker’s bellows are available for the piano and organ trade. The bellows are resting on a 19th century workbench with full cabinets. In the background is a Thorested-type rabbet plane which was designed for the growing piano industry in the late 1850s. Dolge developed a hammer press that is still in use today, and provided many components for piano builders, as well as piano tools and supplies for the industry.

When I worked for Steinway in New York in the early 1980s, I had the opportunity to meet a number of colleagues who had experience working at other N.Y. piano factories, such as Sohmer and Janssen. My colleague, Terence Walsh (1954-2017), whom I worked with at Steinway Hall for several years, moved on to Final Voicing Inspector at the Steinway factory.

Mr. Walsh came to Steinway from Baldwin’s C.&A. department in New York. Sohmer and Steinway employees were members of the same union, and Masuru Tsumita, one of my mentors, came over from Sohmer well before the firm moved to Connecticut. Tsumita later became head Piano Technician for the Juilliard School.

Despite the fact that I had a full time union job at Steinway, I’d still moonlight to save money. One of the many after-hours jobs that I did was installing a new bass bridge in a Steinway “I” upright. John Ford, owner of Ford Piano Supply in the Inwood section of Manhattan, expertly duplicated the old split bridge, using maple from the lumber stock of the old Krakauer Piano factory in the Bronx (corner of 136/137th Avenues and Cypress), which had closed for good back in 1977. John Ford himself, had worked for some years at the Mathushek factory in the Bronx (corner of 132nd and Alexander Ave.).

Krakauer spinet piano, made in the Bronx factory circa 1952, with beautiful ivory keytops, and a Kelly plate, which was well japanned under the smooth gold finish. Detailing on the plate was done in black lacquer with an artist’s brush. As far as spinets go, this is one of the nicer ones made, in my opinion.

It is clear that the people making Krakauer pianos really cared about their instruments, despite the increasing social and economic odds against them in the years following WWII. I have much respect for their efforts.

Unfortunately, the possibility of switching jobs from one piano manufacturer to another is long gone, with only Steinway, Mason Hamlin, and Walter remaining in the U.S. Great Britain, France, and Russia have very little, if any, piano manufacturing going on presently. Japan and Germany still retain a viable piano industry, but with somewhat scaled back plans. China has the most healthy, and expanding piano industry at this point, and its growing middle class has an interest in the acoustic piano. But many of the factories in Asia are pretty automated, far from the handmade pianos of the U.S. and Europe. Much of the reason I have mounted this presentation of antique traditional hand tools used in piano work is to make some record of this particular vocation: it’s part of a world that is gradually being left behind.

From George Dodd’s “Days at the Factories,” published 1843. Pictures from the Broadwood factory in London, drawn during 1842. Lumber, for seasoning and/or storage, was suspended from the ceiling. It’s good that there has only been a minimal history of earthquakes in Britain.

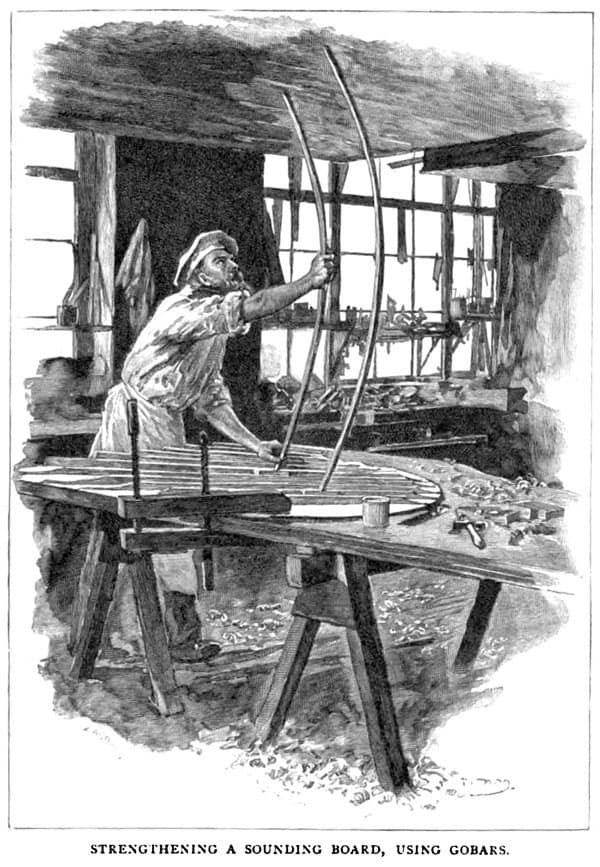

Worker using a bow saw to cut out the keysticks from flat stock of pine or spruce, which has been marked out. When visiting the Pratt Read factory in 1979, I saw keysets being cut out on a large bandsaw, also freehand.

Tuner in frock coat, working on a “Cabinet Piano,” in 1842, and using what appears to be a “T” hammer for tuning this cabinet piano: a piano type (1805–1850) which had long strings extending to the floor in the bass section. Note the long stickers or abstracts that span the distance from the back of the keys to the action itself, which was mounted very high on the piano in order to reach the correct strike line for the hammers.

Winold Reiss’s 1931 mural of workers in the rim department of the Baldwin Factory on Gilbert Avenue in Cincinnati, Ohio.

From “Popular woodworking.”

Winold Reiss’s 1931 mural of workers in the rim department of the Baldwin Factory on Gilbert Avenue in Cincinnati, Ohio. The Baldwin mural was one of a series of 14 murals of workers in industrial settings in the Cincinnati area. Originally, the murals were housed in the Union Train Terminal, but then they were moved to the Cincinnati International. Airport. Nine of the Reiss murals are in wings of the airport that have been closed and are intended for demolition, so those murals now face an uncertain future. A couple of planes are on the bench: it looks like they are an American metallic rabbet plane and a wooden toothing plane, and wood shavings have fallen to the shop floor. Clem Vonderheide (1897–1975) was inspecting the a rim, shown in the back, and Henry Wesserling (1870–1944) was running a sanding block around the inside of another rim. Established in 1891, by 1913, Baldwin was exporting pianos to 32 countries. Now owned by Gibson Guitar Corp., after two bankruptcies, Baldwin pianos are made in China, but with different scale designs.

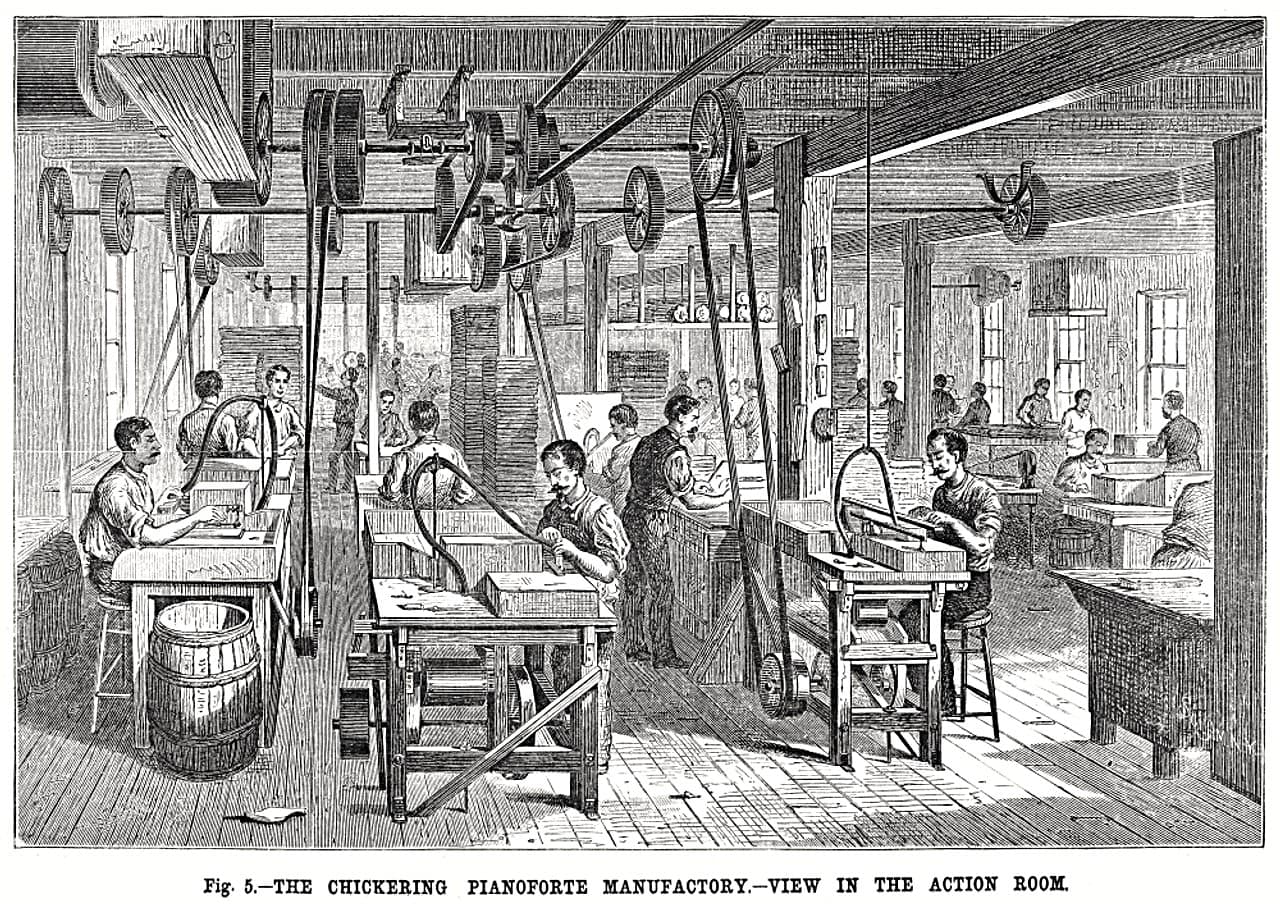

Chickering factory floor, Action Room, showing extensive belt driven machinery. 1878. And pair of “identical twins.”

Pleyel Wolff et cie, view of factory floor. From Les Grandes Usines Vol. 2, by Julien Francois Turgen.

In the Field

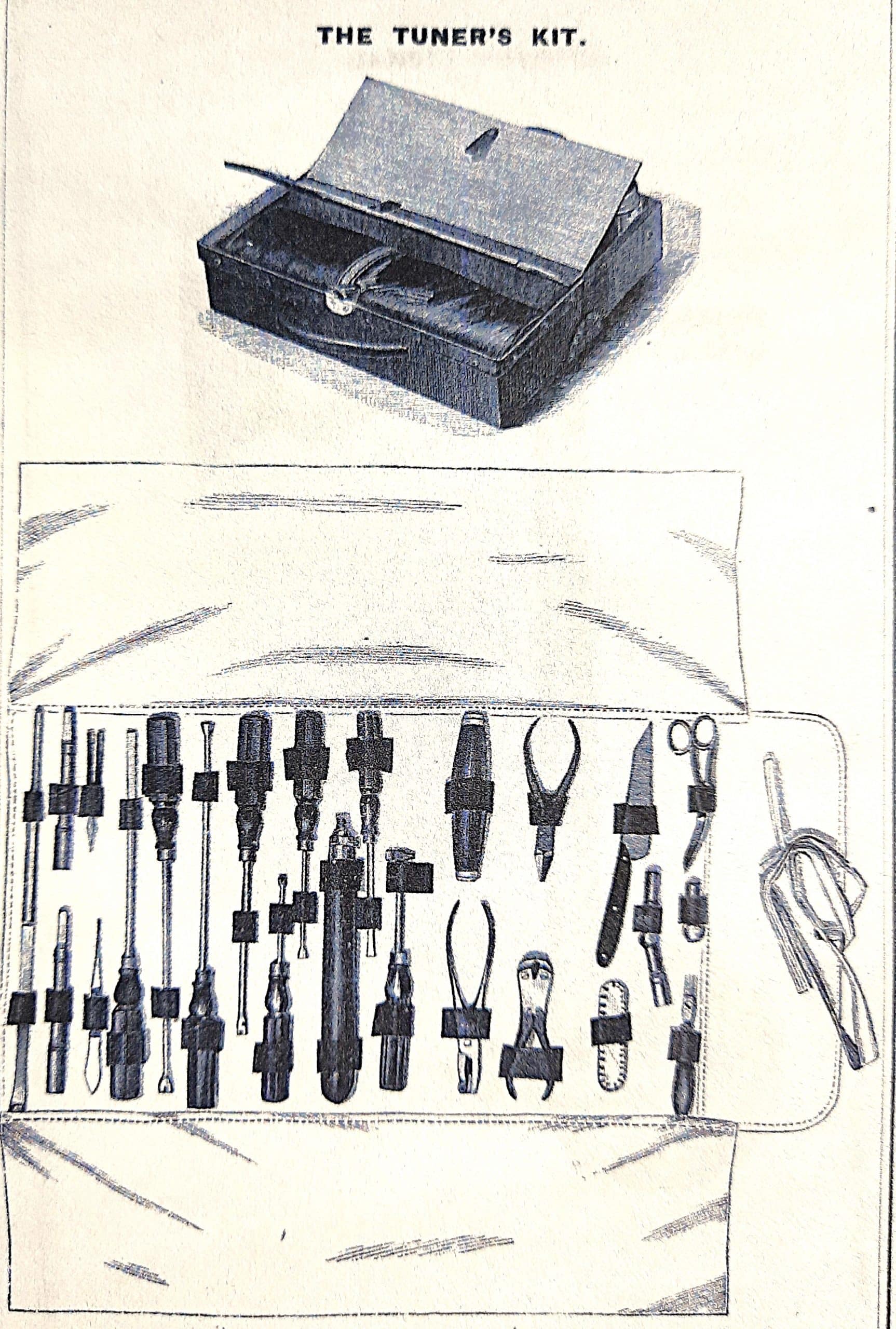

In the supply catalogues, tuner’s tool kits were available, usually contained inside a leather tool roll. The 1885 Hammacher Schlemmer tuner’s kit (pictured) was $26.00 and the 1940 Hale kit was $50. The Hale kit was somewhat larger. When looking at these kits, I think of the great musical milestones of the early 20th century involving the piano, and how the artists’ piano-related needs were met: without software to tell us where to put the notes, GPS to tell us where to find the customers, and carbon fiber levers to help us move the tuning pins securely. Of course, during the period between 1880 and 1940, the sheer numbers within the talent pool for piano specialists in manufacturing, and in the field, were larger than at any time before or since. Here in the San Francisco Bay Area, piano technician Richard Hornung comes to mind: at their peak, his family was installing 100 soundboards a year. And before the 1906 earthquake, there were up to 40 pianomakers in the San Francisco area. Even though the West Coast was never a large piano manufacturing center like the Northeast, there was much more bellywork—and all phases of piano work for that matter—going on then, as compared to the present day.

Tuner’s Kit, from H. S. & Co. Catalogue for 1885.

Hale Tuners Supply Complete tool kit for $50 in 1940. Among other things, a voicing tool was omitted from this “complete” tool kit

Tollner’s upscale wareroom in 1848. This illustrates the fact that fine tools in the mid-19th century had an elevated value, not just monetarily. Moseley & Son of 17-18 New Street, Covent Garden, London, provided the example of how to market tools in a posh environment. Moseley’s Covent Garden showroom was located in a retail district of London in the 1830s. The building still stands.

You may notice that I do not include pages for suppliers, such as Hammacher Schlemmer, C. F. Goepel, Schley, American Felt Co., Lyon & Healy, etc. It’s because these businesses were essentially dealers, and, in the cases where they had a machine shop, such as A.F. Co., and L. & H., the machine shops were producing derivations of the original toolmaker’s work. This website is devoted to the original piano toolmakers and the tools that they made. I first became interested in vintage and antique piano tools during the course of my early exposure to the piano trade in the late 1970s. From the late 1970s until the mid 1990s, and the beginning of the Internet, I came across old tools almost passively, taking advantage of the opportunity to acquire them as opportunities arose.

It is common in the piano-tuning trade for tools and equipment to be sold or passed on when a tuner retires or passes away. I met many older experienced tradesmen in the piano business during the early years of my working life: during the time of my training, while working in several used-piano stores as a student in Boston, during my years at Steinway Hall in New York City, and during the first five years that I worked in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Hammacher Schlemmer Piano Supplies Advertisement in Music Trades Review, 1900.

Hammacher Schlemmer & Co., 209 Bowery St., N.Y.C.

C.F. Goepel advertisement in the “Music Trade Review,” 2 October, 1897.

Quotation from H. S. & Co. in the “Music Trade Review” during 1907. Because Tollner, Hammacher, and Schlemmer relied on fine toolmakers such as Lauritz Brandt, George Thorested, Napoleon/Julius Erlandsen, and Joseph Popping, there was actually little to worry about as far as quality was concerned. But it does sound impressive, showing they had 19th century ‘dealer-speak’ mastered.

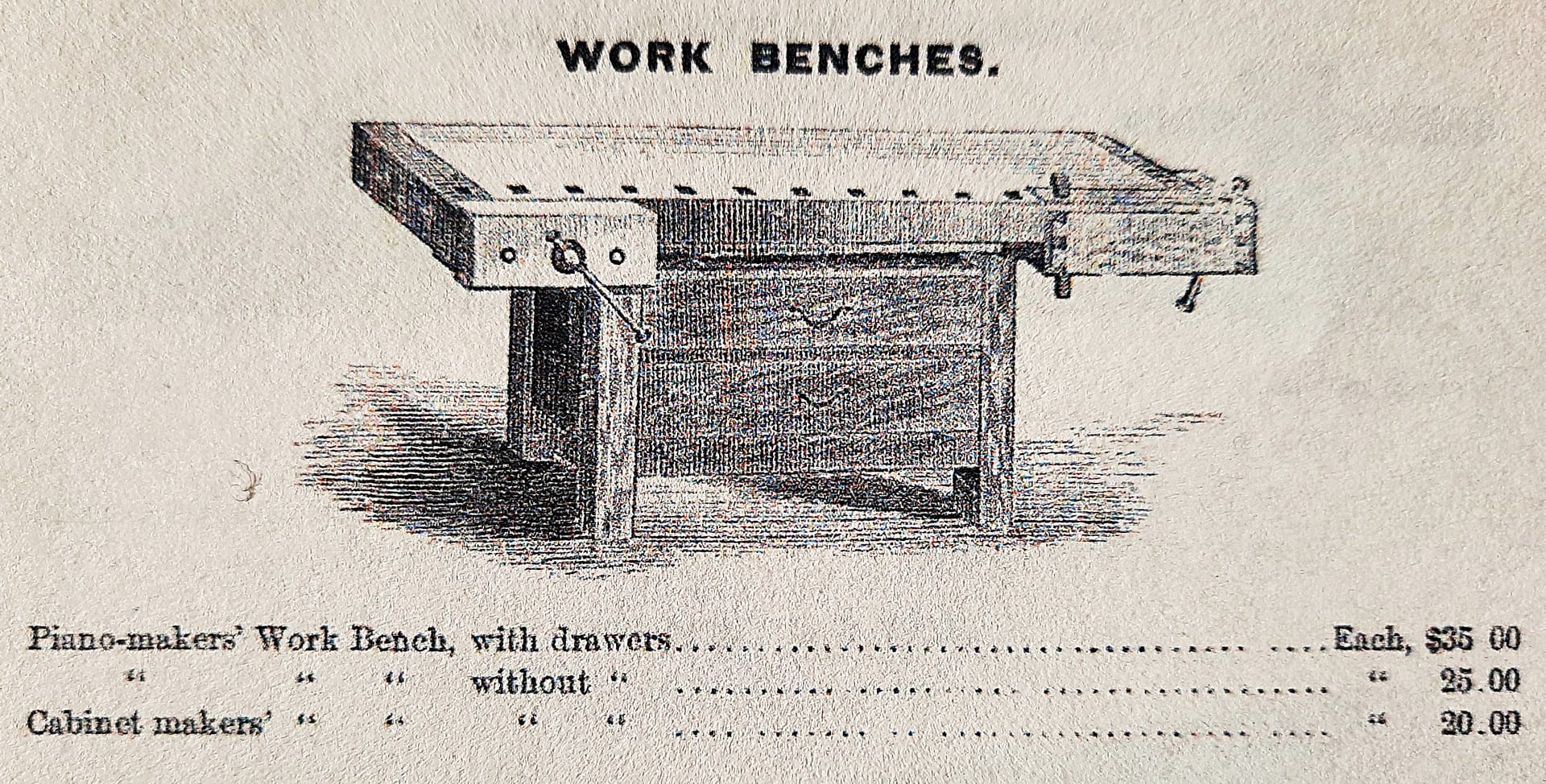

A beautiful mahogany workbench from the W.P. Emerson Piano Company, established in Boston in 1849. Photo from Martin Donnelly Auctions, 2021.

At the retirement of my informal business partner, his antique workbench, containing over three generations’ accumulation of piano tools, were simply passed on to me, and I am very grateful for that.

He told me, “You will never need to buy another tool.” I haven’t followed his advice.