© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

Erlandsen Rabbet Planes

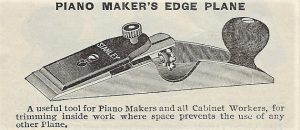

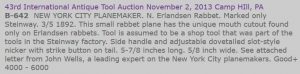

Steinway factory owned Erlandsen rabbet plane in the Nov. 2, 2013 Brown Auction. Marked Steinway, and probably a custom order, with a side handle and nicker, both of which are features not typical of the standard Erlandsen rabbet planes.

Both rabbet planes were likely made by N. Erlandsen. They share practically identical side escapements, the lack of a keeper or spacer for the wedge, and a 1/4″ thick sole. Pinned construction.

Very similar to the iron, steel, and rosewood version shown above. Construction is different, however, with the body done in two castings that are joined. The left side has 2/3rds of the body, and the right side has 1/3rd.

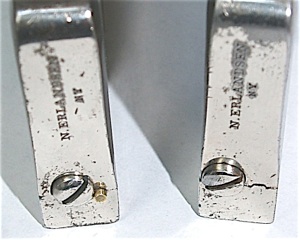

Three marked N. Erlandsen rabbet/shoulder planes, all with skewed cutters. All have side openings for the blade which has a combination rectangle and circle, a development borrowed from Brandt. A circle was to allow for better chip ejection curling up.

- On the left is a steel rabbet plane, early, with a later J. Erlandsen skewed cutter, possibly a replacement. Its body is made up of a number of applied steel components, i.e., sides, sole and center portions; the sides are pinned together, but require a loupe with proper lighting to detect. All together, its a heavy, solid steel tool.

- On the right are two early nickel plated cast iron shoulder planes. Napoleon Erlandsen was the first of the New York planemakers to introduce a rabbet plane where the body was wholly cast in one piece. Even with extensive hollowed out sections above the adjustable sole, and under the cutter, these planes are heavy for their size, much more so than the Popping shoulder planes shown later on this page. Casting these planes would have required cores, which involved some extra time and expense for Erlandsen’s production. A sliding adjustable front sole piece is locked by the two screws on top, and a fine adjustment is added at the front of the planes. Both of these adjustable planes belonged to one T. Larson, and you can see that the wear marks through the plating reveal a similar hand position on each.

- On the plane in the middle, just to the right of the fine adjustment screw is the end of an alignment rod which sits inside a half round groove on the top of the sole, and on the bottom front of the main casting. Erlandsen was borrowing directly from George Thorested’s adjustable iron rabbet and mitre planes here, so this plane probably dates from the 1860s. Later, Napoleon Erlandsen moved on to his own design for an adjustable sole, using a raised trapezoidal alignment rail as shown on the shoulder plane to the right.

Three Erlandsen rabbet/shoulder planes, c. 1863 to early 1880s.

Note the steeper angle of the rabbet plane’s wedge as compared with the lower angle wedge on the two shoulder planes. Traditionally, the rabbet plane was used with, or along the grain, and had the cutter set at a higher angle. Rabbet planes were intended to remover larger amounts of wood relatively quickly. Sometimes, as in the Erlandsen example above, they also had a skewed cutter.

Shoulder planes were used historically for end grain work and would have a lower angle for the iron, as well as a smaller mouth than the rabbet planes. With the New York planemakers, these distinctions became somewhat blurred, with both shoulder and rabbet planes having relatively low angle bevel up cutters and small mouths. Shoulder planes typically had straight blades, they were not skewed as in the two examples shown in the middle and the right. I have seen these types of Erlandsen tools described alternately as rabbet or shoulder planes.

Thorested-type alignment rod and Erlandsen’s raised trapezoidal rail. In order to make room for the trapezoidal rail, Erlandsen moved the fine adjustment screw to the extreme right.

Erlandsen’s complex rabbet planes had two hollow sections. The rectangular opening in the foreground leads to a void extending to the screw holes at the top of the plane. Expensive to produce, with a Patternmaker’s time and labor, involving the use of molds and cores.

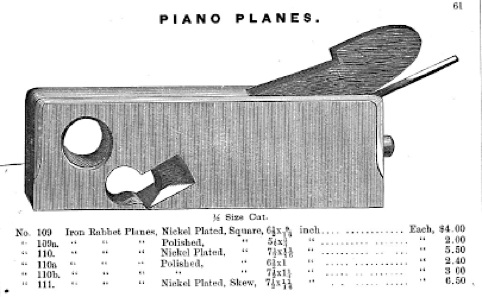

Erlandsen rabbet planes with fixed mouths, and available in six choices, as shown in the Jan. 1, 1885, Hammacher Schlemmer catalog shown below. This was a cast iron model with a finger hole to balance the weight as well as to give another way to help grasp the plane while working. It was surely a simpler way to lighten and balance the plane as compared to the extensive internal hollowing out done on the earlier cast iron rabbets. This 1885 catalog entry reveals that this model was introduced almost a decade earlier than what has been generally thought.

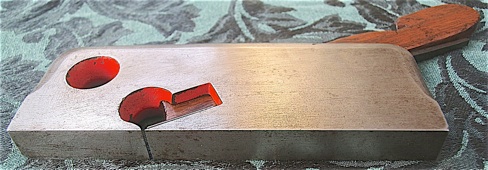

Erlandsen rabbet plane, with finger hole, fine fixed mouth, and original red paint. Another feature of this plane was the use of stanchions to support the iron, which were part of the single casting.

The hole in the front of the plane at the bottom is not painted red and appears to be machined, with a bevel around the perimeter. Other differences are the bottom one has a strike button and the body is nickel plated, while the one on the top does not have a strike button and is not plated. Both use cast stanchions to bed the irons.

It’s essentially similar in shape and size to the later and more known version with a hole through the nose, except that this one was cast in two pieces. The left side has 2/3rds of the body, leaving 1/3 on the right. No sign of pinning is visible, although the plane still has a fair amount of nickel plating left. As in the previous two rabbets, stanchions were used to bed the iron. This version did not have the red paint inside the escapement.

__________________________

Another early New York pianomakers rabbet plane, this one was made from flat brass stock, which was cut, shaped and brazed together, then screwed into the mahogany infill. Ward 1-1/4″ snecked iron and rosewood wedge. Coming from a working shop, the rear infill had a small removable shim added to make up for wood shrinkage, and the consequential lower bed angle as compared to the front portion of the blade.

JOSEPH POPPING

Joseph Popping’s work history

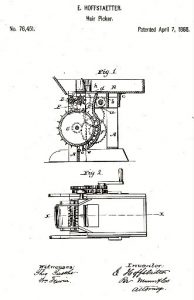

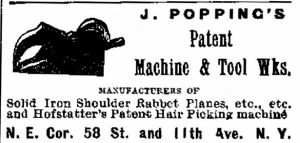

Joseph Popping was born April, 1842, in East Prussia. Popping’s output was primarily iron and bronze planes, mostly for the piano industry, and some of it through Hammacher Schlemmer. Outside of the piano industry, Popping produced Hofstaetter’s hair picking machine, and earlier in his career, gunsmithing work.

In 1869, Joseph Popping emigrated from Prussia to New York, married his wife Elizabeth Strunck (b.1850) on 6 October, 1872, and became a naturalized U.S. citizen on 17 August, 1874. Popping’s machine shop operations were established in 1873 and curtailed in late 1903 as shown by the New York City directories. His machine shop addresses were as follows: 55 West Broadway (1873–1874); No entries found for 1875–1879; 767 9th Ave. (1880–1881); 433 West 56th St. (1881–1883); N.E. Corner 11th Ave. x 58th St. (854 11th Ave.) 1884-1894>; 806 11th Ave. (<1897–1902). The 1900 US census revealed that Popping was still working, although “unemployed” for two months out of that year, so business was either slowing down or Popping took time off for personal or health reasons. Joseph and Elizabeth, his wife, rented their home. The 1905 New York state census showed that Joseph Popping, 63, was living “at home,” which in the terms of the census, meant that he was retired. Joseph Popping’s death certificate revealed that he died in Manhattan on November 27, 1906, at the age of 64.

Joseph Popping, machinist, in the “S.S. Herder” ship manifest, sailing from Germany to New York on 10 January 1878.

“Please send me Passport by early return mail as applicant will sail early on Thursday.” –J. Mones Public Notary, 91 Duane St., N.Y.C. Since there were no documents in New York City for Joseph Popping between 1875 and 1877, I would assume Popping was living back in Prussia for those years.

Popping 1897 listing, showed his 806 11th Ave. shop, c. <1897-1902. This was between W. 55th St. and W. 56th. St.

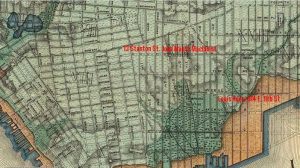

Joseph Popping, N.E. Corner 11th Ave. & 58th St. <1884-1894>; 806 11th Ave. <1897-1902. From G. Bromley, 1892 Map of Manhattan.

If you own a J. Popping plane, it was probably cast in one of the two iron foundries shown in this map.

Popping’s address in 1903, under variety stores (cigars), and semi-retired. This was in East Harlem (E. 123rd St), which had a large Jewish and Italian population at that time.

I did not find a Popping Machine shop listing in the 1882 Trow’s New York City Directory, so I would assume this is ‘our’ Joseph Popping.

Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of the State of New York …, Issue 11. 1897 Joseph Popping. 6 male workers; 58 hours of labor by minors in a week; 8 hours of total work on Saturday or Sunday.

Popping’s operation was as large as Erlandsen’s, and it was supported by piano workers’ demand for high production numbers of his shoulder planes.

Popping’s Patents

Joseph Popping, not known for originality or innovation in some circles, actually held at least four U.S. patents. The first two, dating September, 16th 1873, and December 9th, 1873, were both titled “Improvement in Welding Iron and Steel.” The texts of the two 1873 patents appear to describe traditional smithing techniques, with the introduction of some new substances, such as prussiate of potassia. On December 2nd, 1879, Joseph Popping obtained his third patent: Improvement in “Machines for Splitting and Shaving Willow Withes.” These were used for making baskets, which were more universal in the 19th century. The machine in this patent drawing looks complicated, and if any actual examples were made, it would have been a challenging project. Popping’s fourth patent for a washing machine was received on January 9th, 1894.

Popping Shoulder, Bullnose, and Mitre Planes

Three shoulder planes (named for planing the end grain on the shoulders, surrounding tenons), 1” width, and 3/4” width, by Joseph Popping, N.Y. Popping only marked the iron, never the plane body. This type of plane has the blade fully extending a scant 1/64” proud of the sides, which were made square to the sole. Most frequently found of all the New York pianomakers planes, but do not let a place like eBay deceive you into thinking that these are common.

Two Popping shoulder planes with steel faced gunmetal, and one Popping shoulder plane with nickel plating.

Joseph Popping was more productive as a planemaker when compared to Brandt, Thorested, or the Erlandsens. Julius Erlandsen, however, produced the largest volume of tools overall.

Popping shoulder planes were most often found in polished iron,

Popping shoulder planes, 1/32″ mouth, and 1/16th” mouth. Joseph Popping’s fit and finish reconsidered.

The 1 ” iron Popping shoulder plane example demonstrates that it was technologically possible to achieve a ~1/32″ fixed mouth on a production cast iron plane in the 19th century. And it also speaks to Joseph Popping’s capability in planemaking and in casting iron generally. I don’t believe that all of the Popping shoulder planes started out with such a fine mouth: many of these planes were used for much more than fine tuning joinery. They were used for a multitude of planing tasks, as evidenced by the relatively large number of these planes with blown out wedges, chipped mouths, and other signs of very heavy use. So, I would estimate that many throats on the Popping shoulder planes started out around at 3/32″ wide to accommodate the large range of work anticipated.

This was not the largest of the Popping shoulder planes. Dominic Micalizzi found a 1 1/2″ model in the early 1980s, but it was never shown in the catalogues.

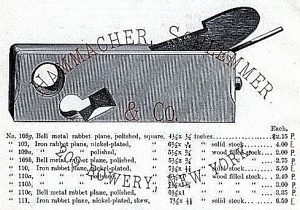

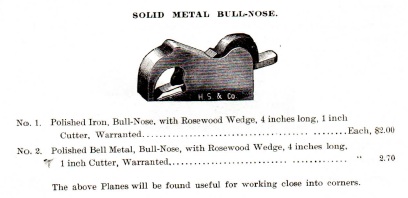

Hammacher Schlemmer pianomaker’s catalogue, 1891. Prices remained the same as the 1885 catalogue, and the Popping rabbet/shoulder planes were interspersed with the Erlandsen rabbets.

I have added a “P.” for Popping, and an “E.” for Erlandsen after the prices on this list. All of Joseph Popping’s shoulder planes were less expensive than the Erlandsen rabbets. Part of the reason for this was that the Popping shoulder plane was the only New York pianomakers’ plane where economy of scale lowered the price structure for the entire line. Another reason that Erlandsen rabbets were more expensive, was because the cachet of the Erlandsen brand meant that Erlandsen planes came at a premium. The three Erlandsen rabbet planes in this price list were nickel plated, and that added substantially to their cost. Popping’s steel-faced Bell Metal shoulder planes with rosewood infills however, had more expensive materials than any of the other planes in the price list, yet they were still less costly.

Joseph Popping. Early rabbet plane, rare version, with Stanley No. 113 lever cap screw. Rare, meaning perhaps two or three in existence. Photo from iluthier.com, c. 2005.

Another example of the Popping rabbet, rare version. From Bob Cotti’s collection.

Of all the New York Pianomakers’ planes. the Popping shoulder plane was closest in design and appearance to its counterparts: English shoulder planes.

But not this one!

Joseph Popping’s ad in “The Iron Age” 9 November, 1893, showing his bullnose plane. His shoulder planes are among the most repeatedly encountered of the New York hand planes so it makes sense that they were a specialty as advertised.

Hoffstaetter’s Patent Hair Picking machine was used to pick through and sort out horse hair used in 18th and 19th century upholstery. There is still a horsehair picking machine in the House of Representatives for periodic “refluffing” of the horsehair stuffing in the resident collection of antique furniture.

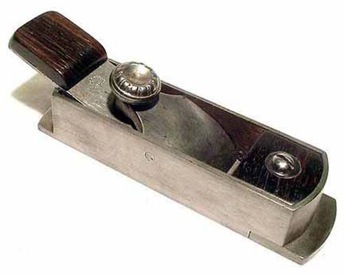

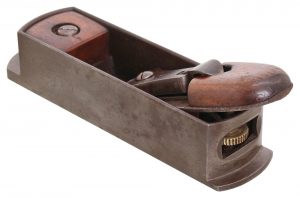

J. Popping bullnose planes, same casting pattern, but slightly different as a result of hand finishing. Gunmetal example is much heavier because the blade is bedded on solid bronze, which extends all the way to the sole.

J. Popping bullnose planes, H.S. Co. 1896 catalogue.

Popping made a fair amount of his bullnose planes, certainly more than his mitre planes, but nowhere near as many as his shoulder planes.

The Popping bullnose plane was introduced late (early 1890s), as far as New York Pianomakers’ planes are concerned. It may have been the last New York piano plane to have been produced in quantity.

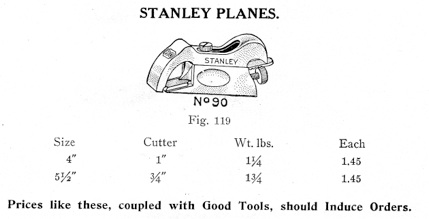

Three bullnose planes, all with one inch blades: Popping, with a fine mouth and a large boxwood wedge, which is larger than I’ve seen on other Popping bullnose planes, which are typically rosewood. Perhaps Joseph Popping was just taking advantage of a good sized, unflawed piece of boxwood. Other Popping bullnose planes I’ve seen also have side openings with a small convex curve at the rear portion; the Popping shoulder planes shown earlier, have a convex curve with a larger radius at the rear of the side openings. Also, the rear ‘ears’ on the Popping do not extend behind the sole, like they typically do, as on the Preston bullnose in the back of the photo. The Preston is one of a general type which served as an example for Stanley, Popping, and Williams & Ham, of Troy, NY. Middle plane is a Stanley #90 from the 1920s ‘sweetheart’ era.

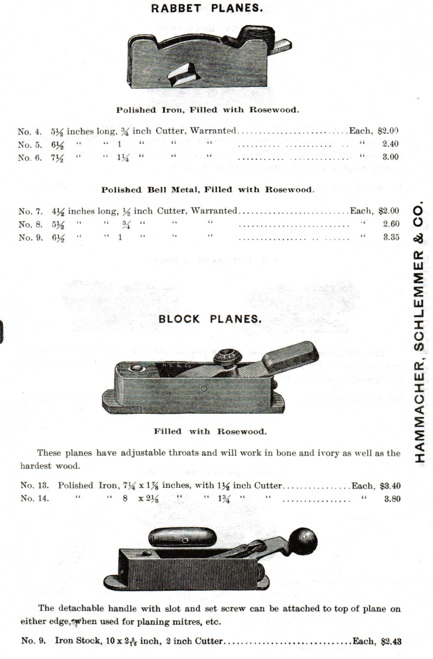

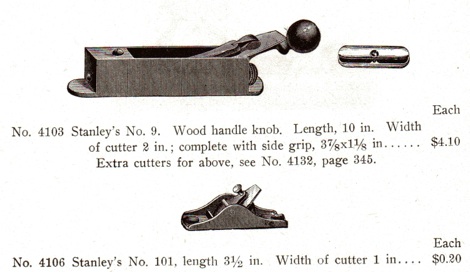

From Hammacher Schlemmer 1896 catalogue. J. Popping shoulder/rabbet and mitre planes, as well as Stanley/Bailey cabinet maker’s block plane.

At $3.80, the No. 14 Popping mitre was a lot more expensive than $2.43 for the No. 9 in 1896 money, but less than the $4.50 for the equivalent Erlandsen mitre, No. 113A in the 1891 H.S. catalogue. Later on, in the Hammacher Schlemmer pianomaker’s catalogues for 1896 and 1903, prices on Erlandsen’s unplated polished steel mitre planes were lowered: 113A, 8″ with 1 3/4″ iron was reduced to $3.60, and 112A, 7″ with 1 1/2″ iron was reduced to $3.25. Prices for the plated Erlandsen mitres remained the same between late 1884 and 1903. H.S. catalogue:

[Popping mitre] planes have adjustable throats and will work in bone and ivory as well as the hardest wood.

On Popping mitre planes, the throat was easier to adjust than either Brandt’s, Thorested’s, or Erlandsen’s mitre planes.

Three adjustable front sole pieces: left- Stanley No. 9, with top screw head and washer sitting on elongated hole in top of plane body and threaded into front sole–with fine adjustment screw in front; middle- Erlandsen, attached to body with three adjustment screws with heads over slightly oblong holes in upper sole, and threaded into lower sliding front sole piece.; right- Popping, with sliding bolt in cage.

The throat was made to be adjusted by a single screw at the top of the infill, as compared to most all the other New York mitres where removing the infill and adjusting two or three screws on the upper front sole was necessary. Popping’s mitre had the top adjustment screw threaded into a large nut held inside a captive cage where the nut could slide forward and back. Bailey’s top adjustment for the mouth, introduced with the Bailey mitre plane in the early 1860s, provided the example for Popping, who designed his mitre plane with top adjustment around 1872.

Joseph Popping bought his lever cap screws for these mitre planes from Leonard Bailey (1825-1905), whose patents were bought by Stanley Rule and Level Co. Bailey lever cap screws, made for the Victor line of planes, would have been in production between 1875 and 1888. Popping probably bought enough Bailey screw inventory to continue making mitre planes into the 1890s. Production of Popping mitres, however, was minuscule when compared to the very popular Popping shoulder planes, because his mitres were never big sellers. The piano industry, large as it was in the late 19th century, consisted of a specialized, confined market, and the Popping mitre was competing with the less expensive Bailey/Stanley No. 9 cabinet makers block plane, as well as the upmarket nickel plated Erlandsen mitre. For those piano workers on a restrictive budget, temporarily making-do with the larger block planes, such as the Stanley no. 19, became an option. At least until an upgrade became affordably within reach.

Shoulder planes made by Popping, however, with the true shoulder plane profile and hand holds for challenging joinery, really had no competitor in the United States, except for the more expensive British imports. –Stanley shoulder planes, Nos. 92, 93, and 94, were introduced in 1902, when Joseph Popping was in the process of winding his operation down, and retiring.

Stanley provided lever cap screws for the earliest Popping mitres, roughly between 1873, Popping’s initial establishment in NYC, and 1875, when Bailey’s Victor lever cap screw became available.

Lever cap screw from Stanley No. 113 compass or circular plane, used on early J. Popping mitre planes, from approximately 1873 to 1875.

Popping mitre that sold on ebay in September 2017 for $1,375.00. + shipping. Small mouth chips and infill wood damage.

Joseph Popping mitre plane, 7 1/4″ sole, 1 1/2″ iron, 1/7/8″ wide (H.S. No. 13). Photo iluthier.com c 2005.

Popping mitre plane with a Bailey Victor lever cap screw, which was in production from 1875 to 1888. In Hammacher Schlemmer’s 1896 Tool Catalogue, the line of Popping mitres was still available, and pictured with the Bailey Victor lever cap screw, so Joseph Popping undoubtedly bought a large supply of these proprietary thumbscrews from Leonard Bailey in around 1888.

Example in front is marked with the fitting number 77 in three places: iron, front sole piece or toe, and the body casting. These planes are similar, with the differences primarily in the woodwork. Front infill of the plane in the foreground has the grain running side to side, and plane in the rear has the grain running front to back. And that infill is slightly longer. Also, the pads are shaped differently, with a cutout for the lever cap neck and screw on the Popping shown in the back.

Erlandsen’s role as piano tool and machinery supplier to the industry:

Napoleon Erlandsen advertisement for Models and Experimental work, in the “Scientific American” May 11, 1889. 107 Rivington St.

Popping had Hofstaetter’s hair picking machine, George Thorested had Nystrom’s calculator, and Lauritz Brandt had the Bruce typecasting machine. But the Erlandsen’s had their particular niche within the piano industry dominated with a wide offering of hand tools and machinery for pianomaking, supplying Hammacher Schlemmer, Schley, Alfred Dolge, American Felt Co. , and others, as well as their own modest proprietary offerings. Beyond the U.S., J.& J. Goddard in London, and Otto Higel in Toronto, Canada, also offered some Erlandsen tools. Erlandsen’s also provided machine tooling work for models and prototypes which they advertised in the “Scientific American.”

A lineup of New York mitre planes. 1. to r.: Erlandsen; Brandt; Brandt; Thorested; 4″ bevel down mini-smoother. James Claussen collection.

Even though Thorested and Brandt have held special interest for collectors seeking rare tools, it was the Erlandsens who truly left their mark on the piano industry. The bulk of Brandt’s tool production was between 1842 and 1860, with any subsequent output unsubstantiated. Thorested made his last planes in 1858. To put this in perspective, Steinway & Sons in New York was established in 1853. Chickering of Boston was the leading pianomaker in the U.S. from the 1840s to around 1870, when Steinway superseded Chickering as the leading piano company.

Based on the number of tools that have been found, Julius Erlandsen’s output appears to have been predominantly specialized piano tools, while more planes and bow drills with Napoleon’s mark seem to have survived. Concurrent market demands during the span of the Erlandsen’s output (1863–c1940) are in line with the numbers of various extant Erlandsen tools.

While the relatively small output of Thorested and Brandt did not have the impact or influence on the piano industry when compared to the much larger and broader output of the Erlandsens, the study of these makers uncovered the development of the New York pianomakers planes. And without question, Napoleon and Julius Erlandsen were influenced by Brandt and Thorested, as it can be seen in the design aspects of their planes and bow drills.

Here is a specific example of Brandt’s and Thorested’s influence on N. Erlandsen. Photo from Jim Bode.

This small 7 1/4″ N. Erlandsen mitre plane has a brass plate at the back of the front infill, instead of the typical convex rosewood moulding. The brass plate was introduced by Brandt in his later planes, and used by Thorested as well. It made shaping and fitting the infill easier, and in the case of the Erlandsen mitres, gave more space to the escapement, which has less room than other N.Y. mitres because of his convex moulding. This relatively narrow escapement is found in the smaller Erlandsen mitres such as H.S. no. 113A shown earlier on this page.

Lauritz Brandt and George Thorested sought to find more efficient means of production throughout their working careers. Brandt succeeded in attaining mass production with his Danish factory producing the Bruce Typecasting Machine, but not with his tool making business. Nevertheless, the early ideas of Brandt, such as the adjustable mouth, and brass plate in the rebate of the front infill, and George Thorested’s introduction of casting planes in iron laid the groundwork for later makers. These early ideas were developed with the intention of making it possible to increase production while still maintaining the quality of their tools.

Because these early innovations enabled greater efficiency, Napoleon Erlandsen was able to achieve a higher level of production than either Brandt or Thorested. But true mass production within this small group of piano tool makers, albeit on a relatively modest scale, was only achieved by Joseph Popping with his shoulder planes, and, by Julius Erlandsen, with his mass production of specialized piano tools in the late 19th, early 20th centuries.

Knorr & Mantz

Knorr & Mantz mitre plane. Interesting use of variegated rosewood with sapwood. Norris also used variegated rosewood in a few of their infill planes over the years. Ornate lever cap screw with cusp, probably a Spiers influence. Photo from Jim Bode tools.

I did not find a “Knorr & Mantz,” but I did find two individuals in the right trades within close proximity on the Lower East Side. From Trow’s N.Y.C. directory, for 1870.

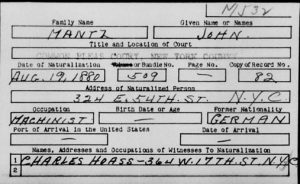

1870 U.S. census for John Mantz. While N.Y.C. city directories from the 1870s to the early 1890s list Mantz as either “machinist” or “engineer,” (some at the same E. 54th St. address) this John Mantz was working in a Carpenter’s shop in 1870.

Naturalization card for John Mantz. As a machinist and German immigrant, he fits the profile for a New York maker of planes for the piano industry.

Detail of map from Sanitary & Topographical Map of the City and Island of New York. Viele, Egbert L. 1865. Locations of 1870 addresses of Louis Knorr & John Mantz on the lower East Side.

Lever cap is remarkably similar to Erlandsen’s lever caps: in overall shape as well as the inverted cone underneath the neck. Even the lever cap screw is interchangeable with Erlandsen’s, and has the same threading. With the influence of Erlandsen, the time frame of c. 1870 for this plane is confirmed. Front and rear infill made of solid rosewood. Adjustable front sole piece unusually thick and heavy.

The front infill is neatly marked “H. Meyer,” which may have either been an owner’s mark, or a dealer’s mark, as one Henry Meyer was a partner in “Meyer & Eiffler.”

INNOVATIVE NYC STYLE MITRE PLANES:

NY style (looks like cast iron) mitre plane with interesting infill and lever cap. Maker unknown, but similar to Buchhop plane shown below.. Photo from Donnelly auctions 2015.

From Martin Donnelly auctions, April 2016.

This plane is nicely appointed with a brass locking screw for the cap and a rounded brass washer to secure the throat adjustment. It retains its full cutting iron by Shepherd Brothers and and is in excellent collector quality condition. Henry Buchhop was listed as a cabinetmaker in the 1867 New York City Directory, living at 133 Sixth Avenue. In 1872, he was listed at 147 Avenue A. In 1878 he had moved to 458 W. 50th Street, where he worked as a cabinetmaker. He worked as a cabinetmaker in New York City throughout his life. The plane is marked with the designation “H. Buchhop” on the bridge. Its unique configuration suggests that Buchhop may have made it himself.

New York mitre plane with adjustable blade angle and Bailey type lever cap. Martin Donnelly Sept. 2017 auction.

Mitre/Rabbet plane. New York style design, with adjustable mouth. English badger/rabbet/mitre planes exist, but this example may be a one-off. Photo from Ebay, December 2017.

New York mitre, unmarked. Dovetailed. Possibly made by L. Brandt or a contemporary maker. Photo by Paul Blanche, Ebay, 2015.

Here’s my succinct research: Buchhop was born in Germany in 1824; arrived in N,Y. August 16th, 1850; was naturalized June 1, 1857; died January 23, 1900 in Brooklyn.

L. Brandt mitre plane (unmarked), with external front adjustment for mouth. Detail of adjuster. Photo from Bob Cotti.

L. Brandt mitre plane (unmarked), with external front adjustment for mouth. Detail of toe. Photo from Bob Cotti.

If Lauritz Brandt made this plane, it showed that he was involved in developing an adjustable iron back in the 1850s.

Miniature New York style mitre plane marked Tollner (1851-1861). 3 5/16″ long, with 15/16″ iron. Dovetailed construction. Some debate exists regarding who made this plane, an early effort by N. Erlandsen being John Wells’ assertion. From estate of John G. Wells. Photo by Jim Bode.

There were at least two ways to make it easier to make the iron extra tight and secure. One was to increase the distance from the lever cap pin to the thumbscrew, and the other was to simply make the thumbscrew larger. Both approaches were ways to gain more leverage.

Some more Stanley planes used in the piano industry:

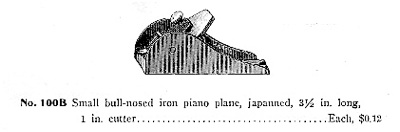

Stanley finger planes, numbers 100 and 101.

Stanley finger plane No. 101, made from 1877 to 1962. This very small plane was included in most of the piano supply catalogs between 1885 and 1940, because it was small, useful for a number of repairs, and could easily fit into a mobile tuner’s kit. These detail planes were used to remove wood in situations where today, sanding or filing would be more commonplace. This Stanley 100 with the squirrel tail tote was made in the 1930s, and the #101 in the foreground has the early Stanley inscription, which would date it to 1877–1884.

Improved versions of these planes are currently made by Lie Nielsen and St. James Bay, and various other copies are offered in recent piano supply catalogs. I have used small planes such as these for jobs on basswood keysets in 1950s-1970s U.S. spinets and consoles where the keys were so badly warped that no amount of spacing at the front of the key would give clearance at the back of the keys. In other words, the keys actually were rubbing against an adjacent key. In a situation like this, one of these planes with a properly sharpened blade, did a much neater and cleaner job of slightly narrowing the rear sides of the offending keys than either filing or sanding.

Stanley bullnose plane. This plane never appeared in the Stanley catalogues, but was featured in my 1903 and 1919 H. S. catalogues. Its a rare plane, based on the No.101.

American Felt Co., 1911.

Two Stanley planes, Nos. 9 and 101. The No. 9, Cabinetmaker’s block plane, was made from 1870 to 1943. This was Stanley’s version of the Erlandsen mitre plane as well as the English infill mitre planes, and this model was also used in the piano industry. A No. 9 was among the planes found in Studley’s tool chest and It included the added adjustment features which were standard in Stanley planes. Stanley No. 9’s are avidly sought by collectors–modern copies of this plane were made by Lie-Nielsen until 2013. American Felt Co.,1911, although the pictured #9 is a earlier version. An even earlier version, the Bailey No. 9, can be seen here:

Bullnose plane 1″ X 4″, c. 1905, Schley piano catalog. This plane could be separated at the seam in the middle and the bottom portion could be used as a chisel plane.

“Prices like these, coupled with Good Tools, should Induce Orders.”

Was Schley writing for their potential customers or for themselves?

This plane was intended for the piano industry, as well as for cabinet makers. Number 97 was used to clean up interior surfaces right up to the edges, like a chisel, but with the added support of the sole combined with a fixed blade angle. It was also good for cleaning up glue lines and doing trimming (a protruding dowel, for example) without harming an existing finish.

Stanley #97 chisel plane.

Antique chisel plane, user made razee style: mahogany body, oak tote, with brass sole and Sorby iron.

Three dovetailed steel English box mitre planes:

Three dovetailed steel English box mitre planes, generally these designs served as examples which influenced Bailey and Erlandsen. All three planes have fine non-adjustable mouths, especially the Moseley and the Spiers. On average, these English planes have smaller throats than either the Stanley No. 9 or the New York piano planes when adjusted to their narrowest aperture. There are notable exceptions, however.

- An early mitre, c. 1800-1830, heavily constructed, with a 2″ blade, beech infill and rosewood wedge, 2-3/8″ wide by just under 10” in length. The blade and wedge were replaced, probably in the 1870s, because the Cloverleaf blade, from Albany, NY, dates from that time. Its conceivable that this plane could have been used for piano work, as it has likely been in the U.S. for much of the 19th century, and there were a limited number of applications in cabinet work and related applications then, and piano work was one of them.

- Middle plane is a Moseley and Sons, London, c. 1820–1840, with the same dimensions as the the early mitre, and a 2″ cutter (Ibbotson) as well. The infill is rosewood, and the bridge constraining the wedge has a cupid’s bow design. . This one looks very similar to other Towell mitres, and probably was made by Towell.

- Large mitre on the right is an unsigned Spiers (Stuart Spiers 1820-1899 Ayr, Scotland), 2-3/4″ wide by 10-3/4″ long, with a 2-1/4″ Ward iron. This one differs from the other two in that it has a lever cap for the iron, instead of a wedge, to make blade adjustments easier. The Ward iron is snecked; the added fitting at the end of the blade allowing for tapping the blade back as necessary as well as providing another place for the hand to push this rather large heavy plane.

Miniature coffin-smoothing planes

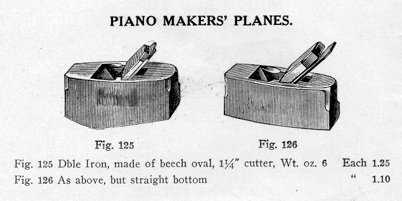

Miniature coffin-smoothing planes: the one on the left has a compassed sole, and the one on the right has a flat sole. From Schley 1905 Catalogue.

These are very small planes, about 3-1/2 to 5-1/2 inches in length, usually with a 1-1/4-inch cutter, and they have also been used for model making. Diminutive coffin planes, like the full range of wooden bodied planes, became less used by the turn of the 20th century, and were not made in any significant quantity after the 1920s.

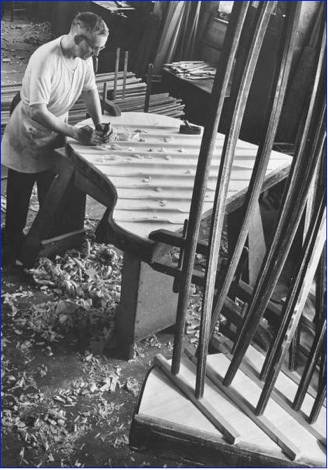

Bourke-White photograph of a Steinway bellyman at work.

This is a 1935 photo by Margaret Bourke White showing a worker in the Steinway factory planing the concave taper at the ends of the soundboard ribs. You can also see go-bars clamping down the ribs to the soundboard—the soundboard is likely one of the early diaphragmatic design types—the patent was applied for then. This worker looks to be using a compassed miniature coffin smoother, like the one in Fig. 125.

The rosewood plane (l.), with a steel sole and a double iron was user made. The plane in the upper right has a strongly compassed, or convex, bottom.

Veneer scrapers and spokeshaves:

Scrapers from the veneer department of an early 20th century Boston piano factory.

These tools belonged to a Swedish cabinet maker who worked in the veneer department of a Boston piano factory in the early 1900s to the late 1920s. He dated many of his tools, and the Stanley #12 veneer scraper is stamped 1907 on the handle. These two mahogany ram’s horn scraper shaves were user made, probably by himself, and very well executed. His blades were made from an old saw, and the sole and blade holder of the one in the foreground was cut from bone, looking similar to ivory, making this a beautiful tool. Fine scraping was an older, standard method for creating a smooth surface on veneer, instead of sanding, which left the wood pores more open and free of sawdust, as well as being easier on the lungs. Veneer was a good 1/16″ thick then; most new pianos today have thinner, even paper-thin veneer coated with a thick layer of polyester resin.

This Swedish immigrant craftsman made hide glue brushes, presumably for attaching veneer to piano cases, out of the inner bark of basswood. Here is a description of this unique brush making process.

From A. Reblitz, “Piano Servicing, Tuning, and Rebuilding.”

Andrew J. Boisvert (March 22, 1917- April 22, 1991) using a spokeshave for final shaping/fitting of a pinblock to the plate flange in a new Knabe grand. This was in the Aeolian American factory in Rochester, N.Y. during the mid-1970s. Spokeshaves have an angled cutter like a plane, rather than set at 90 degrees with the edge curled over as in the scrapers seen above. Close at hand is a chisel and a bit brace, which are also used in this procedure.