Norris No. 10 box mitre planes (and related types)

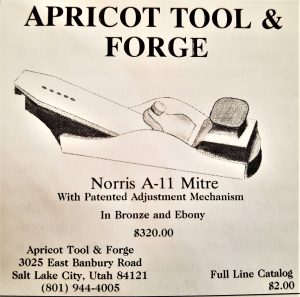

…It is particularly satisfying to note that this particular tool [a Norris A11 Mitre plane], Norris’ last gasp in this genre, fittingly, was destined to be used as a pianomaker’s plane; precisely the same traditional function as that described by Bailey for his Stanley no. 9, the original adjustable block mitre plane.

–Maurice Fraser, “Fine Woodworking” June, 1990 Taunton Press.

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

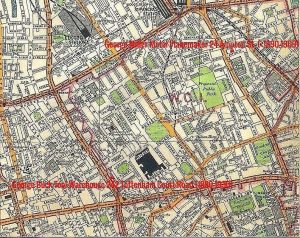

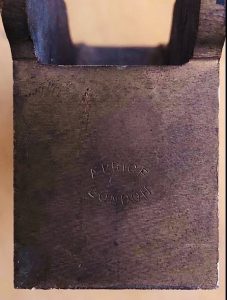

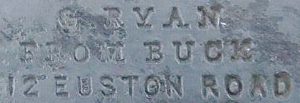

Holland mitre plane (Buck), 247 Tottenham Court Road, with strong convex curve on bridge, closest to that associated with Norris.

Norris no 10 mitre plane (Buck), with a 1 3/4″ Mathieson iron, which contributes to unveiling the working relationship between Norris and Mathieson. Note the tapering wedge in the Buck/Norris No. 10 (narrower width at scroll).

Norris No. 10 mitre plane, showing 3 dovetails on the side: 1 dovetail in front of the mouth, 2 dovetails in back of the mouth. Photo by Robert Leach, 2015.

The Norris No. 10, 10″ mitre shown on the right, reveals 3 dovetails on the side, which are usually almost impossible to see because Norris used steel for both the sole as well as the sides. In no way does Norris’ diminished number of dovetails on their mitres reflect on the overall highest quality of these planes. But the Norris mitre construction does provide another key differentiation when compared with the Holland/Buck type of mitre plane, which typically has 2 dovetails in front of the mouth, and 3 dovetails behind the mouth.

Direct sunlight reveals interlocking grain which otherwise appears as a reddish black. Infill of a Norris No. 10 mitre plane.

- Both 10s have cosmetic diagonal cuts at the front corners–a Norris ‘tell’ for this model.

- Holland and 10/lever cap have similar front flange.

- Holland and 10/wedge both have tapering wedges widthwise (narrower at scroll).

- Both 10s have a clean heel with no strike button or screw. (247 and 242 Buck/Holland mitres similar)

- 10/lever cap. Short but heavy lever cap similar to that on Norris 11 improved and A11 mitre planes.

- Holland and 10/wedge have similarities in design of bridges.

- Both 10s have Mathieson irons.

Norris No. 10 mitre plane, with wedge and bridge, 9 inches long. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, September, 2017.

Norris no. 10 mitre plane, 9 1/8″ long. Formerly No. 1271 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell. Photo from Ebay UK, circa 2015.

This large Norris No. 10 mitre plane was probably one of the last No. 10s made, as it has an iron with the NORRIS LONDON stamp with serifs, c. 1913 to 1943. This plane likely dates to 1913-1914. There are a few Norris planes which are older than 1913, and still have this type of stamp on the iron, but the iron may not be original to the plane. I have not seen another Norris No. 10 with this stamp on the iron. Other examples of the No. 10 have Ward, Sorby, Mathieson, or unmarked irons.

.

The Norris No. 10 mitre plane shown below sold for $9,500.

Norris No. 10 Mitre plane, 6 1/2″ long, with a 1 7/8″ Ward iron. No. 1272 in David Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools”; Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, September, 2013.

This small mitre plane has a long early lever cap with cusped thumb screw and early Norris stamp, which appears almost oversized in proportion to the body of the plane. Short front and rear flanges hold the overall length of this plane to just 6 1/2 inches.

Norris and Spiers filed off and cleaned up the screw holding in the rear infill when making their mitre planes. This contrasted with the many earlier mitres found in the field which had a cheesehead screw sheared off from excessive hammer blows, and did not leave a clean appearance.

It has been stated that Norris was an average or unremarkable maker of infill planes until Thomas Norris Jr. decided to take the business upscale with the Norris Patented Adjuster in 1913. While it is true that Norris made a number of cast smooth planes (and others) in the late 1880s through WWI, they also made some fine dovetailed planes early on. Norris’ no. 10 mitre was an example of this first rate quality. Early dovetailed models, such as the panel, smoother, shoulder, and rebate–nos. 1 through 9–were included in the 1908 catalogue. The quality on the above planes was as high as that of any period of Norris’ plane production.

Sometime after the publication of the Norris 1908 catalogue, and before the 1914 catalogue, the number 10 mitre was retired. Norris continued to make a limited number of small box mitre planes after this time frame stamped with the number 11, sharing that number with their improved pattern mitre plane.

Norris No. 11 mitre plane, 5 3/8″ long, 1 3/4″ wide, a diminutive form. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, March, 2013.

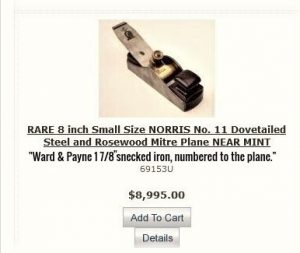

Another Norris no. 11 miniature box mitre, 5 3/8″ long, with a 1 1/4″ iron. $10,995.00. Sold. Photo from Jim Bode Tools.

Norris No. 11 Miniature Mitre Plane as it appeared as #1277 in David Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools,” 2010. Photo from Norrisplanes.com

This photo has a strange shadow on the bridge, which changed the appearance of the bridge and the Norris stamp, but it is indeed the same plane as the one included in David Stanley’s March 2013 auction.

Dovetails are visible on the front corners of this plane.

On 23 March 2013, the exchange rate was 1.58 USD to the GBP, so the estimate ranged from approximately $11,600 to $15,800. In actuality, 1017 sold for £6,500, which was $10,270, not including the buyer’s premium of 15% ($11,810.).

At 5 3/8″ length with a 1 1/4″ iron, the miniature box mitre had the same dimensions as the Norris nos. 31 and 32 Thumb planes. A notable difference between the box 11 and the Thumb planes was that the no. 11 mitres were constructed with a separate two piece sole, and some dovetailing, while the thumb planes were cast malleable iron or gunmetal.

The No. 11 is marked with 2 on the iron, wedge, and infill bed.

Gunmetal versions of the Norris Thumb plane had a steel face, which was sweated onto the casting, The sole was applied in two pieces, front and back, in order to control the size of the mouth, and to provide a most durable working surface.

A range of Norris box mitre planes. In comparison, you can see just how massive the large No. 10 is. The Norris No. 11 was formerly in the pre-1908 price list as a 5″ No. 10. The Norris miniature No. 11, circa 1920 differs from the No. 10s in the following (non-essential) ways:

- Bridge reversed, with cupid’s bow in front.

- Heel has cheesehead screw/strike button.

- No cosmetic diagonal cuts in the corners at the toe.

Generally, all of the irons in the above Norris box mitre planes have narrower sized irons relative to the width of their respective plane bodies, and have extra room on either side of the throat when compared to mitre planes made by other makers. This allowed more space for adjusting the irons as well as being more forgiving towards a cutting edge that was not perfectly square to the sides of the iron. All the irons in the Norris box mitre planes are parallel, with the exception of the Mathieson iron in the 8″ mitre plane shown in middle of the line-up, which is a tapered iron. This nibbed Mathieson iron is original and numbered to the plane and wedge, with a “0.” This plane is probably the oldest example in the the photo of 5 planes, dating from the 1880s or 1890s.

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

Norris No. 11 Improved pattern mitre planes

The 1892 drawing of the Norris No. 11 Improved mitre plane was very similar to the image in the 1908 and 1914 catalogues. Perhaps the very first Norris Improved mitre planes had the rebate around the front tote. For a small outfit like Norris (and other similar small British planemakers) updating the picture for subsequent catalogues may have been seen as an unnecessary expense.

In 1892, smaller Improved mitre planes did not have to be special ordered. This was also the case with small Melhuish/Norris smooth planes then.

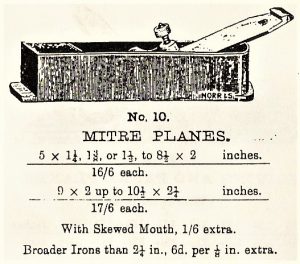

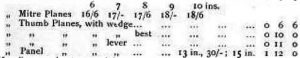

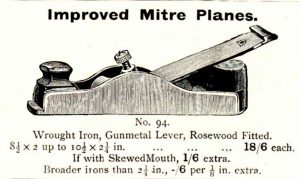

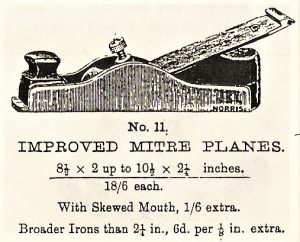

Norris No.11/ Mathieson No. 847 Improved Mitre plane. 1899 Mathieson Catalogue. Later front infill without rebate on sides.

In the 1899 Mathieson Catalogue, the woodworker could order a mitre plane, either improved or box, as short as 8 1/2″ or as long as 10 1/2″, with an iron 2 1/4″, 2 3/8″, or 2 1/2″ wide. Impressive choice and selection in the early catalogues.

Presented below is a Mathieson Improved Mitre plane that was bought in from Norris, in around 1910 to 1915. The finial on the lever cap screw and the cello-shaped rear infill, as well as the “STEEL” stamp date it to this period. Mathieson marked this mitre plane in three places: on the rosewood front infill, on the lever cap, and on the cutting iron. Norris made the plane, and Mathieson made the nibbed iron for it.

“STEEL” stamps on Mathieson (Norris) planes: left, STEEL with serifs c. ~1899-1905; middle, STEEL in plain letters c. ~1905-1910; right, STEEL in italicized letters c. ~1910-1940.

The 8 1/2″ size was still included in the Norris c. 1908 catalogue. Similar, but not identical drawing of the same plane as depicted in the 1892 and 1899 Melhuish catalogues.

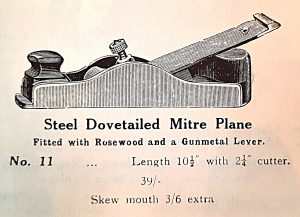

Price for the standard model (10 1/2 inches long) 1914 was 19/6; Price for same in 1928 was 39. The No. 11 Improved mitre was not included in the 1938 Buck & Ryan catalogue. This drawing still shows a front tote, surrounded by a rebate, in the style of Spiers. Most Norris no. 11’s did not have this rebate, as shown in the following photos.

In general, when a catalogue item was not sold in large numbers, there was a greater likelihood that the drawing would not be updated. This was the case with Spiers’ catalogues as well. Norris’ No. 11 Mitre plane was never a big seller; fortunately for posterity, this did not discourage Norris from carrying low volume products for many years.

Overall, the sides of the Norris improved mitre are slightly higher or deeper than those on the Spiers improved mitre plane, and the front tote stands about 1/2 inch taller on the Norris version as opposed to the Spiers.

This image provides a good overview of some of the differences between the Norris Improved Mitre plane and the Spiers improved mitre plane. The chamfers on the steel sides taper almost to the crests of the cheeks, while the Spiers are chamfered only at the infills. The rear infill is completely flat at the top, in contrast to the Spiers, which has rounded edges around the perimeter. The rear section of the front infill (forward of the mouth) is a straight but angled cut, whereas the Spiers has an ogee moulding in front of the mouth. The short lever cap, although associated with Norris, was actually introduced by Spiers, as early as the 1870s, as shown on this page. Other differences are more obvious, such as the classic Norris cusped lever cap screw.

Heel of early Norris No. 11 Improved mitre plane, showing flat-topped rear infill. Photo from Norris,planes.com

The improved mitre on the left is the earliest in this group of photos, with the cello-like rear infill, circa 1890 – 1914. On the right is the short model with the front infill covering the flange, and it is somewhat later, having a rear infill without the indentations or finger holds. It still retains the cusp on the lever cap screw, so probably dates from the World War One era.

Norris No.11 Improved mitre plane, 8 inch model. Daniel Worsley iron. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, September, 2016 (Lot 938).

The skewed improved mitre plane on the lower left is one of six that I am aware of (there probably are more), and it was owned by Max Ott, which comes as no surprise. It also dates from the World War One era. The no. 11 improved mitre plane on the right is the latest example in this grouping with 1. a standard diamond pattern knurling on the lever cap screw (rather than the earlier proprietary pattern in rows); 2. the lever cap showing a slightly more cushioned look, with a more gradual rise at the neck; 3. a slight chamfer on the body at the toe; 4. continuation of the rear infill without indentations. 5. Larger NORRIS LONDON stamp on lever cap, with model no. (11) in between. I would estimate that this plane dates from the mid 1930s, and was probably one of the last improved mitre planes made, until the Henley Optical Company resurrected the form in the mid-1970s.

Norris No. 11 Improved mitre plane, with standard cross hatch/diamond pattern knurling on lever cap screw. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, March, 2016.

Norris No. 11 Improved mitre plane, skewed cutter. Ex Max Ott collection. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, September, 2015.

Norris Skewed No. 11 Improved Mitre Plane, as it appeared in the David Stanley International Auction 26 September, 2015.

The holy grail for some; pure folly for others. And the full spectrum in between.

The high price of Norris mitre planes is reflection not only of the company’s exceptionally low output, but of the prestige of the Norris name itself. This prestige is compounded by the fact that in the later years, public awareness of its rivals’ names had dimmed, The Norris Co. almost alone among them, survived the 1930s Depression and was even exhumed, briefly, after World War II. To postwar craftsmen, then, the varied line of Norris planes, even the somewhat debased, “austerity years” versions from the late 1940s, remained the tools of choice. Norris, thus, finally advanced beyond being merely first among equals: the company became the “Last of the Mohicans.”

–Maurice Fraser, Fine Woodworking, Taunton Press, 1990

This Norris No. 11 Improved mitre plane is another late example, but probably not as late as the one pictured in the David Stanley March 2016 auction shown above, as it has the earlier Norris knurling pattern on the lever cap screw. Other features are similar to this mitre plane.

Some Custom Ordered Norris No. 11 Mitre Planes:

Oversized Mathieson Skewed mitre plane. From the excellent comprehensive collection of George Anderson.

This oversized Mathieson Improved mitre plane was most likely bought in from Norris. George Anderson called this a plane for Paul Bunyan!

Norris No. A11 adjustable mitre plane, a custom order in the Improved pattern. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auctions, October,2021.

With an exaggerated ‘boat stern’ heel, the overall look of this improved mitre plane was changed. It was made in the 1930s. Planemaker Karl Holtey referenced this custom order Improved A11 in the webpage on his own No. 11 mitre planes:

[The Norris No. 11 Improved Mitre] plane was never intended to be made with an adjuster and I have made a few of these planes in their original pattern with snecked irons. I have been uneasy about putting an adjuster on this plane, but I have made a few to special request–Norris did make a few similar planes for a special order with adjuster, the rear infill was modified and did not look as nice as the pear shaped original.

From the collector’s point of view, this Improved version of the A11 mitre plane provided yet another variation to appreciate. There are a number of variations of infills on the Improved Pattern mitre planes: the range of Spiers’ cello-like shape, early to late; the rounded infills on the early Mathiesons; the ‘pear shape’ on the early Norris; Norris’ later, more monolithic infill shape.

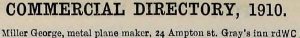

Buck/Miller

Miller shoulder plane, 1 1/2″, in gunmetal. Marked and sold as Buck, but made by George Miller who worked <1890 to 1909.

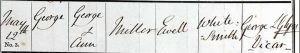

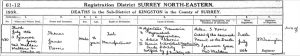

George Miller’s baptism 12 May, 1845, at St. Mary’s church in Ewell, Surrey. George Sr.: “White Smith.”

George Miller Jr. was born in Ewell, Surrey, in 1843.

In rare instances, Buck stamps can be found without the address following. In most of these cases, it’s a shoulder or rabbet plane, but there are some examples of bench and mitre planes with this singular mark. If a one-off type plane has this “BUCK” mark–caveat emptor. It’s one of the easier forgeries.

George married Jane Clark at St. Savior’s Church, Pimlico, on 26 February, 1870, and they had one son, Rumsey George (1882-1951).

A ‘whitesmith’ was an archaic term for a tradesperson who finishes off iron or tin (white metal), usually associated with milling, turning, and polishing in addition to forging (blacksmithing). A sound background for George Miller, who went on to become one of the finest infill planemakers. George Miller Sr., born circa 1819, was a whitesmith, and surely shared his skills with his son.

Rumsey G. was married briefly in 1902, but was a single railroad clerk living with his father in 1909. Rumsey died in Southend-on-Sea, Essex, in the fall of 1951.

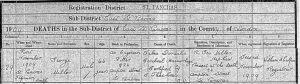

Tabes Dorsalis is nerve degeneration caused by advanced syphilis infection.

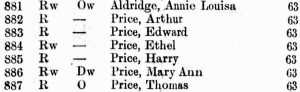

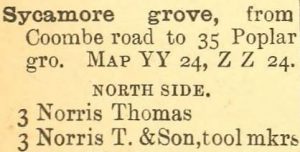

Miller’s business listings in the trade directories were few and far between.

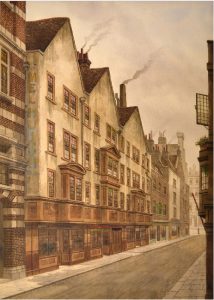

Watercolour painting of the Melhuish store on Fetter Lane, by James Lawson Stewart, circa 1840-1870.

Holland and Miller:

Over the years, a theory of continuity has been put forward, that George Miller took over the business of John Holland, and that Arthur Price took over George Miller’s business. I have also heard a version of this where Miller took over the business of Slater.

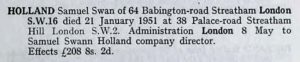

Historically, little had been known about George Miller (1843-1909), and his record in the London Street Directories was spotty at best. As seen in his census entries, Miller was only a dozen plus years younger than Holland. John Holland (1830-1912) outlived Miller by three years. Even if one accounts for Holland’s disability retirement in his final years, it was documented that Holland was still listed in the trade directories as as a “Tool Manufacturer” as late as 1907.

In the 1881 U.K. census, son Harold Charles Holland was listed as a “Tool Manufacturer,” along with his father. Furthermore, Harold Charles was a tool dealer, as declared in his 1911 U.K. census entry. Samuel Swann (Swann was his mother’s maiden name) was a joiner and shopfitter. So John Holland’s business legacy was already being carried forth by his sons in two areas.

“H.C. and S. [Samuel] Holland 70 Falcon Road Clapham Junction.” 1/4″ Side Bead moulding plane. Photo from G.& M. Tool Sales, U.K., 2020.

George Miller confined his planemaking to shoulder, bullnose, chariot, and a few smooth planes as well. In contrast, John Holland carried a full line of planes. If Miller took over from Holland, why would the product line be so radically reduced? This theoretical transition would have happened just after the turn of the new century–at a time when business was still good for infill planemakers.

Harry Charles was possibly named after Charles Badger, as John Holland took over Charles Badger’s shop at 93 York Road in 1870. Harry C. maintained his tool and cutlery store at 25 Falcon Road, Clapham Junction, Battersea from 1892 until 1925. A second store at 38 Vanston Place, Walham Green, Fulham was opened between 1905 and 1915.

Miller and Price:

If Arthur Price took over the business of George Miller, it would not have been a direct continuity, as Arthur was only 12 years old when George Miller died in 1909. Like so many other planemakers, Arthur Price got his start in the woodworking trade from his father, who in this case was Thomas Price (1857-1929), “Ship’s Joiner,” at “Harland & Wolff, Belfast and London.” In 1911, Harland & Wolff was busy building three Olympic class ocean liners, including the “Titanic.” Harland & Wolff is still in business today.

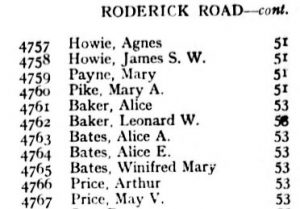

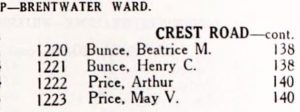

Goodman’s British Planemakers, Fourth Edition by Jane Rees, continues to have two addresses for Arthur Price, both in Northwest London: 140 Crest Road., Cricklewood (1924-1967), and 63 Carlton St., Kentish Town (1934-1965).

Arthur Price did not post his vocation in the city directories, so that did not help with searching his elusive listings. I have tried to piece together Price’s addresses using census, electoral register, and probate calendar entries. Thomas Price, a shipwright, lived at 63 Carlton St. during the 1901 U.K. census, with his own family and two other families as well.

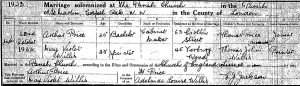

The Price family remained at 63 Carlton St. for the 1911 census. Arthur Price appeared in the 1921 Electoral Register at 63 Carlton St., along with his parents, Mary Ann and Thomas.

During the Depression, starting in 1929, and continuing through 1933, Arthur’s siblings, Edward, Ethel, and Harry joined them at 63 Carlton St. This was the final entry for Thomas Price, as he passed away in 1929.

In the fall of 1933, Arthur Price and May Violet Willis married, and were living at 53 Roderick Rd. in the 1934 Electoral Register. May and Arthur were still living at 53 Roderick Rd. in 1946. Around 1940, Arthur Price printed a trade notice, which continued to show 63 Carlton St. as his address. Carlton St. was changed to Carltoun St. just before WWII, and then was changed again to Grafton Rd. after redevelopment in the mid-1980s. Listings for Arthur and May V. Price in the Electoral Register, at 140 Crest Road, Cricklewood, started in 1949 and continued through 1956. On 5 December, 1967, the Probate Calendar listed Arthur Price at 140 Crest Road. In a nutshell, I found Arthur Price at 63 Carlton/Carltoun St., Kentish Town (<1901-1967), 53 Roderick Rd., Hampstead (<1934-1946>), and 140 Crest Road, Cricklewood (<1949-1967).

Arthur Price married May Violet Willis at St. Martin’s Gospel Oak Church, N.W. London, 22 October, 1933.

Arthur and May had no children.

Arthur Price “Cabinet, Joiner,”and May V. Willis living at 53 Roderick Rd., Hampstead in the 1939 War Register.

Arthur and May were both born in 1897. It appears that Arthur was assigned to be a telecommunications mechanic during the war years.

Arthur Price was the last infill planemaker in an unbroken tradition from the great 19th century makers. His product offerings were limited to the shoulder and bullnose types of planes.

George Miller and Arthur Price were similar–insofar that the shoulder plane was the basis of both their product lines.

The following account established that Arthur Price continued to make planes at 63 Carltoun St. until his death in 1967. This quote is about conserving the remains of Arthur Price’s workshop, as explained by Lawrence Hill, who used to work for Phillip Walker :

Philip Walker the founder of TATHS cleared Arthur Price’s workshop in 1979 or 1980 (when I worked for PGW) which is when a sheaf of the glossy handbills were acquired. If I recall rightly the workshop was an adjunct to his house – which by then was in a pretty ropey state – and relied on a human powered surface ‘grinder’ which was actually a spike running on a pulley wheel and rope drive used to surface the castings.

I still have a couple or three Price planes (these were finished and ‘stamped’ but unfitted/no infill castings which work fantastically and I also had machined about thirty of the castings for the simpler shoulder planes. The gunmetal shoulder plane is almost too good to use in the workshop…

The handbills must be just pre-war as Carlton St was renamed Carltoun St between 1936 and 1939 then renamed Grafton Road in about 1985-ish when redeveloped as flats across both the original Grafton Road and Carltoun St.

Generally a pretty run down area. …Chalk Farm estate (notorious for its riots ) is next door to this bit of Kentish Town.

Planes are very similar to some of the Norris styles – Price was making two distinct styles of shoulder plane – the gunmetal or steel ones with projecting ‘ears’ for want of a better word (i.e. York pattern, and as shown on the handbill) and what we found in the workshop in 1980 must have constituted his last batch of annealed iron ones with the ‘upright only’ London grips (not illustrated). These were mainly rough castings going a bit rusty in the ‘shop. I finished off a couple of the latter (not very well and one has the milling marks where I overdid it a bit). But this style looks much more ‘Slater’ than Norris.

Norris did make a similar profile but dovetailed, not cast, so this leads me to wonder even further about what deals might, or might not, have been done when T Norris proper wound up and broke up the business to ‘Norris Planes and Tools’ at the Croydon address; and possibly some of the Norris casting patterns went to Price. Or maybe he simply plagiarized. As the new Norris (Croydon) planes were all cast steel channel bench planes they probably constituted a very different manufacturing set up. Price already had the gear to dress small castings.

From the UKworkshop, 12 November, 2013.

Unfortunately, this was a rough way to go out.

May Violet Price (née Willis) was buried at the Trent Park Cemetery, in Islington, 13 December. 1978.

May Violet Price passed away on 7 December, 1978, with probate on 12 February, 1979. This was probably why (not definitively proven) Price’s workshop at 63 Carltoun St. remained intact after Arthur’s death in 1967 right up until 1979, when Philip Walker went in to salvage what was left.

For someone who had essentially outlived the market for his products, Arthur Price saved an impressive amount of money.

A. Price bullnose plane, heel. The iron was numbered to the plane and the wedge, all bearing the number 4.

Arthur Price’s decision to make the shoulder and bullnose planes was likely related to the fact that these models had been dropped from the Norris line either before or during WWII. Arthur found a niche and filled it.

A box of patterns, the handbills, and a number of unfinished planes ended up in the Ken Hawley Collection, housed in the University of Sheffield.. This assortment of artifacts represent a unique window into the daily workings of an infill planemaker.

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

NORRIS A11 MITRE PLANE

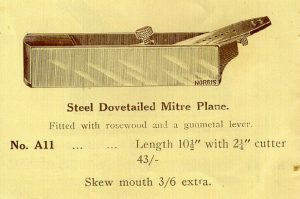

In the late 1920s, Norris decided to make a mitre plane with a 1922 patent adjusting feature, consistent with the practice of applying their adjuster to most planes throughout Norris’ product line. When considering the mitre for the adjuster, Norris chose the traditional box mitre over the the improved mitre, despite the fact that the no. 10 had been discontinued by the time of their 1914 catalog publication. During the 1920s, the Norris’ no. 11 Improved pattern mitre had a limited availability, typically rebadged as a Mathiesen Improved mitre. It is unclear whether or not Norris’ decision was for practicality reasons or for marketing purposes–or perhaps a bit of both. Nevertheless, its rather moot, because so precious few of these planes were made in the 1930s. As a result of the scarcity and expense of original A11s, interest has been generated sufficiently for several modern makers to reproduce this design.

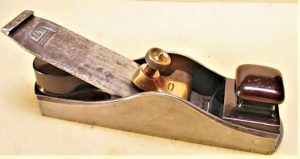

Some streamlining was apparent in the A11’s layout. Lack of a front plate eliminated the dovetailing that would have been necessary for that part, and the open heel obviated a need to bend the sidewalls. Fitting the 1922 Patent Adjuster to the A11 would have been a task well practiced by the time a traditional Norris mitre entered the planning stages during the late 1920s.

A11 mitre planes were primarily offered with a 2 1/4″ iron, and a skewed iron was available at extra cost. Price for the A11 was 43/-, which would be £145 or $183, factoring inflation by 2019. For certain, this was depression era pricing. When a Norris mitre plane comes to auction in our current market, high prices (very) are still realized, but it should be understood that a plane such as an A11 is not generally seen as a commodity, but rather as an artifact with historical, aesthetic, even practical significance. The same could be said of any number of fine antique tools.

Without a flange at the front or back, all 10 1/2″ length of the plane comprises the body, which is taller than any other box mitre at 2 1/4″. Tall sides furnish the A11 with ample area to register the plane on its side on a shoot board–with almost as much area as the sole itself. The extended infill at the heel adds mass, and the overall size of the A11 approaches panel plane territory.

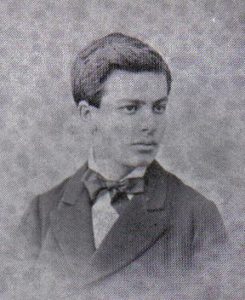

Maurice Fraser (1928-2016), was a New York City woodworker, educator, and harpsichord technician. Fraser, a well known woodworking teacher at the Crafts Students League of the YMCA in New York, explored the relationship between Leonard Bailey’s Cabinetmakers’ Block Plane, developed in the early 1860s, and the Norris A11, introduced circa 1929:

In about 1938, a couple years before its wartime hibernation, Norris produced a screw-adjustable cut on its mitre plane; its model no. 11 was now the no. A11. (A is for adjustable). All this was taking place about 75 years after American Leonard Bailey designed his adjustable block mitre, marketed by Stanley as the no. 9 “pianomakers’ block plane.” The new Norris adjustable model with its sensible return to the old-fashioned oblong body pattern, somewhat resembles its American ancestor and both were World War II casualties: neither was reissued after the war. The Stanley, at least, had been available for a respectable period, from around 1868 to 1943. The Norris, on the other hand, died virtually a crib death. The wonder is that any made it onto the market in its brief two to three year period.

…It is particularly satisfying to note that this particular tool, Norris’ last gasp in this genre, fittingly, was destined to be used as a pianomaker’s plane; precisely the same traditional function as that described by Bailey for his Stanley no. 9, the original adjustable block mitre plane.

In the ensuing 30 years since Maurice Fraser had written this article, new evidence has come to light which has expanded the years of production for both planes. Leonard Bailey’s Cabinetmakers’ Block Plane was included in the 1864 Bliven & Mead Tool Catalogue, so market penetration for this plane was 1863 or earlier. Further research by John Wells, in the late 1990s, revealed that Bailey was producing his first version of the No. 9 Mitre plane in 1858. The Norris no. A11 was included in Norris’ 1930 catalogue as well as the Buck & Ryan 1938 catalogue, so the years of production for the A11 were roughly 1929 to 1941. And a few more Norris A11 mitre planes have surfaced since 1990, commensurate with a limited output that lasted as long as a dozen years. Nevertheless, the points Fraser was making here still remain valid.

To the extent that the A11 is stark, it also appears authoritative, even imposing. Pictures are the next best thing. Shown below are two images of a Norris A11 mitre plane that came to the March 2016 David Stanley auction in Leicester, England. Photos by David Stanley Auctions.

No. A11 was the last mitre plane produced by a classic maker until the form was revived in the late 1970s. And it was also the only historical mitre plane other than Stanley’s No. 9 to have an adjuster added as a feature. This did not necessarily make it a better plane, although perhaps more convenient to use.

Norris no. A11 adjustable mitre plane as it appeared in the 1938 Buck and Ryan catalogue. By this late date, no rebadging was made for the bought in planes.

When this plane was extended back in the 1930s, the A11 was expensive, but it was not a collector’s item. The original owner may have had a good reason for making this change.

The following photos come from David Stanley Auctions in Leicester, U.K., from the sale of a Norris A11, lot No. 941 in their November, 2022 Auction:

Modern makers of A11 replicas have included Karl Holtey, Bill Carter, Darryl Hutchinson, Gerd Fritsche, Brian Buckner, and Allan Morris. Karl Holtey called the A11 “a good all round plane.”

Dovetailed A11 mitre plane, made by Allan Morris, through the legacy of Thomas Norris. Excellent workmanship, and a good likeness.

This Morris mitre plane was made in England in 2013. Its lever cap closely matches the dimensions and contours of the Norris Nos. 10 and 11 mitre planes shown on this page, in particular, the example which sold in the November 2022 David Stanley Auction.

“I have never heard of this maker but the craftsmanship is of the absolute finest quality.” –Jim Bode

Morris’ A11 has the classic protruding ‘boat-stern’ heel featured on the original Norris A11, and also duplicates the adjustment knob placement under the iron. The front and rear sole pieces are joined by a tongue and groove joint, and the mouth is as tight as reasonably possible.

Norris: The Late Years

Norris employee Charles Henry Payne worked for the Norris family in the 1920s and ’30s, and as a child visited Norris Sr. at his Quarry road Wandsworth residence. Along with Thomas Jr.’s wife Helen Sellars Walker (1865-1952), Thomas’ sister Elizabeth (1870-1949), became more active in the late 1920s and early 1930s with maintaining the family business. Payne’s grandson learned about Charles’ experience with working for the Norris firm through his father. Charles Henry had some important insights into how the Norris business was run in the 1920s and early 1930s:

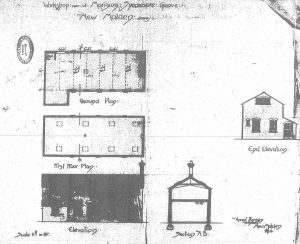

Proposed 1906 floor plan and elevation for the Norris Workshop/factory at 3 Sycamore Grove, New Malden, U.K. From collection of George Anderson

…Norris never employed a large number of staff; they tended to have a number of out-workers who would do small batches of work when it was available. In addition, the [Norris] company were primarily assemblers and finishers. Cutting irons were obtained from firms in Sheffield as were the plates for the bases and sides of the dovetailed planes. [The soles and sidewalls] were apparently already stamped out into their basic shape. Castings came from foundries in the Bermondsey area of London. ...batches of cutters were always measured for thickness as they tended to vary somewhat. …[Measuring the thickness of irons] allowed planes to be selectively assembled to maintain consistent mouth clearances.

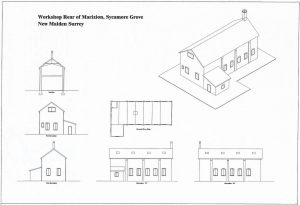

Modern reworking of floor plan and elevation for Norris workshop/factory at 3 Sycamore Grove, New Malden. From the collection of George Anderson

The era of fine dovetailed infill planes was coming to a close. Wage inflation, competition on the low end from Stanley, and mechanization/power tools brought pressure from all directions. Thomas J. Norris passed away in 1936, leaving what was left of Norris’ business to be run by his widow, Helen Sellars and his sister Elizabeth Norris.

Results in Thomas Jr.’s death certificate revealed why Elizabeth Norris became active in running the business in the late 1920s, along with Helen Sellars Walker. Thomas Jr. was suffering from senility, among other ailments. Multiple causes of death were also a result of advances in diagnostic procedures for medicine as compared to the 19th century

£3640 would be just under $340,000 in today’s money.

Thomas had done all he could to sustain the company: by inventing the 1913 and 1922 patent adjusters, and by keeping production standards as high as reasonably possible. Norris infill planes remained relevant up to the middle of the 20th century, but the times were changing. Humanity was toiling through a worldwide Great Depression, and running inexorably towards World War Two. A11 mitres were all but finished by the time of the 1938 Buck and Ryan catalogue. Norris struggled on with a skeleton crew of four until 1943, according to former employee W. J. Yarrington. Most of the remaining production was done on dovetailed smoothers, with a few dovetailed panel planes and cast phosphor bronze violin planes.

Burnishing part of a pocket knife at Stan Shaw’s Knifeworks. Photo by Geoff Tweedale, Sheffield City Archives.

During his Norris apprenticeship, Yarrington learned metal burnishing skills, which he never had a chance to use again, despite spending his working life in the toolmaking trade. Today, burnishing metal surfaces by hand is rarely encountered outside of burnishing over the edge of a scraper blade, or in jewelry making.

E. Guymer, a friend of Thomas Norris in the 1920s and ’30s, described the Norris workshop in an August 1983 article in Woodworker Magazine (U.K.):

Orderliness prevailed. There was a loft full of hard wood, mostly rosewood seasoning over the years, and this, with the machines, tools and materials in the workshop were treated with a respect amounting almost to reverence. Integrity was the key to Tom Norris’ life and work, from the largest jack planes to the smallest bronze violin-making planes; the latter little larger than my fingernail, but with a cutting iron ground, tempered and honed with as much care as it’s largest brothers. There was a press where the steel was formed for the dovetailed frames; a grindstone and a furnace, polishing machines, drilling machines and much besides

When work on Norris planes restarted after the War in 1946, it was with new owners, and with a changed product that got the job done, but was of a different caliber altogether.

Victorian house on Sycamore Grove, similar to that of Thomas Norris Jr.’s. Possibly constructed by the same builder. Photo by George Anderson.

The following quote also came from Maurice Fraser, regarding the 1989 David Stanley auction price of a custom Norris A11 mitre plane. Leslie Ward (1901-1980) was the head harpsichord maker for Arnold Dolmetsch (1858-1940), a leader in the original instrument revival movement. Ward commissioned this mitre plane to his own specifications in the late 1930s:

Its rare with historical artifacts such as these, that we are afforded any knowledge of the person behind the tool. …Dolmetch (1858-1940) was the most powerful force in the phenomenal 20th-century revival of historical musical instrument manufacturing. The Dolmetsch factory in Haslemere, Surrey, England, occupies the site where those still-famous harpsichords, lutes, viols and recorders first saw light again, under the hands of such craftsmen as Ward and others… Ward remained head of the harpsichord and clavichord division until his retirement in 1966.

A Little More On Arnold Dolmetsch:

The Dolmetsch-Guillouard business was renamed Gouge-Guillouard after Arnold’s mother’s remarriage. Image from Dr. Brian Blood, Dolmetsch.com

Arnold Dolmetsch was born 24 February, 1858, to Rudolf Dolmetsch and Marie Guillouard in Lemans, France. The Dolmetsch family was originally from Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). Young Arnold grew up playing the violin, and doing craft work in his parents’ piano business. This experience was invaluable for preparing young Arnold in making his own instruments later.

Early music and instruments of the Renaissance and Baroque periods were not completely forgotten during the Romantic period of the 19th century: mostly though, the interest was limited to antiquarians, collectors, and scholars. There were a few isolated performances, such as Felix Mendelsohn’s presentation of an abbreviated version of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in 1829.

A.J. Hipkins playing his Abraham Kirckman c. 1770 two manual harpsichord, with elaborate walnut-burl veneers. Painting by Edith J. Hipkins, Albert’s daughter, oil on canvas, 1898.

As a young violin student studying at the the Brussels Conservatory, Arnold heard a performance of some early recorder music, which he apparently really liked. In 1879, Arnold Dolmetsch attended a performance of Renaissance and Baroque instruments at the Paris Conservatoire, after which, he bought a viola d’amore, restored it, and began to collect other historical instruments. Around this time, the research of Alfred James Hipkins (1826-1903) became known to Arnold Dolmetsch. Hipkins was a scholar of antique musical instruments from around the world, which was rather unique for the time, but foremost, he was an expert on keyboard instruments.

In 1846, 20 year old A. J. Hipkins was charged with training the in-house staff of piano tuners at the pianomaker Broadwood in the art of setting an equal temperament for their piano tunings. Hipkins wrote two important books: Musical Instruments Historic, Rare, and Unique (1888), and A Description and History of the Pianoforte and of the Older Keyboard Stringed Instruments. (1896).

When Frederic Chopin toured England in 1848, he stayed in the U.K. for 7 months. Chopin performed multiple concerts on Broadwood pianos, and these were tuned and prepared for him by A.J. Hipkins, who was a valued employee of Broadwood for his long working life. While the following quote from Hipkins on Chopin’s piano playing is somewhat of a detour from Dolmetsch and early music, it is interesting to note how important J.S. Bach (1685-1750) was to Chopin as a musician:

[Chopin] was frequently at Broadwoods: of middle height, with a pleasant face, a mass of fair curly hair like an angel, and agree-able manners. But he was something of a dandy, very particular about the cut and colour of his clothes.

He was painstaking in the choice of the pianos he was to play upon anywhere, as

he was in his dress, his hair, his gloves, his French; you cannot imagine a more per-

fect technique than he possessed! But he abhorred banging a piano; his forte was

relative, not absolute; it was based upon his exquisite pianos and pianissimos—

always a waving line, crescendo and diminuendo. . . He especially liked Broadwood’s Boudoir cottage pianos . . .two-stringed, but very sweet instruments, and he found pleasure in playing them.He played Bach’s ‘48’ all his life long. “I don’t practice my own compositions,” he said to Von Lenz. When I am about to give a concert, I close my doors for a time and play Bach.”

— Edith J. Hipkins, How Chopin Played.

From Contemporary Impressions collected

from the Diaries and Note-books of the late

A. J. Hipkins, F.S.A. (London: J. M. Dent and

Sons Ltd., 1937), pp. 6–7.

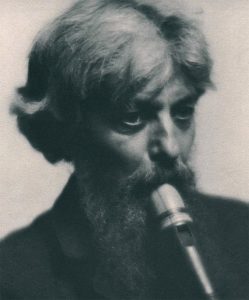

Arnold Dolmetsch (1858-1940) playing the recorder. Portrait by Alvin Langdon Coburn, 1916

During the 1890s, Arnold Dolmetsch started making his own historically inspired instruments: Lutes (1893); Clavichords (1894); large Harpsichord (1896). It should be noted, however, that Pleyel, a piano manufacturer in Paris, began making harpsichords in 1888 albeit in a highly ‘modernized’ state, including an iron frame, and utilizing many stops for creating variations in sound quality.

After making about 10 clavichords on his own, along with other instruments, Dolmetsch was hired by Chickering and Sons, pianomakers in Boston, Massachussetts. Arnold remained at Chickering from 1904 until 1911, making a total of about 80 instruments. These are thought to be among the best Dolmetsch ever made throughout his life. Unfortunately, business took a downturn for Chickering around 1910, and the early music department of Chickering was discontinued.

Dolmetsch/Gaveau Ottavino Spinet, c. 1911-1914. Photo from Rosebery Auction House, London, 2017.

After Chickering, Dolmetsch went on to work at Gaveau, pianomakers in Paris, France. Arnold remained at Gaveau, making historical instruments for another three years, from 1911 until 1914.

Around 1917, the Dolmetsch family settled in Haslemere, Surrey, England, where they remained for the rest of their lives. They set up workshops for early instrument making, with Nathalie Dolmetsch (1905-1989) in charge of Viols, Carl Dolmetsch (1911-1997) in charge of Recorders, and Cecile Dolmetsch Ward (1904-1997) and Leslie Ward (1901-1980) in charge of Harpsichords and Clavichords.

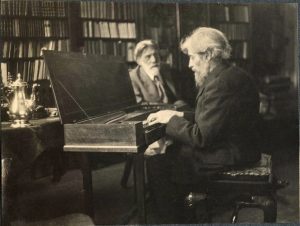

Dolmetsch playing clavichord for an audience of one. Photo from Ottoline Morell, Oct., 1924 National Portait Gallery, London.

All along, the Dolmetsch family emphasized performance as paramount in their efforts to popularize the early music, 1. by making efforts to disseminate early music performance practice, 2. by introducing hitherto unfamiliar composers and their music, such as John Jenkins and William Lawes, and 3. by establishing the Haslemere Early Music Festival in 1925. Each of the family members would perform and record, with Arnold, Mabel (1874-1963), Rudolph (1906-1942), and Carl as soloists, and the rest in ensemble groups.

Arnold Dolmetsch recording of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, Movement 1 (c. 1937), recorded by Leslie Ward and Hugh Gough (at the time studying music with Dolmetsch and later an early keyboard instrument maker).

Almost everything was done in-house, including some of the recording. In addition to running the keyboard department, Leslie Ward served as a recording engineer. Additionally, Leslie played the violone, and the bass recorder. He also registered two patents related to ‘improvements’ in jacks for harpsichords.

With the benefit of hindsight, the Dolmetsch clan has been criticized by some for their performance shortcomings, or for their lack of authenticity in reproducing historical instruments. But it has to be realized that in the early 20th century, there was was no early music performance practice to reference, and no living instrument makers to consult. Also, there were no significant financial resources to tap for the Dolmetsch family to popularize early music. Yet almost every person in early music circles in England, and to a lesser extent in the United States, has been touched by Dolmetsch, however indirectly.

Sopwith Triplane reproduction, in a steep climb. Photo from wikipedia.

Leslie Ward apprenticed with Thomas Sopwith during WWI; Sopwith Aviation made some of the most important airplanes of WWI, including the iconic Sopwith Camel.

During WWII, the Dolmetsch Workshops were converted to make aircraft parts from vulcanized fibre and plastic. This early experience with plastics in production led to the introduction of the Dolmetsch Bakelite recorder line in 1947. Dolmetsch Bakelite recorders were not the first plastic recorders, however. That distinction belonged to Schott & Co., of England, under the direction of Edgar Hunt during WWII. Dolmetsch recorders were used extensively throughout the United Kingdom in music education programs, at many levels. In around 1974, Dolmetsch Workshops introduced ABS plastics for their mass-produced recorders.

“The Dolmetsch Workshops.” by Leslie Ward. Catalogue of Dolmetsch instruments, published from the 1940s to the 1960s.

Leslie Ward served as the writer for the Dolmetsch trade publication. Ward would also restore historical instruments in addition to making the new reproduced harpsichords and clavichords.

NORRIS A11 MITRE PLANE (cont.)

New Malden is just Southwest of Wimbledon Park, and Haslemere is in the extreme Southwest end of Surrey County. It was possible to ride the train from Waterloo Station in London to New Malden, and then on to Haslemere.

Weller Map of Surrey County, England, c. 1895, showing Norris in New Malden, and Dolmetsch in Haslemere

Cutting out a bridge for a bass viol with a fret saw at the Dolmetsch Workshop, c. 1957; Norris 18 or 20 Shoulder plane.

Here is Maurice Fraser again, regarding the 1989 David Stanley auction price of Leslie Ward’s custom Norris A11 Improved Pattern mitre plane:

The extravagant 1989 price for Ward’s Norris mitre plane is an odd mix of reverence and irrationality. Today, the astronomical pricing of what is perceived as art is little questioned, even though what is art is ever more difficult to ascertain.

This tool, at least, has both beauty and utility. And it is a piece of technological history–a cultural icon. How do you price a revered object? Especially given the dynamics of an auction, which reveal the marketplace at its most emotional; an arena of contradiction where, in the heat of battle cool reason is often overcome.

The successful bidder, Max Ott, is a long time professional woodworker, tool collector and currently the owner and manager of a cabinet shop in London. The proud new owner, soberly, is reserving the tool for private use in his home workshop. Pleasure, not profit. But it has always been that way. Commercially, the mitre plane has always been a loser: it promotes quality unhurried–not quantity, requisite in the press of the late machine age.

Maurice Fraser “Fine Woodworking,” New York, N.Y. 1990

Norris A11 Improved mitre plane, showing boat-shaped stern. Edmund Norris (1837-1928), brother of Thomas Norris Sr., was a shipbuilder.

Norris A11 Improved Mitre reproduction, c. 1990. The original plane made quite a stir when it came to market in 1989.

Norris A11 Improved Mitre plane reproduction, by Geoff Entwistle. Photo by David Stanley Auctions, 2015.

Entwistle’s copy of the Norris A11 custom improved mitre plane was one of the more faithful reproductions of this plane. It was reduced in size to the proportions of a British thumb plane, to make it more handy.

Ward’s decision to commission his Norris Improved A11 was very much in the spirit of the times and of the Dolmetsch workshop: which, in terms of instrument-making meant that changes over time represented ‘progress.’ An historically correct choice for a mitre plane would have been an early Gabriel from the late 1780s. Would that have made a difference to the wood? Not in and of itself.

H.C. Holland jointing plane reference, on HackneyTools.com in 2017