Stanley’s “Imp” that was featured on the cover of their pocket catalogues from c.1888 to c.1902. From 1902 catalogue.

Stanley’s advertising department began showing a depiction of an Imp riding on a Stanley Excelsior (rear-biased cheeks) 9 1/2 style block plane on the covers of their pocket catalogues, in 1888. Stanley continued to show the Imp there, as well as on the back of some catalogues, through 1902. The Imp was shown riding on the block plane with bridles, as if the plane was a carriage. For the last appearance of the Imp in 1902, the block plane still showed the Excelsior style, but with the newer “handy-grip” cheeks, which were patented by Justus A. Traut in 1897, and introduced on their block planes in 1898. Excelsior style block planes with the “handy- grip” sides were only made for several months during 1898, after which, the rise in the sidewalls was moved to the center of the plane.

Features shown in this drawing are not current with production at the time, and show artistic license. The adjusting knob shown is a pre-eccentric lever, and the lever cap is an earlier version. For that matter, the Excelsior body had been out of production for four years by the time this drawing was published in 1902.

I have observed a number of these Stanley block planes that were made in 1898, and have noticed that there are many (but not all) with a small crack on the right cheek. This crack is usually located where the lateral adjustment lever, which is biased to the right side of the planes’ interior, makes contact with the inside of the right cheek. Since the castings of the Excelsior planes is fairly elegant, but thin, and the thickness of the sides taper towards the edges, the iron casting is vulnerable at this area. If an owner forced the lateral adjustment lever over to the right, under the full tension of the lever cap, the impact with the rear-biased right cheek could crack. Fragility in the right cheek area on these 1898 Stanley block planes was increased with the introduction of the “handy-grip” feature, which thinned down the cheeks even further.

Stanley Bailey block planes, Nos. 19, 15, and 9 1/2, all made in 1898 with Excelsior body and handy-hold cheeks.

In the late 1890s, no one told tradespeople to baby their new Stanley block planes. So the crack in the cheek became a fairly common occurrence. Moving the crest of the sidewalls to the center of the block planes eliminated the collision of the lateral lever with the inside of the right cheek.

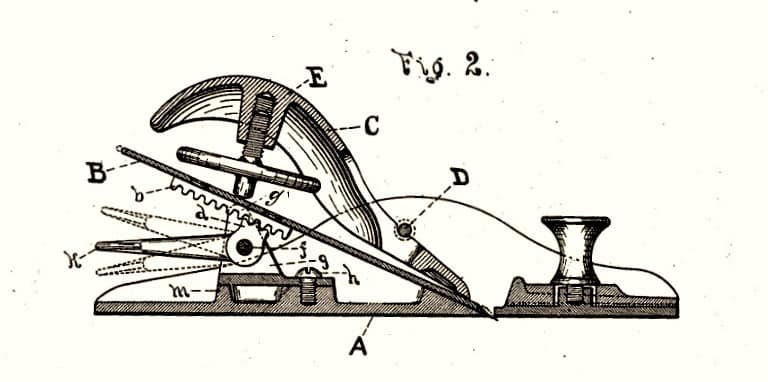

The early versions of the No.9 1/2 block planes had a cutter depth adjustment lever which moved side to side, patented 22 June, 1858. This lever had a pin which worked on the bottom of the iron, and it was not robust. After c. 1875, the 9 1/2 type adjuster was changed to the vertical post and lever which was derived from Leonard Bailey’s patent of 6 August, 1867.

On the version 3 of the Stanley No. 9 1/2 block plane, c. 1875-1878, you can see part of the brass thumb wheel, which runs on the threaded vertical post, and engages a notched lever, for adjustment of the iron.

Interior of Stanley Excelsior No. 19, showing leveral lever with 4 patents, eccentric lever for mouth adjustment, patent 1894, and “J” logo iron (1874-1909).

The Stanley Bailey Excelsior Block Plane had undergone almost 30 years of refinements by the time the Stanley No. 19 shown on the left, was produced. Modern features were included in this late example. This was the mature Excelsior.

When Stanley made some newer iterations of their No. 9 1/2 block plane, they have chosen to develop profiles that show some influence from the Excelsior shape. Personally, I prefer the old ones.

Stanley No. 19, 15, and 9 12: Last of the Excelsiors, c. 1898. Right side view. These block planes contain the best of two worlds: the elegance of the old Excelsior form, and the consummation of thirty years of innovations by Stanley in the late 19th century.

Stanley No. 65 Low Angle Block Planes and Their Equivalents

Two Stanley no. 65 planes. Front: circa 1947-1953; back: circa 1936-1946. The Stanley No. 65 Low Angle block plane was one of their high end planes: a full-sized 7 inches long, with a 1 5/8″ iron, featuring a knuckle cap, and an iron bedded at 12 degrees. The plane featured Justus A. Traut’s Patent direct-drive iron adjuster, 1897-1900.

Stanley 65 c. 1947-1953 in foreground, showing reduced bed area for the iron. You can see that by the late 1940s, early 1950s, Stanley was beginning to reduce the amount of machined bedding area for the iron. This was done in an effort to reduce costs as Stanley had to absorb more labor expenses as the years progressed. Machined runners on the sides of the bedding area behind the throat were utilized to help support the iron. Other late changes to the No. 65 block plane are not consequential, but can help indicate what type of bedding area may be inside: Back of adjusting knob flat–mid-late 1950s; tab on eccentric lever turned up–c. 1960; top of sidewalls painted–c. 1960-1962; blue japanning–c. 1962-1967; return to nickel plated cam lock lever cap–c. 1964-1969 (end of 65 production).

Other late changes to the No. 65 block plane are not consequential, but can help indicate what type of bedding area may be inside: Back of adjusting knob flat–mid-late 1950s; tab on eccentric lever turned up–c. 1960; top of sidewalls painted–c. 1960-1962; blue japanning–c. 1962-1967; return to nickel plated cam lock lever cap–c. 1964-1969 (end of 65 production).

Stanley no. 60 low angle block plane, early 1980s. Later on in the 1950s, these runners were eliminated, and the support area was reduced to a machined narrow strip just behind the the mouth. This does not necessarily make these block planes junk, because with the deflection of the thin iron under pressure from the the lever cap, the really critical bedding area in these planes is between the leading edge of the lever cap and the rear edge of the throat. In some block planes, the fore and aft adjustment connection to the back of the iron is slightly higher than that of the angle of the bedding area behind the mouth. And the downward flexing of the thin cutter under the pressure from the lever cap improves the contact area to an extent. That said, more bedding contact area is better than less.

Two Stanley No. 65 low angle block planes. Around 1947, Stanley stamped the left sides of a number of their block plane models with the model designation. That makes it easy to determine those no. 65 block planes made in 1947 or later.

The Hungarian-American photographer Lazlo took some interesting images of the old Stanley Works in New Britain, CT, before demolition in 2018. You can see those photographs here. Some factory spaces look dreary, and it’s hard to imagine being productive in that environment.

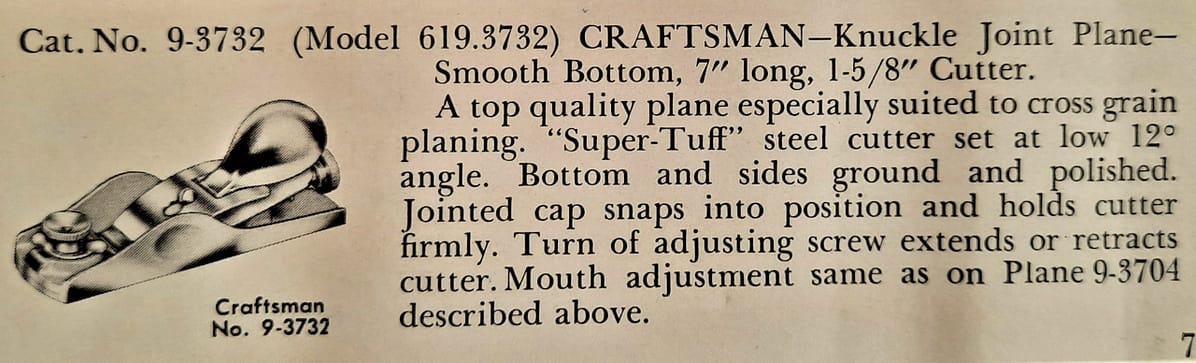

Sears Roebuck & Co., No. 3732 Low Angle Block Planes

Sears & Roebuck introduced their large catalogues in the 1890s, and from early on, they had no trouble picking out some of the most desirable planes that Stanley had to offer. Interestingly, in Sears’ early years, no rebadging was done on the Stanley planes. Also included in the 1900 Sears Catalogue, was the favorite Stanley No. 140 block rebate plane.

“Genuine Bailey Iron Cabinetmakers’ Adjustable Block Plane No. 9.” Otherwise known as the Bailey Stanley Pianomakers’ Mitre Plane. It is quite something, that in 1900, a piano factory worker or cabinetmaker could buy a No. 9 from a Sears Catalogue! This reminds me of the experience of buying my Lie Neilsen No. 9 Mitre plane brand new from “Japan Woodworker” in Alameda, CA almost a century later (closed in 2012).

Almost 20 years onwards, Sears & Roebuck was still offering Stanley planes under their original name. These Stanley planes were offered alongside Sears’ in-house Fulton planes line. Fifty years later, Sears would finally contract with Stanley to rebadge Stanley planes as in-house Craftsman planes.

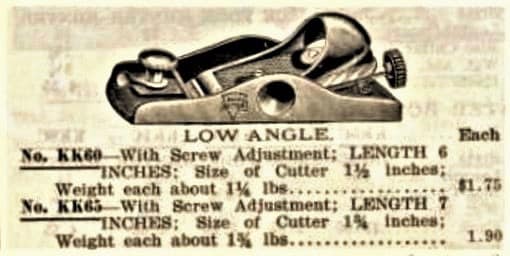

By 1904, Sears established its in-house plane brand, “Fulton,” which they continued until 1944. Sears’ Headquarters, The Enterprise building, had frontage on four streets in Chicago, including Fulton St. This is most likely where the name for the line of Sears plane came from. Other lines included Dunlap, Sears’ line of economy planes, and Merit. This 1911 Sears Catalogue excerpt shows what looks to be a Sargent 5306 type block plane. At the time of this catalogue, this lever cap design was only 2 years old, and the adjustable mouth design was 5 years old.

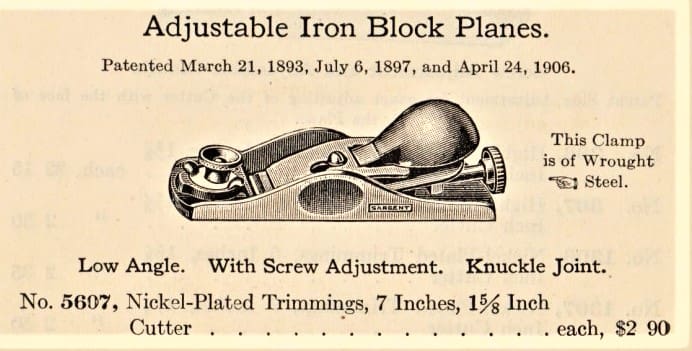

“This Clamp is of Wrought Steel,” proclaimed the Sargent Co. in the 1926 introduction of their 5607 Low Angle Block Plane, 7″ long, with 1 5/8″ cutter. This was an oblique reference to the fact that their first cast iron knuckle type cap, recorded in A.A. Page’s patent of 6 July, 1897, would crack if you looked at it funny!

Henry Sargent’s Patent for mouth adjustment, as stamped on the actual adjuster of a 5607 block plane, April 24, 1906.

The 5607 was introduced with nickel trimmings, but during World War II, that was changed to black nitrate, from 1943 to 1945, according to secondary sources. I have a suspicion that black nitrate was utilized earlier as well, probably starting in the 1930s, as a way to reduce manufacturing costs during the Great DepressionWhen Sargent introduced their No. 5607 Low Angle block plane in 1926, there were some key differences with the same plane just a few years later, in the early 1930s.

-

- Sargent No. 5607 Low Angle Block Plane. Early version, c. 1920s. View of casting. Knuckle cap marked Sargent, and nickel plated, Mouth adjusting eccentric plate was nickel plated. Also showed 1906 patent.

Craftsman 3732 (Sargent No. 5607 Low Angle Block Plane). Photo from ebay. Mouth adjusting eccentric plate was nickel plated rather than japanned. Also showed 1906 patent.

Rear adjusting knob and adjustment screw shaft a cast iron knob with a steel shaft..

Three reinforcing ribs in the center of the casting were eliminated in the 1930s.

Knuckle cap finished in black nitrate (possibly 1930s as well as 1940s).

Craftsman 3732 Low Angle Block Plane (Sargent 5607, c. 1932), and Craftsman No. 3732 Low Angle Block Plane (Sargent No. 5607, circa 1951-1961) The later redesign of the Sargent 5607 was done around 1950, and was still available in the 1960 Sears & Roebuck Catalogue. The 1951 Craftsman Pocket Catalogue was reissued in 1958, virtually unchanged, including the 5607.

Four Sargent Planes, and one West German block plane, in the 1960 Sears & Roebuck Catalogue. Craftsman 3732 (Sargent 5607) and Craftsman/Sargent “Little Shaver” planes.

The stamp shown above was the first to use the manufacturing code “BL.” This was in anticipation of introducing other manufacturers, such as Millers Falls, which occurred in 1933. From the inception of the Sears Craftsman line in 1927 until the end of 1932, all the Craftsman planes were made by Sargent. In 1951, Sears assigned the numerical code “619” for all Sargent planes rebadged as Craftsman. Stanley planes were introduced to the Craftsman line much later, in 1969. The letter code for Craftsman planes made by Stanley was “DD,” and the Craftsman/Stanley number code was “187.”

Craftsman 3732/ Sargent 5607 Low Angle Block Plane, late model, as shown in the 1951 Sears Craftsman Plane Pocket Catalogue.

A Swan Song for Sargent Planes. After 1964 Sargent continued making locks and similar hardware.

Sargent’s “Little Shaver” three inch plane, with a one inch cutter, was introduced in 1958, and still offered by Sears & Roebuck in 1964. Like the Stanley no. 101 3 inch plane, it is not a true block plane, because it has a bevel down iron. Styling on the “Little Shaver” small block plane really screams 1950s.

At some point after 1964, Great Neck Tools in Mineola, NY was thought to have bought out the remaining stock of “Little Shaver” planes still with the “BL” marked on the casting under the iron, and Great Neck Tools continued to sell this small plane in their own blister packs. After a number of years, the old Sargent inventory ran out–or Great Neck decided to change the markings on their own established production of this small plane. In the late 1970s, the “BL” mark was changed to “LSO,” and the quality really went downhill. During the late 1970s and 1980s, lever cap screws were drilled way off-center, the bridge/cross pins were installed crooked, and many of the castings were rough.

Schaff Piano Supply in Chicago carried the “LSO” version of the “Little Shaver” for decades. I bought one of these planes from Schaff in the 1970s. Great Neck continued to manufacture this plane in the U.S.A. until around 2012, They still offer it for sale imported from China. And other companies are producing this design as well, although the lever cap is now hollow underneath, and the body on some of the planes are made of aluminum.

When first introduced, the “Little Shaver” was a good value; it had much more mass in its iron casting than the equivalent Stanley No. 101 plane. The nickel plated lever cap screw was larger than that on the Stanley 101 as well, providing more leverage. My main complaint with the plane was that there was too much room on either side of the cutter which allowed the cutter to ‘wander’ off to one of the inner cheeks while in use. Other than that? A lot of bang for the buck. Literally

Millers Falls No. 47 Low Angle Block Planes (Craftsman 3732)

The Millers Falls No. 47 was very similar in appearance to the Stanley No. 65 Low Angle Block Plane. The No. 47 was a quality product, capable of yielding fine results.

Craftsman Block Planes, as included in the Sear & Roebuck 1941 Catalogue. The Millers Falls No. 47 was shown in most of the Sears and Roebuck Craftsman from 1941 to 1958. Sears gave the manufacturer’s code “BB” for Craftsman planes made by Millers Falls in 1933, and the numerical code 107 for same in 1950.

Millers Falls No. 47 Low Angle Block Plane, 7″ long, with 1 5/8″ iron. From Millers Falls 1938 Catalogue.

While Millers Falls’ No. 47 Low Angle block plane was represented in the bi-annual Sears & Roebuck Catalogues from 1941 to 1958, evidence also points to Sargent’s No. 5607 having been utilized as Craftsman 3732 in the 1930s as well as the 1950s. This evidence has been found in the examples of the Sargent 5607 Low Angle block plane with Craftsman stamps on their cutters.

The Millers Falls No. 47 block plane is a good value on the used market, as it often sells for significantly less than its Stanley No 65 counterparts. The Craftsman version usually comes with an even deeper discount. I purchased my Craftsman 3732/Millers Falls 47 in the original box for the amount that a rusty Stanley No. 65 might go for.

Millers Falls No. 47 Low Angle Block Plane, in it’s original guise. Photo from Worthpoint.com. When one compares the M-F 47 to the Stanley 65, they are very similar, however, when placed side by side, small differences appear in the details and contours. The most noticeable differences would be that the M-F 47 has a thinner casting than the Stanley 65 from the same era. The knuckle-joint lever cap is a 3 piece design rather than a 4 piece design in the Stanley knuckle joint lever cap, after its 1913 redesign. Utilizing the back of the knuckle joint would seem to be a more secure method of bolstering the locking action into place, but it is actually not quite as stable as the Stanley, in my opinion.

There was nothing wrong with the Craftsman brand. When I was a kid in the 1960s, I would always hear stories about folks returning beat-up and damaged Craftsman tools to Sears for replacement because of their unconditional guarantee at the time.

Ohio Tools Co. No. 065 Low Angle Block Plane/Keen Kutter KK 65.

Like many other competitors of Stanley, Ohio Tools Co. (Columbus, OH, and Auburn, NY) copied much around Stanley’s products, not the least of which was their model numbering system. Ohio Tools Co. simply put a “0” in front of Stanley’s model numbers. The Ohio Tools Co. low angle block planes were surprisingly sophisticated, and well made. The Marks’ Patent Lateral Adjustment feature was effective with the the Traut Direct Drive type adjustment mechanism, but had less positive performance when used with the Rack and Pinion Adjustment Lever used on early Ohio 09 1/2 models.

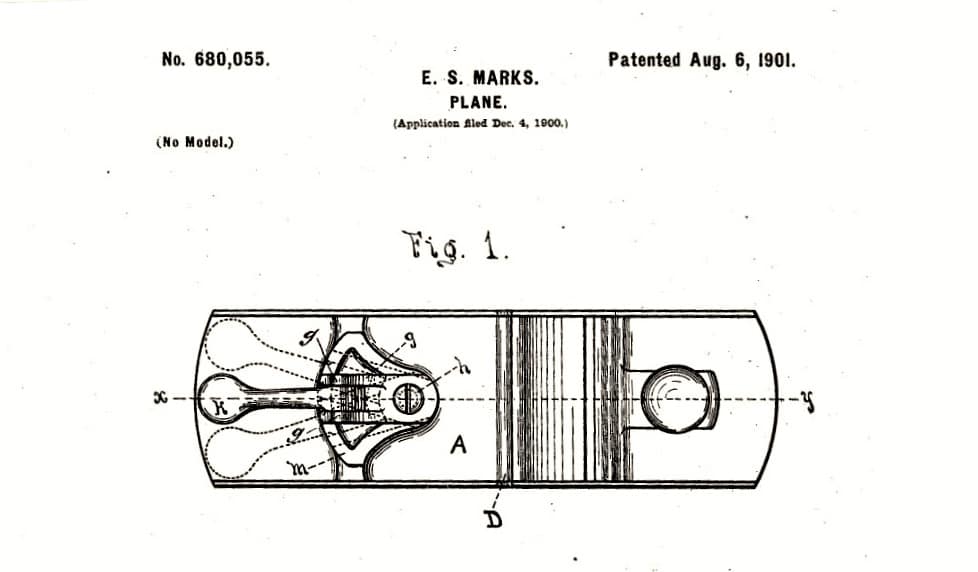

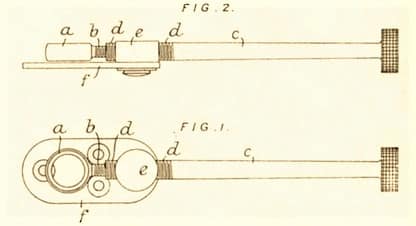

Mark’s Patent drawing Iron Adjuster in conjuction with the rack and pinion type adjuster used on the 09 1/2 type block planes, c. 1901-1905.

On the Ohio 103 block plane you can see the rack and pinion adjuster arrangement. This rack was a large attachment placed on the underside of the cutter. Next to the 103 is an Ohio 09 1/2 block plane with the Marks’ patent lateral adjustment mechanism.

Here is the patent for Edward S. Marks’ Lateral Plane Adjustment Mechanism, dated 6 August 1901. This works pretty well with the Traut-type direct drive adjustment mechanism. The mouth adjuster is also impressive.

Marks’ blade adjustment with the Traut-type adjuster bears some resemblance with the later British Norris adjuster, but they are not identical. On the Norris, the pin is located on the opposite side of the fulcrum, resulting in an inverse, or contrary, lateral movement of the iron relative to the movement of the adjustment knob. In other words, when the adjustment knob is moved to the right, the iron moves to the left. And visa versa. In Marks’ Patent, a movement of the adjustment knob to the right, moves the iron commensurately over to the right.