BUCK THUMB PLANES AND OTHERS

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

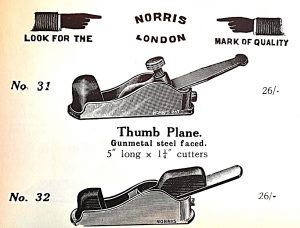

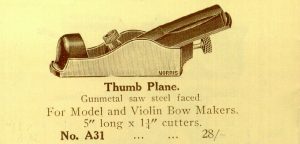

This example of a Norris A31 Thumb plane sold in 2020, for a price of $9,800.

Norris No. A 31 Adjustable Thumb plane, as depicted in the 1938 Buck & Ryan Tool Catalogue. “Favoured by Pianoforte Case Makers.”

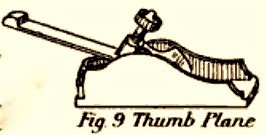

Distinctly British thumb planes were never produced in quantity; chariot planes were the most similar British plane in design and function, but chariots were made in greater quantities by a larger number of planemakers. Both chariot and thumb planes had thick bevel up irons on a wooden infill bed, around 20 degrees, with a 3 to 5 inch body respectively, and easily used with one hand. Given these similarities, the relative popularity of the 19th century chariot plane almost eclipsed the thumb plane. Certainly, some 19th century woodworkers preferred using the bullnose feature for planing in tight spots. A majority of British chariot planes had the bullnose component: with the mouth placed close to the toe.

Since so few British planemakers made thumb planes, examples are difficult to find. This lack of antique English thumb planes has created demand, so a number of current planemakers are producing new thumb planes. Interest in thumb planes today quite possibly equals that of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Small Mitre Planes: Precursors of Thumb Planes

For the purposes of this look at small British mitre planes, I have designated less than 7″ as the arbitrary cutoff point in defining a ‘small’ mitre plane. It is true that a 7″ mitre plane is small, but there are enough of those around to determine that they were not at the same level of specialization that 5″ and 6″ mitre planes were. Similar to their larger mitre plane examples, as well as the thumb planes that followed, small mitre planes had a bevel up iron, bedded at around 20 degrees. While small mitre planes were forerunners of British Thumb planes, they were also a unique category of planes in their own right, and they continued to be made by Norris as late as c. 1920.

Some well known makers of full sized mitre planes also made some very small ones, albeit in small quantities. Robert Towell was probably the earliest known maker of small English mitre planes; a handful of these survive, and some of them were bought in by George Buck of 245 Tottenham Court Road.

Sole of Towell 5″ mitre plane, showing sole joined and aligned around two short metal pins. Unusual construction.

Buck 4″ compassed mitre plane. Photo by D. Stanley Auctions, March, 2013. Probably pre-1860; maker unknown.

This unmarked 6″ Towell mitre plane appears in excellent original condition, with a Ward & Payne cutting iron,

This Holzapffel miniature mitre plane may or may not have been made by Robert Towell. There are some differences in the details, which depart from Towell’s standard practice, such as a Cupid’s Bow which was not filed at a low angle, and a wedge that was squared off at the end. Also, Towell was not known for including a nib on his irons, and this I. Sorby iron has an extra long nib or sneck. And the front infill is not extending out over the mouth as in most of Towell’s mitre planes–but I am only going from the photos, and it is a very short plane, with little room for long infills.

During the early 19th century, when Robert Towell was active, there were a few makers, either craftsmen or professionals, who made some unmarked 5″ and 6″ mitre planes. These are also quite rare, and it must be mentioned that there are a number of reproduction small mitres made in the last 45 years or so that were presented as antiques rather than as the products of a modern plane maker.

This is an unmarked 6″ x 1 13/16″ small mitre plane with a 1 1/2″ cutting iron, and dark rosewood infill. The bridge on this one looks a little like I. Smith, but the ends of the beveled cut are square, while Smith’s were rounded and angled towards the cheeks. The bridge style does date to the early 19th century in London, however. There is a rosewood overstuffing at the heel of the plane. This plane was in a noted Glasgow, Scotland collection until 2010 or so, and then marketed and sold by Lee Richmond in 2011/2012.

Stewart Spiers (1820-1899) of Ayr, Scotland also made a few small mitre planes, and they appear similar to his larger mitre planes, except scaled down in size. Here is a 6″ example sold by Jim Bode.

Edward J. Davies Mitre Plane, 4 inches long, from Janet Wells collection. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, February, 2019.

This Davies plane was almost certainly a one-off effort; a lot of care went into making it, including the bone infill and wedge. Although some have thought this plane older, I would estimate that it dates from the mid to late 19th century.

Buck/Holland 6 3/8″” mitre plane, as it appeared in the David Stanley Auction, June, 2019. Buck 247 Tottenham Court Road (1867-1879)

Buck/Holland mitre plane, 6 3/8″ long, with repaired or replaced wedge, and nibbed Ward iron, from another bevel up plane. Photo by Jim Bode.

Joseph Odling Dawe (1827-1898) was a successful Islington, London cabinetmaker and upholder. Photo by Jim Bode, c. 2017.

Small mitre planes made by Thomas Norris followed, and they can be seen here. A full range of Norris mitre and thumb planes planes were available in the J. Buck 1912 catalogue for pianomakers.

Scottish Chariot Planes:

Scottish style chariots, from the mid-19th century, with their mouth 1/3rd of the way back from the toe, could have provided inspiration for early makers of the thumb plane.

Scottish chariot planes are characterized by having a stepped toe, front infill, flat heel, and a mouth placed 1/3rd of the way back from the toe. The iron, is usually around 1 1/4″ wide, bevel up, over a rosewood bed.

Length ranges from 4 1/2″ to 5 1/2″, proportions that were mirrored in the English thumb planes. Some examples are very high quality.

Someone opened up the mouth on this one.

James Claussen’s Scottish Chariot plane is one of the finer examples of this type of plane, with a small tote, and a nice half-round bridge in gunmetal. Scottish Chariot planes are scarce, and it is evident that these were personalized by their user/owners, in contrast to production type planes.

Years of the Thumb Planes

Working in the early to mid-19th century, George Kerr (born in Aberdeen, Scotland 1805) may have been the first innovator of thumb planes, and Stewart Spiers likely commenced making them around that same time or a few years later. John Holland also made thumb planes and his working years were 1858 to 1907. The last historical manufacturer of the thumb plane was Thomas Norris & Son (late 19th century to ~1942), and Norris made more of this type than anyone else in the trade. Thomas Norris (1836-1906) was located at 57 York St, (in Lambeth, London) and John Holland (1831-1912) worked out of 93 York Rd., and they were there concurrently between 1870 and 1890. It would have allowed plenty of time for an exchange of ideas between these two planemakers.

George Kerr Thumb Planes

Kerr thumb plane, dovetailed, closed toe with front infill. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, March, 2013.

Kerr thumb plane, 4 1/2″ x 1 3/8″ with rosewood wedge, infill, and fine mouth. No. 1093 in Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools.”

Early thumb plane, with some chariot plane features, made by George Kerr, 36 Store St., Bedford Square, London (address c. 1864 in Williams London Trade Directory). Earlier in his working life, George Kerr had been a piano action rail fabricator. This thumb plane was included in David Russell’s, Antique Woodworking Tools, no. 1093. Originally, it had a tapered 1 1/8″ Buck iron, but that got switched with 1092’s Ward iron, another Kerr thumb plane. Kerr may have had a trading relationship with George Buck, or he could have just walked around the corner to buy the iron while work was in progress on this thumb plane. No. 1092 had an open toe, and that made it appear much more like a classic thumb plane.

Same Kerr thumb plane, in the Stanley September 2015 auction. 4 1/4″ long, and 1 1/2″ wide, with mahogany wedge. No. 1092 in Russell’s “Antique Woodworking Tools.”

This dovetailed Kerr Thumb plane with open toe, sold in the David Stanley International Auction in September, 2010. It is 4 1/4″ long, and 1 1/2″ wide, with an ebony wedge (possibly a replacement).

Here is an unmarked thumb plane in gunmetal, with many Kerr features. This example has Brazilian rosewood infills, and a Ward tapered iron. The cheesehead screw strike button has a Whitworth 1/4-20 machine thread which screws into the threaded hole of the gunmetal heel, and then into the rosewood rear infill. For the 1861 U.K. Census, George Kerr declared his profession as a “Gunmetal Manufacturer.”

Kerr Thumb plane (unmarked), with enclosed toe, front and rear flanges, and hybrid Chariot/Thumb plane features.

19th century English thumb plane, dovetailed and unmarked, although it may have had a visible stamp originally. An early user tapped on the thick gunmetal bridge habitually. Professionally-made dovetails on this plane are virtually invisible, with the exception of the ones for the rear plate. The strike button at the rear (a cheesehead screw–now replaced with same) had been mightily pulverized, and probably slightly straightened the convex heel causing the dovetails to become visible there. Fortunately, the hammering did not extend into the heel itself. The Kerr thumb planes shown above, also had a separate heel plate, dovetailed to the sides. On this example, the sides were cut for trailing dovetails into the sole which was part of the reason that the rear flange was made longer than most other English thumb planes. Behind the bridge, the top edges of the sidewalls have a slight lip on the inner sides. It’s an indication that those surfaces were burnished smooth rather than filed or sanded–an old method. The infill bed, which was pinned to the sides, was also drilled out for lead weights, of the same type that would be installed in a quality piano keyboard in the factory. This was a piano plane for sure, and it most likely came out of a piano factory.

Lead weighting adds mass, and the resulting inertia makes it easier to cut cleanly through difficult grain with a small plane. This is the largest of all my English thumb planes at 5 7/8″. It is also slightly deeper than the others, as the pictures show.

Buck/Spiers Thumb Planes

Same Spiers Thumb plane, 11 years later, as consigned to Brown Antique Tool Auction, March, 2024. Photo by Brown Auctions.

Planemaker Konrad Sauer’s description of a Spiers no. 9 thumb plane in 2013:

[The Spiers no. 9 thumb plane] was a pretty amazing experience. Everything was exactly where it needed to be. There was an amazing relationship between the sneck of the iron, the top of the lever cap screw and the empty area at the front of the plane. There was a complex and deliberate relationship between these points and they all worked together to provide a very comfortable experience. I was pretty shocked and was once again reminded that simple looking, does not mean that complex design thought did not go into something. I kept this experience tucked away until the time was right.

Early Spiers No. 9 Thumb plane, with octagonal lever cap screw, and rounded nib on iron. Photo from Jim Bode Tools, c.2015.

Octagonal lever cap screws were featured on a relatively small number of early British metal planes dating from the late 1840s to the early 1860s. Planemakers who utilized the octagonal screw included George Kerr, Robert Towell, Edward Cox, and of course, Stewart Spiers.

The following Spiers Thumb Plane is very similar to this example with the octagonal screw, differing only in the details: i.e., sneck, rear screw, and lever cap thumb screw.

Spiers Thumb Plane, c. 1855-1865, view of heel and bulbous thumb screw, with profile contours below knurling.

View of the underside of the gunmetal lever cap and rosewood bed on the early c. 1855-1865 Spiers Thumb Plane. There is a slight 1/32″ depression in the middle (just visible in this image), but I would still consider it solid, when compared to Spiers’ later lever caps with a large and deep hollow area, covering most of the underside of the lever cap.

Spiers Lever Cap, from an 1840s mitre plane: underside, showing solid casting. A high spot at the leading edge was shimmed by brazing copper sheet.

The Spiers Thumb Plane shown below is unmarked, and was probably intended to be bought in and resold by one of the major London tool dealers in the mid-19th century. With the exception of the hand cut cheesehead screw into the heel–the example below has a flathead countersunk screw–this Spiers Thumb Plane is very similar to the signed example above.

Spiers No. 9 Thumb plane (unmarked) c. 1855-1865. Since there were so few makers of British thumb planes, identifying a maker is less difficult than with other planes. Photo from Jim Bode, 2018.

Buck Thumb plane/Spiers No. 9, 247 Tottenham Court Road (1867-1879). Right side. Photo from Jim Bode, 2016.

Buck Thumb plane/Spiers No. 9, 247 Tottenham Court Road (1867-1879). Left side. Photo from Jim Bode, 2016.

Buck Thumb plane/Spiers No. 9, 247 Tottenham Court Road (1867-1879). View from front–early owner struck the bronze lever cap. Photo from Jim Bode, 2016.

Buck Thumb plane/Spiers No. 9, 247 Tottenham Court Road (1867-1879). View of sole, with Ward iron. Photo from Jim Bode, 2016.

Looks like an original owner of this Buck Thumb plane tapped on the lever cap to adjust the iron. I imagine something like this being done towards the end of a long day of work under sub-optimal conditions.

Early Spiers No. 9 Thumb plane (c.1855-1865) showing some wear, and a replaced iron. Also No. 1347 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, 2013.

The following photographs of this fabulous Spiers Thumb plane (1865-1880) were taken by Mike at the Vintage Tools Shop in Melbourne, Australia, in around 2023.

Two different versions of the Spiers no. 9 thumb plane below. Example on the left seems older, with a longer lever cap, and similar to screw sided models. But this type was photographed for the 1908 catalogue. Plane on the right seems later, with features copied by Norris. Similar examples have shown up with Buck 247 Tottenham Ct. Rd. (1867-1879), however.

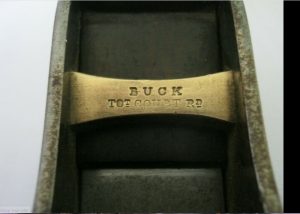

Two nibbed or snecked plane irons, Ward & Payne on left, and rare Scottish style rounded nib on iron marked “Buck Tottm. Ct. Rd.”

Spiers no. 9 thumb plane, with squared off sole, sloping sides at toe, long lever cap, and large lever cap screw.

In the 1908 Spiers’ catalogue, the no. 9 thumb plane was not in production and only made upon special order. Possibly, this was an image of an older plane that happened to be handy when the catalogue was put together.

The Spiers Thumb Plane on the right, is the version that Thomas Norris copied for their own production. While Spiers retained the same basic shape for these three Thumb Plane variations, the leading edges of the sidewalls are all different, as well as the shapes of the soles at the toes, and the extent of curvatures at the heels. Also, the lever caps are all different as well as the thumbscrews. And the nibs/snecks on the iron all have different designs.

Range of three variations of Spiers Thumb planes: l. to r.: c. 1855-1865; c. 1865-1880; c. 1865-1895.

Three Spiers Thumb planes, showing differing contours around the heels. Two Ward, and one Buck iron.

Buck/Holland Thumb Plane

Holland made planes at 68 Oakley St, Lambeth (1861-1870), then 93 York Rd. (1870-1890). Holland took over the business of metal planemaker Charles Badger (at 93 York Rd. in 1869-70) in 1870. Thomas Norris worked down the street, at 57 York St., Lambeth London.

Note the similarity with the wedge in the Holland thumb plane. I am not aware of any Badger made thumb planes.

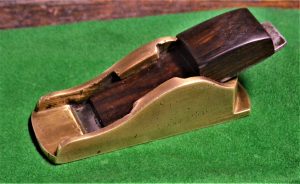

This view of the heel shows a distinct arris, which emulated the convex rear plate found on the earlier Kerr type of dovetailed thumb planes. In this example, the body was cast in gunmetal and not made of joined body components.

Reasons why I think Holland made this thumb plane: 1. Side profile similar to other Holland thumb planes. 2. Influence of Badger in the wedge. 3. Early use of gunmetal in a thumb plane. 4. Buck iron points to a working relationship, which Holland had with Buck.

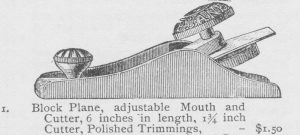

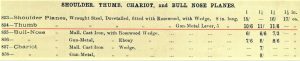

American Block Planes

American block planes were the closest domestic equivalent to the English thumb plane, but their general introduction circa 1872 postdated the thumb planes by at least 20 years. Birdsill Holly of Seneca, New York did produce a ‘block plane’ in the 1850s, but very few were made, nowhere near the economies of scale that typically exemplified American industrial production. At 7 3/4″ long with a 1 3/4″ iron, the Holly block plane was close to the size of a mitre plane. English influence from the thumb plane on Leonard Bailey was apparent in the side profile of his Excelsior pattern block plane.

Bailey’s block plane was the American version of a small plane, with a bevel up iron, set at a low ~20 degree angle. Block planes were used for end grain, but also for a myriad of general handyman tasks. –A tool for the masses. English thumb planes would more often be found in a cabinet or instrument makers’ toolkit, and used for critical detailed work.

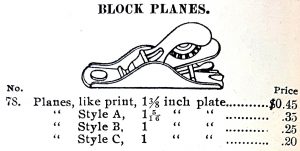

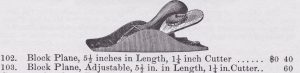

In contrast to the British thumb planes, the Bailey/Stanley block planes caught on like wildfire, and were made in prolific quantities and variations from the 1870s until World War Two. On average, American block planes ranged from 6 to 7 inches long, compared with British thumb planes, generally around 5 inches long. While similarities existed between these two types, differences were also present: thumb planes had a much thicker iron on a wooden infill bed, and they were largely a handmade product. American block planes were mass produced: much less expensive, in many cases adjustable, and had a thinner iron bedded on the iron casting.

Some five inch American block planes:

Instrument makers had little choice for a plane in the 5 inch class in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These small block planes were used for such tasks as making guitar fingerboards, stringed instrument bows, and paring down gussets on repaired piano keysticks. C. H. Lang included the Stanley no. 103 block plane in his 1905 piano supply catalogue.

Many English variants of the 102 type were made by Record, Hobbies, and Stanley U.K.

Stanley’s No. 203 plane had a casting that was only 5 1/2″ long, but because of the fittings on it, it takes up more space than the other 5″ planes shown here. The rosewood knob is oversized, the cam lock lever cap is large, and the adjustment knob extends out the back. Additionally, it looks to actually have a bedding angle slightly higher than 20 degrees. Taking that into account, it is a quality plane, with a convenient handy-grip feature, and an effective Traut iron adjuster.

Stanley No. 206 block plane, with “SW” iron, cast iron adjusting wheel, and Brazilian rosewood knob, circa 1920s.

Mathiesen Thumb Planes

Mathieson dovetailed Thumb planes with 1 1/4″ irons at 11/6, were the same price in 1899 as later Norris Thumb planes at 11/6 in 1908. At 11/- , in 1909, Spiers No. 9 Thumb planes were less expensive, and in Norris’ 1914 catalogue, prices for their Nos. 31 and 32 Thumb planes were reduced to 11/-. and 10/6 respectively.

Mathieson No. 854 thumb plane, as illustrated in their 1899 catalogue. Profile was weighted towards the closed heel, and appeared much like a Norris no. 12 dovetailed thumb plane.

Reproduction of the same model Mathieson thumb plane by Bill Carter. General shape is more symmetrical than the classic British pattern thumb plane. Photo from infill-planes.com

The interesting and highly valuated Mathieson thumb plane sold in the November 2019 Brown Tool Auction for $4,746.00 (before commission). We are unlikely to see another one come to market anytime soon. Noted collector, George Anderson, wrote that the thumb plane, in general, was the most challenging of all the British infill planes to collect.

George Anderson’s impressive collection of English and Scottish thumb planes. Photo by George Anderson, March, 2022.

Carter Thumb plane, made after early Mathieson. David Barron added an overstuffed aged boxwood front infill. Photo by David Barron, 2012.

A graphic lineup of lever cap screws and a variety of knurling patterns. Spiers on the two outside planes, and Norris on the two in the middle. Photo and planes from the collection of George Anderson.

Adding an overstuffed infill above curved siderails like this is a task involving some careful fitting.

Below are two Carter/Mathieson Thumb planes with front infills done by Bill Carter. He has made the side rails less curved for the over-stuffing. Photos by Bill Carter.

Buck/Norris Thumb Planes

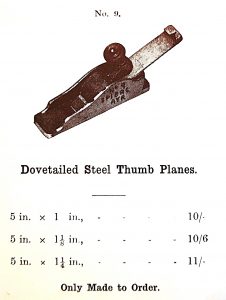

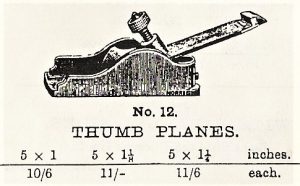

Thomas Norris’ first thumb planes were dovetailed and were classified as No. 12. These were not produced in any quantity, but some of them were rebadged as Buck thumb planes. While the dovetails are not visible in this image, the iron shows a nib, which was not present in the 1914 and 1928 catalogues. Norris’ No. 31 Thumb plane, in the 1928 catalogue, did show a rebate style sneck on both sides of the iron.

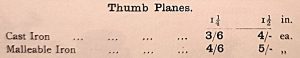

J. Buck 1912 Catalogue: Norris Thumb planes for 10/0 (No. 32) and 11/0 (No. 31). Thumb plane with wedge for 6/6 was another make, probably unmarked.

In July 2020, an example of a Buck/Norris No. 12 thumb plane came to market on Ebay U.K. Here are some photos of that plane (please excuse photo quality). In the 1908 Norris catalogue, the no. 12 was included, but by the time of the 1914 Norris catalogue, the no. 12 was replaced by the nos. 31 and 32. These pictures reveal, however faintly, the dovetailed construction of the Norris (Buck) no. 12 thumb plane. The front infill differs from the later no. 32 Norris thumb planes, and the toe is shortened, not unlike some of the Mathieson thumb planes.

Before the 1914 catalogue, Norris started making their thumb planes with cast “Patent Metal,” or “Unbreakable.” Photo from Ebay, 2016.

“Unbreakable?” Do not believe everything that you read.

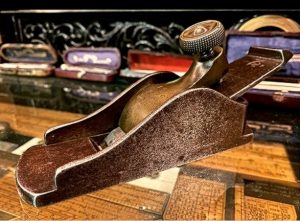

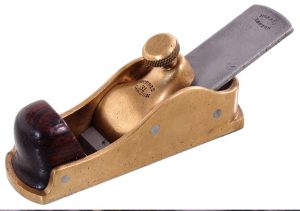

Two Norris thumb planes, with thick 1 1/4″ parallel irons, bright ground and marked “Buck Tot. Ct. Rd.” Both planes marked and sold by Buck. In the foreground is no. 32, and in the background is no. 31. The two examples were made in the early 20th century, and depicted in the Norris 1914 catalogue.

“The Metal Thumb Plane, English type …is 5 in. long, and …1 1/4 in. wide [cutter]; it has a long cutter, which answers for a handle, and is secured with a gun-metal screw lever. It is, I believe, a specialty of Mr. George Buck, whose address will be found in the advertisement pages of this book.”From “Modern Practical Joinery,” by George Ellis, 1908.

This plane iron with the mark “Buck Tottm. Ct. Rd.” has been found on a Kerr thumb plane as well as a Holland thumb plane. The iron on the left appears to be a parallel iron, while the iron pictured with the Holland thumb plane is tapered. Other Buck stamps on Buck thumb plane irons are smaller and more subtle.

The Norris No. 31 in gunmetal, and the No. 32 in malleable iron were sold in the Martin Donnelly November 2020 Tool Auction. Photos by MJD Antique Tool Auctions.

Two Norris No. 31 planes are shown below, in gunmetal, but without the front bun, which may have been the way the No. 31 was available when the gunmetal casting was first introduced–and then the rosewood infill at the toe was added some months later. A clue in ascertaining this chronology is the use of an earlier Norris knurling pattern on the lever cap screws; this is the same pattern, set at 90 degrees, as what was used on the No. 31 models with a malleable iron casting. Not to be ruled out entirely though, the gunmetal No. 31 without the front infill could have been a custom order. Norris continued to offer custom made planes as late as the Rebate Mitre plane in 1941.

Norris No. 31 Thumb plane, in gunmetal, without front bun. Photo by D. Stanley Auctions, September, 2014.

Norris No. 31 gunmetal thumb plane, late 1920s-early 1930s. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, September 2016.

Norris No 31 gunmetal thumb plane, mid to late 1930s. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, September 2021.

Norris 31, in steel soled gunmetal and front infill. By Norris’ 1928 catalogue, this was how No. 31 was offered, rather than in “patent metal,” cusped lever cap screw, and open toe.

“…Certainly some of these planes, most notably Norris thumb planes, were marketed towards pianoforte case makers and the like.” –C.R. Miller, infill.planes.com

The Norris No. 31 gunmetal thumb plane shown above is a very late model. Following details of this No. 31 thumb plane substantiate the assertion:

- Lever cap shortened in front of the fulcrum (more of the iron exposed immediately behind the bevel).

- Lever cap screw knurled in a general diamond pattern rather than the traditional Norris pattern in rows.

- Stamp on lever cap: lettering without serifs.

- Stamp on iron: lettering without serifs, (generally but not absolutely) indicating late 1930s production. Postwar Norris irons also had a stamp with lettering without serifs, but Norris Thumb planes were not made post WWII.

- Sweated-on steel sole in 1 piece–rather than 2 used earlier, with the rear steel sole piece pinned to the gunmetal casting. Pinning was done to prevent separation. Utilizing the 1 piece applied steel sole on the late Norris thumb plane was a shortcut. Here is another example of this late version of the Norris No. 31 thumb plane:

This plane iron, shown on the right, has machining marks typical of those found on some c. 1930s Sheffield plane iron.

Line-up of Norris No. 31 Thumb planes l. to r.: iron casting, nib, and finial on lever cap screw; gunmetal casting, later diagonal knurling in rows, and two piece sole (small mouth); gunmetal casting, smaller lever cap, generic knurling, and 1 piece sole.

When this late Norris No. 31 Thumb plane was made, it was stamped “31” in the bed, and was probably the only 31 in the batch of planes being made at that time in the Norris New Malden workshop. Therefore, only the model number “31” was needed to identify this solid mahogany part. At this late date, care was still taken to make the bed fit to the inner casting.

Norris’ No A31 replaced the standard No. 31 in the c. 1930 catalogue, but in practice, the 1930s details of the actual planes point to both models having been produced during the same time period.

A late Norris No. 32 Thumb Plane in gunmetal, as sold in the Brown International Auction, October, 2023.

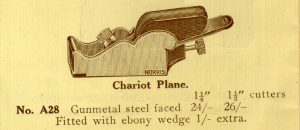

Norris No. 32 Thumb planes were offered in steel-faced gunmetal in their 1928 catalogue, for 26 shillings, the same price as Norris’ No. 31 Thumb planes with lever cap. By 1930, the A31 Adjustable Thumb plane was offered for just a little more, at 28 shillings. In the 1914 Norris catalogue, No. 32 was 10/6, and No. 31 was 11. Around the late 1920s, early 1930s, Norris’ No. 32 thumb plane was no longer a less expensive option. And by this time, a new plane coming to market utilizing a wedge and bridge was becoming increasingly anachronistic. Customer demand was reduced. Because of this, very few gunmetal Norris No. 32 Thumb planes were made, and examples are exceedingly rare.

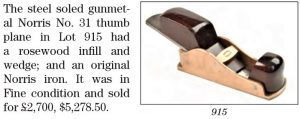

Norris No. 32 Thumb plane in gunmetal with steel sole. Image and text from MWTCA “Gristmill,” December 2014. Review of March. 2014 D. Stanley Auction in the U.K. by the late John G. Wells of Berkeley, CA.

Photo of the same gunmetal no. 32 Thumb plane shown on the left. Photo by D. Stanley Auctions, March, 2014.

That’s $5,278.50 before commission and tax. After tax and commission, the price would have approximated $6,440.00.

Shown below, is a gunmetal Norris No. 32 Thumb Plane that sold in the David Stanley May 2024 Antique Tool Auction. Despite the fact that the rosewood was exposed to prolonged sunlight (UV), the plane itself was in very good condition.

A gunmetal Norris No. 32 appeared on the catalogue cover of a David Stanley International Auction in 1993. Apparently, it was in mint condition, and also included was the original Norris box from the 1930s.

The late No. 32 had a bridge with convex sides, instead of the concave sides in the earlier version. This convex bridge was similar, but not identical, to the bridges on the A31 Thumb planes and the Gunmetal No. 28 Chariot planes.

Shown below is a version of the early Norris No. 32 in “Patent Metal,” which never had a front bun; there are no traces of one, and there are no rivet holes through the sides at the toe. There are other examples of the Norris 32 in malleable iron without the bun: for example, no. 1261 in “Antique Woodworking Tools,” by David Russell (p. 420).

This early dovetailed thumb plane has a separate heel plate, and the Norris No. 31 is cast gunmetal. The Spiers No. 9 Thumb planes typically have a U-shaped bend at the back, and no separate heel.

The Norris A31 was not just a No. 31 with the infill bed mortised and an adjuster dropped in. The gunmetal casting is 3/32″ wider than the no. 31 shown above, and 1/16 wider than my no. 32 thumb planes. Standard alterations include an open heel, with protruding boat stern shape; adjustment thumbscrew with #11526 patent inscribed; “Norris London” marked bridge with convex edges; the bridge thumbscrew is indented, for finger placement, not unlike a Stanley 102 block plane. The mouth on the A31s were generally tighter than the late 31s.

Norris No. A31 Thumb plane, showing adjuster, and modified wedge and iron. Photo from Norrisplanes.com

Some Norris A31 Thumb planes had mahogany infills rather than rosewood, which altered the overall appearance of the tool. The front bun looks as if it may have been stained at one time (photo on the left). Both images below have the “A31” mark missing from the wedge.

Norris No. A31 Thumb plane, with what appears to be opaque-stained mahogany. Photo from Brown Tool Auctions, 2021.

Here you can see Norris’ second patent No. 11526 dated 22 June, 1923, for the adjustable iron feature which enables fore and aft adjustments as well as lateral motions with one knob. The Spiers thumb plane has a full Ward iron with a nib or sneck.

Related: Norris Chariot planes

Between 1914 and 1936, Thomas Norris continued producing specialist planes, while other known makers, such as Spiers, discontinued them (except Coopers’ Plucker). Only Norris kept alive the traditional chariot, mitre, and thumb planes during this period.

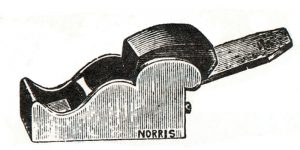

Norris no. 28 chariot plane as it appeared in the 1914 Norris catalogue. Image from norrisplanes.com

John William Mitchell was a British dealer at 94 Newington Causeway, London between 1865 and 1910. Norris’ “Patent Metal” was stamped on bridge. Most chariot planes were the bullnose type, like this one, with the mouth at the toe of the sole. Also, chariots were shorter ~3 1/2″ and blockier than thumb planes.

.

Thomas Norris Jr.’s decision to continue making violin, chariot, thumb, and mitre planes after the Great War was conceivably informed by his grandfather Thomas Norris (1804-1886), who was a music engraver. Music engraving was a prime example of the craft side of music. And so was instrument making. Violin, chariot, thumb, and mitre forms of planes were inextricably linked with the luthier’s tradecraft and piano manufacturing.

Unmarked Thumb Planes

This thumb plane (right) may be cast iron or dovetailed. It has an extra large lever cap, and a thumbscrew that looks a bit like early Spiers, or possibly Holland. A mystery that may never be solved.

Unmarked thumb plane, no visible dovetails (may or may not be present). Possibly Spiers or Holland. Photo from David Stanley Auctions, March 2016.

Dovetailed brass thumb plane, with shape like a Scottish chariot plane at the heel, and infill like a Norris Thumb plane at the toe. Photo from Summersgills Auction, 2017.

The Thumb/Chariot plane show below has a pattern identical to some Irish Chariot planes, but it has been scaled down to 4″ long. Typically, Irish Chariot planes range from 6″ to 8″ long. Also, this small plane has a rosewood infill bed; infilling the bed is more commonly done on Thumb planes, and Irish Chariot plane castings are usually finished off without adding a wooden infill for bedding the iron. The inclusion of a rosewood infill bed was a positive commentary on the overall quality of this plane.

While this Scottish chariot plane lacks a stepped toe, the rest of the plane conforms to this category. A significant portion of Scottish chariot planes were made with a half round rosewood or mahogany bridge.

Unmarked Thumb plane with no visible dovetails in photographs. Probably a Norris No. 31 c. 1910. Photo from Tooltique, c. 2017.

Sole of unmarked thumb plane with Fletcher Leader St. Chelsea iron. Fletcher, a toolmaker and dealer, probably sold this plane. Photo from Tooltique, c. 2017.

This gunmetal thumb plane has a flat heel like a chariot plane, but in all other respects, it has a thumb plane design. It is simple yet elegant.

With the bronze heel of this English Thumb plane 5/8 inch thick at the center, this is a heavy plane for its size. The use of lugs instead of a bridge as well as the use of gunmetal suggest a maker such as Badger or Holland. Since there are no other clues that are apparent to me at this time, I would conclude just as easily that it was craftsman made.

H. stands for heavy!

Not to be outdone, the maker of this Thumb/Chariot plane intercross shown below on the right, filled the bed with molten lead, and then filed it flush. Hopefully using precautions.

The following craftsman made English Thumb plane was found with a 3/32″ steel rod for a bridge. I took the liberty of modifying it, using offcuts of kingwood from a larger project. I added an overstuffed front infill, a Buck type bridge (curved, with Cupid’s Bow), with 3/16″ steel rod, and a rounded nib on the iron for adjustment. The one-off gunmetal casting is completely solid from the rear edge of the mouth to the edge of the heel. The concept of making these English Thumb planes as heavy as possible appears to have been put into relatively common practice. As common as thumb planes are, anyway.

English gunmetal Thumb plane, with overstuffed front infill, Buck type bridge with Cupid’s Bow, luthier style wedge, and Scottish style rounded nib on iron.

Normally, I would not alter an antique tool, but in this case, the plane was made as a one-off casting, and I tried to extend the craftsman modifications in the period style.

The entire casting behind the mouth, is solid bronze! Unidentified iron has anchor and “S” stamp. I don’t believe it was the “Anchor Brand” made by Jernbolaget of Eskilstuna, Sweden; it might be a mark connected with ship building, that is just a guess.