- © 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

STEWART SPIERS MITRE PLANES

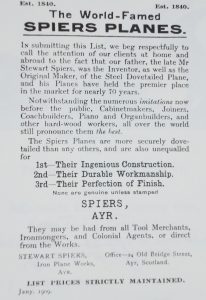

“…Piano and Organbuilders, and other hardwood workers, all over the world still pronounce [Spiers planes] the best.” It goes without saying that Spiers was not the inventor of the dovetailed plane. When you make the distinction of an all ‘steel dovetailed plane,’ however, there’s a greater chance that it is true.

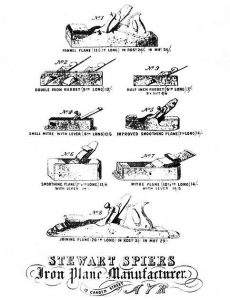

Stewart Spiers (1820-1899) made his planes in Ayr, Scotland, on the west coast. Spiers played a major role in developing and popularizing wood infilled metal planes, including panel, smoothing, thumb, shoulder, chariot, and improved mitres. Although, its fair to state that Spiers was not necessarily the original inventor of these forms, with the possible exception of the improved mitre plane. For a thorough examination of Stewart Spiers, his business, life, and family, I recommend “Through Much Tribulation: Stewart Spiers and the Planemakers of Ayr,” by Nigel Lampert.

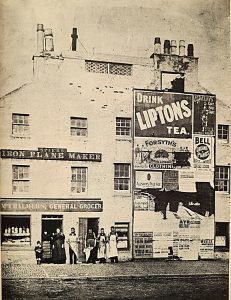

Stewart Spiers’ Workshop was located on the western corner of the intersection at Garden St. and River St. Burns’ Tavern is still in business next door.

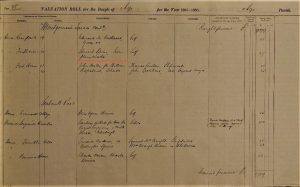

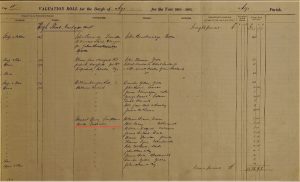

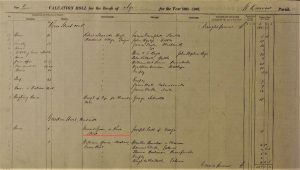

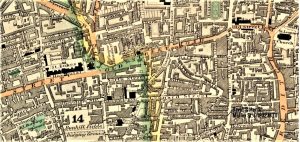

Section of Ayr, Scotland, from the 1855 Ordnance Survey. Garden St. and River St. are the places where Stewart Spiers spent his working life. Stewart took over his father William’s unnumbered River St. shop in 1844, after he died. Stewart produced some of his early planes at 12 Garden St., c. 1851-58. In 1858, Stewart moved his shop to 3-4, 5, and 11 River St., where he remained until his death in 1899. I’ve included the following Ayrshire documents to clarify Stewart Spiers’ early locations.

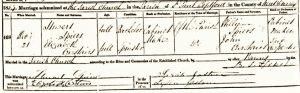

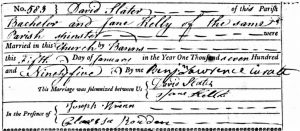

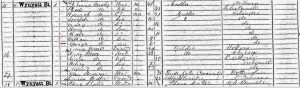

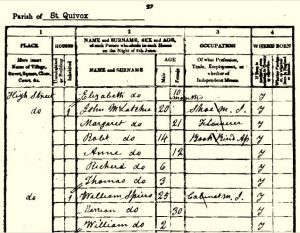

On 11 June, 1807 William Speir (Stewart’s father) married Jane Stewart at St Quivox and Newton, Ayr. Stewart Speir, the 7th of 9 children by this couple, was born 2 October, 1820.

The Spiers family were secessionist Christians, who broke away from the Church of Scotland, most likely belonging to the Free Church of Scotland. A strong Protestant work ethic was instilled upon Stewart from a young age. The Spiers family gravestone is located in the Wallacetown Secessionist Cemetery.

In around 1835, when Stewart Spiers turned 15, he would have started his apprenticeship with his father William in the family business of cabinetmaking. Being known as a bright person, Stewart would have picked up his father’s cabinetmaking skills rather quickly.

Entry for Stewart Speirs, in “Universal Dictionary of Violinmakers and Bowmakers,” by William Henley (1874-1957) Despite inaccuracies, at least one Spiers violin was recorded with a date of 1862 on the label.

A skilled amateur violinist, Stewart played with the Ayr Musical Association during the 1850s, which later merged with the Ayr Choral Union. Also, Spiers made a limited number of violins. Author Henley often weighed in heavily with his opinions about the violins.

From “British Violin-Makers, Classical and Modern; being a Biographical and Critical Dictionary of British makers of the Violin from the Foundation of the Classical School to the End of the Nineteenth Century,” by William Meredith Morris, 1904.

Spiers received a better review from Morris in 1904. With either Henley or Morris, though, it’s difficult to determine how many examples they based their assessments on.

Remarkably, Stewart Spiers never made luthier planes, despite the fact that he both played and handcrafted violins. Spiers’ competitor and emulator, Thomas Norris would go on on to make a fair quantity of instrument makers’ planes.

The 1830 McCarter’s Ayrshire City Directory listed William Speir, Cabinetmaker, at 12 Garden St., Ayr. By 1837, Pigot’s Ayrshire City Directory listed William Speir, Cabinetmaker, at River Street. Subsequent Ayr City Directories revealed that the Spiers family retained their [12] Garden St. address through the 1830s, and into the early 1840s. William Spiers must have been doing well enough to afford renting a workshop outside of his 12 Garden St. home.

Wallacetown (named for William Wallace, 1270-1305) was a section of the city of Ayr, housing many craftworkers, and immigrants from Ireland. Wallacetown was also referenced in Spiers’ 1851 Scottish U.K. Census entry, as well as in the Ayrshire Valuation Roles for 1875, shown further down this page. The following quote regarding Wallacetown came from “A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland,” by S. Lewis (British History Online), originally published in 1846:

WALLACETOWN, lately a quoad sacra district, in the parish of St. Quivox, district of Kyle, county of Ayr; containing 4620 inhabitants. This is wholly a town district, and formed of the villages of Wallace and Content, which adjoin the burgh of Newton-upon-Ayr, on the east side, and are separated from Ayr by the Ayr river, over which is the handsome structure at this place, called the Bridge of Ayr.

The villages are built on the lands of Sir Thomas Wallace, of Craigie, and have arisen since the year 1760, in consequence of the establishment of coal-works in the immediate neighbourhood, and of the increase of manufactures in this part of the country. They consist of indifferent houses, inhabited chiefly by persons engaged in the mines and in weaving, and by agricultural labourers, and artisans in various handicraft trades: the weavers work at their own houses for the manufacturers of Paisley and Glasgow. From the moderate rents, and consequent cheapness of lodgings, numerous of the labouring classes from Ireland have settled here permanently, and many more make it a place of temporary abode.

Owing to this district of the parish being by far the most populous part of it, a chapel was erected by subscription in 1835, at a cost of £1550; in the following year it became an independent church, and Wallacetown was then constituted a parish in itself, so far as respected ecclesiastical affairs. It is in the presbytery of Ayr and synod of Glasgow and Ayr, and the patronage is vested in the male communicants: the stipend of the minister is £150, derived from seat-rents and collections, but there is neither manse nor glebe. The church is a neat and substantial edifice, adapted for a congregation of 865 persons, thirty seats being free. There are also places of worship for members of the United Secession, Antiburghers, Reformed Presbyterians, and a congregation of Independents; and a Roman Catholic chapel. In the united villages are likewise six schools.

The Independent Chapel was located on River St., and can be seen on the map shown above.

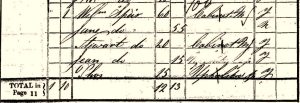

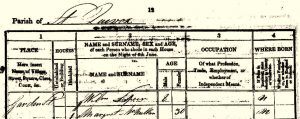

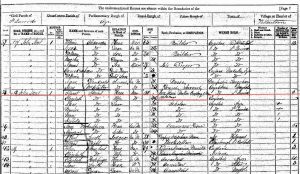

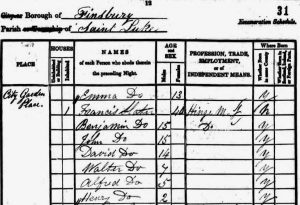

In 1841, William Speir, age 60 (1778-1844), “Cabinetmaker J[ourneyman],” was recorded in the Scottish U.K. Census as living at [12] Garden St. The following Speir family members were also living there: Jane Speir, age 55; Stewart Speir, “Cabinetmaker J[ourneyman],” age 20; Jean Speir, age 15, “Upholstery apprentice”; Thomas Speir, age 15 “Upholstery apprentice”; William Speir, age 8 [nephew].

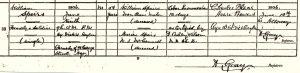

William Speir, 60, and Stewart Speir, 20, “Cabinetmaker J[ourneymen]” living at [12] Garden St. Wallacetown, Ayr. 1841 Scottish U.K. Census

William Speir, 8, son of Alexander (oldest son of William Sr.) living at [12] Garden St. Wallacetown, Ayr. 1841 Scottish U.K. Census.

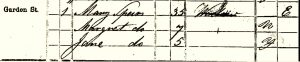

Mary Young Speirs was also living on Garden St., but in a separate unit. Her husband Alexander died on 8 April, 1837, in the U.S.A.

William Spiers. Wright (maker or builder). Stewart’s older brother, born 1812. 1845 Ayr P.O. Directory. William Spiers Sr. died in 1844.

Ayr 1851 P.O. Directory. Stewart Spiers was now producing cabinet making and plane making work out of [12] Garden St.

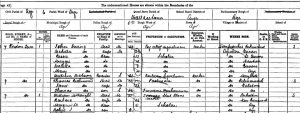

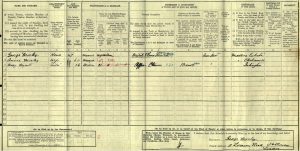

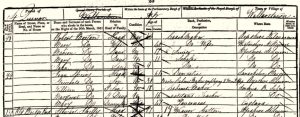

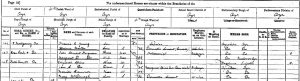

Stewart Speirs, “Master Cabinetmaker, Employing 2 men & 2 Apprentices. [3-4] River St., Wallacetown, Ayr. From 1851 Scottish U.K. Census.

In the 1851 Scottish U.K. Census, Stewart Speirs, age 30, “Master Cabinet Maker, Employs 2 Men & 2 Apprentices,” was living on [3-4] River Street, with the following family members: Jane Speirs, 64, mother, head; Stewart, 30, son; Margaret Speirs, 16, granddaughter; William Speirs, 18, grandson; Mary, 47, daughter in law.

Stewart Spiers visited the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851.

Spiers had London connections, as a number of his planes were rebadged by Buck, Moseley, and Archer, among other tool dealers. Spiers also sent a number of his early planes to the United States.

“Mr. Spiers visited the London Exhibition of 1851 and on passing through the Crystal Palace, was interested in seeing an iron plane exhibit, which greatly to his surprise, embraced a number of his own planes set out on view. “Where did these come from?” asked the maker of them. “From America,” replied the attendant. “Indeed” said Mr. Spiers, “and who made them?” “Why Spire” said the man, “Haven’t you heard of Spire?” It turned out that the planes were a lot that he sent to America.”

–Maria Carstairs Spiers, The Ayrshire Post, 21 May, 1937.

Stewart Spiers lived in Deptford, London probably for a few months per year, for a couple of years. This was done in an effort to build relationships with tool dealers for the purpose of establishing and expanding Spiers’ market for his planes in the Greater London Area. Apparently reasonably successful early on, Stewart Spiers was able to maintain the rent for 12 Garden St., 4 River St. and 2 Newbridge St., in Ayr, while staying in Deptford during this time. It would be sensible to assume that Stewart received a family discount rental rate from his mother, Jane Stewart Spiers, for 12 Garden St., and 4 River St.

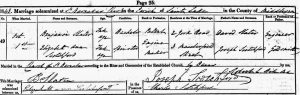

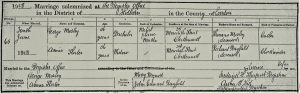

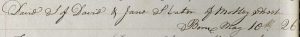

Stewart Spiers married Elizabeth Carstairs, at the parish of St. Quivox, in Ayr, Scotland, on 3 December, 1854.

Jane Stewart, the first child of Elizabeth and Stewart, was born on 20 November, 1855, in Ayr, Scotland.

Birth record for Jane Stewart Spiers, born in Ayr, on 20 November 1855. Stewart and Elizabeth Spiers lived at 2 Newbridge St., Ayr.

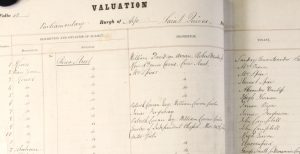

Ayrshire Valuation Rolls for 1855-1856 showed Jane Stewart Spiers (1788-1874) living at 3 River St., and Stewart Spiers living at 4 River St.

Jane Spiers was the owner of houses at 3,4,5,and 6 River St. 11 River St. was occupied by Hugh Sirvan.

It has been generally understood that Stewart Spiers’ River St. workshop (c. 1857-1899) was not the same building as that of his father William’s Workshop (c.<1837-1844) but I could find no evidence to to rule out that possibility, either. As you can see in the Spiers timeline laid out here, there was a definite pattern of Stewart occupying his parents’ former properties, which was a universal practice. Specific street number information, sketchy and inconsistent throughout the 19th century in Ayrshire and elsewhere, was even more so before c. 1845.

Stewart Spiers, 40, “Cabinet & Iron Plane Maker,” and Jane Spiers, 75, “Landed Proprietor,” at 18 John St., in the Scottish U.K. Census for 1861.

Stewart’s mother Jane Stewart Spiers, at 75, continued to hold ownership of the family properties. “Landed Proprietor” was a 19th century term, meaning landlord, or deriving income from owned land and/or properties.

Ayrshire Valuation Rolls in 1865 for Stewart Spiers, “proprietor“: 1 River St., part owner; 3 River St. Workshop/Office, partner with Jane Spiers; 4 River St. Workshop, partner with Jane Spiers; 20 [12] Garden St. House. partner with Jane Spiers.

Between 1856 and 1865, Stewart Spiers went from tenant, to owner of several properties. This was a period of maturation and upward mobility for Stewart.

As you can see street renumberings (if numbered at all) were quite an issue then, and for the researcher now. 20 Garden St. was most likely formerly 12 Garden St.

In 1865, the proprietors at 11 River St. were “Managers of the Independent Church” (see River St. map at top of page)

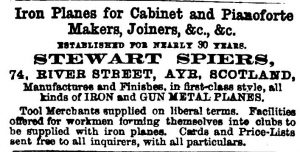

“Tool Merchants supplied on liberal terms. Facilities offered for workmen forming themselves into clubs to be supplied with iron planes. Cards and Price-Lists sent free to all inquirers, with all particulars.” An interesting proposition! This is the first time I’ve seen 74 as a street number for the Spiers workshop on River Street.

Stewart Spiers 1867 Ayrshire P.O. Directory. First listing of “Iron Planemaker” without “Cabinetmaker.”

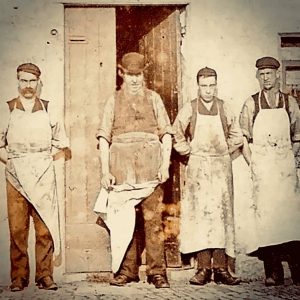

Photo of Spiers’ staff, c. 1890s. 1871 U.K. Census: “Employs 1 man and 2 boys.” From collection of George Anderson. Thank you George!

Stewart Spiers, in the 1871 Scotland census. “Iron Plane Maker Employs 1 man and 2 boys.” House at 18 John St., Ayr.

Spiers’ employees in the 1871 census matched the photo taken of his crew some 20 years later.

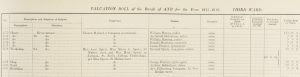

1875 Ayrshire Valuation Roll: Stewart Spiers shared 3-4 River St. with his brother William Spiers, and 1 River St. with 2 business associates.

- 3-4 River St.. 1857-1876.

- 5 River St., 1876-1884 (possibly a move; Jane Spiers owned 3, 4, 5, and 6 River St. in 1855).

- 11 River St., 1885-1894

- 10 River St., 1895-1899

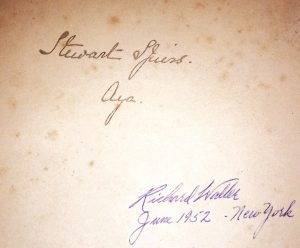

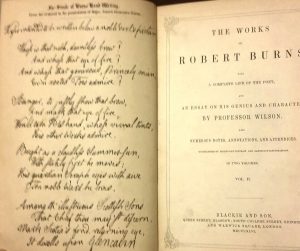

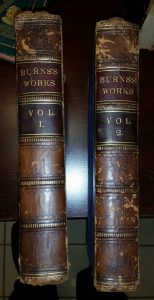

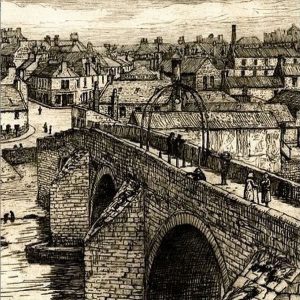

From 1855 to c.1876, 3 River St. was next door to 2 River St., Robert Burns Tavern, which is still in business today as The Burns Pub. Stewart Spiers had more than a neighborly interest in Burns; he signed his personal copy of The Works Of Robert Burns; Illustrated By An Extensive Series of Portraits and Authentic Views With A Complete Life Of The Poet; An Essay On His Genius and Character 2 Volumes, published by Blackie & Son, Glasgow, 1846.

In the 1885 Ayr Valuation Roll, the Tavern was changed from No. 2 to No. 7 River St., and Robert Burns Tavern was still next door to Spiers’ properties, which were renumbered to 9 and 11 River St. With the possible exception of the Spiers Workshop at 5 River St, c.1876-1884, the change in Spiers’ River St. addresses were renumberings rather than actual moves.

After the death of their mother, Jane Stewart Spiers in 1874, ownership of the family properties on Garden St. and River St. were split between William and Stewart Spiers.

Stewart Spiers, “Iron Plane Manufacturer, “5 River St., house, Firth View, Fort. 1876-1877 Ayrshire City Directory.

Stewart Spiers, 60, “Iron Plane Maker,” at Sea Bank Rd., Fort [Firth View], in the Scottish U.K.Census for 1881. Elizabeth Spiers, 60, wife; Jane Spiers, 25, daughter; Mary Spiers, 21, daughter; Isabella Spiers, 18, daughter, Mary Smith, 17, servant.

Firth View, Seabank Rd., Montgomerie Terrace. Stewart Spiers’ dream home, c.1874-1905. Photo from Google maps.

Taxation records can often show more information than City Directories regarding the activity of an historical figure, and that is the case with Iron Planemaker, Stewart Spiers. Shown below is an 1885 snapshot in time of Stewart Spiers business during the pinnacle of his business activities. As expected, Spiers’ house and workshop, Firth View and 11 River St. were included, but Spiers was also a landlord of 11 tenants at 176 High St., and a landlord of Joseph Scott at 1 [12] Garden St. Stewart’s brother, William was living at 178 High St., probably the same building, in 1841 (census) through at least 1845 (directory).

Politically, Stewart Spiers was progressive, and he belonged to the Liberal Party.

Stewart Spiers, 70, retired, and “Ella” [Isabella] Spiers, “Iron Plane Maker,” Firth House [View], in the Scottish U.K. Census for 1891.

Valuation Roll, on River St, Ayrshire, in 1895. Stewart Spiers, “Iron Plane Maker.” was renting out No. 9 River St. as James Chalmers’ grocery store, and using No. 10 River St. as his Workshop. No.11 River St. was rented out by Spiers for “hoarding” (warehousing/advertising).

A small sign on the corner of 11 River St., reads “Garden St.” Viewed from the corner, you can see the size and scope of this building, which has a 35′ frontage. The top two floors, at least, have low ceilings, and the overall layout is quite compact. At 7 River St., is The Burns Pub, which has been next door, with varying street numbers, since before 1855.

It was not outside the realm of possibility that this building (or the original structure to the left side) was occupied earlier by Stewart’s father, William Speir (1787-1844) between <1837 and 1844.

Spiers’ Traditional Mitre Planes

Several features indicate that this original pattern mitre was made between the 1850s and 1870. These include a flying saucer-shaped or domed lever cap screw, tapered iron, lack of sole extension at the heel, and side screws to secure the lever cap. Also, the sidewalls at the heel form one large horseshoe bend with two curved dovetails. It does not have the earliest version lever cap, with the long narrow neck; this lever cap was made to be more robust.

The lever cap neck is very long and slender. Spiers later discovered that the lever cap does not need to be so long for sufficient leverage with holding down the iron securely. In fact, later Spiers planes have much shorter lever caps. An example of a very short Spiers lever cap can be seen on an improved pattern Spiers mitre plane further down this page. Body of the plane is fairly similar to the later Spiers mitre shown above.

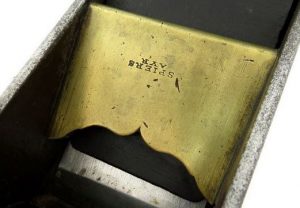

This Spiers mitre plane is old enough to have the front and rear sole dovetailed together (at the mouth) rather a simpler diagonal butt joint which was employed later. In general, an upside down stamp on the lever cap does not necessarily indicate early manufacture. The pinned infills, snecked iron without dog-eared corners, rear sole extension, and larger diameter of threads on lever cap screw suggest later manufacture. Also, the sidewalls at the heel have two bends, or rounded corners, rather than one large horseshoe bend with curved dovetails, as featured in the earlier full sized mitres. Front infill has a longer top than the earlier style, and a simple concave shape under the lip, at the back, compared to a long exposed ogee on the earlier mitre infills. Later in the 1890s, Spiers changed the lever cap screw to a plain unadorned domed shape.

Three Spiers mitre planes together. Here you can see the evolution of Spiers’ traditional mitre plane with lever caps. Quality was steady throughout, but planes became more practical in use, with the passage of time.

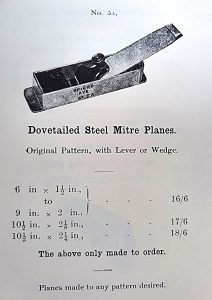

By this time, Spiers’ box mitre was no longer in regular production, but available by special order. Note that the catalogue image show a cusped lever cap screw, but actual examples in 1909 would have been a flat-topped screw.

Spiers small mitre plane with lever cap, from Garden Street price list. Note the double bend and flange at the heel: small early Spiers mitres tended to have that, while early full sized Spiers mitres did not.

Spiers mitre plane, with traditional wedge, pinned later style infills, small Spiers inscription right side up, and sole extension at the heel. c 1870s to 1880s.

In the Spiers catalogues, wedged planes were offered right up to the final publication, but in reality, they were curtailed around World War One. By the 1880s, any wedged Spiers planes were rare (with the exceptions of the shoulder and rebate planes), but in general, Spiers favored the lever cap arrangement from the beginning of his career. Even Spiers chariot planes had lever caps when other makers almost invariably used bridges and wedges. Front and rear sole pieces are dovetailed together at the mouth in this example.

Inverted Cupid’s Bow

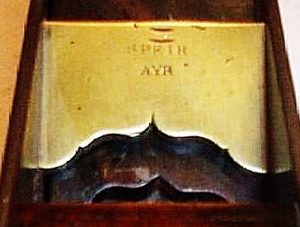

Spiers mitre plane, c. 1845 to 1863, with inverted cupid’s bow Speir type bridge. This example has the standard SPIERS AYR stamp upside down.

The inverted cupid’s bow bridge on these mitre planes were inscribed at least five ways: SPIERS AYR; SPEIR; SPEIR AYR; G. RUTHERFORD; RUTHERFORD AYR.

Who made the planes with the unique inverted cupid’s bow? In his book Through Much Tribulation: Stewart Spiers and the Planemakers of Ayr, Nigel Lampert discounted the notion of more than one Spiers making planes in Ayr:

It has been suggested elsewhere that the use of alternative spellings might indicate that more than one planemaker was responsible for early planes usually assumed to be by Stewart Spiers’. However, there is absolutely no hint or evidence that another planemaker named Speir ever existed in Ayr (or indeed elsewhere) during this period, and given that some early mitre planes marked ‘Speir’ are also marked ‘Ayr’ as well, and an early block smoothing plane is known stamped with both ‘Speir’ and ‘Spiers Ayr’, it is a reasonable assumption that the Spiers family used and/or responded to a number of spellings of their name.

Multiple spellings of an individual family’s surname was common from the beginning of surnames to the late 19th century. Consistent spelling of names only entered general practice when literacy became relatively universal, and a practical average competency became the norm.

While Stewart Spiers may have rebadged some Rutherford planes, from time to time he may have had some help from within his family as well. Stewart’s father William, a cabinetmaker (1778-1844) could have helped him make planes. Stewart’s nephew, William, born 1833, son of Stewart’s deceased brother Alexander and Mary, may also have helped Stewart make planes.

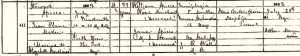

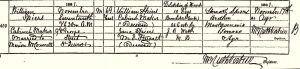

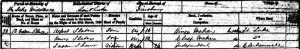

William Speirs, “Cabinetmaker Journeyman,” at [178] High St., Ayr, Scotland, with wife Marion, and son William (died as young child). 1841 Scottish U.K. census.

Other interested parties believe that Stewart’s brother William (1812-1881) was the ‘other Speir planemaker.’ A piece of information to bolster this idea was the propensity for William and his family to spell their name Speir, or Speirs, rather than Spiers, but not always. George Rutherford, the only other independent metal planemaker in Ayr, was another contender.

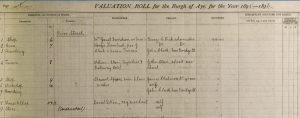

William Spiers, proprietor of the Stewart Spiers Iron Plane Workshop, 3 River St. 1875-6 Valuation Role for the Burgh of Ayr, Scotland.

With all of the interest and attention towards fine hand planes in the last several decades, Stewart Spiers has justifiably earned a great deal of recognition for his life’s work. But during Stewart’s lifetime, William Spiers played an instrumental role within the Spiers family. As the oldest son, he was an active owner/property manager of several of the Spiers family properties. Indeed, during the 1870s, William served as landlord of the Spiers workshop, and the Spiers house at 22 Garden St: “William Spiers,Cabinet Maker, @lago [personal representative] per Stewart Spiers, Iron Plane Maker, Wallacetown.” Additionally, James Davidson and Brodich Arran served as landlord representing Stewart Spiers for his property at 1 River St.

William Spiers, proprietor of the Spiers 22 Garden Street residence. 1875-6 Valuation Role for the Burgh of Ayr, Scotland.

Also, during this time, on a personal level, Spiers matriarch, Jane Stewart Spiers chose to live with her eldest son William. This also reflected the importance of William’s role within the Spiers family.

William Spiers, “cabinetmaker,” 59, wife Marion, 58, and Jane Stewart Spiers, 85, living at [64] George St., Ayr. 1871 Scottish U.K. census.

William Spiers, “Cabinetmaker,” died in Ayr, Scotland. 17 November, 1881. Reported by Stewart Spiers.

The following 3 death certificates may offer up some clues as to whether or not William helped out his brother Stewart in the shop. First, we have William’s death certificate in 1881, where Stewart was the one who reported the death. In William’s certificate, Stewart reported William’s profession as a “Cabinetmaker.”

When William’s wife Marion McConnell (m. 18 January, 1839 in Ayr) died 4 years later, William Spiers was reported as an “Iron Plane Maker,” by son in law, Donald Cameron (married to daughter Marion, 1844-1905). William Sr. was also recognized as an “Iron Plane Maker” when William and Marion’s son William Speirs Jr. died in 1906 in Ayr. William Jr. must have conveyed to Ayr Insane Asylum Steward Charles Black that his father was an “Iron Planemaker” before he passed, or the information was entered previously in the institution’s records.

Marion Speirs Death Certificate, 24 January, 1885, Prestwick, Scotland. Deceased husband William Speirs was officially documented as an “Iron Plane Maker.”

William Speirs Jr., Death Certificate, 12 June 1906, Ayr, Scotland. Father William Speirs Sr. was an “Iron Plane Maker.”

In the U.K., the death certificate was introduced in 1837; before then, church funeral and burial records, primarily from the Church of England, provided the primary death records. The death certificate was a serious government document, where accuracy was important: intentionally recording fabrications or embellishments about the deceased, could have brought consequences.

William Speir Sr. (1778-1844) may have also helped Stewart out, he likely had the potential skills, but his death in 1844 was really not long after Stewart started making planes as a sideline four years earlier. That diminished the possibility that William Sr. was making metal planes in an appreciable way.

Stewart’s nephew, William, born 9 January, 1833 in Ayr,, son of Stewart’s deceased brother Alexander Speirs (Born 22 March 1808, died 8 April 1837 in the USA) and Mary Young (1804-1853), may also have helped Stewart make planes. At 8 years old, nephew William was already living with Stewart and his grandparents, as recorded in the 1841 census. In the 1851 Scotland U.K. Census, William, 18, was a cabinetmaker living with Stewart, but I do not see any evidence on paper that he was involved in planemaking. It was reported in the 1851 Census, that William and his sister Margaret were born in the U.S.A., as British Subjects, but there was a January 1833 birth record for William in Ayr, Scotland with Alexander and Mary as parents.

William was also known to have died young, although I have not found a death certificate for him. When an individual disappeared from records, especially after 1850, it usually meant that they died or moved away: both potential outcomes reduced the likelihood that nephew William made the planes in question.

Who is to say that there was only one male family member ever to help out Stewart in his workshop making planes? It could have been any combination of these 3 Spiers family members. The real question, though, is: who had the time, skills, and inclination to make the limited output of Speir mitre planes with the inverted Cupid’s Bow, which were made to the highest standard?

Nigel Lampert argued that William Speirs (7 June, 1812- 17 November, 1881) always reported his trade as a Cabinetmaker throughout his life, and Stewart confirmed “Cabinetmaker” in his reporting for William’s death certificate: “As the evidence clearly suggests that William was never actively an iron planemaker, it thus seems likely that his family had some pretensions after his death given the obvious success of Stewart’s side of the family.”

Would William’s primary job been that of “Iron Planemaker?” Probably not. And the volume of planes in question–the scarce number of planes with the inverted cupid’s bow–would not have represented anything close to a lifetime of work. Since the scope of William’s involvement in metal planemaking would have been limited to a sideline, “Cabinetmaker” probably seemed the most appropriate title.

Looking at Stewart’s reporting for William’s death certificate as a “Cabinetmaker,” all too common foundational issues around sibling rivalry, and other unfinished business should be weighed, however. Certainly, William was a Cabinetmaker, but he also likely helped Stewart in his workshop occasionally. William’s ‘help’ may have felt to brother Stewart simultaneously, like genuine assistance, like competition, and like encroachment.

Given the spelling of ‘Speir/Speirs’ on William’s side of the family, and the fact that he was reported twice in death certificates as an “Iron Plane Maker,” decades apart, by 2 different family members, I tend to think he was the most likely male Spiers family member to have helped Stewart make planes over a substantial amount of time. And that William Speirs (1812-1881) was the most credible individual to have made the limited series of dovetailed mitres with the inverted Cupid’s Bow.

George Rutherford

George Rutherford was born in New York around 1824 or 1825, but his family was from Scotland. The Rutherford family returned to Ayr, Scotland sometime before 1845. George’s mother ran a drapery business at 124 High St., Ayr, and his planes were made at that address as well. George Rutherford made planes from approximately 1845 to 1863, at which time he had the opportunity to enter the grocery business, eventually becoming the business owner.

Along with Stewart Spiers, George Rutherford was the only other independent maker of iron planes in Ayr, Scotland. In his book about “Stewart Spiers and the Planemakers of Ayr,” author Nigel Lampert suggested that Rutherford made some of his iron planes for Stewart Spiers. Certainly, some of the mitre planes show great similarity, with the exception of the inverted cupid’s bow bridge. Perhaps the reason for the similarities had to do with Stewart Spiers’ requirement for conformity with his own mitre plane product. A very small amount of Rutherford cast panel planes and smooth planes have also surfaced.. These show little similarity to the building practice of Spiers’ dovetailed planes.

Another possibility would be that William Speir (1812-1881) made the dovetailed mitre planes with the inverted Cupid’s Bow, and Rutherford bought in a few of William Speir’s planes, then he stamped them RUTHERFORD. This would explain why George Rutherford’s cast iron panel and smooth planes bore no resemblance to either the series of mitre planes with the inverted Cupid’s Bow, or to Stewart Spiers’ line of planes, in their entirety.

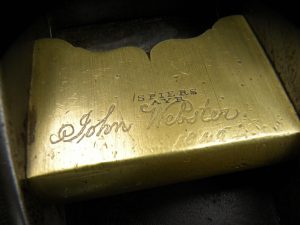

Spiers Mitre Plane, with signature of John Webster, and date of 1846. Photo from Ebay, September, 2023.

While some of the mitres are nearly identical with Stewart Spiers planes of the period, with the exception of the bridge, significant differences exist on other mitre plane examples.

SPEIR gunmetal mitre plane, as photographed in a David Stanley Auction in 2014. Planemaker Bill Carter was the high bidder, and after purchase he made a new wedge to replace the old damaged one.

After examination, Bill Carter found that this plane differed from standard Spiers mitre planes of the period in the following ways:

“…In my mind this Speir plane has absolutely nothing to do with Spiers, I think it is earlier and it is entirely different to the later made Spiers. The bridge has a beautiful cupid bow which is identical to the Rutherford makers in Nigel’s book. Again, very little is known about Rutherford as a maker.

These are the differences I have found between Speir and Spiers of Ayr:

Speir plane: The brass sides if the plane and bridge are much thicker. 2) The bridge is fixed either side with three pin brass pins, they could be tenons. 3) The cupid’s bow bridge is identical to a G. Rutherford plane and so are the overall dimensions of the plane itself. …6) The joint at the mouth appears to be like a bird’s mouth, not a tongue and groove. 7) The spelling Speir completely different, Speirs if Ayr always appears on his planes, it always has an S on the end (this is a really big difference between the two makers). 8) Brass and steel construction on his first type of dovetailed mitre plane. Spiers of Ayr did not use these materials on his first type of mitre plane. 9) The infill is solid rosewood, not made up of two pieces. 10) The front infill is a different shape.” From http://www.billcarterwoodworkingplanemaker.co.uk/new-infills/

The following Spiers mitre plane was featured in an article at oldtools.co.uk in April 2023 written by Robert Leach. This makes at least three Spiers mitre planes with the standard SPIERS AYR stamp:

Speir and Rutherford marked mitre planes from the collection of George Anderson. 2 Spiers mitre planes, c. 1840s, early 1850s in the background. Photo from 2014.

An early block smoother plane, dually marked SPEIR and SPIERS AYR, was recorded and sold by David Stanley Auctions U.K. in the 1990s. Shown below is a rare dovetailed panel plane, marked “SPEIR AYR.” The photographs are from Spiersplanes.com.

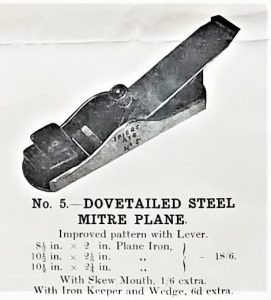

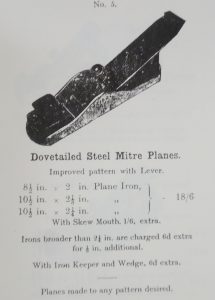

Spiers Improved Mitre Planes

Spiers Improved Mitre Plane, earliest type, with extra thin long neck on lever cap, and bulbous, decorative screw. Photo by Jim Bode, c. 2021.

Spiers Improved Mitre Plane, earliest type, showing early lever cap, and large upside down stamp. Late 1840s/early 1850s. Photo by Jim Bode, c. 2021.

Improved mitre planes were the type that Stewart Spiers was most likely to have invented from scratch. Spiers conceived his plan for the improved mitre in the 1850s–at a time when fine woodworkers were adopting bench planes made of metal rather than wood. Spiers made his changes for the improved mitre plane in an effort to integrate bench plane features into the full size mitre plane.

Spiers mitre planes, as shown in Mathieson’s 1887 catalogue. Box mitre, c. 1850-1870; Improved mitre, c. 1870-1890.

Overall configuration–20 degree bed angle iron bevel up–was derived from the traditional box mitre plane. For the rest, Spiers borrowed from the new bench planes when coming up with his design: the front bun and general side profile came from his early panel plane, the lever cap came from his early mitre plane (and others), and the rear tote was adapted and modified from his unhandled early improved smooth plane.

Early features include fairly long necked lever cap, flying saucer shaped lever cap screw with small diameter threaded stem, and screwed sides. The preceding early details apply generally to the full range of Spiers planes. Particulars more specific to Spiers’ improved mitre planes include smaller indentations on the sides of the rear infill (they became deeper gradually over time), and the absence of a rebate in front of the tote at the toe. Later Spiers improved mitre planes added a rebate in front of the tote.

Another example of an early Spiers Improved Pattern Mitre plane, with typical early features from the 1850s. While the original Ward iron is short, the plane itself is in good shape, with a fine mouth.

Some Mathieson Improved Mitre Planes

Most all metalwork–body and lever cap/screw–resemble Spiers, but rounded infills are unique to Mathiesen. A 2nd version of this plane is cast iron, with a fitted front sole. Both are very rare and sought after planes. This particular mitre has been for sale on Ebay UK for a very long time. The asking price is $18,200.00, which is why it is still up for sale. Nevertheless, it is a valuable, scarce, and historically significant plane.

Earlier photo of the same plane.

The Mathieson rounded infills were overstuffed, so that this model did not need the chamfers along the upper edges of the metal sides.

Mathieson mitre plane that sold in the November 2019 Brown Antique Tool Auction. Photo from Brown Antique Tool Auctions.

Here is another example of the dovetailed version of the Mathieson Improved mitre plane.

I have not seen the plane pictured below in person. Before coming to any conclusions about the adjustability (if at all) of the mouth, seeing it in person would be a prerequisite.

Early cast iron wedged Mathieson Improved mitre plane. Photo by Brown Antique Tool Auctions, May 2021.

A slightly later Mathieson Improved mitre plane, probably cast iron. Photo by Brown Antique Tool Auctions, May, 2021.

On the right is the early Mathieson improved mitre plane, with a cast iron body, and fitted front sole piece, circa 1860s. In this plane, the mouth is not adjustable. The Mathieson improved mitre on the left was most likely bought in from Norris, and dated circa 1899-1914.

In the foreground is a Spiers No. 5, and the other is a Mathieson No. 847/Norris No. 11 Improved Mitre plane. The Spiers is a typical version of the No. 5 for the period 1875-1895, with the exception of the doubled lever cap screw. On this Spiers No. 5 example, there is a lower profile generally (front bun and sidewalls/cheeks), with the exception of the height on the rear infill, which is 1/2″ higher than the Norris. Here you can see how Norris copied Spiers’ small lever cap, which he introduced as early as the 1860s, with small diameter threads on lever cap screw.

One way to gain a sense of the date on these early improved mitre planes is to carefully remove a side screw holding the infill. They are typically handcut and blunt on the end. Machines to produce consistent and pointed screws were developed from 1849 and into the 1850s. By the 1860s, machined screws were essentially universal.

The machine made screw tapers a bit before the gimlet point, while the handmade screw has no taper, and the slot was cut by a hack saw. In some cases, the old timers would file a point on the handmade screws, and it would look filed by hand, with file marks.

Experts Weigh In on the Useability of the Improved Mitre Plane

Controversy surrounds the subject of using improved mitre planes, with some favoring them as an actual improvement over box mitres, while others refute their usefulness on any count. Joel Moskowitz, owner of the “Tools for Working Wood” store in Brooklyn, NY, has stated that the improved mitre plane was a failed design:

“…Sexy yes–a great looking tool. But poorly designed:

- The finger grips make it easier to pick up, but the balance is still way off compared to a smoother or a short panel plane.

- Also, you end up gripping it from the top, and you can’t get the power in the stroke [that] you can with a coffin shape or a normal handle. And it isn’t very comfortable to hold that way either, as the blade is in the way (you can’t grip it from the back because of the blade over hang).

- The sides are greatly reduced, so it isn’t a great choice for shooting compared to a box mitre, or any parallel sided plane.

- It doesn’t work any better than any of the bevel down smoothers, and it’s a lot harder to make (getting that superfine mouth, tongue and grooving the joint).” –Joel Moskowitz, Woodcentral.com archives, 13 March, 2004

Contested applications would include shooting mitres as well as general smoothing, primarily on various hardwoods. Chris Schwartz, a well known woodworker, writer, publisher, and educator, wrote about the usefulness of the improved mitre plane when trying out an example of the form by Brian Buckner:

This tool is what’s called an “improved miter” pattern of plane. It’s a form that is related to the box-shaped miter shown at right and below. What’s improved about it? Well you can use it like a smoothing plane, which is something I’ve become comfortable doing. Buckner’s tool fit in my hands and was effortless to get set and take beautiful shavings.

—From “Handplane Essentials,” pub. 2017 by Chris Schwartz.

Chris Schwartz has also purchased an improved mitre plane made by Wayne Anderson, in 2004. It was stolen from him, and then he got it back. You can read about it here.

When designing his 98 smoothing plane, Karl Holtey was influenced by the improved mitre plane design. Derek Cohen quoted Holtey regarding this in one of his reviews on handplanes:

Another recent and significant deviation from the bevel down path is the Holtey #98 smoother. Karl Holtey conceived the design for this plane in 1998 (hence its name) by integrating his A11 improved pattern mitre plane[s] with a 20 deg bed and an A2 blade. Karl’s motivation to follow this construction is summed up in his own words:

“By presenting the blade in this format the need for a chipbreaker has been eliminated (I do not believe in the use of chipbreakers anyway). The blade is supported very close to the cutting edge by virtue of its being inverted. Using mitre planes of the same format I found that they worked better as smoothing planes than smoothers and I was therefore determined to design this blade configuration into a smoothing plane.

George Anderson, a well known antique tool collector and a lifelong professional woodworker has used the improved pattern mitre plane quite a lot over his many years of experience. This is what he has stated about it:

The improved mitre is to be used vertically or normally, mainly with the stock held in a vice or mitre chop. The detents at the back give better grip as you put your palm around the heel, and your fingers pinch the grips in the side.

–George Anderson, c. 2015 and 2020.

Selection and use of tools in any trade is ultimately a personal matter for the craft worker, and there is bound to be variations in patterns and frequency of usage with each and every tool. The improved mitre plane is no exception.

There are not many ‘failed designs’ that would have had as long of a run as the improved mitre plane, which was introduced by Spiers in the 1850s (Spiers Improved Mitre Planes: <1855-1914) and still made by Thomas Norris Jr. as late as 1940 (Norris Improved Mitre Planes: c. <1885-1940). So the improved mitre plane was neither an overwhelming success nor a complete failure. Most accomplished woodworkers who tried one could not justify the cost, and chose bench planes or shoulder planes (or others), as a better return on investment. A few craftsmen did try the improved mitre plane and decided to purchase one. Granted, this particular demand was specialized and limited, but the improved mitre was made for a good 80 plus years.

- Spiers with small indentations on rear infill; no shoulders at heel c. 1850s.

- Spiers with large indentations on rear infill; no shoulders; this example c. 1870-1890.

- Spiers with large indentations on rear infill; small shoulders; this example c. 1875-1895.

- Spiers with large indentations on rear infill; continuous shoulder at heel; this example c. 1895-1900.

- Norris (Mathieson 847) with cello-shaped rear infill, low flat top; this example c. 1910-1914.

- Norris, with large monolithic style infill, which was introduced post-WWI; this example c. 1935-1940.

- Norris, with ship-stern long infill; custom A11 c. 1939.

A clear, direct progression of infill styles is not literally indicated here; there are early screw-sided Spiers Improved Mitre Planes with shoulders on the infill at the heel, and there are some c. 1900 examples with no shoulders. In order to arrive at a time frame for production of any given Spiers plane, all the details must be taken into account, and an estimate made based upon this compound approach.

- Spiers c. 1850s, long lever cap, thin screw, and no rebate on leading edge of bun. Ward iron.

- Spiers 1870-1890 slightly shorter lever cap, thick lever cap screw with cusp. Howarth iron.

- Spiers 1875-1895 very short lever cap, custom screw with cusp. Ward iron (stamp truncated by work on nib–all parts stamped 5)

- Spiers 1895-1900 custom lever cap with rounded edges and intermediate size. Domed screw with no cusp. Ward iron.

Collectors seek improved mitre planes out because of their rarity and uniqueness. They are by far the most rare type of full sized infill planes. It doesn’t hurt that Norris made a limited few improved mitres and those have become something of a holy grail with aficionados. Norris planes have always held a certain mystique, and that has captured the imagination of some collectors. More on Norris improved mitre planes can be found here.

More Spiers Improved Mitre Planes, and Others

Norris no. 11 improved pattern mitre plane. Most of Norris’ line of planes borrowed heavily from Spiers, and this mitre was a prime example of that. Some Norris improved mitres were rebadged as Mathiesons. Drawing from Norris’ 1914 catalogue. Image from Norrisplanes.com.

The vast majority of antique improved mitre planes, however, are the Spiers examples, which were made from the 1850s right up to the onset of World War One. Improved mitres were always a relatively low production/specialist type plane for Spiers, but because they were made for ~60 years, they’re rare, but not the rarest. Spiers’ Thumb planes, or Spiers’ Cooper’s Plucker are examples of types more rare than Spiers’ Improved mitre planes. Offered alongside Spiers’ box mitre planes for their entire production run, Spiers improved mitres were intended to be an alternative rather than a replacement for Spiers’ traditional mitre. Several modern planemakers produce improved mitre planes, and the small market that created this demand consists of current traditional woodworkers as well as collectors. New improved mitre plane products give today’s woodworkers a chance to experience these low angle bevel up planes for themselves.

Catalogue image shows a very short lever cap and cusp on lever cap screw. I am not sure how current the image was in 1909. Bench planes in this catalogue show flat lever cap screws with no cusps. So strong selling planes were shown with the latest features while slow sellers and special order/out of production models showed older features. Planes that showed 19th century details such as a cusp on the lever cap screw included the Improved mitre, Box mitre, Thumb plane, and Chariot plane. Very few of the latter listed planes were made after 1900.

Spiers improved mitre plane with very short lever cap with a small SPIERS AYR stamp correct way up. Because the lever cap screw has a cusped design with a small diameter thread, I think that this was a 19th century plane rather than an early 20th century example. Photo by spiersplanes.com.

This Spiers improved mitre plane shows a combination of early and late features. Early features: no rebate in front of tote; cusped lever cap screw; small diameter thread lever cap screw. small upright SPIERS AYR stamp on lever cap. Late features: riveted sides; large indentations (finger holds) on rear infill; shoulders on rear infill at the heel.

The following two photos show a Spiers no. 5 improved mitre plane made in the early 20th century, as late as the onset of WWI. It shows a large SPIERS AYR stamp and a completely flat-topped lever cap screw, typical of c. 1910 or so. Truly the end of an era; there were no Spiers mitre planes manufactured after the Great War. Also discontinued at that time were the chariot and thumb planes. Photos by Aled Dafis (photobucket).

This example differs from the previous short lever cap by having a large thread on the cusped double screw. –And an original iron with straight sides rather than dog-eared.

Two ‘improved pattern’ Spiers mitre planes, both made c 1875-1895, with the small right-side up Spiers Ayr inscriptions.

Spiers cut the end of the iron off when he squared off the end of this iron; only 1/4th of the stamp remains, but the iron is numbered to the plane.

The plane on the left has a small lever cap similar to what Norris used in their mitre planes later on, and a double lever cap screw somewhat like C. Bayfield, Nottingham, but with an early style Spiers cusp. Mitre in front is slightly larger than the other one, and has thicker gauge steel stock, but the plane in back is by no means of light construction.

“With extra keeper and wedge, 6d extra.” –From the 1909 and 1911 Spiers catalogues. The wedged example of Spiers’ Improved mitre plane shown below shows signs of manufacture c. 1875-1895: infills are held in place with rivets, the recesses on the the rear infill are large, and there is a rebate at the front of the tote.

Spiers Improved mitre plane, c.1875-1895, with Cupid’s bow bridge and wedge. Photo from Jim Bode Tools, 2021.

Bridge on Spiers Improved mitre plane, similar to the earlier Speir-type inverted Cupid’s Bow. Photo from Jim Bode Tools, 2021.

Interestingly, the bridge has a similar, but not identical pattern to that found on early Speir/Spiers/Rutherford mitre planes with the inverted Cupid’s Bow, circa 1845-1863. This may have been a homage by Stewart, to his older brother William, after his death in 1881.

The following Spiers Improved Mitre plane (c. 1895-1900) is an increment smaller than most of this type, with a 2″ nibbed Ward iron. Most Spiers Improved Mitre planes and full sized Norris Improved Mitres have 2 1/4″ irons. With only a small reduction in the size of the iron, came a corresponding diminution of all the proportions on the plane. Generally, Spiers Improved mitre planes are 10 3/4″ to 10 7/8″ long, while this example with a 2″ iron is 10 5/16″ long. It differs in the details, from other Spiers Improved Mitre planes made at the end of the 19th century in the following ways:

- Long rectanglar flange extension at the toe.

- Sharp leading edge of the front infill, with corresponding 90 degree corners at the front of the sidewalls.

- Rounded edges on the lever cap, not unlike Spiers bench plane lever caps post WWI.

- Lever cap has unusual size: larger than Spiers’ smallest, but not as large as Spiers typically used on many of his mitre planes at the turn of the century.

- Rear infill has 1 continuous shoulder, rather than 2 separate shoulders at the heel.

- Front and rear sole plates are joined around 2 rod segments on each side of the mouth, emulating a rare practice by Robert Towell.

Heel of Spiers Improved Mitre Plane. With all these unique details, no matching batch numbers were needed.

Moseley Mitre plane, made by Robert Towell, with front and rear sole pieces joined around a short rod segment, instead of tongue and groove joint. Photo by George Anderson, c. 2017.

Towell Mitre Plane, 5″ long, with sole plates joined by rod. View of sole (mouth has been opened up).

Joining the sole this way was a very rare practice for Towell; mostly, he used a tongue and groove joint here. Spiers must have noticed Towell’s unusual method, and tried it himself some 60 years later.

This catalogue is dated by the dovetailed “Plane ‘O’ Ayr” as well as the concurrently available malleable iron “Plane ‘O’ Ayr” versions. At 18/6, the improved mitre plane was less expensive than the smoothers. Today, the improved mitre would be among the most expensive of these planes. The embossed lever cap, introduced circa 1914, was not yet pictured.

Stewart Spiers: Death, and Afterwards

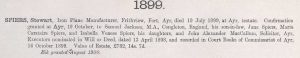

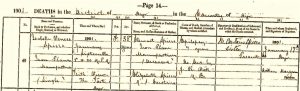

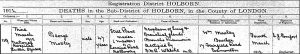

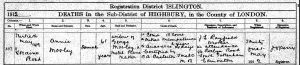

Cause of death: “Hemiplegia, 8 months; Nervous Exhaustion, 12 days.” Hemiplegia is paralysis of varying degrees, on one side of the body. The most common cause of this is hemorrhagic stroke.

“Goodwill of the business–Iron Plane Manufactory,” £100, not including stock in trade valued at £319.” From will of Stewart Spiers, 16 October, 1899.

Information for the 1900 Ayrshire City Directory would have been collected in the 2nd half of 1899.

After Stewart Spiers’ death on 19 July, 1899, his daughters ran the business. Isabella, the youngest, was in control from the 1890s until her premature death from complications around epilepsy on 16 January, 1901.

Stewart’s surviving three daughters formed a partnership with Glasgow businessman, Norman Eadie.

Help from Norman Eadie (1870-1953) would have been in the form of business advice, but it may have also been financial, as Norman Eadie came from a wealthy family. Norman’s father and uncle were successful boiler tube manufacturers in Glasgow. While the Eadie family were members of the Secessionist Church, like the Spiers family, there may have been a closer connection: Norman Eadie’s first wife, Jane “Jeanie” Speirs Nicol (1872-1913) was likely related to the Spiers family in Ayr. Jane’s maternal grandfather was David Speirs (1811-1873) of Paisley, Scotland. After Jane Speirs Nicol died of cancer in 1913, Norman Eadie resigned his partnership in the Spiers Planemaking business.

Jane Stewart Spiers, “Manageress of Spiers’ Iron Plane Works.” Firth View, Ayr. 1901 Scottish U.K. Census.

At the time, Jane Stewart Spiers was the sole remaining daughter living in Ayr. Along with Norman Eadie, and shop foreman, William McNaught, Jane Stewart Spiers managed the plane making business in the initial years following the death of Isabella in 1901.

“Heirs of the late Stewart Spiers, per John A. McCallum, solicitors…,” proprietors of 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr. 1905 Ayr Valuation Role.

Stewart Spiers, together with Isabella, likely made the decision to purchase 2-4 River Terrace before Stewart’s death.

Maria Carstairs Spiers, 20 Midton Rd., Ayr, “Iron Plane Manufacturer.” Jane Stewart, “private means.” 1911 Scottish U.K.Census.

Sometime before 1911, Maria Carstairs Spiers returned to Ayr to help manage the Spiers business.

“Stewart Spiers Planemaker” at 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr. 1915 Ayr Valuation Role. Jane, Maria, and Mary Spiers, co-owners of 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr.

Stewart Spiers Planemaker” at 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr. 1920 Ayr Valuation Role. Jane, Maria, and Mary Spiers, co-owners of 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr.

For the day to day shop operations, William McNaught, who was making Spiers planes in the shop since 1898, became superintendent early on. In the Spiers patent of 10 March, 1910, for the “Plane-O-Ayr,” William McNaught figured prominently. The budget “Plane ‘O’ Ayr” line was attributed to his innovative work towards increasing production, and meeting the market, by offering a line of planes at lower price points.

William McNaught, Joiner, moved from his birthplace Tarbolton, Ayrshire, a small village 7 miles northeast of Ayr proper, to 7 Gordon Terrace, in Ayr, in June 1895.

Robert McNaught, birth certificate, 19 August, 1898. William McNaught, “, Iron Planemaker” 7 Gordon Terrace, Ayr

In August 1898, when Stewart Spiers was still working, William McNaught was an “Iron Planemaker,” at 11 River St., Ayr.

After the deaths of Stewart Spiers in July, 1899, and Isabella Spiers in January, 1901, William McNaught was necessarily promoted to foreman of the new workshop at 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr.

William McNaught would continue to lead the daily operations at the 2-4 River Terrace Workshop until 1922, when John McFadyen bought the business. By 1933, McNaught, 64, declined to make the move to Paisley; at that late date, McNaught was understandably less motivated to make a new start.

Other than Stewart Spiers, no one made a larger contribution to the Spiers planemaking firm than William McNaught.

The 4 year old boy in the photo was William McNaught’s youngest son, Ninian Thomson McNaught (1915-2003). Photo from N. Lampert.

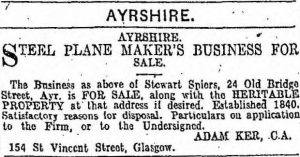

Spiers’ daughters advertised the family planemaking business for sale in “The Scotsman,” 6 December, 1921.

Business was slow after the Great War, and the daughters began their endeavor to sell the business, which was eventually purchased by John McFadyen (1866-1928) in 1922.

McFadyen continued the traditional catalogue offerings which had already been pared down to dovetailed bench planes and bullnose planes after World War One. The “Plane ‘O’ Ayr” line was updated, and the Stanley-like “Empire” line was introduced. Despite these efforts, effects of 1920s inflation, then 1930s Depression, constrained interest in all tool products that lacked economy of scale price advantages.

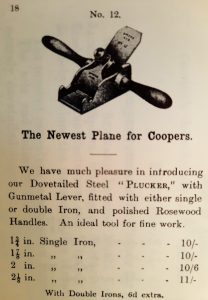

McFadyen and the Coopers’ Plucker

In the Spiers Catalogue for 1909, the Coopers’ Plucker was introduced; this was a high end tool. At a time when other specialised Spiers planes, such as the box mitre, chariot, and thumb planes, were relegated to ‘special order’ status, the Coopers’ Plucker was available in a remarkable range of 4 sizes. Since William McNaught was shop foreman in 1909, he must been instrumental in the decision to include it in the Spiers Catalogue.

Even more surprising, is that the Coopers’ Plucker was still in the Spiers Catalogue over 20 years later. John McFadyen must have made a commitment to continue offering it.

The embossed lever cap in relief was introduced on the Plane ‘O’ Ayr earlier in the century, but under the direction of John McFadyen, this unique lever cap was utilized on Spiers’ line of high end dovetailed bench planes, as well as some specialised planes, such as the Coopers’ Plucker.

Spiers Coopers’ Plucker, short sole, bevel down 2″ single Ward iron, body in cast gunmetal, and mahogany handles. Photo by George Anderson.

Unfortunately, the market for the Spiers Coopers’ Plucker simply did not exist. Coopers’ tools were usually provided by barrel making shops; coopers were hard on their tools, and this can be seen today with the heavily used condition of so many examples from that trade. Most cooperages could or would not justify the expense of an infilled plucker.

Louisville Cooperage, in the 1940s. The barrels must not leak. Image from the archives of Michael Veach

A market flop like the recondite Coopers’ Plucker was exactly the recipe for creating a holy grail of Spiers collecting. It is the rarest of all Spiers planes, and only 2 or 3 have been observed to date. The version with the long sole shown in the early 1930s Spiers Catalogue was a different design than the version with short sole and cast gunmetal body in the collection of George Anderson. The catalogue version was made of dovetailed steel, and the bevel down iron was advertised as available with or without a cap iron.

2-4 River Terrace

Auld Brig, in Ayr, Scotland, showing Spiers’ factory at 2-4 River Terrace (1899-1932). Spiers’ shop was located between the two chimneys to the right of the bridge. The sign reads “Spiers Iron Planes.” Drawing from collection of George Anderson.

Inside the ground floor of the 2-4 River Terrace Workshop c. 1900. Photo by William McNaught of his wife Barbara (N. Lampert).

The crowded workshop was a maze of belt-driven machinery. Upstairs would have been a steam engine. To the left were a batch of unfinished panel planes.

McFadyen never exercised the option of purchasing 2-4 River Terrace during his lifetime; the Spiers family sold it to the Ayr Corporation c. 1926.

“John McFadyen, Iron Planemaker,” 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr. 1925 Ayrshire Valuation Role. Jane, Maria, and Mary Spiers, co-owners of 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr.

John McFadyen, Iron Planemaker (dec.), 2-4 River Terrace, Ayr. Proprietor: Ayr Corporation. 1930 Valuation Role.

John McFadyen, “Steel Plane Maker, Master,” died 18 August, 1928 at 24 Queen’s Terrace, Ayr. Death Certificate.

At the age of 61, John McFadyen, “Iron Plane Maker,” died of heart disease at his home at 27 Queens Terrace, Ayr., on 18 August, 1928. Under the control of John McFadyen’s family, the Spiers planemaking business continued at 2-4 River Terrace, with William McNaught as shop foreman through 1932.

Spiers: The Paisley Years (1933-1937)

1-3 Lonend St., Paisley, Scotland. Now part of the Watermill Hotel, the original main structure was built on the site of a 17th century flour mill. Photo from Google Maps.

“Stewart Spiers, Iron Plane Manufacturer,” business manager, Thomas R. Lamont. 3 Lonend St., Paisley, Scotland. 1935-1936 Paisley Valuation Role.

In around 1933, The Spiers factory was moved to 3 Lonend St., Paisley. Many planes were cranked out from this facility for three years; these were something less than their best work, but circumstances and the market dictated that adjustments be made. By 1937, it was all over.

1-3 Lonend St., Paisley, U.K. Photo c. 1968 (iconic Morris Minor in foreground), from Oor Wee Toon.

Identifying a Spiers plane made in Paisley, circa 1933-1937:

- “Stewart Spiers Reg’d” trademark stamp in script on lever cap.

- Lever cap screw with chunky shape, and generic cross-hatch knurling.

- Lever cap with deeply rounded edges rather than sharp edges.

- Renumbering of dovetailed smoothers and panel planes, ranging from 22 to 32.

- “Dovetailed” stamped on front edge of sole, at the toe.

Spiers smoother c.1933-1937, closeup of toe: “DOVETAILED” and renumbering from 7a to 30. Just because it was stamped “AYR,” does not mean that it was actually made there. Photo from Spiersplanes.com

© 2024 – Martin Shepherd Piano Service Using the text, research, or images on this website without permission on an ebay auction or any other site is a violation of federal law in most countries.

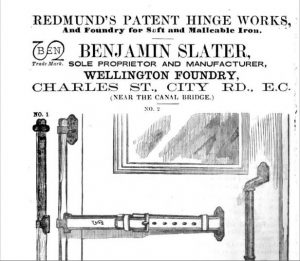

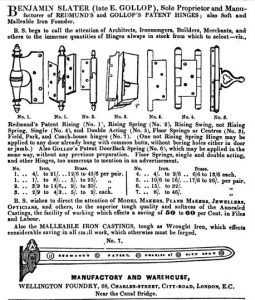

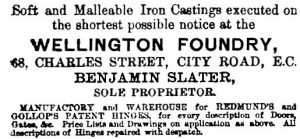

BENJAMIN AND HENRY SLATER

Henry and Benjamin Slater can be considered among the top four or five producers of English infill planes in the late 19th, early 20th century. This output was a direct result of the efficiency of casting as compared with the labor intensive process of dovetailing the plane bodies. Because the Slaters had an in-house iron foundry, they had the rare opportunity of exerting full control over their casting process and the resulting price structure. In 1881, Henry Slater had 3 men and 4 boys working for him–a crew of that size would be capable of creating large quantities of products. Making Slater planes was a team effort, and not just between the employees and apprentices. Among the family, Benjamin Sr., Benjamin Jr., Henry, Henry Ernest, and George Mosley combined their efforts to make metal planes. Another factor was Slater’s long production period, starting after Benjamin Slater took ownership of the Wellington Foundry in the early 1860s, to as late as the 1920s. The last hard evidence of Slater’s plane making that I have found, however, dated from 1911.

Standard Slater design for a mitre plane, with fitted front sole piece, rounded-off front infill, and classic Slater gunmetal lever cap and screw. Many were bought and sold without attribution.

Having earned a good reputation from fine woodworkers, the Slaters were known best in that community for their smoothers, chariots, and shoulder planes. Using the less labor intensive method of casting rather than dovetailing, the Slaters were less expensive than most of the other infill planes. In our current market, Slater smoothers, chariots, and shoulder planes that are up for sale can be found fairly readily. Relatively few Slater mitre planes remain, as not so many were made. Marked Slater mitre planes are even more uncommon. Slater mitre planes were rebadged by dealers such as Tyzack or Moseley, but most of the Slater mitres were unmarked.

A particularly fine haul of Slater planes. Photo by Mike at Vintage Tool Shop, Melbourne, Australia, September, 2019.

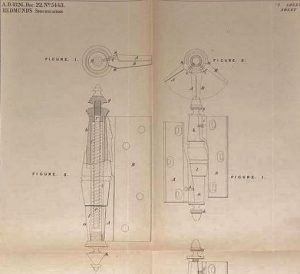

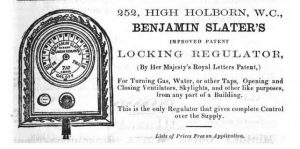

As a surprise to some current plane aficionados, Slaters’ main business was manufacturing other cast iron goods, primarily hinges. Benjamin Slater (1823-1875) also invented a gas regulator, and he built a separate factory to make them, which lasted a number of years. Along with patented rising hinges and door ironmongery, the Slater family made the cast infill planes that they are recognized for today.

Shown below is a Samuel Tyzack (Slater) cast iron mitre plane. Second photograph shows the upper and lower sole, done in a way that resembles the New York planemakers, Brandt, Thorested, Erlandsen, and Popping. This Tyzack mitre postdates Brandt and Thorested, and was stamped on the lever cap and front infill with the dual address of “TYZACK RAILWAY ARCH 345 OLD ST.; S. TYZACK 153 SHOREDITCH LONDON.”

153 Shoreditch was right around the corner from 345 Old St. This dual combination of addresses was known to be used circa 1876.

Large Tyzack sign on the right is mounted on the iron railway bridge crossing Old St. Picture was taken circa 1920, just before 345 Old St. was remodeled. Photo from tyzack.net.

Some Slater family history

A baptism for a David Slater at St. Luke’s in Finsbury was recorded on 31 May, 1778 (born 17 May, 1778). That David Slater would only have been 16 in January 1795. Given the proximity, and the fact that the Slater family on Motley St. also used St. Luke’s Church–but mainly attended St.Leonard’s–these two Slater families were almost certainly related. An 1830 burial was entered for David Slater, age 61 (born 1769) at St. Leonard’s church in Shoreditch. The burial record is compatible with both this marriage document and the later David Slater Sr. tax records on Motley St. in Shoreditch.

Detail of Shoreditch, in C. & J. Greenwood’s 1826 Map of London, showing Motley St., David Slater Sr.’s home.

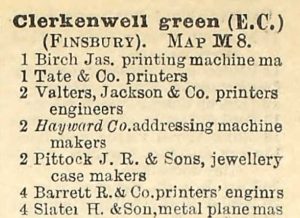

This Greenwood map excerpt also includes the locations of a number of metal planemakers, including Christopher Gabriel, 100 Old St., and Banner St. (1779-1822); Samuel Tyzack et al, 345 Old St., (1861-1975).

Jane and David had the following children: Jane, born 26 March, 1798; Sarah, born 7 April, 1800; David Jr, born 10 May, 1802; John, born 21 April, 1804. David Jr. was born on Motley St., but the family was likely there before 1798, as the 3 older children were baptized at nearby St Leonard’s Church in Shoreditch. John was baptised at St. Luke’s.

Death and burial of Jane Slater, 27 December, 1808, of Motley St., at Bunhill Field Burial Ground, City Road.

Unfortunately, Jane Slater died at the young age of 38. Christopher Gabriel was also buried at Bunhill Field, in 1809.

1831 was the last year that I could find for David Slater Sr. After 1802, and before 1831, there were a number of similar tax entries for David Slater Sr. on Motley St., enough to establish that he was living there continuously. A Mr. Wilson was his landlord.

David Slater Jr. was born 10 May, 1802 to David and Jane Slater of Motley St., Shoreditch. St. Leonard’s Church.

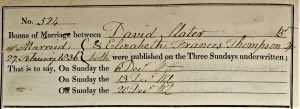

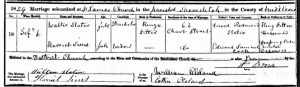

David Slater Jr. married Elizabeth Frances Thompson (1794-1878), became an engineer, and engaged in the business of hinge making. It was not that uncommon to marry years after starting a family. In the case of this marriage (1836), 13 years had passed since their firstborn, Benjamin (1823) had arrived.

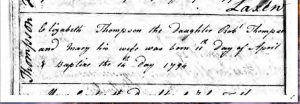

Elizabeth [Frances] Thompson Slater gave Norfolk as her place of birth in her 1851, 1861, and 1871 U.K. census entries. And 1794 was a close average for her reporting of various birth years.

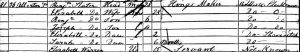

David and Frances Slater had the following children: Benjamin b.1823, John b. 1826, David, b. 1827, Walter b. 1834, Alfred b. 1836, and Henry b. 1839. While several of these sons became active in the hinge making business, Benjamin (1823-1875) and Henry (1839-1900) were the most instrumental. David Jr. died sometime before 1841.

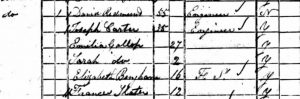

Francis Slater, widow, declared her occupation as a “Hinge Manufacturer,” and her six sons, Benjamin the oldest (also listed as a “Hinge M.F.”), and Henry, the youngest. 1841 U.K. census, City Garden Place.

Apparently, David Redmund Slater was related to inventor David Redmund (1784-1844), of the John Gollop & David Redmund Hingemaking Company, 59 Greek St., Soho, and owners of the Wellington Foundry. I had expected to find that Jane Slater’s maiden name was Redmund and not Kelly, but certainly the Slaters and Redmunds were related, by marriage and blood. In 1891, planemaker Henry Slater identified his father as “David Redmund Slater” in his marriage document.

Francis Slater Jr., 12, was living with David Redmund in 1841. This was another clue around the relatedness of the Redmund and Slater families. David Redmund’s daughter, Emilia Gollop (1814-1893) was living there as well. Emilia married John Gollop on 20 May 1838. John Gollop (1813-1851) was David Redmund’s partner in hinge making. In 1841, Emilia seemed to be taking a break from the marriage.

Emilia Gollop declared herself as a “hinge manufacturer,” at the Wellington Foundry; she lived with Fanny Slater, 32. 1861 U.K. census.

Twenty years later, Frances (Fanny) Slater was still living with Emilia Gollop, and working for her as a house servant. Benjamin Slater’s 1864 advertisements in “Skyring’s Builders’ Prices” referred to the former Wellington Foundry proprietor as “late E.[Emelia] Gollop.”

In the 18th and 19th centuries, referring to an individual as “late,” did not imply dead, necessarily. In many cases it simply meant “formerly’ or ‘previously.’

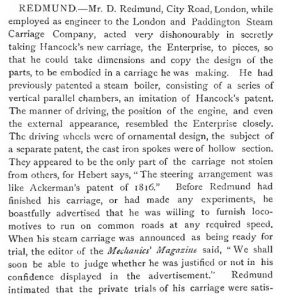

A scathing account. What was the other side to this story?

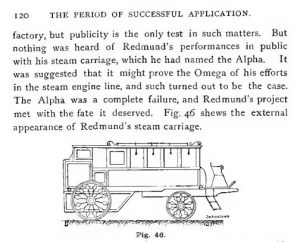

David Redmund was very active as an inventor, with his omnibus, his steam engine boiler, and his hinges. Benjamin Slater must have been working on a Redmund Steam Engine, which he documented in his marriage record with Elizabeth Scotchford in 1843.

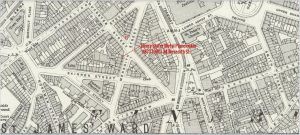

This map shows some early locations of the Slater family. Henry Slater’s later location on Wynyatt St. is shown, as well as 13 Nelson Place, and 14 Rawstorne St.. Wellington Foundry was not built when map was surveyed.

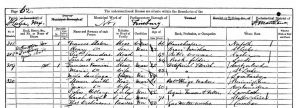

13 Nelson Place, Shoreditch, in 1851 U.K. census (part 2), including Henry Slater, listed as a “Clasp Maker.”

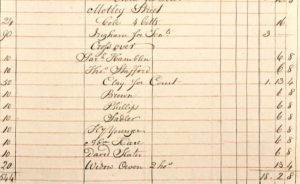

Francis Slater, declared her job as a “Laundress,” living at 13 Nelson Place., Shoreditch, during the 1851 U.K. census.

Benjamin Slater, listed himself as a “Hinge Maker,” living at 36 Allerton St., Shoreditch, during the 1851 U.K. census.

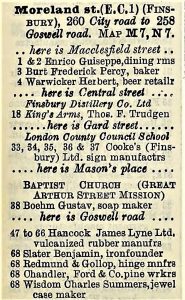

Benjamin Slater, declared his job as a “Hinge and Lathe Maker,” and Benjamin Jr., listed himself as an “Engineer’s Apprentice,” at 14 Rawstorne St., Clerkenwell, in the 1861 U.K. census.

Frances and Henry Slater, Foundry Yard, Wellington Foundry, in 1861 U.K. census. Henry was a “Brass Finisher.”

Benjamin Slater’s Wellington Foundry, from the “English Mechanic and Mirror of Science and Arts,” 6 August, 1869

Frances Slater, “Owning Account” (retired) back at 14 City Gardens, Islington (Clerkenwell), during the 1871 U.K. census.

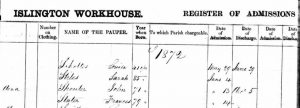

Frances Slater was admitted to the Islington Workhouse at Barnsbury and Liverpool Streets., 14 June 1872.

Hinges, Gas Meters and Planes, etc., cast at the Wellington Foundry

“Benjamin Slater wishes to direct the attention of Model Makers, Plane Makers, Jewelers, Opticians, and other, to the superior tough quality and softness of the Annealed Castings, the facility of working which effects a saving of 50 to 60 per Cent in Files and Labour. Also the MALLEABLE IRON CASTINGS tough as Wrought Iron, which effects considerable saving in all small work, which otherwise must be forged.” 1864 Skyring’s Builders’ Prices.

David Redmund’s Patent Rising Hinge was very popular and successful. The Slater family dynasty was involved in producing it for 100 years:

- David Redmund Slater c. 1825-1840.

- Francis Slater (David’s widow) 1840-c.1845.

- Benjamin Slater and E. Gollop 1845-1875.

- Benjamin Slater Jr. and Henry Slater et al 1875-1920.

- Henry Ernest Slater 1920-1929>.

It did not make them rich.

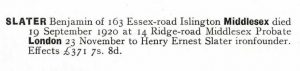

The Redmunds, Gollops, and Slaters, had most of the requirements for success: good ideas, an in-house facility, and an ample labor pool. But near the end of their full century of trading, no appreciable amount of capitol was attained. Benjamin Slater Jr. died 19 September, 1920 with less than £400 in savings.

Benjamin died relatively young, raised a large family, and assumed ownership of the Wellington Foundry in the early 1860s. This would be around $300,000 in 2020. For owning a medium sized business that dealt in high volume, this was a decent amount of savings, but still relatively modest. Benjamin and Elizabeth gave two of their sons Redmund for their middle name: Henry William Redmund Slater (1857-1935), and Ernest Redmund Slater (1865- 1896 ). Also, Benjamin and Elizabeth named one of their daughters, Elizabeth Frances (1849-1879) which was a tribute to her mother, but also to her grandmother, Elizabeth Frances Thompson, born in Norfolk, circa 1794.

Benjamin Slater Jr.

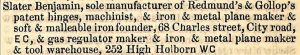

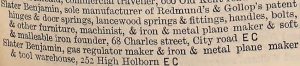

Benjamin Slater Jr. took over the business of his father, and continued to produce an abundance of products. The 1875, 1880, and 1891 Kelly’s London Trades Directory entries show Benjamin Jr.’s involvement in planemaking. An omission is apparent in these entries, it should read: ” …iron & [gun]metal plane maker & tool warehouse.” Production plane making likely began after Benjamin Slater Sr. assumed ownership of the Wellington Foundry from Emelia Gollop after 1861, but no later than 1864. A small number of planes have been found, stamped “Benj. Slater London.”

Charles Street was change to Moreland Street circa 1885.

Henry Slater, Planemaker

I think this was a misclassification. Henry Slater was an ironfounder, making hinges and planes. Henry did not make iron plates of the rectangular or circular kind, and he did not plate metals either. In another part of the 1870 directory, Slater was listed under “Iron and Tin Plate Workers.” Regardless of the possible oversight, Henry Slater had at least two years to follow up and clarify his moniker. But he did not.

“iron plate worker ; iron plater; cuts iron plates on table of power shears; bends, in bending machine or with hammer on block shape; rivets and fits up iron plates generally in connection with constructional iron work; cf. plater. From A Dictionary of Occupational Terms Based on the Classification of Occupations used in the Census of Population,”1921. Compiled by the Ministry of Labour and published by HMSO, 1927.”

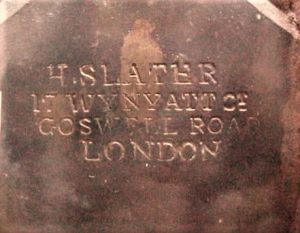

In March 2022, an early Slater mitre plane came to auction on ebay, bearing Henry Slater’s early address on Wynyatt St. This 8″ cast iron mitre plane was rusty and in rough shape, but it demonstrated that some of Henry’s earliest planes were mitre planes: the front infill, general casting layout with separate front sole piece, and lever cap show that this design was consistent throughout his career. Only the lever cap screw was different.

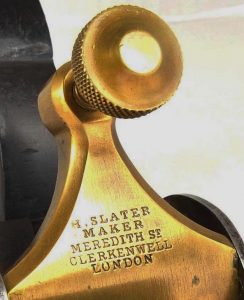

“H. Slater Maker.” Henry would have received the unfinished castings from Benjamin Jr. and then finished them off himself.

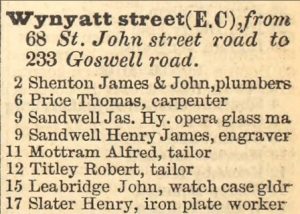

Henry Slater, declared his job as a “Planemaker,” living at 17 Wynyatt St. (1868-1872) Goswell Rd., Clerkenwell, in the 1871 U.K. census.

Almost all of the Slater Planes were stamped “H. [Henry] Slater.” Since the planes were signed by Henry, it is a sound assumption that Henry was primarily (but not exclusively) responsible for finishing off the castings from Wellington foundry, fitting the infills, and the irons.

Listings as “Planemaker,” in the 1871, 1881, and 1891, U.K. census entries, underscore Henry’s specialization in this area.

17 Wynyatt St. as it appears today. It was built in 1804. Photo from Zoopla.co.uk

The block of Meredith Street containing no. 34 has since been razed for urban renewal.

Henry Slater, declared his occupation as a “Metal Plane & Spring Hinge Maker; Master of 3 Men, 4 Boys,” 34 Meredith St., 1881 U.K. census.

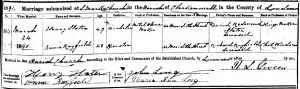

Henry Slater, listed himself as a “planemaker,” and married his longtime partner Annie Rayfield at St. Mark’s Church, Myddleton Square, Clerkenwell, on 24 March, 1891.

For some reason, in the 1881 and 1891 U.K. census entries, Annie Rayfield Slater was reported as “Amy,” but her birth year, 1851, was consistent in all records. Annie was recorded as “Ann Rayfield” in her 1861 and 1871 U.K. census entries. Henry’s father, deceased, was recorded as “David Redmund Slater, Hinge Maker.”

Henry’s mother Frances stated Henry’s birth to be 1839 in the 1841 and 1861 census entries. Henry shaved two years off his age, and gave 1841 in all documents from 1871 onward.

Neither neighbor Elisa Patrick nor registrar John Weigler knew or cared about what Henry Slater did for a living, as he died as a singular “Master Screw Maker.”

After the death of Henry Slater.

Annie Slater continued to live at 34 Meredith St. (maintaining the listing under Henry’s name) until 1908, and presumably continued the business along with Benjamin Slater Jr.

George Mosley

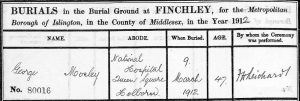

George Mosley (1864-1912) worked with Henry Slater for most of his life. After the death of Henry Slater, and along with Benjamin Slater Jr. (1845-1920) and Henry Ernest Slater (1878-1942), he continued the family planemaking business.

There was no known connection between George Mosley and the Moseley dynasty of tool dealers, though Henry Slater sold a number of his infill planes to the Moseley enterprise for rebadging as Moseley planes.

At the time of the 1871 U.K. census, George, age 6 was being raised at 16 Wynyatt Street, next door to Henry Slater at 17 Wynyatt St. Henry Slater was single in 1871.

George Mosley, declared his job as an “Iron Planemaker,” age 16, living at 16 Wynyatt St., Clerkenwell. 1881 U.K. census.

Ten years later, George was an iron plane maker, working for Henry Slater, who had moved to 34 Meredith Street to live with Annie Rayfield.

In 1901 George Mosley was working for his “own account,” which could mean that he was producing as a piece worker for Slater. Or it could also indicate that George was participating in profit sharing from the Slater business, in more of a leadership role after Henry Slater’s death in 1900.

In 1908, George Mosley married widow Annie Slater, and in the 1911 U.K. census, was again working as an “Iron Plane Maker,” for his “own account.”

Sadly, after less than 4 years of marriage, George Mosley died. Just three months later (also in 1912) Annie died as well.

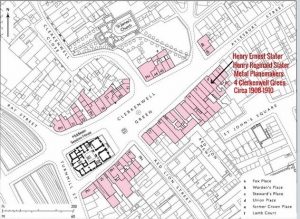

H. Slater & Son Metal Plane Makers, 4 Clerkenwell Green

Henry and Annie Slater did not have children, so the 1909 and 1910 listings below could be Henry W. R. Slater, (1857-1935), son of Benjamin Slater Sr., or Henry E. Slater (1878-1942), son of Benjamin Slater Jr. Henry William Redmund Slater was a silversmith, engraver, and comb manufacturer. Henry Ernest Slater was an Iron Founder, and the more likely of the two to be a producer of metal planes.

Henry Slater & Son, listed as “Metal Plane Makers,” 4 Clerkenwell Green, from 1910 Kelly’s London Post Office Directory.

Clerkenwell Green circa 1870s. Map from British History Online.

The residential part of 4 Clerkenwell Green housed two families in 1911, the Beachams and the Walkers.

Has anyone seen a plane stamped with “4 Clerkenwell Green?”

Henry Ernest Slater, listed himself as a ” Moulder (Iron Foundry)” 163 Essex Rd., 1911 census. Likely metal planemaker.

Henry Ernest Slater and his family lived in the same house as his father Benjamin Slater Jr., at 163 Essex Road, Islington in 1911. Henry Slater had one son, Henry Reginald, born 9 May, 1901, so the 1909/10 Post Office listings “H. Slater & Son,” was likely a father’s proud nod to his young son.

Benjamin Slater, decared himself as an “Iron Founder,” 163 Essex Rd., Islington, in the 1911 U.K. census.

Benjamin Slater Jr. died 19 September, 1920. From Wills Calendar. Henry Ernest was his son. b. 1878.

Posthumous listings for Slater’s Foundry:

1929 was the last London Street Directory listing that I have encountered to date, facility apparently active.

Henry Ernest Slater, “Iron Moulder; Furnace Man; Heavy Worker,” As late as 1939, Henry E. Slater had the ability to produce plane castings. It was doubtful that they were made at this late date, however.

Life around a foundry was and is hazardous to your health. Silicosis and various cancers were common.

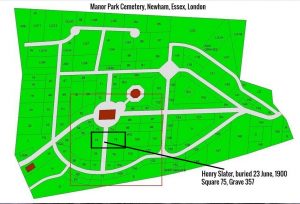

Most men in the Slater family business sadly died young: David Redmund Slater, 37; David Redmund, 60; John Gollop, 38; Benjamin Slater Sr., 52; Henry Slater, 61; George Mosley, 47; Henry Ernest Slater, 62.