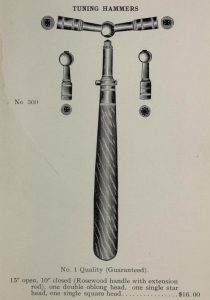

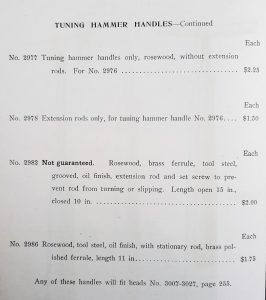

Erlandsen made hand tools that became an industry standard in four areas: bow drills, infill planes, regulating tools, and tuning hammers. I’ll start with the tuning hammers.

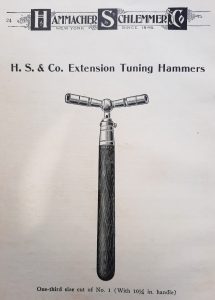

Charles Mueller 1899 patented extension tuning hammer, made by Julius Erlandsen. Picture was taken after using it to tune for a performance.

USING ERLANDSEN HAMMERS

I have used many of the Erlandsen hammers professionally as well as the Mueller hammers (Erlandsen made), and have found that they work especially well on pianos made from 1880 to 1940 that are still in original condition. This is because the Erlandsen socket is machined very well to fit the tuning pins of pianos that were new at the time: <.276” to .282”. Erlandsen hammers also work well on many fine European pianos, such as Bechstein or Bosendorfer, and some domestic postwar pianos like Steinway up to the early 1960s. They also work well on some Japanese pianos, like Yamaha and Kawai, before 1990 or so.

Erlandsen never adopted the interchangeable tuning tip featured by their main competitor, Hale, but they did offer many different heads of varying lengths, and there is some variation in the how their star socket was machined over the years. Perhaps some of this variation was a result of special orders made to the Erlandsen machine shop. Because of this, a limited number of Erlandsen heads can accommodate 3.0 tuning pins. The two set screws on the collar, one for rotational stability and the other for longitudinal stability made the fixture of the adjustable shaft rock solid, and given that the tuner typically carried several screwdrivers, the need for this separate tool for adjustment was not a detriment.

The tuning pins of these pianos have less torque, or tightness in the pinblock than new pianos, either by manufacturer’s intent, for the older ones (1860-1890), and/or through aging and seasoning. In Northern California, however, where I ply my trade, many of these vintage pianos still have surprisingly tight tuning pins as compared to those in the East Coast or Midwest which are subject to cycles of forced air heating in the winter and high humidity in the summer. The slightly lower tuning pin torque in these vintage instruments lessens the amount of flexing of the adjustable shaft on the Erlandsen hammer.

The Erlandsen shaft is somewhat narrower at ~13/32″, as compared to 7/16″ and larger for modern shafts, although the quality of the steel in the Erlandsen shafts is better in my opinion, despite all of the advances in metallurgy over the intervening years. Dealing with the flexing of tuning pins was and is an inherent part of the tuner’s job, and until the recent introduction of carbon fiber tuning hammers, dealing with some flex in the tuning hammer was also part of this task.

Erlandsen tuning hammers are not particularly useful on pins larger than 2.0 because of the relatively small size of their tuning pin socket. During the period in which the Erlandsens were active, 1863 to 1940, the piano restoration business, which would typically restring with larger tuning pins, was relatively small because the majority of pianos in the U.S. were not yet old enough to require that procedure.

SOME ERLANDSEN HISTORY

Napoleon Erlandsen, 18, in the 1850 Denmark Census. Also Eric Rasmussen, 63, and Anna Dorothea Olsdatter, 70. No 210

Fåborg købstad, Sallinge, Svendborg, Danmark (Denmark)

Napoleon Erlandsen was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in March, 1831 to parents Neils and Mary Erlandsen. Previous to immigrating to New York City, Napoleon was raised as a foster son in the house of Dorothea Olsdatter Arnesen, and Blacksmith Eric Rasmussen in Faaborg, Denmark, the mother and stepfather of machinist Lauritz Brandt. Napoleon learned blacksmithing from Eric Rasmussen as his assistant in the 1840s and 1850s.

Departure manifest of the steamship Teutonia, leaving Hamburg, 29 February, 1860. Occupation: Schlosser (locksmith/metalworker/mechanic).

Napoleon listed his departure point as Faaborg, Denmark.

Napoleon Erlandsen, 28, a “Smith,” arrived in New York City Harbor on 19 March, 1860. He was a passenger on the “Teutonia.”

Napoleon Erlandsen moved to New York in 1860, and began making tools for the piano trade around 1863. From 1860 Napoleon lived and worked from 417-419 Fifth St., which was owned by his step-brother Lauritz Brandt. Napoleon remained at Brandt’s Fifth St. property until 1877, and during the period between 1860 and 1867 was trained by Lauritz Brandt in the manufacturing of specialized piano tools. Napoleon married Louisa Aubinger (1841-1928), a first generation German-American, in 1864, and they had two sons: Oscar (1865-1943) who became a noted civil engineer, and Julius (December 5, 1866–October 20, 1956), who accompanied Napoleon in business.

Napoleon Erlandsen, 417 and 419 Fifth St. This was formerly 220 1/2 and 222 Fifth St., properties of Lauritz Brandt. Trow’s 1864 N.Y.C. Directory.

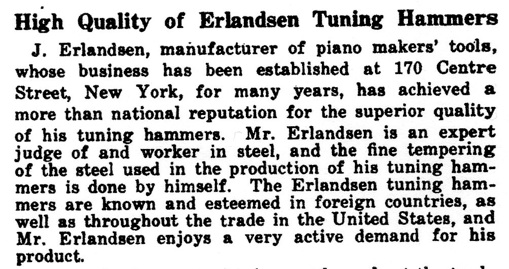

Napoleon was a skilled machinist, designer and woodworker, and he developed a tool making business that supplied Hammacher Schlemmer, Alfred Dolge, American Felt Co., C. F. Goepel, and Schley, as well as other piano tool and supply retailers outside the U.S. He developed a full line of tools for tuners, action regulators, case makers, bellymen, and other allied tradesmen.

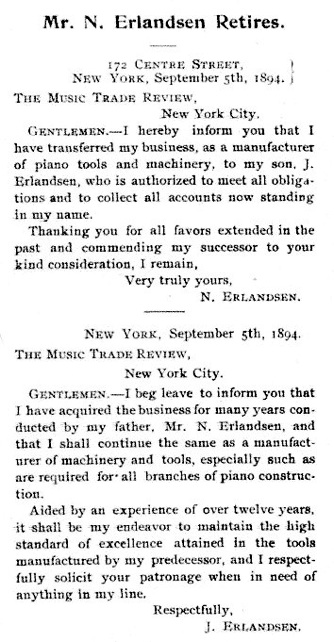

Napoleon Erlandsen handed down the business to his son, Julius. 1894 letter in the “Music Trade Review.”

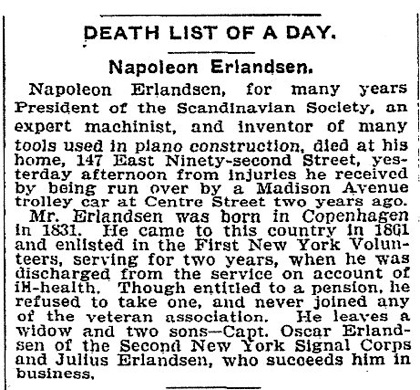

His son, Julius, joined him in the early 1880s, and they worked together until about 1894, when Napoleon retired. Napoleon was severely injured in a streetcar accident and died as a result of his injuries on July 19th, 1900. Julius continued the business until at least 1940, according to the US federal census.

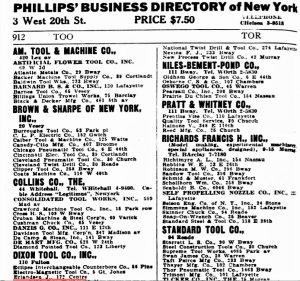

Julius Erlandsen: listing for custom model making. From “Johnston’s Electrical & Street Railway Directory” 1897.

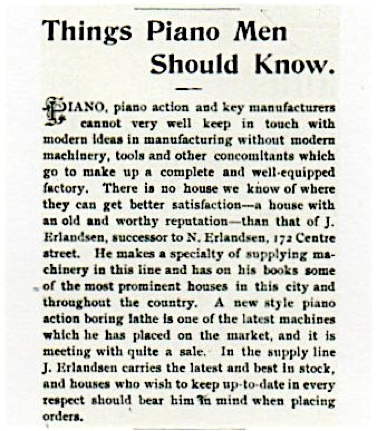

1894 article in the “Music Trade Review.”

This article revealed that Julius Erlandsen was now in control of the company, innovating, and receiving credit for it. It’s just one example of the wide range of products that the Erlandsen machine shop supplied for the piano industry.

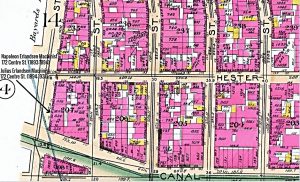

172 Centre St., N.Y.C., was the workshop of Julius Erlandsen from 1893 to 1932. From G.W. Bromley 1891 Ward Map of Manhattan.

Julius Erlandsen worked out of his 172 Centre St. shop for 39 years. When Julius left 172 Centre St. in 1932, he was not done; he would continue to work as long as 22 more years.

Erlandsen’s workshop at 172 Centre St. and the building that contained it no longer exists. The current location is used as a car parking lot.

Julius Erlandsen shared space at 172 Centre St. with his brother Oscar Erlandsen, a well known civil engineer in the New York area. From “Civil Engineers’ Yearbook for 1896.”

172 Centre St. was the former site of the notable pipe organ maker, Henry Erben (1800-1884). Advertisement from Wilson’s 1858 New York City Directory.

Julius Erlandsen was a graduate of Cooper Union, free night school. Julius became an authority in metallurgy.

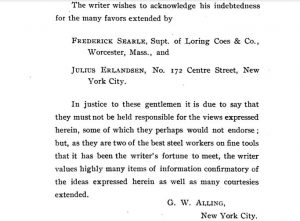

Acknowledgements from “Points for Buyers and Users of Tool Steel,” by George W. Alling. 1903. Julius Erlandsen became a recognized expert in tool steel. I can say from experience that the steel and other metals used generally in Erlandsen products is superior to many others, then and now. Incidentally, Loring Coes held the patent for the monkey wrench.

“…Mr. Erlandsen is an expert judge of and worker in steel, and the fine tempering of the steel used in the production of his tuning hammers is done by himself.” Music Trades Review, 1919.

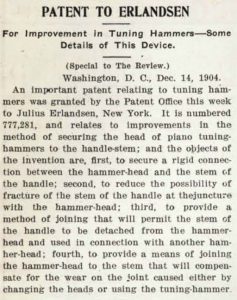

Julius Erlandsen also held at least 7 patents, which can be seen here. These patents included two for an extension tuning hammer, and others were for machinery, including a rotary cutter, and a wire mattress stretcher.

This U.S. census was to have been completed on 1 June, 1900, so this was a snapshot of the Erlandsen family just weeks before Napoleon died. Their apartment was located at 147 East 92nd St., and Julius’ shop was 172 Centre St.

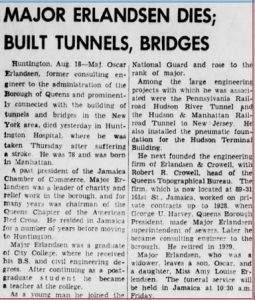

Obituary of Napoleon Erlandsen, d. 19 July, 1900. Oscar Erlandsen, who sometimes served as a witness for Julius’ patents, went on to become a well known civil engineer.

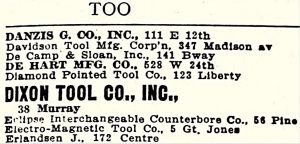

Erlandsen machine shop addresses: 417 5th St (1864-1868–shared with mentor Lauritz Brandt); 615 East 5th St. (1868-1877–also shared with Lauritz Brandt); 87 Elizabeth St (1877-1880); 107 Rivington St. (1880-1893); 172 Center St. (1893-1932); 331 W. Broadway (>1933-1940>); 37-58 84th St. Jackson Heights, Long Island City, residence and light work (1929-1953<).

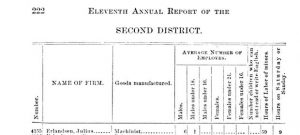

Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of the State of New York …, Issue 11. 1897. Julius Erlandsen had 6 employees counting himself.

The 19th century was not the zenith of the piano industry in the United States. Piano production reached a peak in 1909, with 364,565 new pianos sold that year, according to the National Piano Manufacturers Association. Business continued to be good until 1929. This is why Julius Erlandsen was able to continue as a machinist making piano tools until at least 1940, and possibly as late as 1954, when the Piano Supply Department was divested from Hammacher Schlemmer & Co., N.Y.

HISTORICAL TUNING HAMMERS BY NAPOLEON & JULIUS ERLANDSEN

This is an earlier version of the Erlandsen hammer, with only one adjustment set screw (later models had two), with a German silver collar and ferrule, detailing on the metal parts, and a different turning design than later versions, for the double square head (two square sockets). Star tips may have been uncommon when this hammer was made.

N. Erlandsen tuning hammer, early version. Closeup of hardware.

Erlandsen hammer inscribed with an “H” only, presumably when the company was known as A. Hammacher and Co. between the years of 1867 and 1883, after which “Schlemmer” was added to the company name:

At the back is the standard model which was offered in 1885, continued in production, and shown in catalogs as late as the 1930s. In the front is a small gooseneck tuning lever, very well made and probably produced early in Napoleon Erlandsen’s working life, c.1860s. Inside the rosewood handle, it has a steel shaft sheathed in a brass tube, with a detailed German silver ferrule and steel collar. This is much like the construction of Erlandsen’s extension hammers. It is a similar size to the antique French hammer (early 1800s) which is shown in the middle.

H.S./Erlandsen gooseneck style tuning hammer. Sold for a surprisingly high price in a May 2024 Martin Donnelly Auction. Photo from MJD Auctions.

Erlandsen’s gooseneck hammer would have found a ready market with some piano technicians who were trained in Europe, budget conscious tuners, and factory stringing chippers. Unlike most cheaply made gooseneck hammers in the North American market today, this one is carefully machined, with a solid Brazilian rosewood handle, and a German silver ferrule. The shaft is plated in nickel.

Erlandsen hammer, single set screw, steel collar. This handle has been slightly flattened on each side by the user, to provide a better grip for flipping the tool over, in order to use the opposing socket:

Before 1892: 1 large set screw with concave groove in the shaft.

Before 1892: 1 large set screw with concave groove in the shaft. Erlandsen’s was one of the most secure single screw set type tuning hammers made. There is no rotation of the shaft within the hammer during use–even when extended. Erlandsen fitted his steel shafts snugly within the internal brass tube, almost like a piston. He also mated the end of the set screw to the bottom of the routed slot in the shaft. In order to organize this hand finishing, both Napoleon and Julius used fitting numbers, in this case, 18.

Post 1892: N. Erlandsen, with two set screws, and flat groove in shaft.

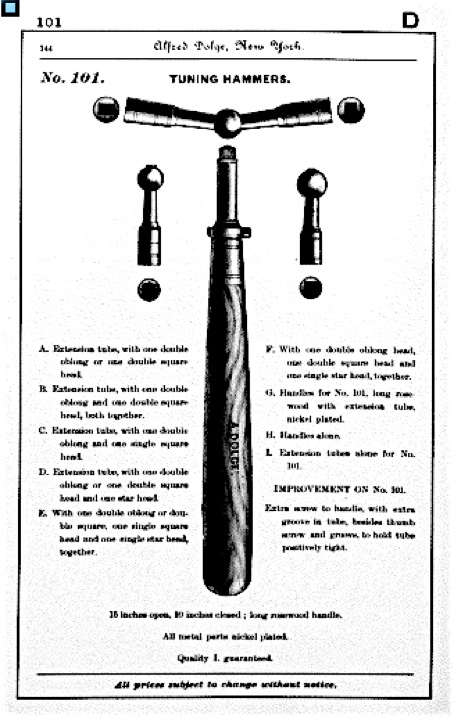

A. Dolge extension hammer, post-1892; after close examination, it was almost certainly made by Erlandsen.

Alfred Dolge hammer, either made for Dolge by Erlandsen, or Dolge’s close copy of the Erlandsen design. The two set screws are on opposite sides of the collar, and there are two grooves in the shaft for these set screws. The early 1890s Erlandsen Hammer, in comparison, had two set screws, 90 degrees apart, and one groove in the extendible shaft. The second set screw had just been added in 1892, according to the catalogue entry. This was Dolge’s top-of-the-line, “quality 1” hammer:

Alfred Dolge extension hammer, attributed to Erlandsen, as shown in the Dolge 1869-1892 pianomakers supply catalogue.

Later American Felt extension tuning hammer c. 1899-1915, almost certainly made for them by Julius Erlandsen. Its an older design, and somewhat anachronistic, with brass ferrule and single set screw. It is a solid first quality hammer, however.

Schley Catalog entry c. 1905, however, the drawing is directly borrowed from an 1894 ad in the “Music Trade Review.”

Schley, cont.

Three Tuning hammers: l. Erlandsen Extension Hammer; r. Erlandsen Stationary Hammer; middle. unmarked extension hammer. American Felt Co. Catalogue, 1911.

Variations of the extension hammer shown in the middle were big sellers from the 1880s, until as late as the 1930s. On the face of it, these looked to be a good value, but the extension rods were not sufficiently secure for professional tuning, in most examples. The reason why these discount extension tuning hammers were not as solid as they needed to be, was a result of the loose fitting of the shaft within the receptacle of the hardware and handle, and the lack of fitting the set screw to the channel or groove in the rod.

Three classic Julius Erlandsen tuning hammers, left to right:

- The first one is virtually identical to the one illustrated above, featuring two screws, one for longitudinal stability and the other for rotational stability. It is a little heavier than the earliest Erlandsen levers, with a steel collar, a tube inside the handle, and a German silver ferrule. Julius used flat sheets of German silver, which he rolled and seamed together very tightly, in comparison with Napoleon, who used tapered cylinders.

This is a very secure, usable tuning hammer, and is first quality in every respect. It was considered the standard up to the turn of the 20th century, and was still prominently featured in the catalogs through World War I, and into the 1920s. - Middle hammer is dated 1902, with an earlier head from the N. Erlandsen era, and has very minor cosmetic differences from the previous one. Erlandsen was always tweaking their hardware, sometimes for functionality, and other times for cosmetics only. All three hammers have different steel collars.

- A later version is shown on the right, and it has a thread on the shaft that is compatible with pre-1925 Hale heads.

Hale made the short pre-1925 head with attached #3 tuning tip, shown at the bottom right. Erlandsen was likely feeling the competition from Hale when this hammer was made, circa 1920 to 1925. Incidentally, Erlandsen wasn’t the only piano tool maker not to adopt the separate tuning tip. Traditional Renner tuning hammers from Stuttgart, Germany (as opposed to the Renner USA products) did not offer separate tips either.

Hale made the short pre-1925 head with attached #3 tuning tip, shown at the bottom right. Erlandsen was likely feeling the competition from Hale when this hammer was made, circa 1920 to 1925. Incidentally, Erlandsen wasn’t the only piano tool maker not to adopt the separate tuning tip. Traditional Renner tuning hammers from Stuttgart, Germany (as opposed to the Renner USA products) did not offer separate tips either.

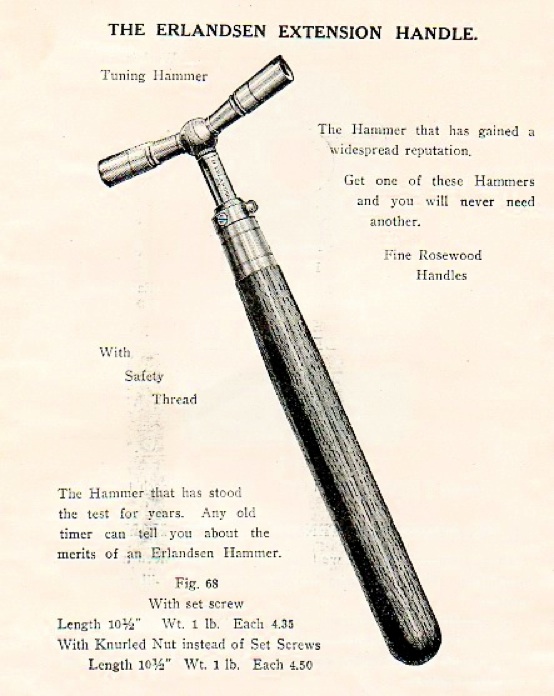

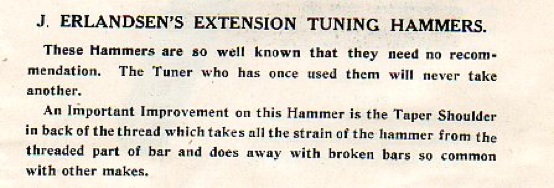

“Music Trade Review,” 1919.

Some Erlandsen tool products were carried by Otto Higel, in Toronto, Canada and J.& J. Goddard in London, England.

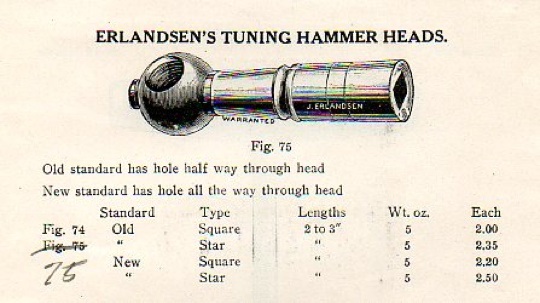

Erlandsen, Old and New style tuning hammer heads, circa 1905.

This appears to be a classic Erlandsen hammer, made by Julius in the latter period of his career.

Erlandsen tuning hammer with tapered shoulder. In the U.K., a “Steinway pattern” hammer similar to this was offered by Fletcher and Newman, LTD. in their 1976 catalogue as #488. Heckscher & Co., Ltd., a piano supply house in London, made a similar type hammer until c. 2015. While I was working in New York, I noticed a number of Steinway employee tuners that were using a short and simple tuning hammer like this:

Erlandsen tuning hammer with tapered shoulder.

A fixed shaft is secured in the handle with a machine screw running through it and the handle. Julius Erlandsen’s “Tapered shoulder” is fitted with similarly matched tapered threading on the shaft:

Anton Hubalek appeared in the 1910 census, living in Brooklyn, and working in the piano business. “Hubalek” is also included in the Pierce Piano Atlas, in Brooklyn, with a date of 1876:

An example of the Erlandsen new standard tuning hammer head with hole through head, US patent, 13 Dec., 1904. This is the “tapered shoulder” design referred to in the 1905 catalog entry above.

Julius Erlandsen’s hammer has three patent inscriptions:

- On the hammer head, Dec 13th, 1904

- On the extendible shaft, Dec. 13, 1904

- On the loose sleeve, Sept. 27, 1904

The Dec, 13 patent, again, was for the tapered shaft end that screws into a head bored completely through. This was done in an effort to eliminate breakage at the critical head/shaft connection. The Sept. 27, 1904 patent was for a loose sleeve (the knurled nut which usually is threaded, but not in this case) which, when turned a partial turn, engages an internal dog into the groove running most of the length of the extendible shaft. Julius’ design was made in an effort to eliminate the stripping and breaking of set screws, which Erlandsen had previously relied upon in most of their previous tuning hammers.

Description of Julius Erlandsen’s December 1904 Patent for tuning hammers. “Music Trade Review,” Dec., 1904.

Julius Erlandsen’s 1904 double patent extension hammer. One very easy quarter twist of the thumbscrew clockwise locks the shaft down hard.

Three tuning hammers with patent taper shoulder/head bored through, by Julius Erlandsen, l. to r.: 1904 Double Patent Extension Hammer; Original 1863 Extension Hammer with updates; Steinway style Stationary Tuning Hammer.

The tuning hammer in the middle is stamped with both Erlandsen and Hammacher Schlemmer; this is very uncommon, as H.S. did not like selling tools with anything other than their own branding.

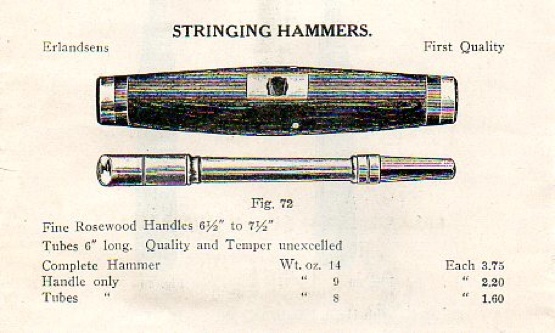

By 1905, when the following was published, T hammers were called stringing hammers (in North America), with less reference to tuning. A stringing hook was absent.

Erlandsen “T” Hammer in 1905 catalogue.

Erlandsen tuning pin extractor.

Erlandsen tuning pin extractors.

JULIUS ERLANDSEN: THE LATE YEARS

A Mueller ‘improved ‘ hammer, version 2, an example of Julius Erlandsen’s later production work during the 1930s. Photo was taken after I used it to tune this old Steinway “O” grand in a teacher’s studio.

The last year of entry for Erlandsen’s 172 Centre St address was 1932. Julius likely was forced to downsize, and move some essential equipment to a smaller space due to the loss of sales during the worst of the Great Depression. Most of Erlandsen’s 1930s tool production would have been for Hammacher Schlemmer. By this time, based on extant Erlandsen tools from the period, I believe that he was primarily producing tuning, voicing, regulating, and stringing tools. Mueller ‘improved, hammer, version 2, is one example of Julius’ late production.

Plane and bow drill production had been greatly diminished if not curtailed during the 1930s. Erlandsen’s bow drill and tuning hammers were included in Goddard’s no. 80 trade list, circa 1938-9. It was the last offering of pianomakers’ bow drills that I have found.

3758 84th St., Jackson Heights, Long Island City, Queens. Some of the apartments are 800 square feet. Photo from Google maps.

Julius Erlandsen and his mother, Louise Aubinger Erlandsen, shared an apartment at 138 East 94th St. in Manhattan since at least 1905. Louise died in 1928, and then Julius moved to 3758 84th St. Jackson Heights, Long Island City, Queens, N.Y.

Julius Erlandsen, in the 1930 U.S. Census, living at 3758 84th St. Jackson Heights, Long Island City, Queens, N.Y.

After leaving 172 Centre Street in 1932, Julius Erlandsen sought out a smaller workshop space, which he found at 331 West Broadway. Diminished sales during the Depression, as well as advancing age likely influenced Julius’ decision to downsize. Erlandsen remained at 331 West Broadway into the 1940s

Julius Erlandsen, Toolmaker, 331 West Broadway, New York City. From 1940 Manhattan Telephone Directory.

Julius Erlandsen was living at 37-58 84th St. in the Queens borough of New York City at the time of the 1940 census. He listed his vocation as a machinist, specifically making piano tools. Julius also declared that he worked a full 40 hour week previous to the census interview, and that he worked a full 52 weeks in 1939.

Based on the limited volume of piano supplies produced during the Great Depression, I’d speculate that Julius was working alone or with one assistant.

Julius Erlandsen was the most prolific of all the New York piano toolmakers, when all of his specialized tools were taken into consideration.

For the 1950 census, Elizabeth Erlandsen, age 40, was listed at 37-58 84th St., Apt. 31. Elizabeth was not home during the initial tally, so this was a follow-up visit. Julius Erlandsen was not counted, but he was likely still living there. I am not sure how Elizabeth was related to Julius, although she was the right age to have been his daughter. Julius Erlandsen was known to be single, and I am not aware that he had any acknowledged children. It was also not outside of the realm of possibility that Julius Erlandsen married Elizabeth, a much younger woman–although, I have not found a marriage document for Julius and Elizabeth. With Elizabeth as head of the household, it does make me wonder if Julius was ill or disabled at this point. When the 1950 census is indexed (2022) perhaps Julius will show up in another location, such as Roslyn, Nassau County, Long Island, N.Y., where he died. In Julius’ obituary, however, 3758 84th St. was still given as his address.

After World War Two, the participation of Hammacher Schlemmer within the piano supply industry was fairly inconsequential. The few H. S. piano tools that were made during the period between 1946 and 1954 consisted of stationary tuning hammers, and a few other basics.

Hammacher Schlemmer stationary tuning hammer, with cross-hatch knurling on shaft. Post War, c. 1946-1954. Crisp machining on a budget tool.

Julius Erlandsen used cross-hatch knurling on some of his earlier tuning hammers.

A handful of small production runs would have been all that was was necessary for Hammacher Schlemmer’s requirements in their Piano Supply Division between 1946 and 1954, something that a reasonably healthy older man, like Julius Erlandsen, could probably accommodate.

Another possible scenario would be that Julius Erlandsen retired earlier, in the 1940s. And when Julius gave notice to Hammacher Schlemmer, they pre-ordered a significant quantity of piano tools, in an effort to forestall having to search for the next specialized machinist.

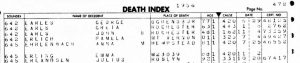

Cause of death code No. 331 from “International Classification of Diseases,” Revision 6 (1948), was Cerebral Hemorrhage, or stroke. A stroke also caused the death of Julius’ brother, Oscar.

Julius Erlandsen’s obituary in the New York Times on Oct 24, 1956, just a few weeks away from his 90th birthday. He was born on December 5th, 1866.

Oscar Erlandsen Sr. died in 1943; this was his son Oscar Napoleon Erlandsen Jr. (1907-1995), an aircraft engineer. Mrs. Albert Mackie was Amy Louise Erlandsen (1901-1996).

Legacy

An overview of the Erlandsens’ contributions to the piano supply industry are included in “New York Piano Planes, Part II.”

Erlandsen tuning hammers continued to be used for many decades into the 20th century: not as antiques, collectibles, or period pieces, but as working tools with their own inherent merit. A review of “The Piano Technician” uncovered photos of Erlandsen tuning hammers in use to at least 1960.

Napoleon Erlandsen original extension tuning hammer, introduced in 1863; shown in use in a Wurlitzer advertisement. From “The Piano Technician,” October, 1948.

Julius Erlandsen extension tuning hammer, with September 27th and December 13th, 1904 patents; shown in advertisement for the Winter Musette. This ad ran from 1955 to 1960. From “The Piano Technician,” October, 1956.

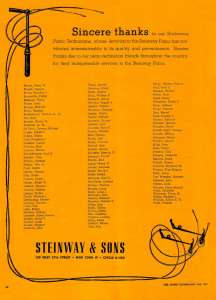

Steinway Piano Technicians’ roster, with Erlandsen Stationary Tuning Hammer. From “The Piano Technician,” July, 1947.

Some of the notable individuals here would include Michael Bogyos, Fred Drasche, Walter Drasche, (I worked with Walter’s son Steve in the early 1980s), Bill Hupfer (Head Technician at C.&A. until c. 1965), Bill Pardy (Bill came out of retirement in 1984, and worked a few more years at Steinway Hall), and Morris Schnaper (an exceptional tuner).