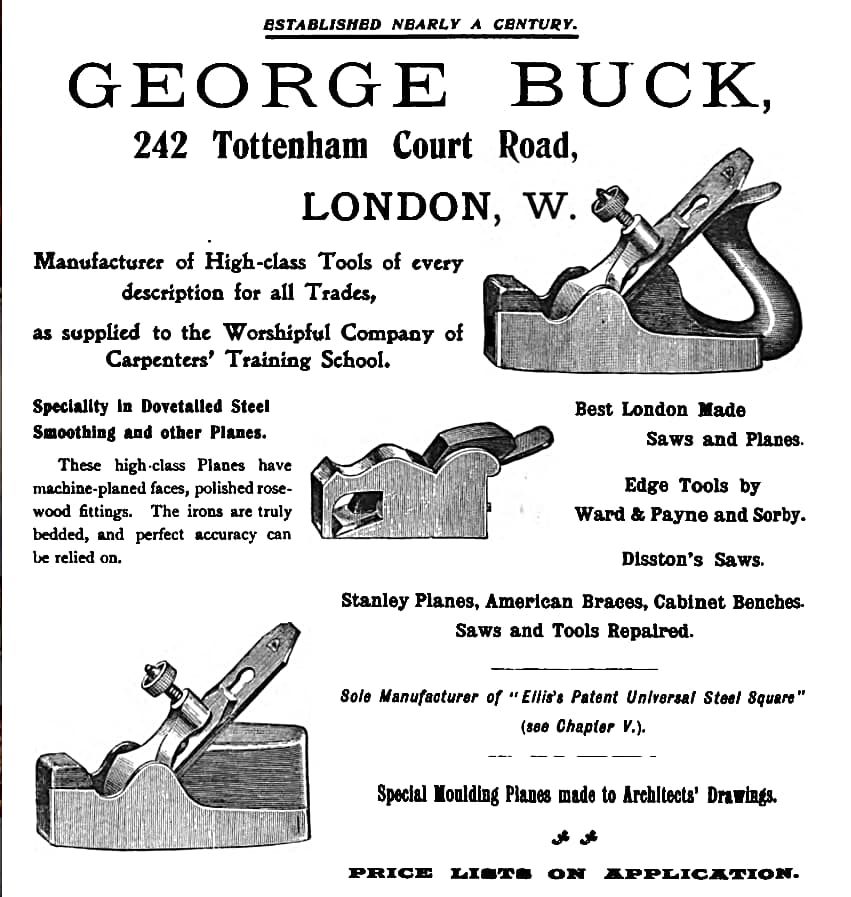

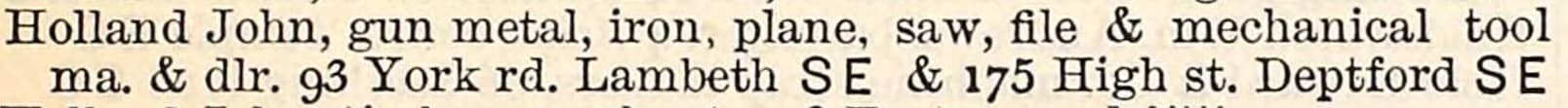

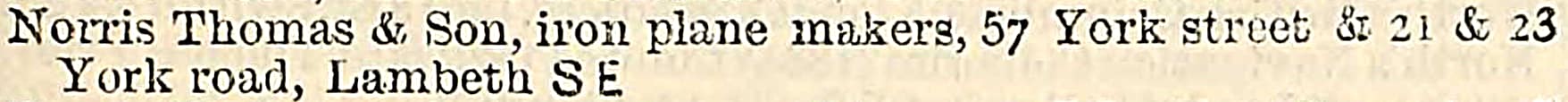

George Buck ad in “Modern Practical Joinery” by George Ellis, 1908. They offered bow drills, planes, tuning, voicing, and regulating tools to the piano trade. Specialized Buck piano tools can be found throughout this website; however, this page is focused on Buck mitre planes. For planes, George Buck carried the revered Norris line, but they put their own attractive mark on their tool merchandise. Buck has carried other infill plane makes during their long tenure in business, including Towell, Spiers, Holland, Slater, and Miller.

One of George Buck’s specialties was providing hand tools for the London Piano industry. Buck advertisement in “The Pianomaker” for May 1914.

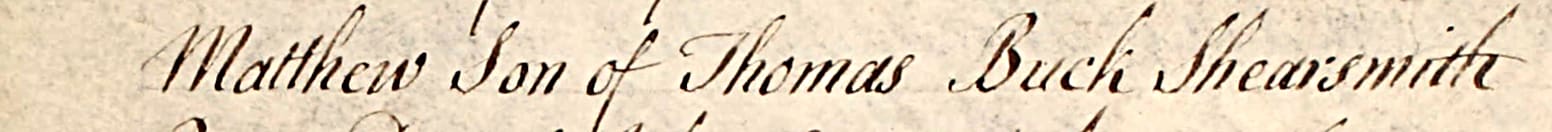

Matthew Buck (1776-1844) Father of Three Buck Tool Dealers

Matthew Buck was Baptized 8 November, 1776, at the Cathedral of Saint Peter and Paul, in Sheffield, York, England, and his parents were Thomas Buck, a “Shearsmith” (1748-1785) and Ruth Ashton (1746-1780). In Sheffield, Matthew Buck learned the metalwork necessary to make saws and files; since Matthew’s father Thomas died when he was only 9, he would have apprenticed with one of the many other Edgetool makers in Sheffield.

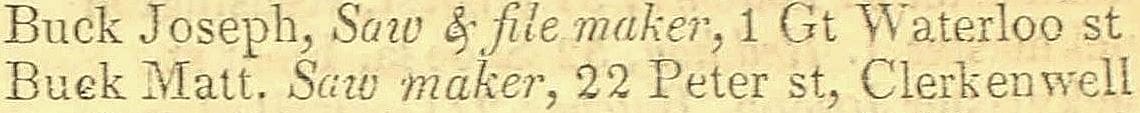

Matthew Buck became a saw and filemaker who worked out of 22 Peter Street, Clerkenwell from before 1807, until after 1833. Even though Matthew remained a modest tradesman to the end of his life, all of his progeny who ran Buck retail stores called themselves “saw & filemakers.”

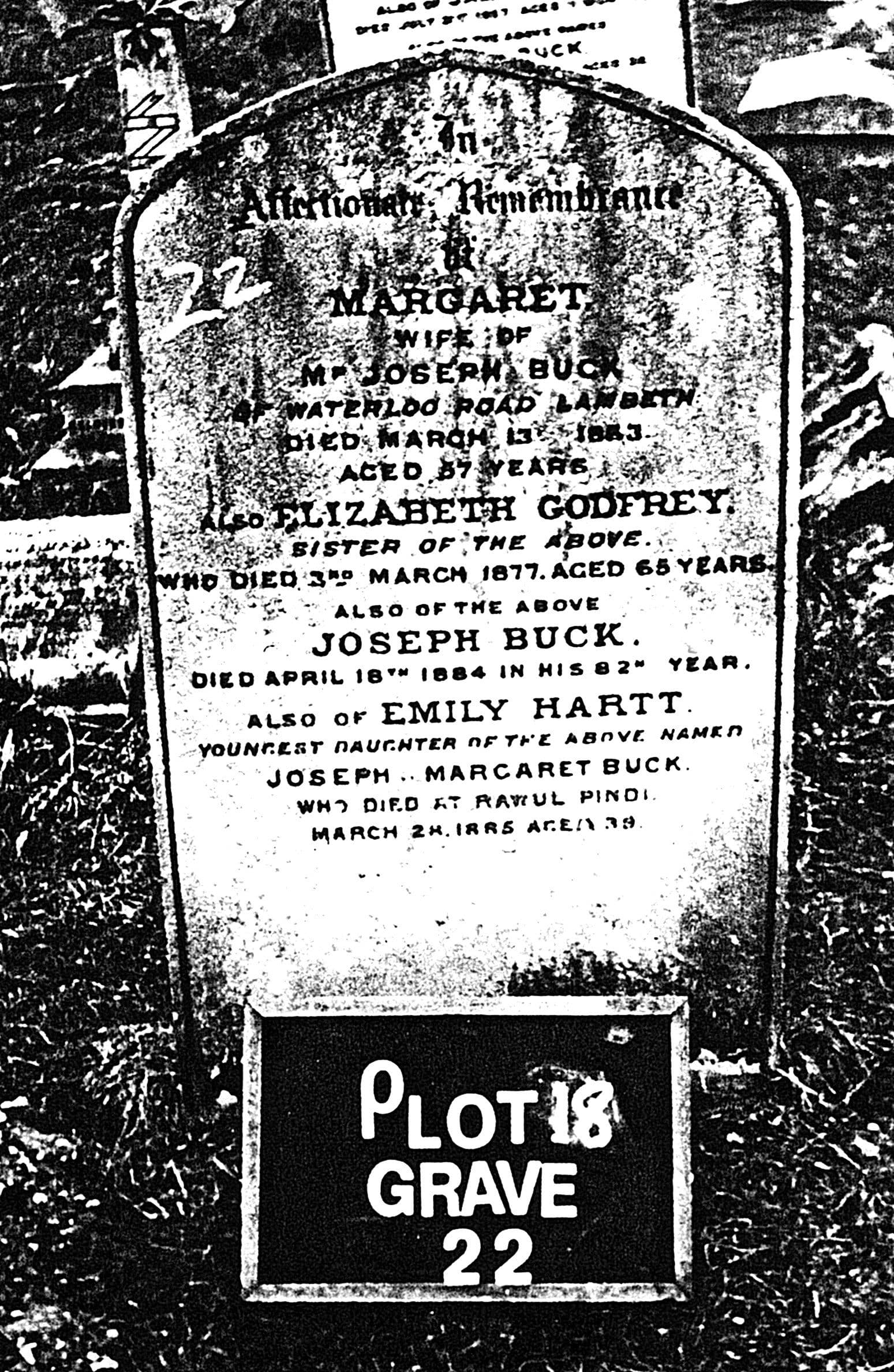

Matthew and Mary Buck had five children: Joseph (1802-1884) born at Westminster, London, England and George (1805-1865), Ann (1807-1895), James (1809-1810) all born at Clerkenwell, Middlesex, England and Elizabeth (1810- ) born at St Andrew, Middlesex, England.

Matthew Buck, Peter St., Clerkenwell, in the 1808 Land Tax Records.

Matthew Buck, in the 1832 Electoral Register.

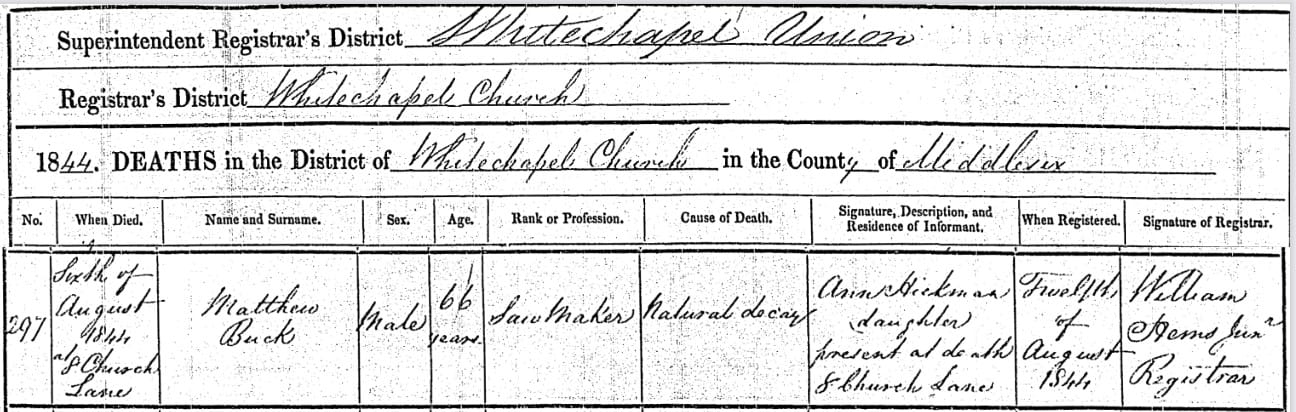

Matthew Buck passed away on August 6, 1844 at 8 Church Lane (now White Church), London, England. 8 Church Lane was the business address for Buck & Hickman at that time, and Ann Hickman was present at the time of his passing. Matthew was interred near his wife in St. John-at-Hackney Churchyard at Hackney, London Borough of Hackney, Greater London, England.

The Bucks: A Family Affair

The Buck extended family became a large tool dynasty with three separate businesses, two of which continue to trade well into the 20th century: Joseph Buck (1802-1884), whose business later branched off into Buck and Ryan, George Buck (1805-1865), and Ann Buck (1807-1895), who married John Hickman Sr. (1806-1847), and then established Buck & Hickman in 1832. In their early years, these businesses were quite intertwined.

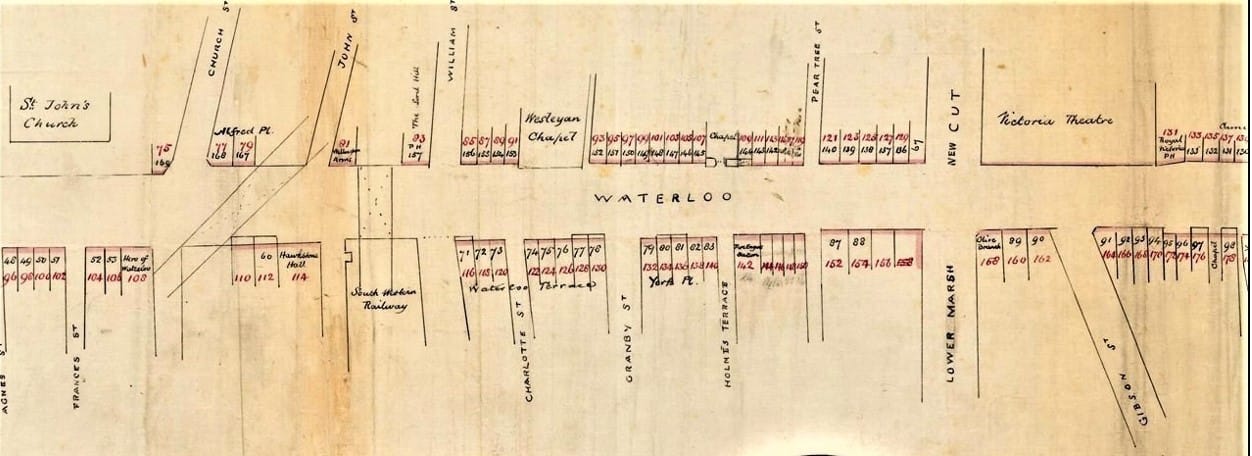

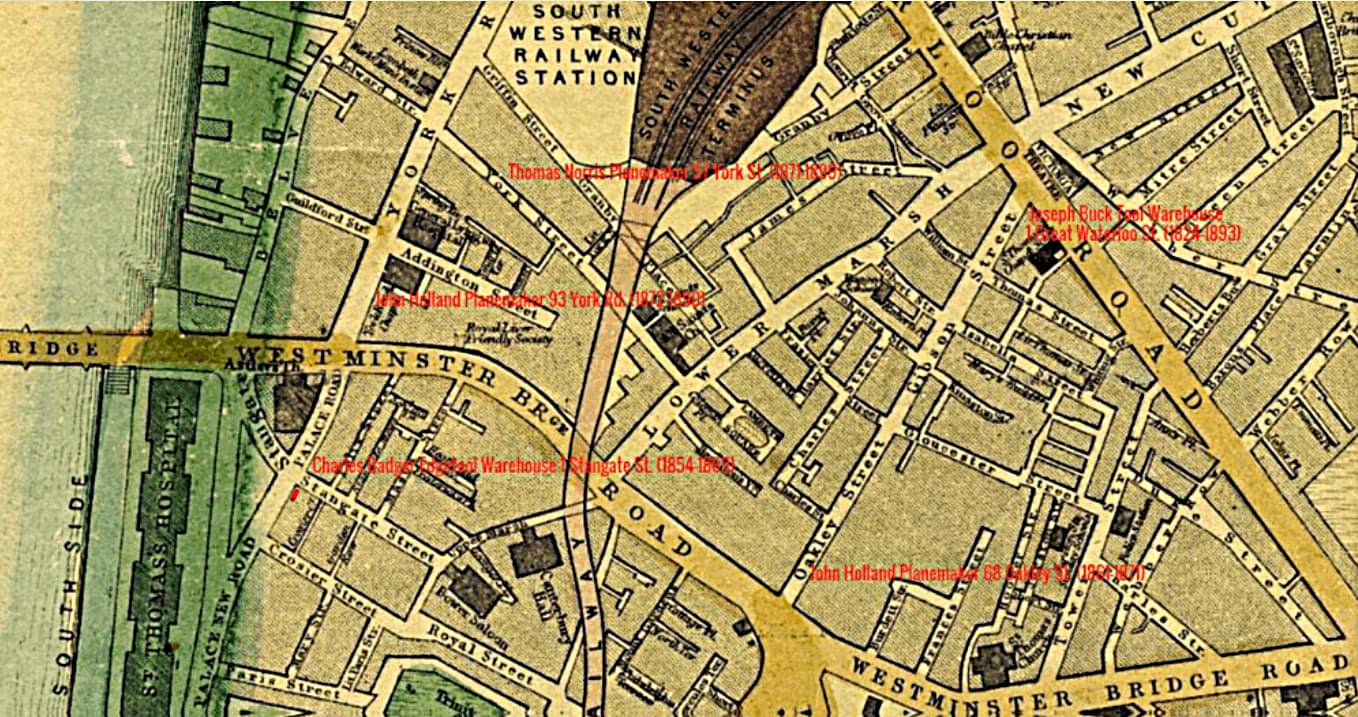

Horwood’s Plan of London, 1819 Edition, excerpt of Lambeth, with Great Waterloo St. and Gibson St.

The 1825 London Trade Directory would have been sent to print in the fall of 1824, when George’s older brother, Joseph Buck was only 22 years old. Clearly, Joseph had access to some start up money. Joseph expanded to other addresses in just a few short years: 1 Gibson St. Lambeth, 1826; 245 Tottenham Court Road, 1831; 124 Newgate St., London City, 1834.

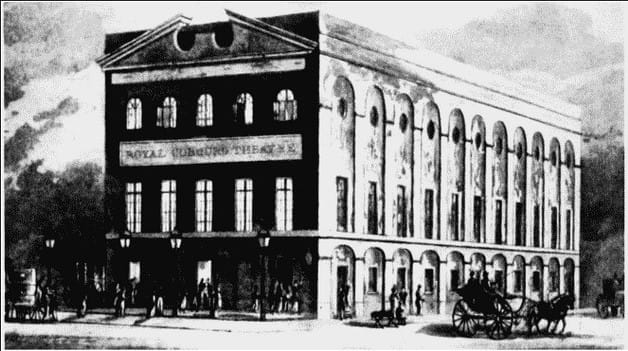

1 Gibson Street and 1 Great Waterloo Street were either very close to each other, or they were indeed the same location. The Royal Coburg Theatre (est.1818), later renamed the Victoria Theatre (c.1833), was listed as across Waterloo Rd. from the J. Buck warehouse in later directories, circa 1843-1890. Various street numbers on Waterloo St./Rd. were renumbering rather than actual moves: 1 Great Waterloo St./1 Gibson St. (1824-1843); 91 Waterloo Rd. (1844-1863); 164 Waterloo Rd. (1867-1893).

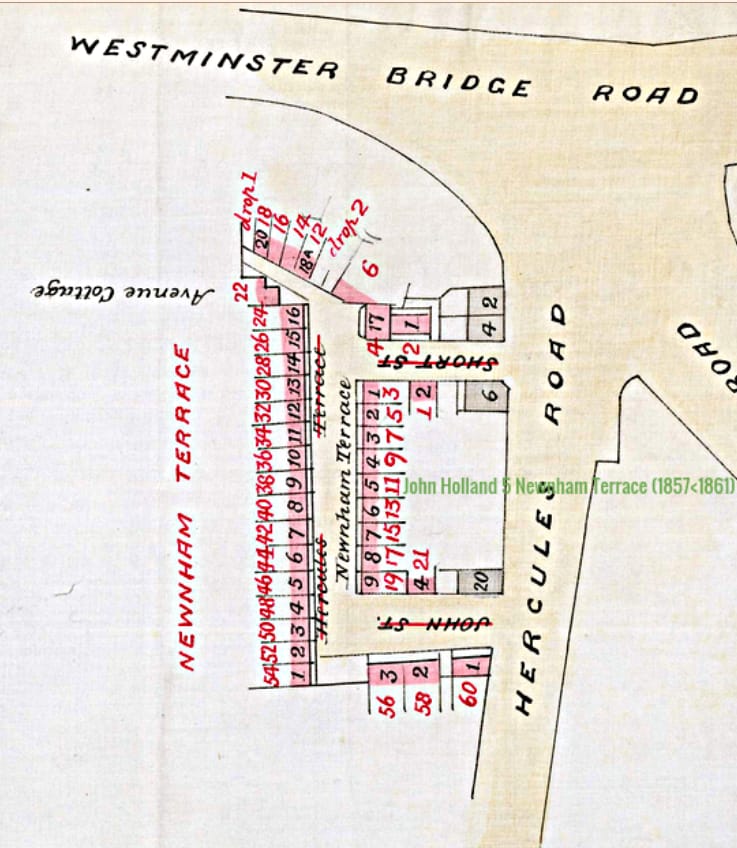

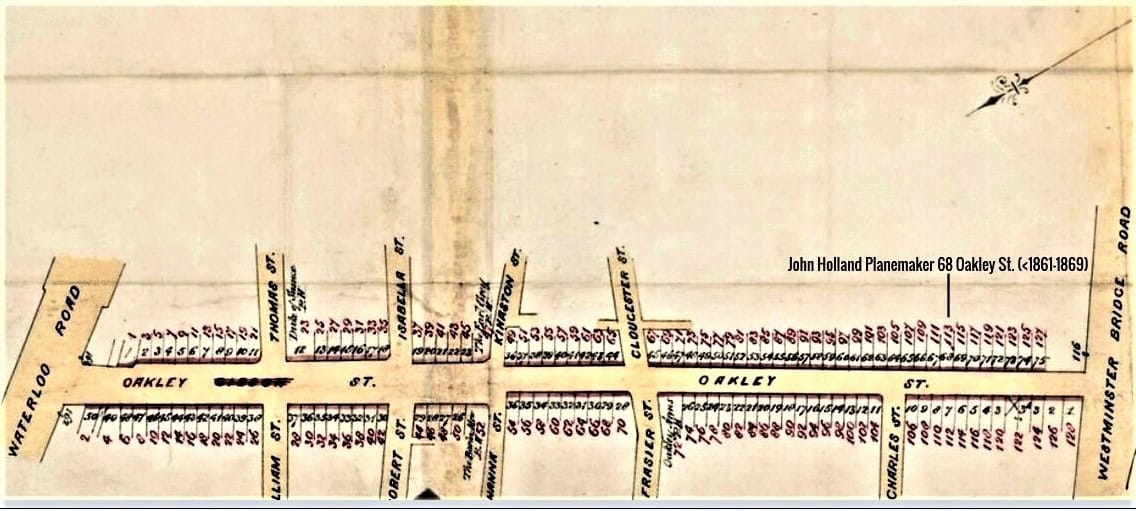

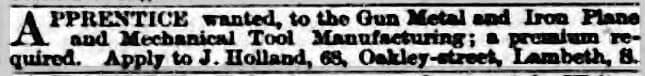

Oakley Street ran into Gibson Street. 68 Oakley Street was planemaker John Holland’s address from 1861 to 1871. This proximity likely fostered a working relationship between John Holland and Joseph Buck.

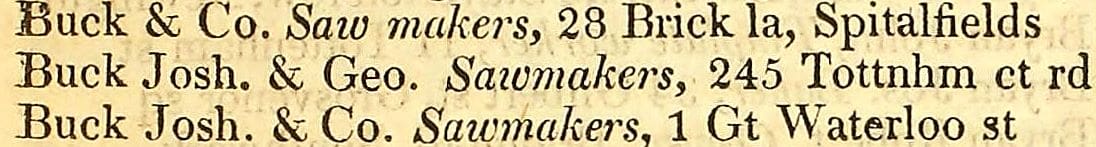

“I. Buck” (Joseph, 11 July, 1802-18 April, 1884), at 1 Great Waterloo Street, Lambeth, in the 1825 London Trade Directory.

Looking Glass Curtain, Royal Coburg Theatre, 1822.

Royal Coberg Theatre in 1826. Image from British History Online.

Waterloo Street Renumbering Plan, showing 164 Waterloo St., Joseph Buck Tool Warehouse. From Lambeth Archives. Street numbers on Waterloo Rd./St. were reconfigured rather than Joseph Buck moving the warehouse.

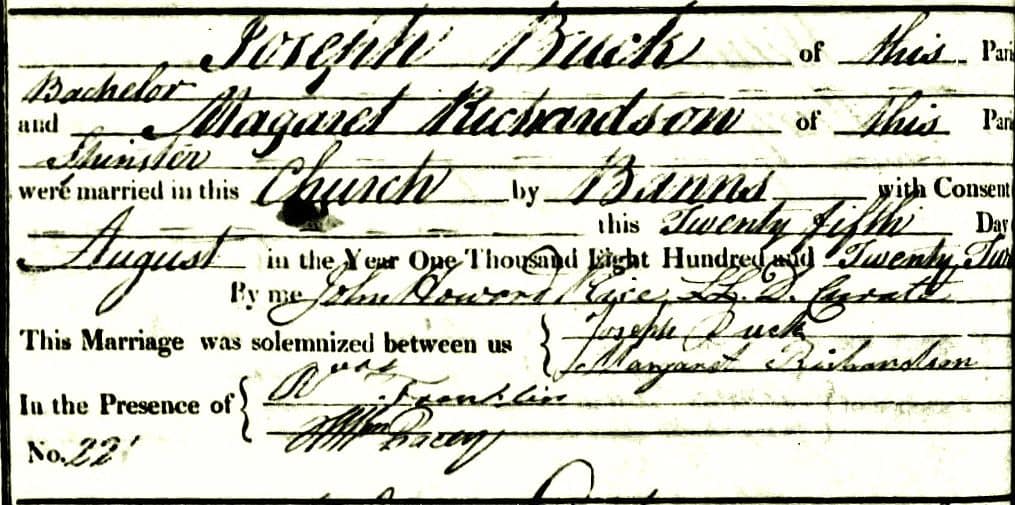

Joseph Buck married Margaret Richardson (1803-1863) , 22 August, 1822, at St. Luke’s, Finsbury.

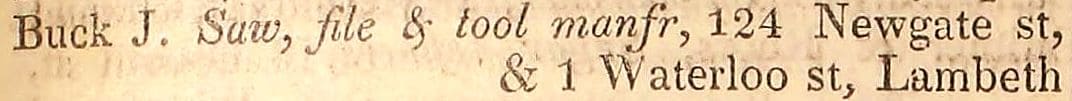

Joseph Buck, 124 Newgate St., London; 1 Waterloo St., in Robson’s 1835 London Trade Directory.

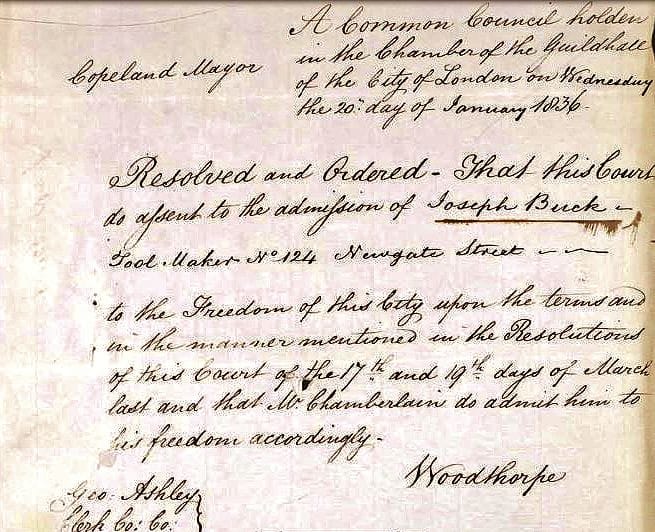

Joseph Buck was awarded “Freedom of the City,” admission papers on 20 January, 1836.

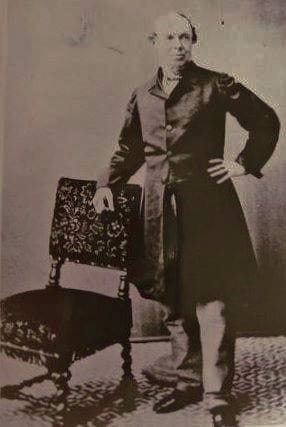

Joseph Buck, circa 1860.

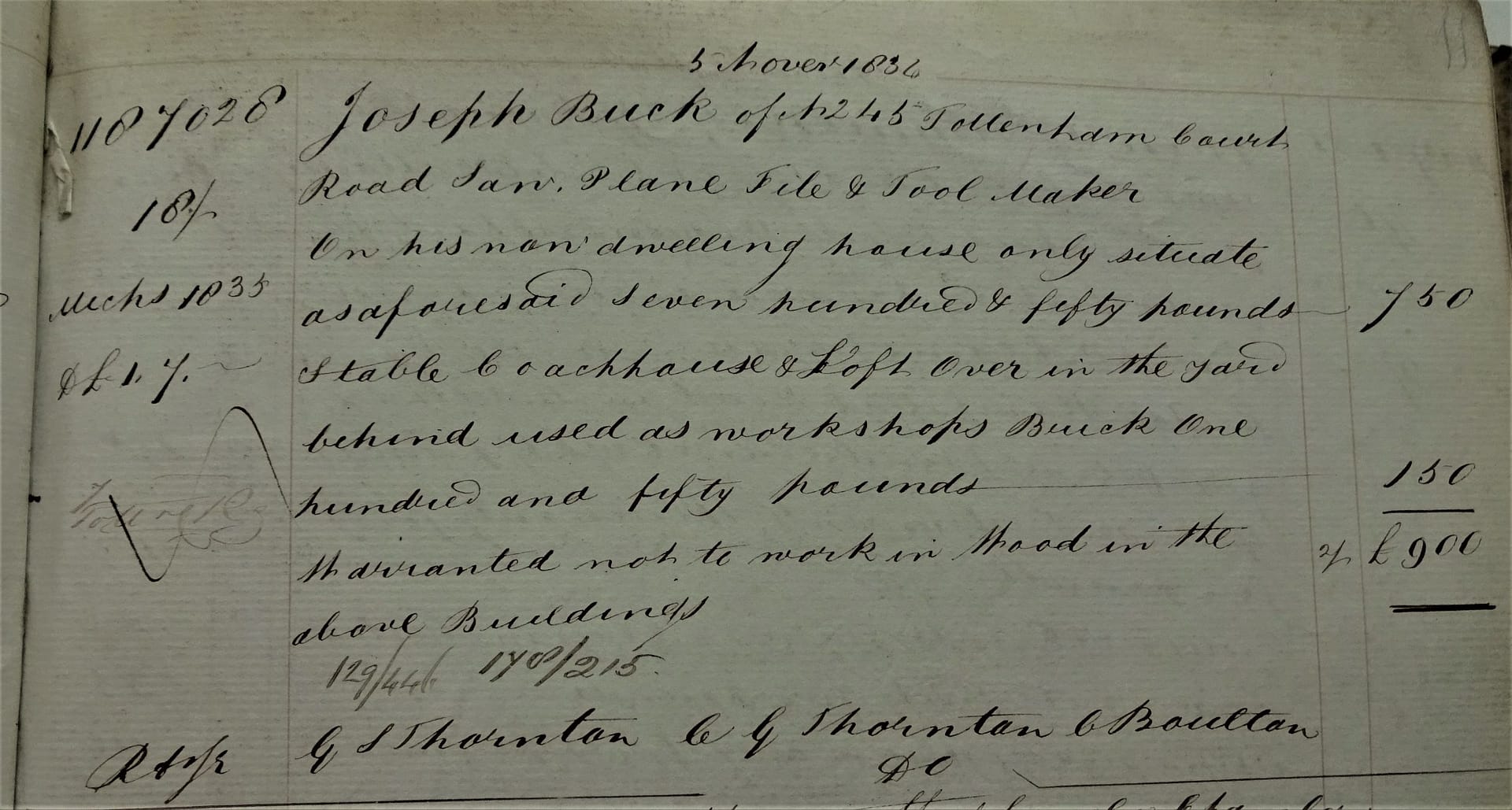

28 Brick Lane, Spitalfields may have been the actual saw making facility long searched for. This is the earliest document for Buck at 245 Tottenham Court Road that I have found to date.

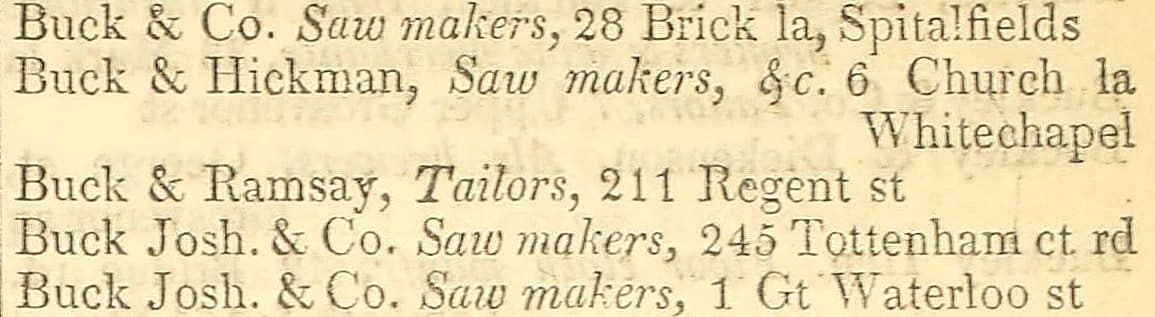

The Buck Clan, Robson’s 1833 London Trade Directory.

Last known listing for Matthew Buck, in Robson’s 1833 London Trade Directory.

The main building and residence at 245 Tottenham Court Road was insured for £750. “Stable, coach house, and loft in the yard behind used as workshops. Brick £150. Warranted not to work in wood in the above buildings.”

Sun Insurance Company must have had a lot of power, which enabled them to write a deal like this.

A later Sun Insurance document from the same policy, referred to the business as “J. Buck, now George Buck of 245 Tottenham Court Road,” on 20 September, 1854.

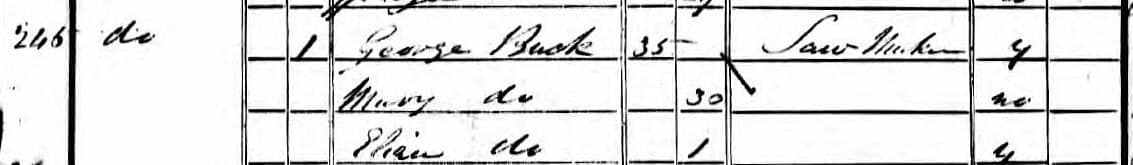

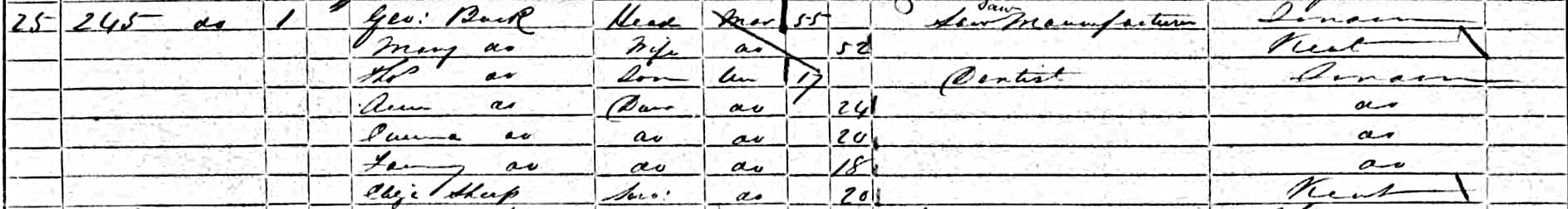

George Buck, 1841 U.K. census, 245 Tottenham Court Road, “Saw Maker.” George and Mary were living together at 245 Tottenham Court Road, with their third child, more than 11 years before their marriage to each other.

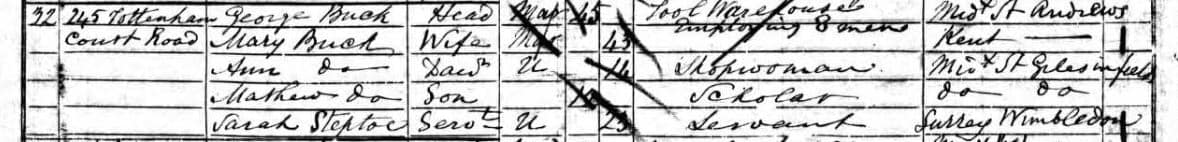

Geo. Buck, 1851 UK census. “Tool Warehouse employing 8 men.” 245 Tottenham Court Road. At the time of the 1851 census, George and Mary Buck and their children were living in the housing quarters above the tool warehouse which was on the ground floor.

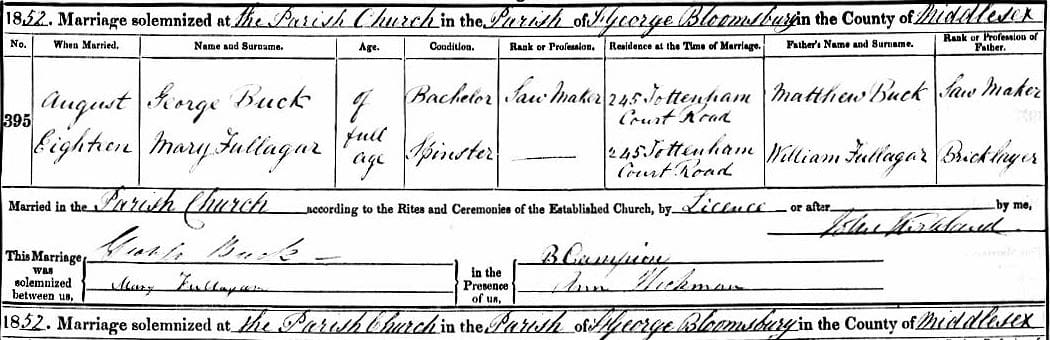

George Buck marriage to Mary Fullagar, 18 August, 1852. William Fullagar also lived at 245 Tot. Ct. Rd. Typical of the mid-19th century, George Buck had a large family: George married Mary Fullagar and they had at least nine children. Or more accurately, George and Mary had a lot of children, then they got married. “Of full age’ (over 18).

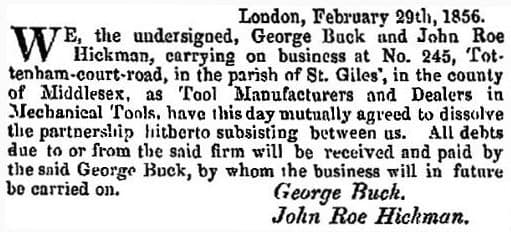

Dissolution of a short-lived partnership: between George Buck and John Roe Hickman Jr. (1829-1904). John Roe Hickman Sr. was a printer by trade. From the London Gazette, 29 February, 1856.

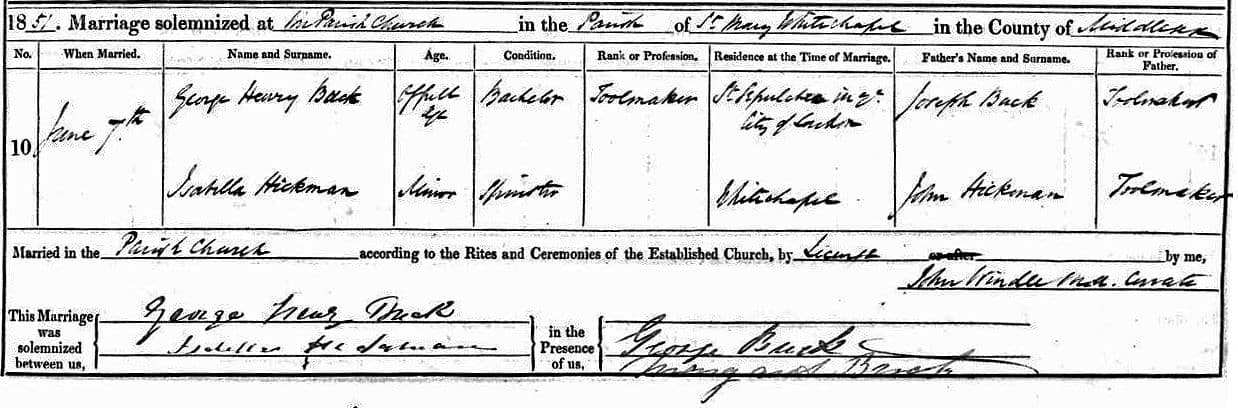

Not to be confusing, George Henry Buck (1825-1891), son of Joseph, married his first cousin, Isabella Hickman. George Henry took over the business of Richard Nelson at 122 Edgeware Road circa 1850. In around 1893, George Ryan, a manager for George Henry since 1870, bought the business and it became Ryan & Buck. By 1910 the name was switched to Buck & Ryan. The Joseph Buck company, however, continued to trade separately, under the ownership of Tyzack until liquidation in 1922.

John Roe Hickman Sr. was a printer by trade.

George Henry Buck married Isabella Hickman at St. Mary’s, Whitechapel on 7 June, 1851. George Henry and Isabella had at least six children. Both fathers declared their profession as “Toolmakers.” in this marriage document.

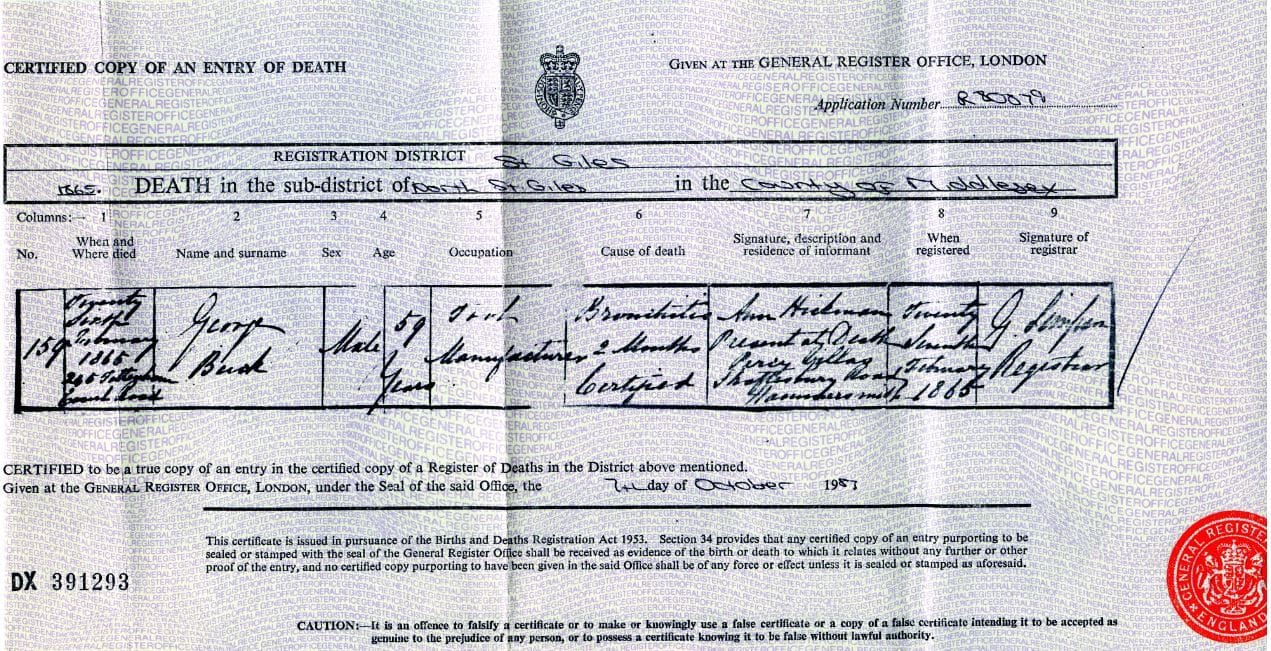

On 26 February, 1865, George Buck passed away at age 59. Many of the best years for George Buck’s business were still ahead of them, and their successors actively maintained the tool business into the 1980s.

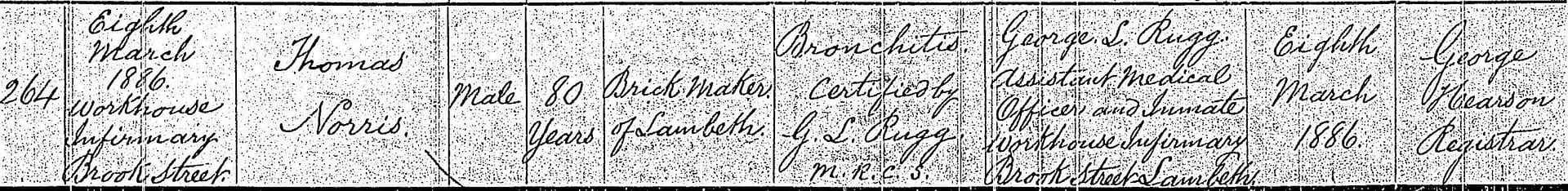

George Buck, death certificate. Died 26 February, 1865, from bronchitis. Ann Hickman present at death.

Buck left a good legacy for his wife Mary Fullagar.

It was George Buck’s tool warehouse, which was most closely associated with fine infill planes and piano tools from 1838 to World War One. Joseph Buck, however, did sell Towell planes in the 1830s and ’40s, then they sold some other makers’ planes, such as Holland’s in the 1860s and 70s. Buck & Ryan sold some Norris planes in the 1920s and ’30s.

Proprietary stamps for “BUCK” metal planes rarely included a first initial after 1850 or so even though George Buck would usually stamp his Tottenham Court Road address on the bridge or lever cap. This differed from items marked specifically “G. BUCK,” such as bow drill stocks, saws, specialist piano tools, chisels, braces, and wooden planes. Since a fair amount of capitol was tied up with metal infill planes, it would be a reasonable assumption that all three Buck businesses participated in selling these products by pooling their money.

Joseph Buck, in the Probate Index, died 18 April, 1884.

Probate Index (continued).

£23,000 in 1884 equals about $3,500,000 in today’s dollars. On average, businesses which sold tools as a concerted and organized effort, along with making tools, or dealers who traded in tools exclusive from making them, did better financially than those who primarily focused on making tools.

Gravestone of Joseph Buck, West Norwood Cemetery and Crematorium, West Norwood, Lambeth.

John Roe Hickman Jr., (1828-1904).

£65,847 in 1904 would be more than $10,000,000 in today’s dollars.

For comparison, Sheffield edgetool maker William Butcher died with a fortune of £100,000 in 1870. Scottish-born steel magnate Andrew Carnegie amassed a fortune of $380,000,000 or $309 Billion in today’s currency.

Joseph Buck’s 1912 Pianoforte and Organ Builders’ list offered 5 sizes of mitre planes, 3 types of thumb planes, and 2 sizes of panel planes. All of the mitre planes and at least two out of three of the thumb planes would have been made by Norris, because that was where Buck was sourcing most of his infill planes just before The Great War. What planes were included, as well as the planes that were omitted, provide insight into which actual planes were in demand for purchase within the piano industry. Following logically, this gave an indication around what planes were used more and what was used less. No smooth planes were included in this list for pianomakers, which could indicate that bevel up planes were used in common practice for a wider range of tasks, including at least some smoothing.

The Bucks as Saw Makers

All census information, except the address were obtained by the resident’s response to the census takers’ questions. Are they the last word in defining the vocation of these planemakers? Not necessarily, but given the relative dearth of information for these individuals, it’s one of the best references we have under the circumstances. The working classes and skilled craftspeople of the 19th century and earlier were not generally people of letters, so there is less information to work with than the more academically educated classes. They were smart in other ways.

Illiterate “X” signature on early mitre plane. Many early wills were signed with an “X” not unlike this example.

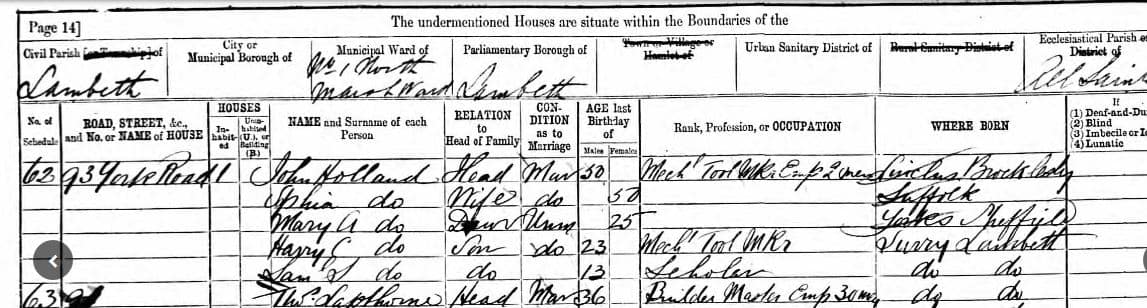

George Buck and family, “Saw Manufacturers,” U.K. census, 1861.

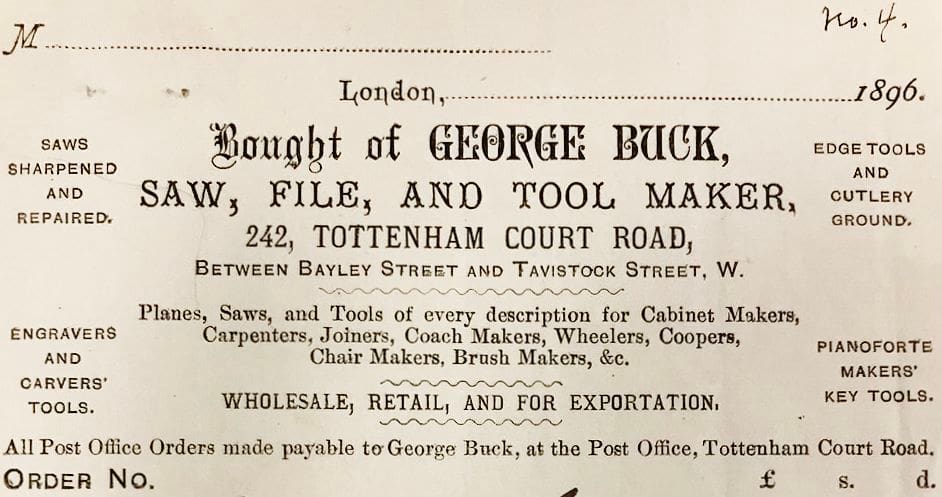

Here is an example of this census reporting issue. George Buck was known as a tool dealer rather than a maker, but in 1861, he described his business as a “Saw Manufacturer.” After all, George’s father Matthew made saws, and George must have possessed the know-how to make saws, at the least. Another large tool dealer, Moseley, also described their business as a manufacturer of tools, and for a number of years, they had a horse mill at the rear of their premises. I could find no direct evidence to date of an in-house shop at 245 Tottenham Court Road making tools from scratch. George and Joseph Buck, however did have workshop space behind the 245 Tottenham Court Road in three areas: a stable, coach house, and loft. That would have been enough combined space to make tools, but it was unclear if Buck actually made tools, and ignored the restrictions around working in wood that were mandated by the Sun Insurance Company. Perhaps George Buck owned an off-premises saw making shop we do not know about.

Consistently during George Buck’s life, and after his death, the Buck business was listed as a saw maker. Multiple sources for this lends credibility that the G. Buck firm actually did make saws, and possibly some other tools such as files. On the other hand, they could have been sold on the idea of being recognized as a maker of tools. At various times, all of the Buck firms listed their business under “saw, file, and plane makers.” This included Joseph Buck, Buck & Hickman, and George Henry Buck. Patriarch, saw and filemaker Matthew Buck (1776-1844) must have exerted a lifetime influence on his children.

Illustrations showed phases of saw making: cutting, grinding, and punching teeth with a fly press. Not included was a furnace.

George Buck Invoice header from 1896.

Making Saws. From “The Working Man,” 3 February, 1866.

George Buck’s siblings also identified themselves as “Saw and Toolmakers.”

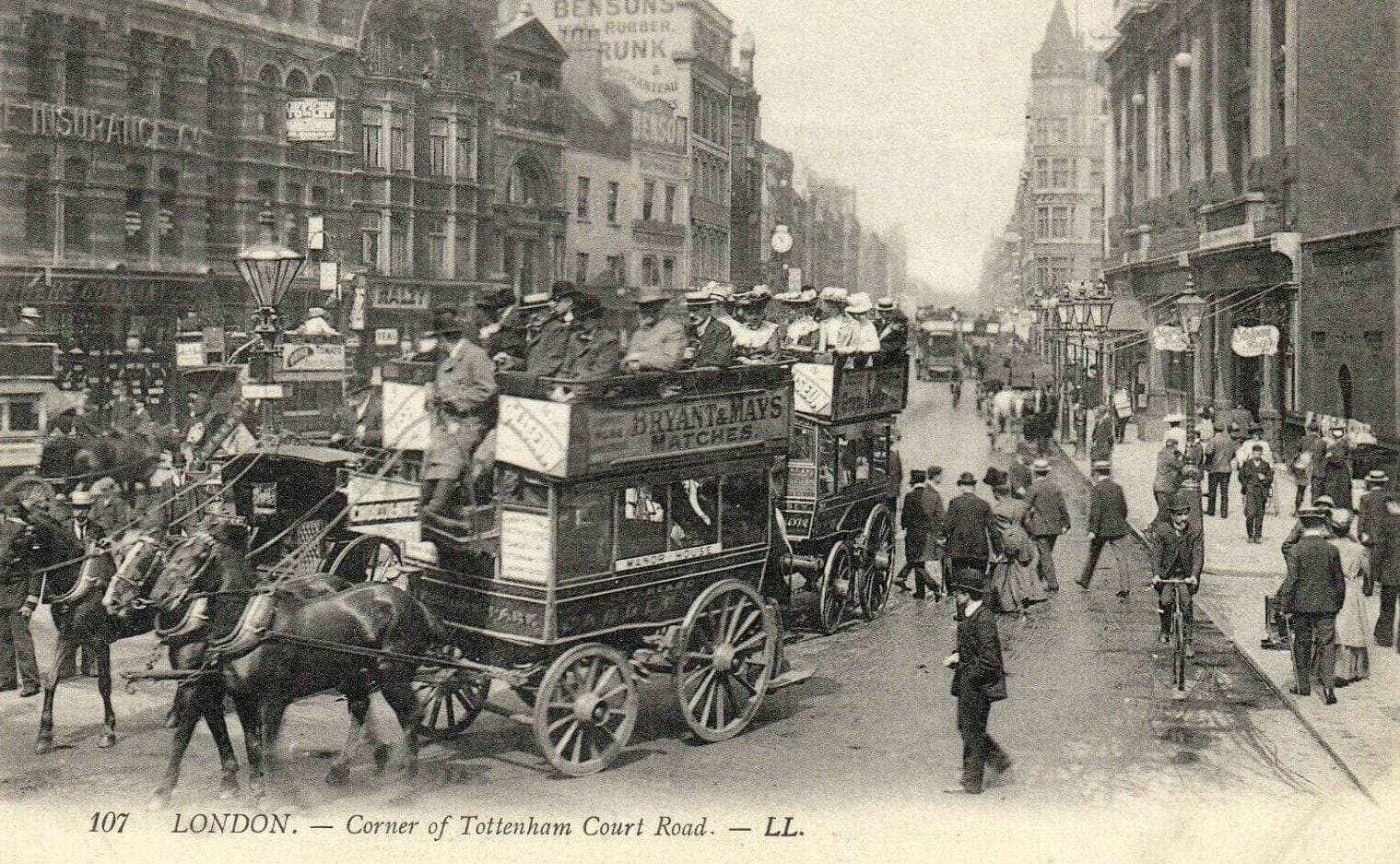

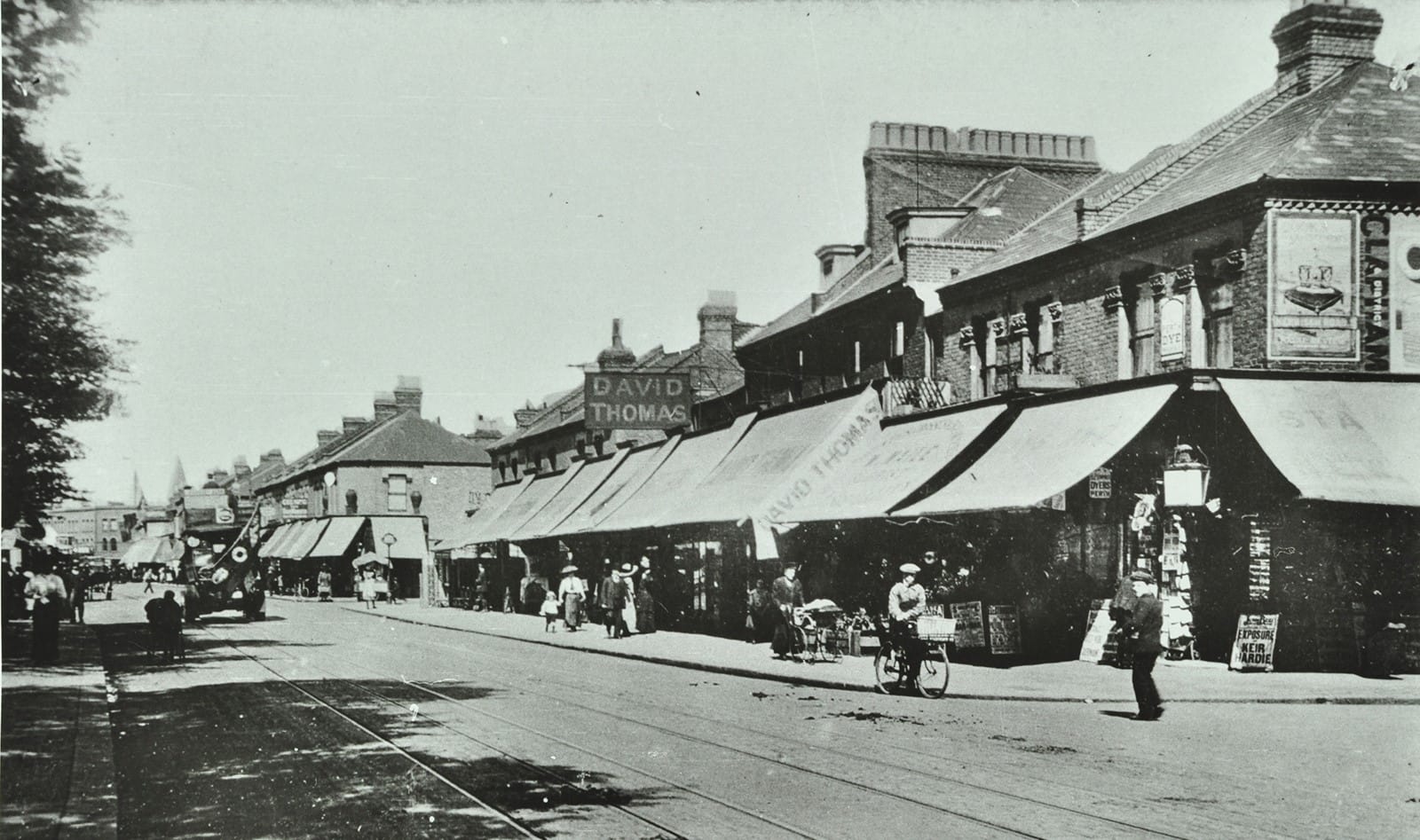

Tottenham Court Road street scene in the 1890s.

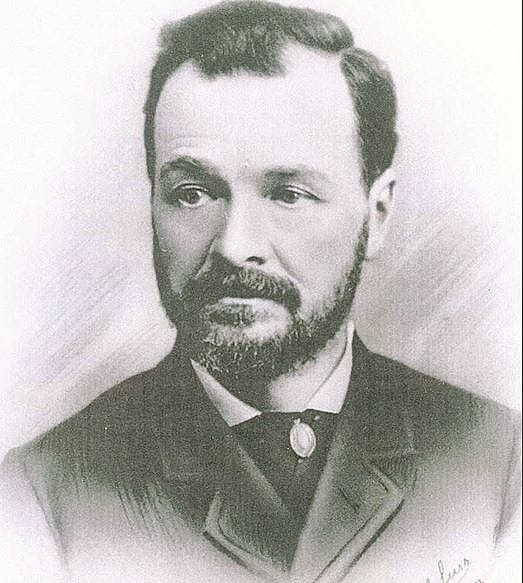

George Buck in sartorial splendor. (1805-1865).

Iron planemaker Richard Bywater, P.O. Directory 1805; 72 Tottenham Court Road (<1794-1807); 218 Tot. Ct. Rd. (1808-1814>). Much earlier, but worth inclusion.

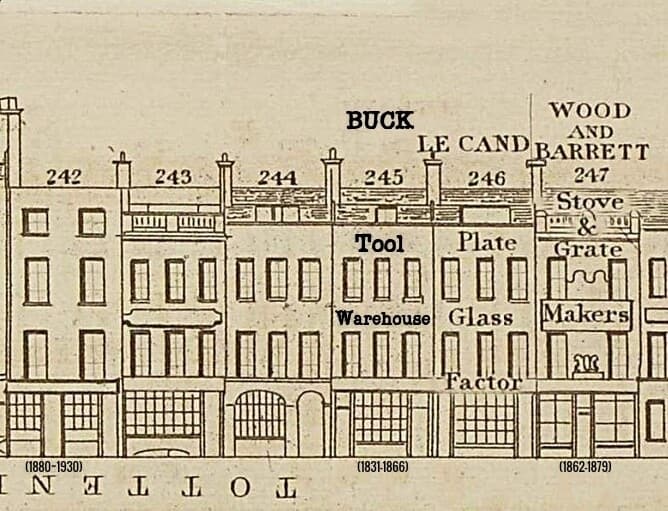

Section of a detailed London map, by the Ordnance Survey in 1893-96. George Buck’s tool warerooms at 245, 247, 242 Tottenham Ct. Rd (1831-1930; 21 Goodge St. 1938-80>), and his neighbors in allied trades during the 1860s-90s: J. & J. Goddard, piano supplies, 68 Tottenham Court Road (1842-1968); Richard Reynolds, piano ironmonger/toolsmith, 4 Upper Rathbone Place (<1880-1895; in Hammersmith to 1940); George Kerr, planemaker, 36 Store St. Bedford Square (c. 1864-65.

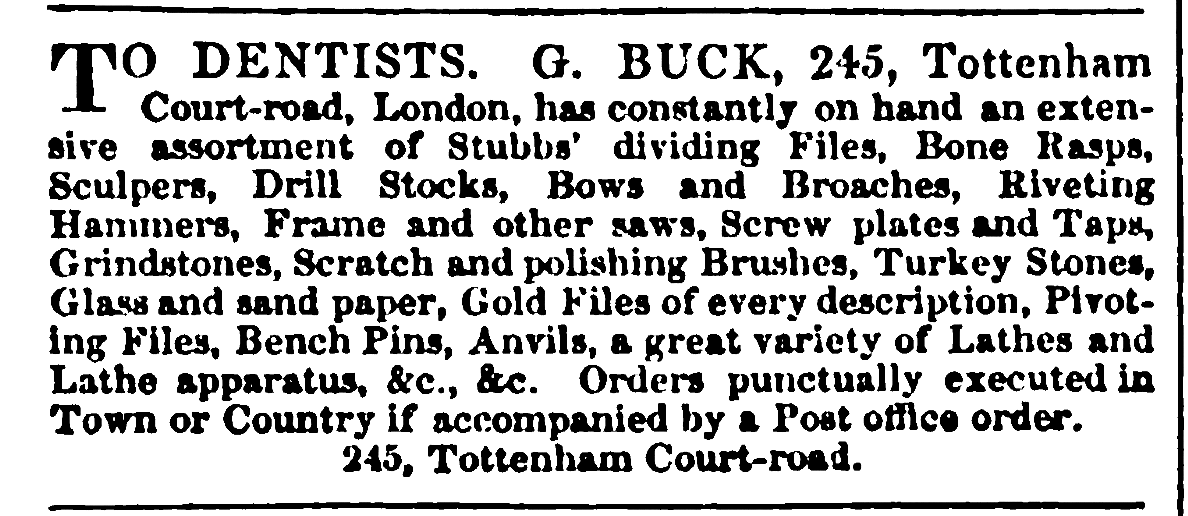

G.Buck ad in “The Forcepts; Journal of Dental Surgery,” 13 July, 1844. From the establishment of his business in 1831, George Buck supplied a wide range of trades and professions. These dental instruments make me appreciate living in the 21st century.

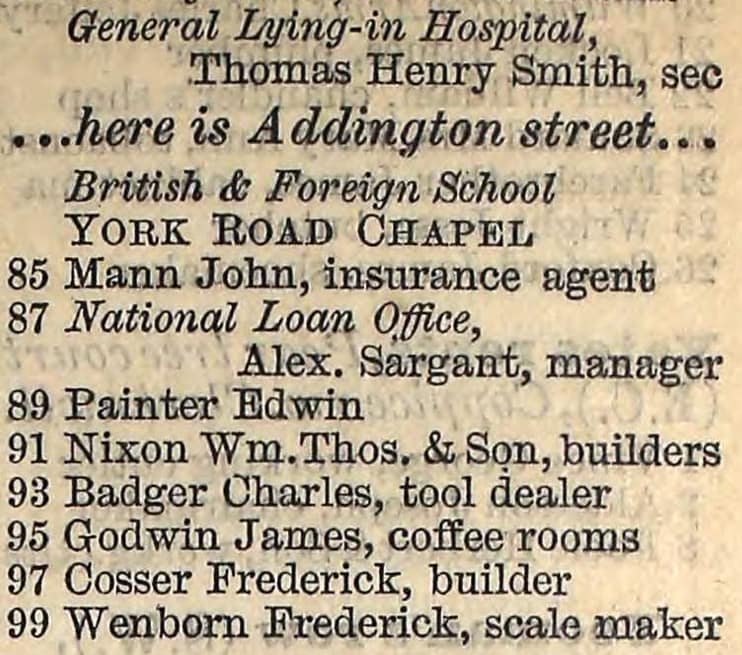

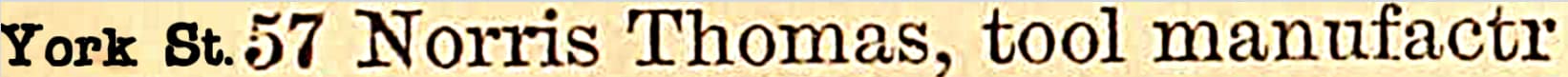

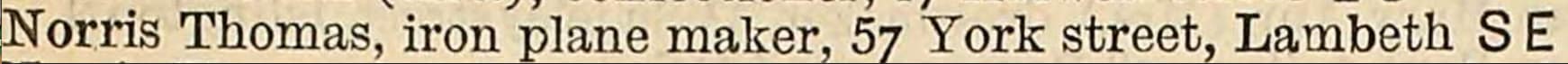

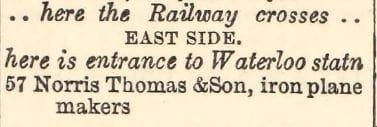

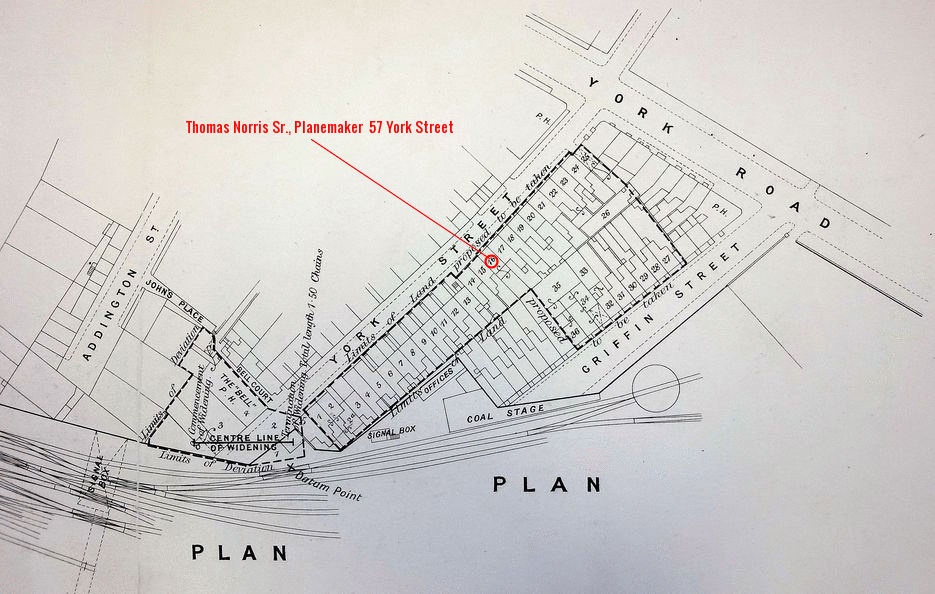

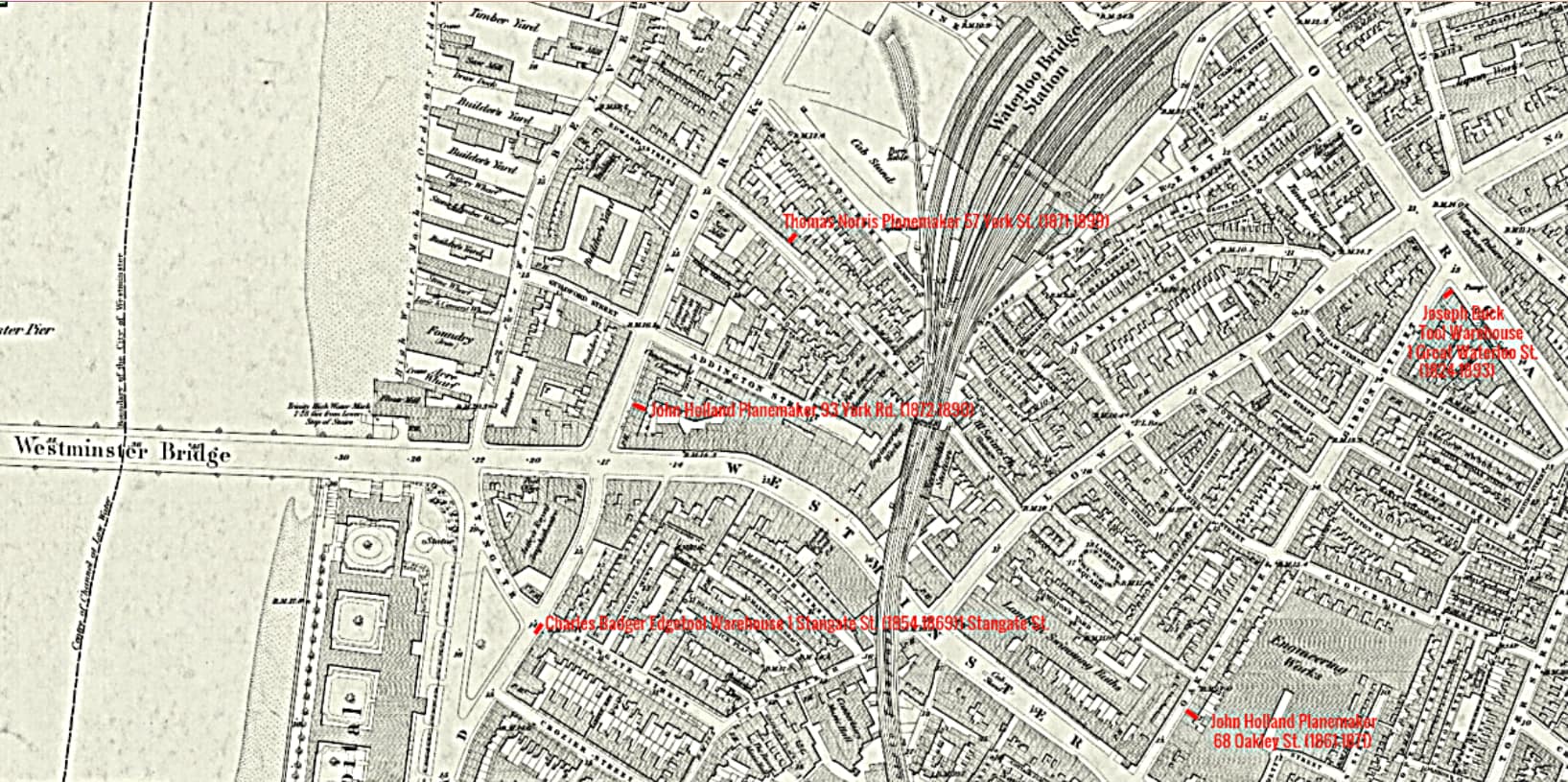

E. Weller’s 1868 London Map, section with Lambeth. Map section shows the following: Joseph Buck, brother of George Buck, b 1802. planemaker and dealer, 164 Waterloo Rd. (1824-1893); Charles Badger, iron planemaker, 1 Stangate St. (1854-68) 93 York Rd. (1868-1869); John Holland, planemaker, 68 Oakley St. (1861-71), 93 York Rd. 1871-90); Thomas Norris tool and planemaker 57 York St. (<1871-1899).

Same planemakers and tool dealers in London Ordnance Survey 1872.

The 1862 York St. renumbering and the sequence of address listings in the 1870 London Directory correspond, and there also is a mid-20th century account of the renumbering for York Street numbers as given in “Survey of London: Volume 23, Lambeth: South Bank and Vauxhall”, ed. Howard Roberts, Walter H Godfrey ( London, 1951).

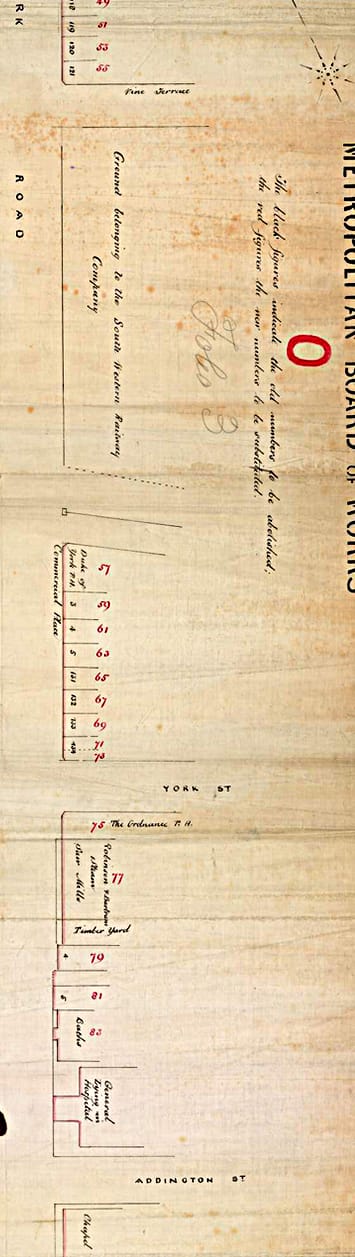

York St. Renumbering, east side, 1862. Lambeth City Archives.

Posthumous listing for Charles Badger “Tool Dealer,” at 93 York Road (J. Holland 1872-1890). From the London Post Office Directory for 1870.

Buck/Towell

Towell mitre plane, 245 Tottenham Court Road, marked and sold by Buck (1831-1861) This Towell mitre plane has an iron made by I.&H. Sorby, as do most Towell mitre planes.

A minority of Towell mitre planes can be found with Ward, and other makers’ irons, however. All of the irons would not have a nib; when the nib came into use by Spiers, Moon, and Cox in the late 1840s, Towell did not adopt it. Towell and his son, Robert Jr., would continue to make planes as late as 1863.

Buck (Towell) mitre plane, stamped 245 Tottenham Court Road., dating from the early 1830s and through the 1850s. By 1851, George Buck’s business had grown to the point where 8 men were employed there, as reported in the UK census. 245 Tottenham Ct. Rd.was George Buck’s address from 1838 to 1861. The “BUCK 245 TOTTENHAM Ct. Rd.” stamp used the same lettering font/format as the “Rt. TOWELL LONDON” stamps. It makes for a strong indication that Robert Towell himself applied these stamps in his workshop. For more information on Robert Towell, see the page on “Early English Mitre Planes, Part II” This plane is also very similar, if not identical to the one used to plane spotted metal for organ pipes at G. Fincham Organ Builders.

Dual marked plane: Buck on bridge and Towell on rear infill. Someone lost their patience with this tool, and filed the mouth open. Photo by Robert Leach. From website http://www.oldhandtools.co.uk/blog/english-mitre-planes.

10″ Towell mitre plane, with 2″ Ward iron; stamped on bridge, TOWELL LONDON, and on front infill, BUCK 245 Tottenham Court Road. Formerly Bob Funnel collection. Photo from D. Stanley Auctions, lot 266, September, 2014

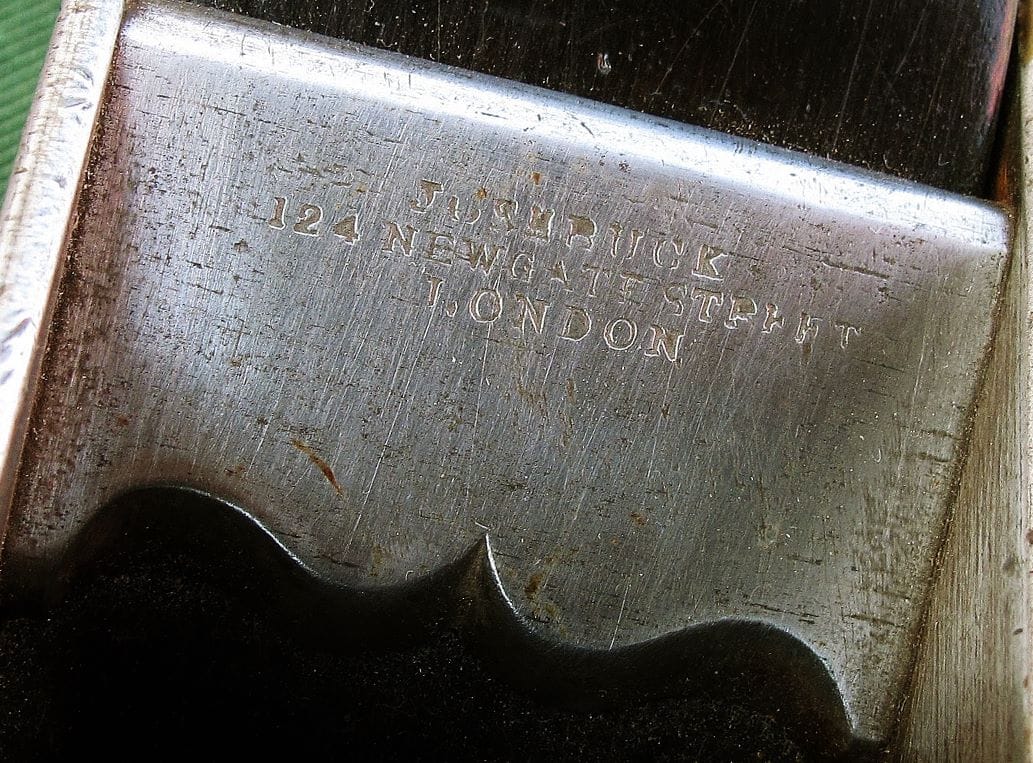

Mitre plane bridge made by Robert Towell, but marked Joseph Buck 124 Newgate St., London (also 91 Waterloo Rd.., Lambeth). Photo from Hans Brunner

Here is another mitre plane, 10″ long, with a 1 7/8″ Ward & Payne cutting iron, stamped Joseph Buck 124 Newgate St., London. With a Ward iron instead of I.& H. Sorby, and the placement of dovetails on either side of the mouth, rather than a tongue and groove joint, I am inclined to think this plane was made a little later, circa 1840s and 1850s.

Also, with a long iron, barely used. This example was found in New England (after decades of storage), and never in a dealer sale or auction, It was likely brought to America by an English immigrant in the mid-19th century.

Sole of J. Buck mitre plane, showing tight mouth. Dovetails were placed on either side of the mouth, instead of the usual tongue and groove joint. After almost 200 years, this has not posed a problem.

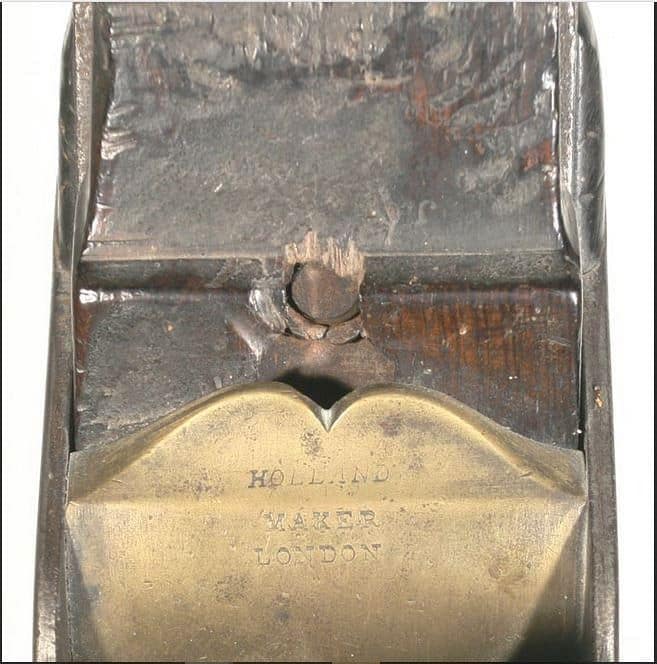

Buck/Holland

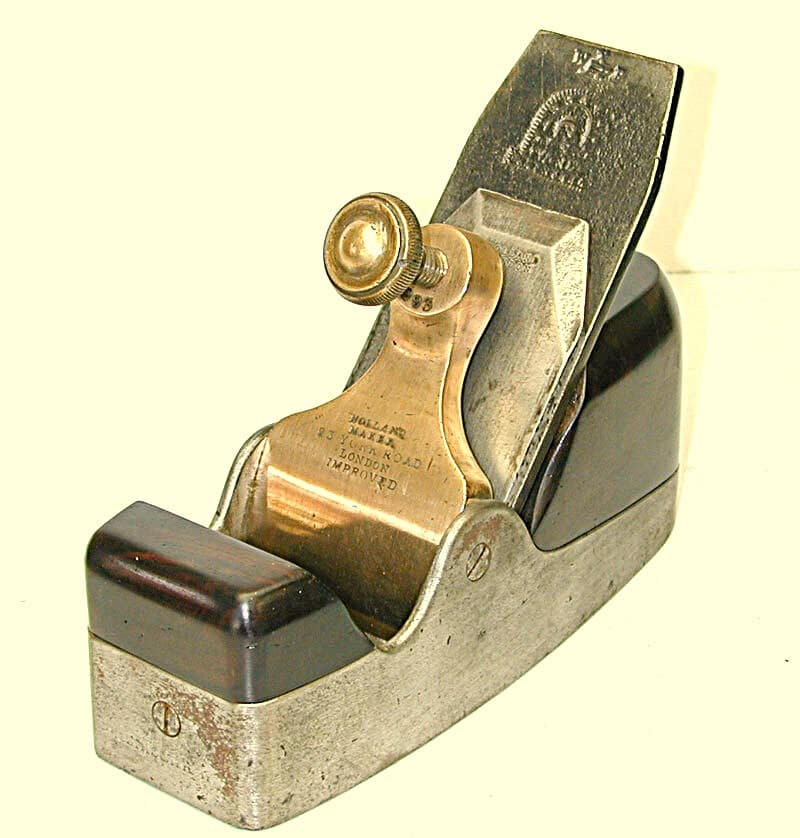

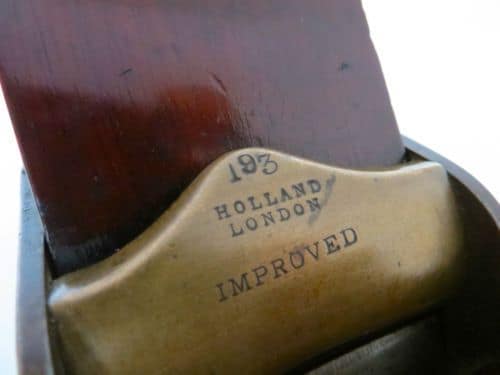

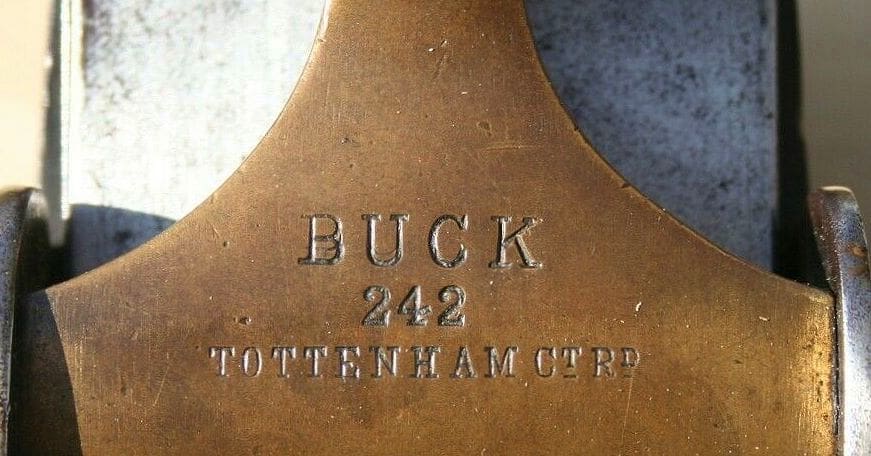

The following three Buck mitre planes share similar fundamental aspects as well as many details. Considering the similarities of these three Buck mitre planes, it’s apparent they were made by the same maker, and I believe that was John Holland (1830-1912). What makes these planes unique, is the convex, or arched bridge done in iron or steel, with a Cupid’s Bow, or Accolade at the leading edge. These planes are not found with a makers’ mark, but are found exclusively marked by Buck, at Tottenham Court Road.

Since the 1830s, both George and Joseph Buck had been buying in Towell mitre planes, which had been stamped with the Buck name and address. I believe that George Buck approached John Holland, and asked him to manufacture a traditional, old fashioned mitre plane, in the style of Robert Towell, with the then traditional and familiar Cupid’s Bow/Accolade.

Making a special order, or unique plane for a product that was to be purchased, or bought-in, wholesale to the trade, was highly unusual, but not unprecedented. Much earlier, in the 1850s and early ’60s, Mathieson sold a limited run of Improved Mitre Planes, with a unique rounded infill, while the metalwork was virtually identical to that of the Spiers Improved Mitre Planes of that period.

Holland mitre plane (attributed), 245 Tottenham Court Road, 9 3/8″ long, and marked by Buck; sole of Buck 245 mitre plane with small mouth.

This is an earlier example of a Holland/Buck mitre plane, 245 Tottenham Court Road, probably circa 1857-66; the address was actually 245-247 Tottenham Court Road from 1862 to 1866. In around 1857, John Holland moved to Lambeth along with his family. The stamp is otherwise the same as the other later Buck mitres (247 and 242), shown down the page, with similar features, including the convex bridge. The bridge is less convex than the later mitres, but it is still noticeable.

Holland/Buck 245 mitre plane heel, with nibbed 2″ Ward & Payne iron. Almost invariably, these Buck/Holland mitre planes have snecked, or nibbed Ward & Payne irons. The earlier Towell mitre planes, in original condition, typically have I. Sorby irons, with no nib.

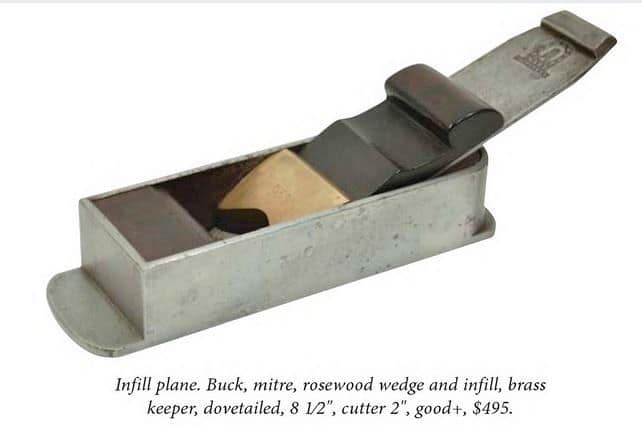

Holland/Buck mitre plane, 8 1/2 long, with 2″ nibbed Ward & Payne iron (mark reg.’d 1844). 247 Tottenham Court Road (1867-1879). Layout and construction of this Holland/Buck 247 mitre plane was essentially similar to other examples; the plane body was made shorter by decreasing the length of the toe in front of the mouth, as well as a shorter front infill. The width of the plane is full, and comparable to the other two Buck/Holland examples: 245 and 242 Tottenham Court Road, respectively.

Holland mitre plane, 242 Tottenham Court Road, marked and sold by Buck, (1880-1890). 10 1/4″ long with 2″ Ward & Payne nibbed iron; convex bridge, with Cupid’s bow. It’s unusual to see many box mitre planes made after 1860, and more so to see one with a cupid’s bow bridge after the 1870s.

Convex bridge from Buck/Holland mitre plane, showing address of 247 Tottenham Court Road, circa 1867 to 1879. Note the same stamp format as well as an identical cupid’s bow to the two mitres shown here. Photo from internet source.

The Norris no. 11 bridge has similarities with the Buck mitres in question. Because of these similarities, Thomas Norris cannot be ruled out. In any case, there was a significant gap in time between production of the last Buck/Holland type mitres in the 1880s, and the introduction of the Norris no. 11 small box mitre circa 1914-1925. Only a few of these were made.

Considering that Buck bought in planes from Towell, Spiers, Slater, Holland, Miller, and Norris, which of these makers can be eliminated as the possible maker? Since the three Buck planes with a convex cupid’s bow bridge shown on this page were dovetailed, only Spiers, Holland, and Norris dovetailed their mitre planes. Towell dovetailed his planes as well, but his productive years (1810-1863 at the very latest) were too early for consideration here. These planes were made ~ 1860s to 1890. Miller did not make any mitre planes, and his planes were all cast in gunmetal. Slater made a modest number of cast iron mitre planes, appearing mostly unmarked, or rebadged, such as for Tyzack or Moseley.

Three Buck Mitre planes with convex bridges.

245 Tottenham Court Road circa 1950.

245, 247, 242 Tottenham Court Road as depicted in Tallis’ “Street Views of London,” 1838-1840.

George Buck’s Tool Warehouse, 242 Tottenham Court Road, circa 1890. Left window: “Pianoforte Makers; Carpenters; Coach Makers & Engineer’s Tools.”

Buck/Spiers

Buck sold rebadged Spiers planes, and four examples can be seen below. They do not appear to be different from Spiers signed planes in any way. This is to be expected, as it would be unlikely for a plane maker to sell their planes at a lower price, wholesale to the trade, with any special new designs or modifications unless required by the dealer. Early Spiers mitre plane marked “Buck 245 Tottenham Court Road.” Stewart Spiers sold many early planes to Buck, Moseley, Mathiesen, and Archer, as well as other dealers. Planes were either rebadged by the tool dealers, or by Spiers himself. Some early Spiers examples were never stamped with a mark at all.

Buck/Spiers mitre plane, 245 Tottenham Court Road, circa 1855-1865.

This Spiers 8 1/2 inch mitre plane sold in the Martin Donnelly November 2020 Antique Tool Auction for $2,400. It looked to be in fine condition, with the only apparent issue being the bounce of the name stamp on the lever cap. Photo from MJD Tools, November, 2020.

A similar 8″ Spiers mitre plane to the example above, also the 1850s Spiers price list: with early style front infill, early lever cap screw, squared-off flanges, double bend in sidewalls at heel, rear flange (not exclusively a later feature for 8″ examples), side screws for attaching lever cap, and a relatively short neck on lever cap. Photo from Spiers.planes.com

Buck (Spiers) mitre plane, c. 1870s. Standard Spiers design. Warman’s Price Guide, Clarence Blanchard, 2011.

Buck/Spiers mitre,1870s. Photo by Bill Carter.

Buck (Spiers) panel plane lever cap, 247 Tottenham Court Road, circa 1867-1879. This was among the later Spiers/Buck planes to be bought in and rebadged by a dealer. A few later examples can be found, having lever cap screws without cusps, but they are scarce. Mathieson bought in planes by Spiers until c. 1898.

Buck/Holland (continued)

Holland would be the remaining possible maker of these dovetailed mitre planes, other than Norris, and there’s a shortfall of Holland’s examples available for comparison. What makes the Holland/Buck type mitre planes unusual, is that they seem to be limited to the Buck dealer stamp, and do not appear elsewhere with the original planemaker’s stamp. Of course a maker-stamped mitre might show in the future, and if it does, it could give a more definitive answer as to who made all the Buck mitres with cupid’s bow and curved steel bridges, from the 1860s and into the 1880s. While these Buck mitres are rare, a fair number of this vintage and type have shown up over the years: there are more Holland/Buck mitre planes with the convex steel bridge than Holland-marked mitre planes with a gunmetal bridge. Enough Holland/Buck mitre planes were made that fitting numbers were necessary to keep all of the parts organized in the workshop.

In recent years, antique tool dealers and auctioneers have proffered their own assessment as to the identity of the maker of these mitre planes. Two tool dealers and one auctioneer advanced Norris as the likely maker, and one auctioneer proposed Holland. A rebadged Norris plane has a greater potential to achieve higher prices, so this evaluation may not be entirely objective.

A key differentiation between the Holland/Buck type mitre plane and the Norris No. 10 mitre plane is in their construction, which is hard to see in the Norris mitres because the sides and sole were both made of steel. In most of the Norris No. 10 mitre planes, there are 3 dovetails on each side: 1 dovetail in front of the mouth, and 2 dovetails behind the mouth (exceptions exist). In the Holland/Buck type mitre planes, there are 5 dovetails on each side: 2 dovetails in front of the mouth, and 3 dovetails behind the mouth. I have observed this 2-3 construction on 3 Holland/Buck type mitre planes in my collection, and the 1-2 construction on 5 Norris No. 10 mitre planes, also in my collection. In a definitive Holland mitre plane (formerly Max Ott collection) there are 5 dovetails on each side: 2 in front of the mouth, and 3 behind. Additionally, I have seen these same construction fundamentals in other similar mitre plane examples.

Bill Carter, a famous U.K. planemaker, who makes small mitre planes as a specialty, studied the historical English and Scottish planemakers in order to inform his own work as well as to satisfy his natural curiosity. From the beginning of his planemaking in the 1980s, Bill Carter made detailed drawings of antique planes, showing dimensions, bed angle, mouth construction, thicknesses, and dovetailing. In recent years, Bill Carter has made videos showing his work methods, including this one, where he revealed his archive of drawings of antique mitre planes. At 5:40, Bill Carter stated that he had observed a number of Norris mitre planes with 1 dovetail in front of the mouth, and 2 dovetails in back of the mouth.

Working years for Holland ranged from 1857 to 1891 (with few planes marked with later addresses) which encompassed the time in the 1860s when the earlier plane was made. While Norris advertised that he was established in 1860, it was realistically more as a maker of wood planes and other joiners’ tools early on. Thomas Norris (1836-1906), described his profession in the 1861 UK census as a non-specific “Joiners’ tool maker,” then in the 1871 UK census as a “Tool maker;” and next in the 1881 UK census as a “Plane tool maker.” Finally, in 1890, Thomas J. Norris listed his specialty as an “Iron Plane Maker,” in the London City Directory. This does not mean that Thomas Norris did not make metal planes before 1890; it did suggest that before 1890, metal planes were not necessarily a primary focus for Thomas Norris.

Some Holland History

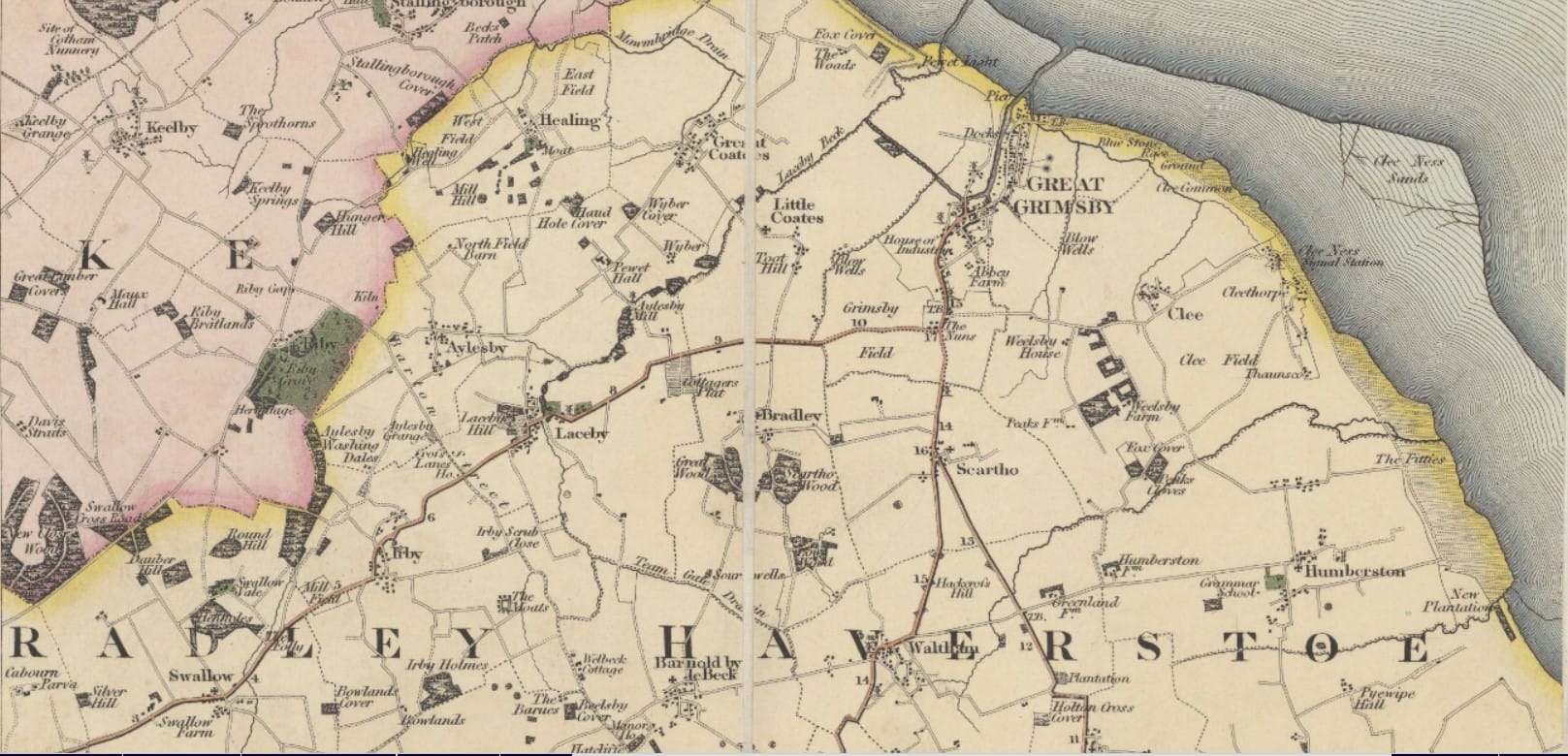

John Holland was born in Riby, Brocklesby Lincoln, which is near the South shore of the Humber estuary on the East coast. His parents were John Holland Sr. and Mary Mallender, and he was baptized on 4 July 1830, in Riby. Today, Riby is a tiny hamlet of 129 inhabitants.

Riby Lincolnshire, from C. Greenwood 1830 map.

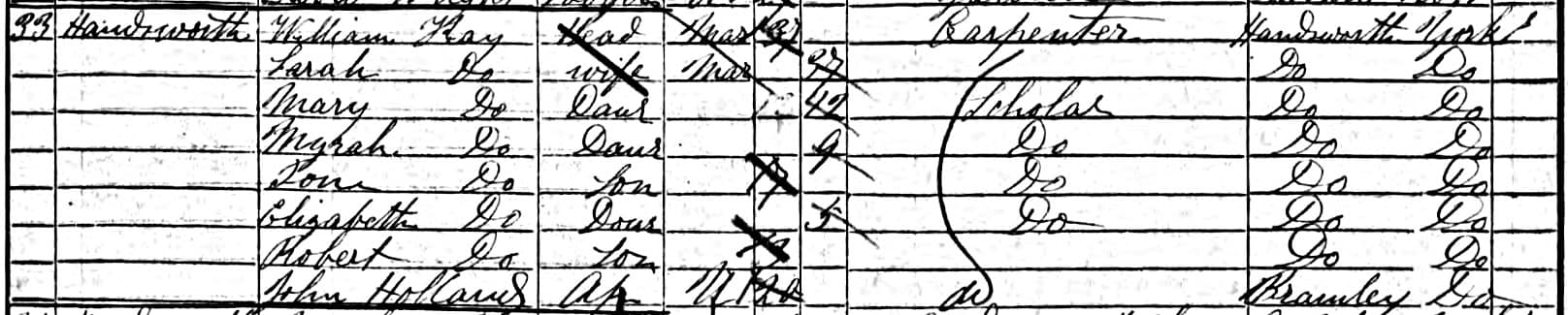

In 1841, 10 year old John Holland lived with his family in Bramley, in the northwestern section of Leeds. 1841 U.K. Census.

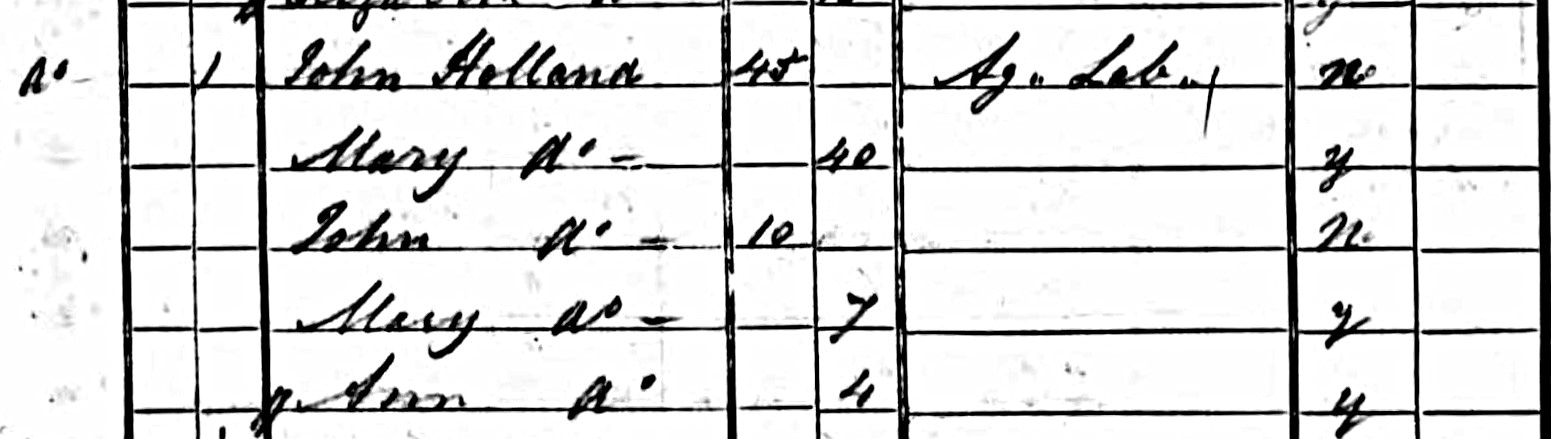

John Holland served an apprenticeship with William Kay, a carpenter who lived at 33 Handsworth, Sheffield, Yorkshire. 1851 U.K. Census. Bramley was incorrectly reported as place of birth, although John Jr. and his family were living in Bramley during the 1841 U.K. Census. John Holland Sr. was an agricultural laborer, and may have needed to relocate as necessary in order to be present where work was available.

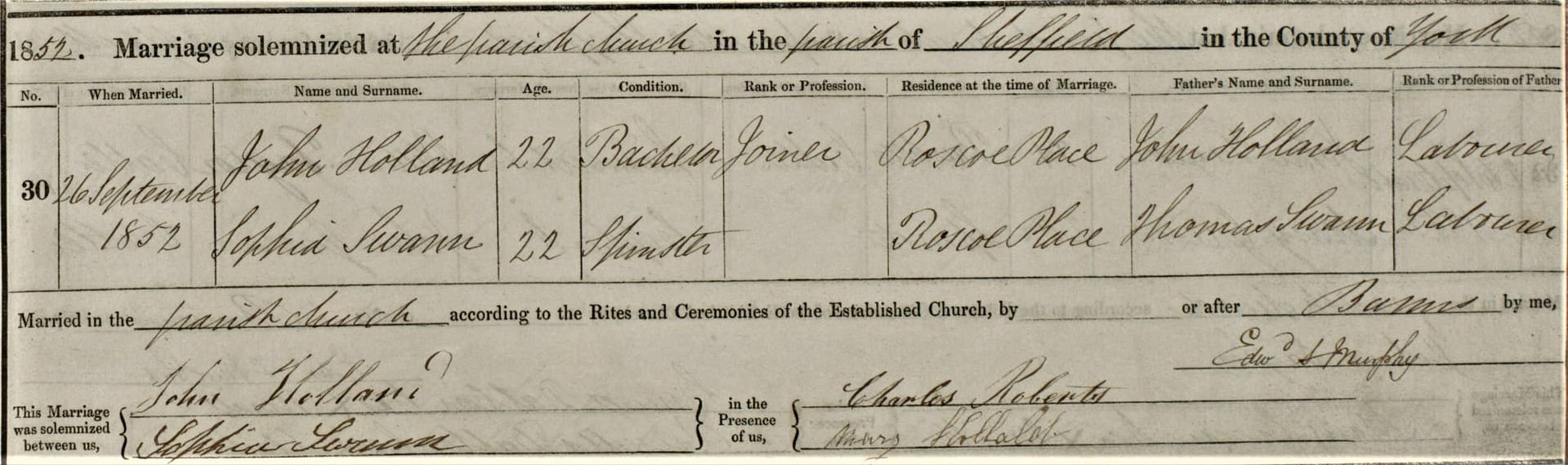

John Holland married Sophia Swann at the Cathedral of St. Peter & Paul, in Sheffield, on 26 September, 1852.

Sophia Swann (1830-1915) was born in the hamlet of Dalham, Suffolk County. Sophia met John while she was as a housekeeper working for John and Maranne Wick, a young couple in their late 20s, both chemists, living at 59 High St. in Sheffield. In his 1851 U.K. Census entry, Thomas Swann reported his trade as a “Butcher.”

John Holland Sr. age 52, born in Morton Lincolnshire. Also Mary Mallender Holland, 48; Mary, 16; Ann, 14. Was he a “Caster” or a “Carter?” 1851 U.K. Census.

John Holland Sr. listed his job as a “Caster” in his 1851 U.K. Census entry, and if this was true, may have exposed John Jr. to the metalwork and toolmaking that was so ubiquitous in Sheffield during the mid 19th century. There is a possibility, however, that the entry meant “Carter,” which would have been a wagon driver making deliveries–which was more in line with John Sr.’s work history of a “labourer.” Here is his 1851 U.K. Census entry so you can decide for yourself.

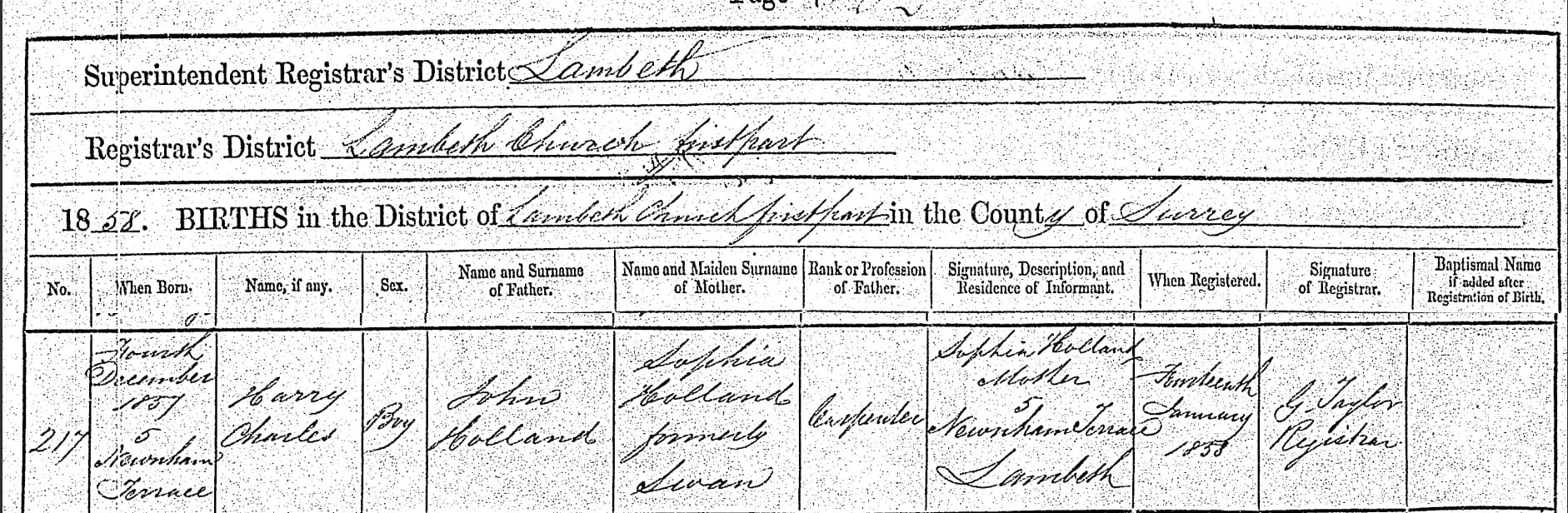

Harry Charles Holland was born 4 December, 1857, and the Holland family was living at 5 Newnham Terrace, in Lambeth, 2 blocks south of 68 Oakley St.

Newnham Terrace renumbering plan, c. 1893.

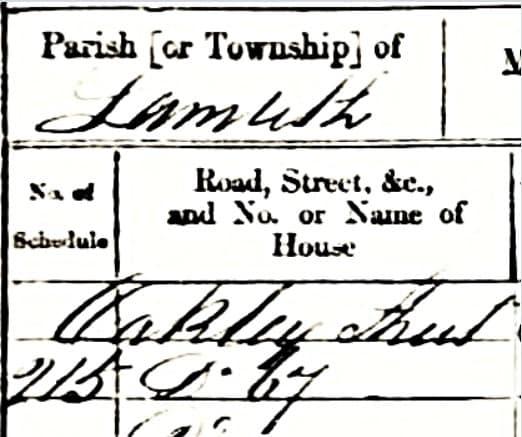

Oakley St. renumbering plan, 2 March, 1877. John Holland’s 68 Oakley St. address (<1860-1869) is marked on this map excerpt. –Old numbers in black, new (1877) numbers in red. Gibson St. crossed out and replaced with Oakley St.

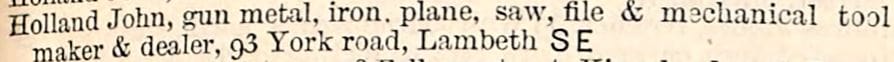

John Holland, “Tool Maker,” in Kelly’s l861 London Post Office Directory. Holland wasted no time establishing his tool making business; he probably started tool making work in 1857, when he moved to Lambeth.

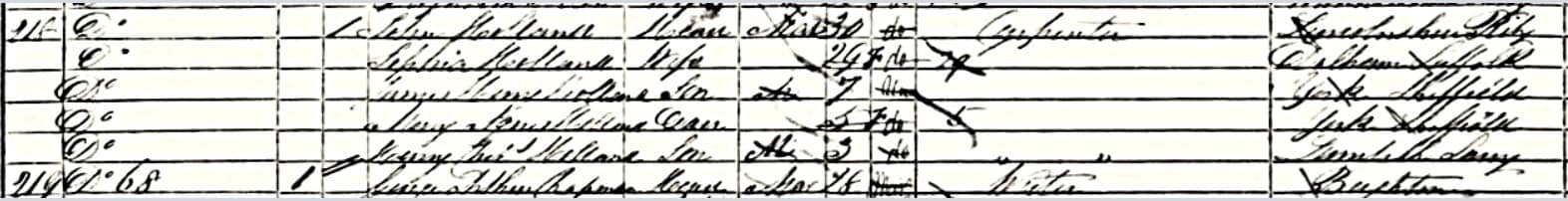

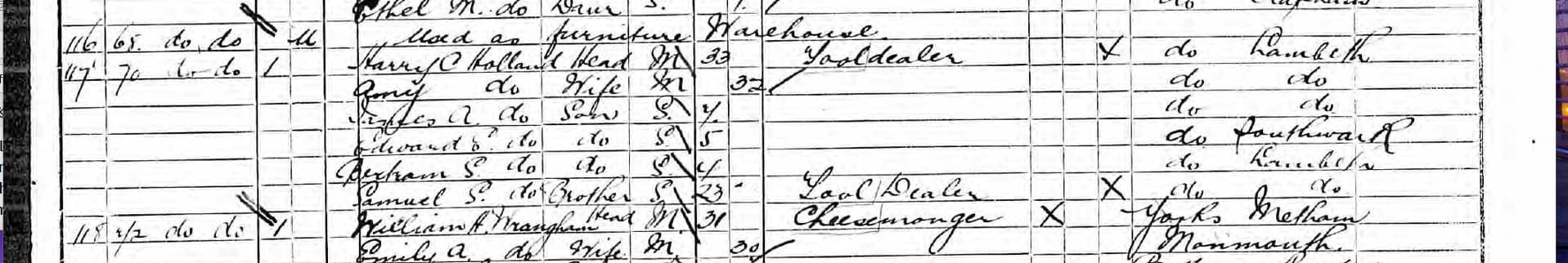

Detail of “Oakley Street,” in the 1861 U.K. Census

John Holland and his family at 67-68 Oakley St., in the 1861 U.K. Census. In 1861, the Hollands were one of four families living at No. 67 Oakley St., but there was only one family living at No. 68. No. 67 may have been a larger building, or the residents there may have been crammed in! At some point during John Holland’s stay at Oakley St., he purchased the properties at Nos. 68 and 69 Oakley St., which probably were cheap because it was not a prime neighborhood in Lambeth. After moving to 93 York Road, Holland rented out Nos. 68 and 69 Oakley St.

Holland’s description of his business underscored his initial involvement in iron and gunmetal planemaking. Searching for an apprentice 1864, John Holland posted the following ad in the Clerkenwell News: March 23, 1864. “Apprentice wanted to the Gun Metal, Iron Plane and Mechanical Tool Manufacturing; a premium required, Apply to Mr. J. Holland at 68 Oakley Street, Lambeth.”

Holland Smooth plane, No. 213. 68 Oakley St., London.

Holland 213 smooth plane interior.

Christopher Gabriel (1746-1809) assigned serial numbers to his mitre planes, and likewise, John Holland gave serial numbers to his smoothing planes. Holland’s numbers ranged from 14 to 1089 (subject to revision). Sometimes Holland would include his street address, and when he did, it can be observed that his lower serial numbers would show 68 Oakley St., and his later, higher serial numbered planes would show 93 York Rd., as would be expected.

Many of Holland’s other planes did not have numbers, for example, his mitre planes lacked them; with so few marked Holland mitres, they were probably considered unnecessary. Also, Holland left many of his planes unmarked, in order to be bought in by tool retailers and stamped with their own proprietary inscription. These planes would have been without numbers as well. Sometimes the initials “J.H.” would be stamped in a less prominent location, such as on the bed, or on the iron.

In the case of Smoother No. 213, a large “I.H.” was added into the casting underneath the rear infill. I would not have discovered this unless the rear infill had come unglued. Additionally, “Holland, London” was stamped into the underside of the bronze lever cap.

John Holland, 68 Oakley St., in The London Gazette, on 6 November, 1866. Gunmetal and iron, separate commodities. In 1869, John Holland was listed in Kelly’s, Post Office and Harrod & Co., Trade Directory as a “Gun[metal] and Iron Plane Maker,”

John Holland, entry in the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1867.

John Holland, listed in the London P.O. Directory for 1870, under “Metal Merchants.” Early on, John Holland concentrated on metal tools, and was even listed as a dealer in gunmetal stock in 1870.

John Holland, in the 1870 London Post Office Directory. 1870 London P.O. Directory: “John Holland, Gunmetal & Iron Planemaker. 68 Oakley Street, Lambeth. S.E.”

Oakley Street Scene from circa 1925, with Old Victoria Theatre in background. 68 Oakley St. would have looked like the three story plain facades in the right foreground. Photo from facebook.

Holland smoother 93 York Road. Photo by Ar. Clarence.

Since John Holland took over established metal planemaker, Charles Badger’s workshop and tools at 93 York Rd. Lambeth in 1870, he would have been thoroughly prepared to produce infill planes during this early time period. By the time of the 1881 UK census, John Holland employed two men besides himself for his tool making enterprise.

Holland Chariot Plane. Photo from Old School Tools UK.

Holland Chariot Plane.

Holland Chariot Plane with lugs instead of bridge, showing influence of Badger. Photo from Ar. Clarence, Pinterest.

Holland mitre plane, as sold in Bearne Auctions, U.K. 2022.

Holland mitre plane, formerly from the Max Ott collection. Stamped “J. HOLLAND” on underside of bridge. 2 dovetails in front of the mouth; 3 dovetails behind. Nibbed Ward iron.

A definitive Norris no. 10 mitre plane with a curved gunmetal bridge with cupid’s bow in back is shown rebadged as a Buck at the bottom of this page. There are no differences between the Buck and a Norris no. 10 other than the stamp on the bridge.

Below you can see the curved bridges of both Norris and Holland. The influence of Holland on Norris is obvious. And that applies to the three previous Buck mitre planes as well.

Norris gunmetal bridge from a no.10 mitre plane. Mitre and smoothing planes with this bridge can be found marked BUCK also. Photo from Jim Bode.

Holland bridge on smooth plane. Photo from Ar.clarence, pinterest.

Holland mitre plane-Mar. 2015 Brown auction.

Later Buck stamp, found on rebadged Norris smoother and panel planes. Photo from Ebay U.K

Holland bridge. Norris’ bridge is quite similar. Photo by Lee Richmond.

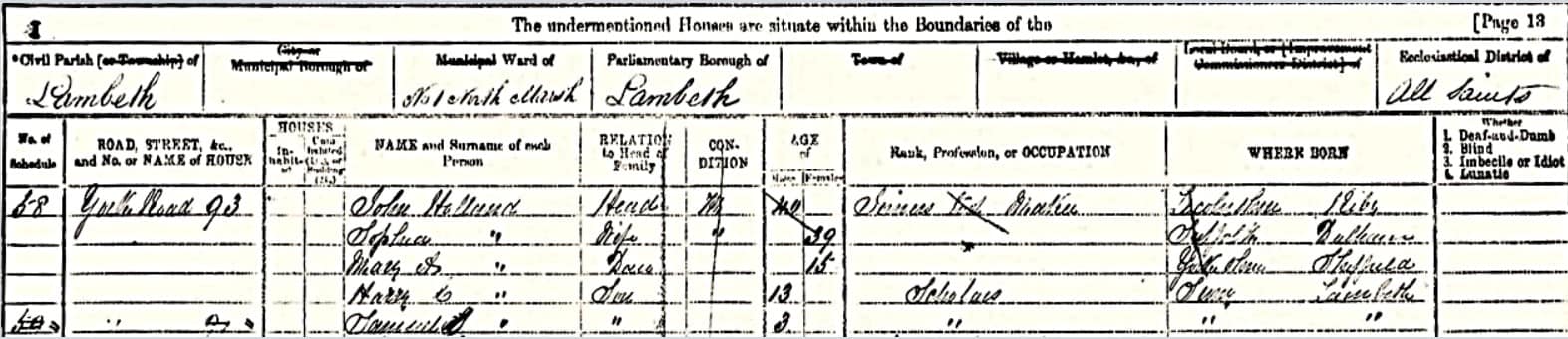

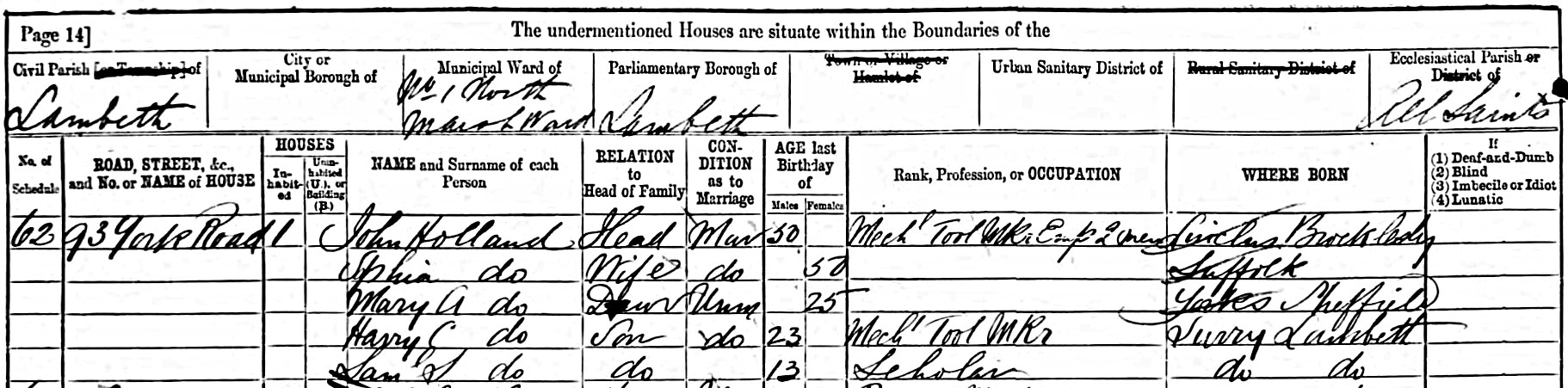

John Holland and his family at 93 York Road, in the 1871 U.K. Census. 93 York Road was the former workshop and living quarters of Charles and Isabella Badger. Charles Badger died 28 September, 1869.

York Road scene, taxi stand, circa 1890s.

John Holland moved to 93 York Road. 1872 London Post Office Directory.

York Road, Southeast side, c. 1950, showing 93 York Road, John Holland’s old address, 1871-1890, just to the left of the York Restaurant (King Brothers storefront).

John Holland, in the 1880 London Post Office Directory. “Gunmetal, iron, plane, saw, file. & mechanical tool maker & dealer:” Holland was making a wide range of products. Not just planes.

John Holland, “Mechanical Tool Maker, Employs Two Men” in the 1881 U. K. census. Many Holland planes were bought in by tool dealers such as George Buck, many were stamped “J. Holland,” and many were sold unmarked. Holland was a prolific maker, and having a crew of two men–and an apprentice or two–made this possible.

John Holland was involved in two newsworthy incidents during his career: South London Press, 28 April, 1883.

South London Press, 28 April, 1883, part 2.

Here is John Holland’s second newsworthy event, published in the Clerkenwell News, 24 April, 1885:

Yesterday shortly before ten a loud explosion was heard in the neighbourhood of Westminster Bridge Road causing considerable alarm. The police ascertained that a serious explosion had occurred at the tool and cutlery establishment of Mr. Holland at 93, York Road. It appeared that at the time the son of the proprietor Samuel Holland aged 17, upon entering the parlour at the rear of the shop had smelt strong of gas. Unfortunately he sought the cause with a naked light, shattering the windows in the shop and damaging the display trade, which fortunately will not prevent the business from being carried on as usual.

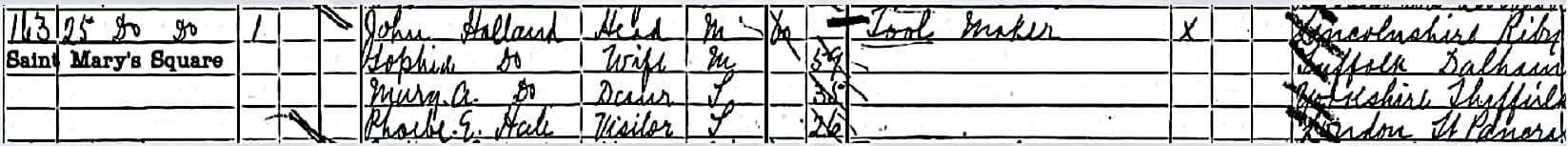

John Holland, “Toolmaker,” and his family, living at 25 Saint Mary’s Square, Lambeth, during the 1891 U.K. Census. By the 1891 U.K. census, John Holland was living at 25 St. Mary’s Square in Lambeth, while the P.O. directories listed Holland at 26 Richmond, St. George Road through 1893. After John Holland left 93 York Rd., his apparent output of tools diminished, or stopped completely at some later point.

John Holland, 26 Richmond St. St. George’s road S E, in the 1890 London Post office Directory.

John Holland, “Tool Manufacturer,” in the 1895 London Post Office Directory.

John Holland moved to 30 Garden Row sometime before the fall of 1894, and stayed there until at least 1907.

Harry Charles became involved with running a retail tool and cutlery business from 25 Falcon Road, Battersea until his death in 1924, and for a time, Harry opened a second store as well. Samuel Swann started out in 1891 as a Tool Dealer along with Harry at 70 Falcon Road, but he soon transitioned into working as a carpenter and joiner.

John and sister Mary Holland, 30 Garden Row, in the 1901 U.K. census. During the 1901 census, John Holland, 70, declared his job as a “Carpenter and Joiner,” and was living at 30 Garden Row, in Southwark along with his younger sister Mary, 66. John was listed in the London P.O. Directory for 1902 as a “Tool Manufacturer.”

John Holland, “Tool Manufacturer,” 30 Garden Row, London P.O. Directory, 1902.

John Holland, in the 1907 London Commercial Directory.

1907 was John Holland’s final year for a business listing at 30 Garden Row, Lambeth.

In 1901, John Holland and Sophia Swann Holland were no longer living together; Sophia moved to 335 Battersea Park Road to live with her daughter, Mary A. Holland, who was working at a Coffee House Keeper. Sophia, aged 66, was working in a grocery store. Most likely, Mary and Sophia chose to live in Battersea because Harry Charles was located in Battersea, working as a tool dealer from 25 Falcon Road. By this time Samuel Swann Holland was working as a “Carpenter and Joiner,” and living with his wife and young son at 96 Amelia St. in Southwark.

Falcon Road, Battersea, at the turn of the 20th century. John Holland’s 30 Garden Row address in Southwark was three miles away from Falcon Rd., and 1 mile from 96 Amelia St., where John’s youngest son, Samuel lived in 1901. Ten years later, Mary and Sophia were still in Battersea, living at 51 Eland Road, Lavender Hill, and Mary was working as a “Carver” in a restaurant.

John Holland, 80, was listed as a retired “carpenter,” in the Tooting Bec Asylum, Wandsworth, during the 1911 U.K. census; senility must have overcome him by around 1907.

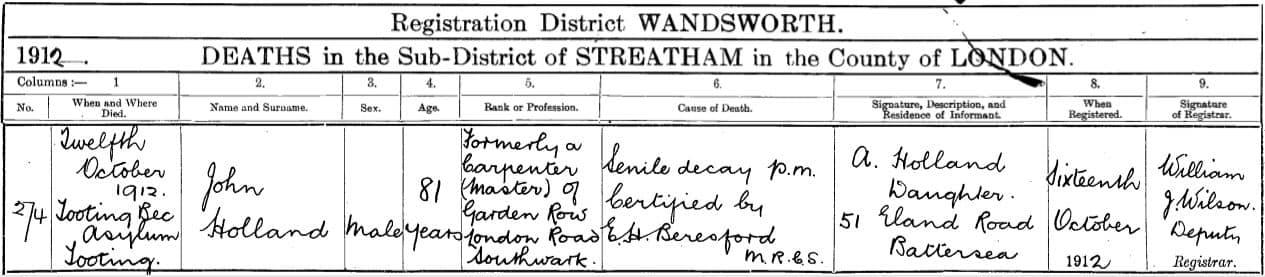

John Holland’s death certificate. John Holland passed away in Wandsworth on 12 October, 1912. 81 (actually 82) was truly an advanced age for the time. John Holland was one of the most long lived planemakers compared to all his peers.

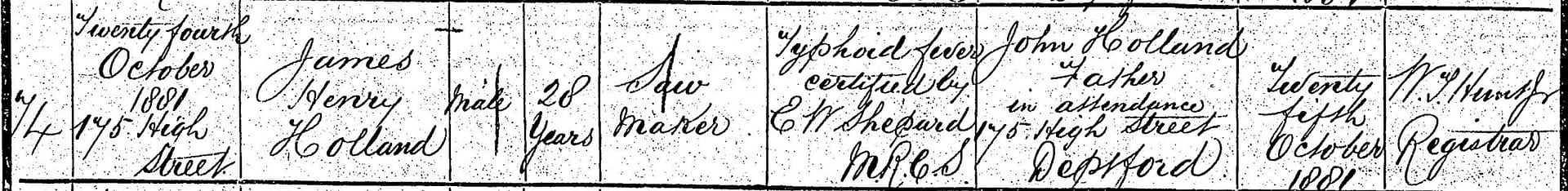

ohn and Sophia Holland were reunited in death. This part of Ladywell and Brockley cemetery has been overtaken by trees. Photo by Steve Johnson, 2020. John Holland was interred with his eldest son James Henry, who died 24 October, 1881 at the age of 28, leaving a wife and two young children. James Henry was also a tool dealer. John, James, and Sophia, who died in 1915, were all buried at the Ladywell and Brockley cemetery, in Lewisham, an outer borough Southeast of London.

Some Norris Family History

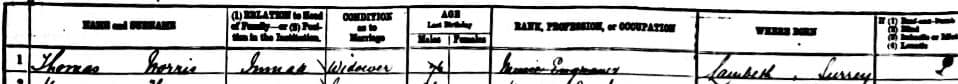

Thomas Norris I (the elder) was baptized 30 December, 1804, at St. Mary’s Church in Lambeth. Thomas’ parents were George Norris (1773-1845), and Rebecca Cooper, (1775-1843). George and Rebecca were married in 1802.

Thomas Norris married Jane Taylor at St. Savior Church in Southwark, 3 July, 1827. Thomas (1804-1886) and Jane (1803-1871) had the following children: Jane (1831-1878), Thomas James II (1835-1906), Edmund (1837-1928), Sarah, (1840-1910), Rebecca, born 1842, Harriet Mary, (1847-1919), and Warnell, born 1847.

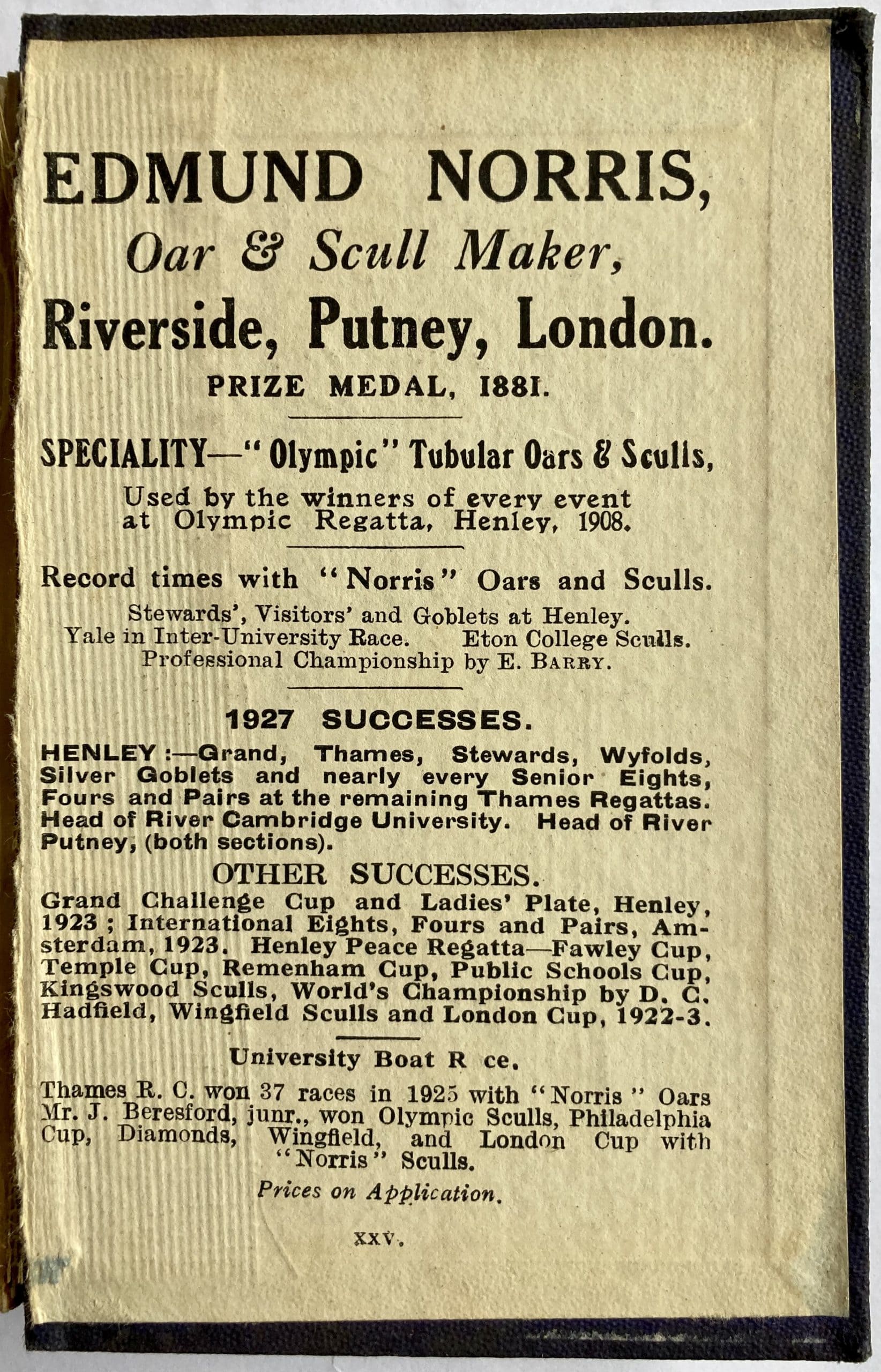

Edmund Norris advertisement, c. 1928.

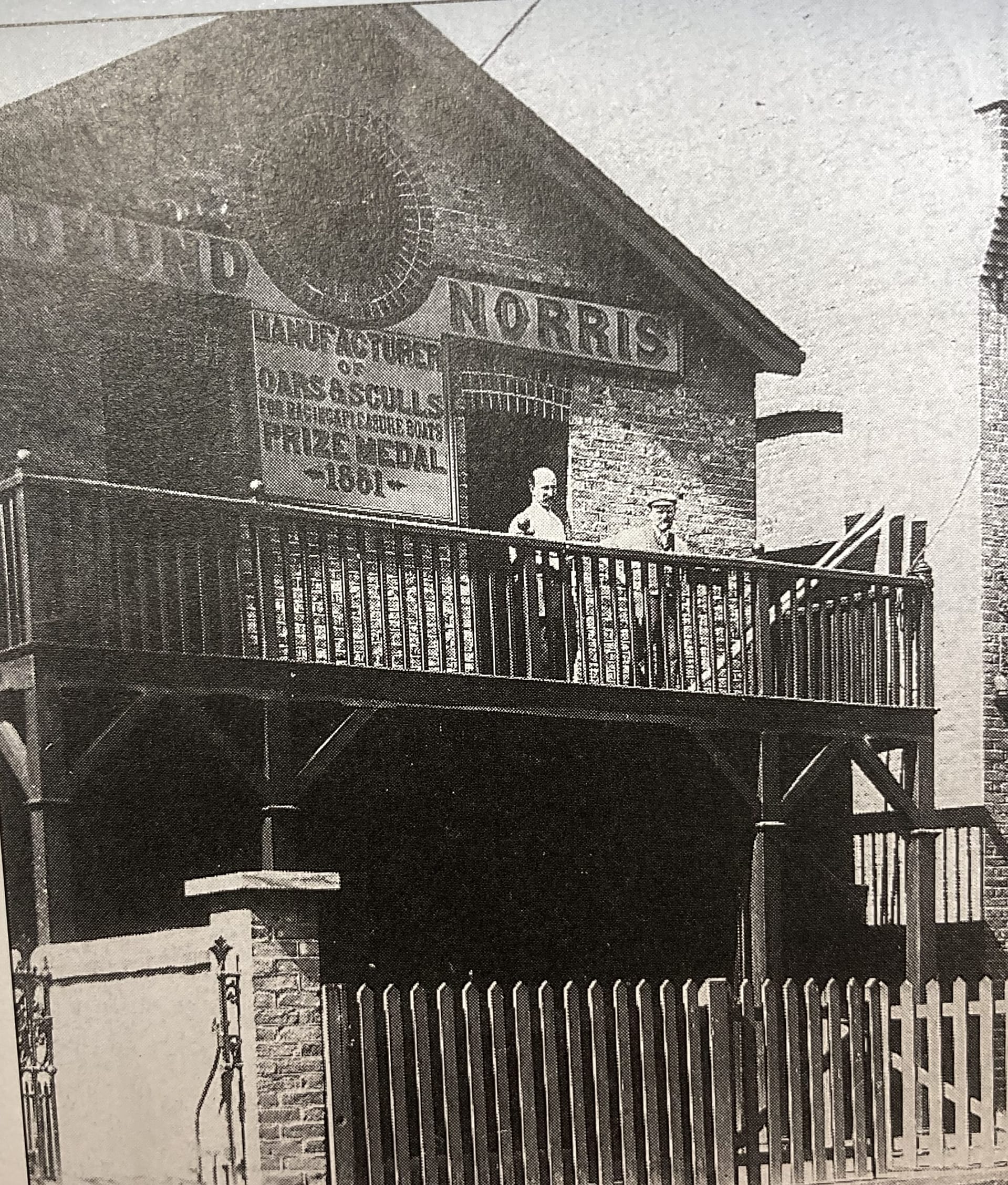

Edmund Norris’ Boathouse/Workshop on the Putney Embankment. Photo c. 1907. From Heartheboatsing.com

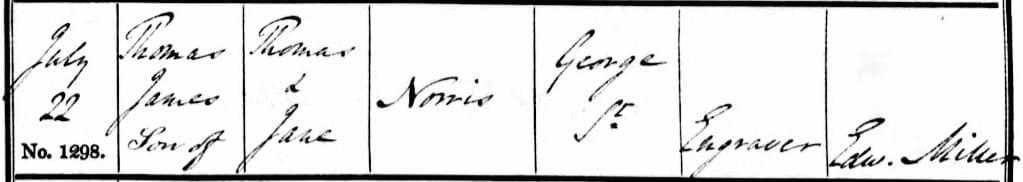

Thomas Norris Sr.’s baptism, 22 July, 1835, at St. Mary’s in Lambeth. Thomas James I was a music engraver on George St. in Lambeth.

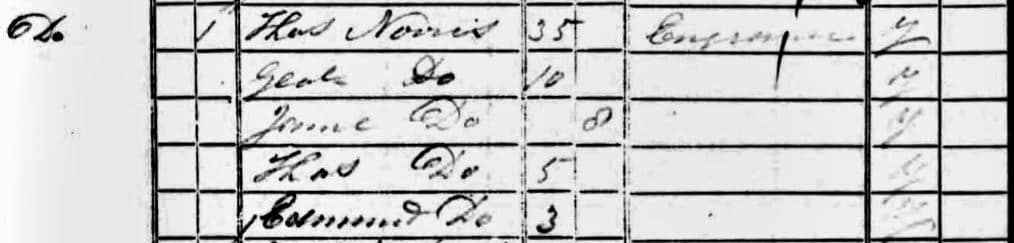

Thomas Norris I on George St., Lambeth, in the 1841 U.K. census.

Thomas Norris I on George St., Lambeth, in the 1841 U.K. census.

Thomas II and Jane Norris, at 18 Northings Head Yard, Lambeth, in the 1851 U.K. census. Thomas II, 16, was listed as an “errand boy” in the 1851 U.K. census.

Thomas James Norris II married Eliza Knott, on 15 May. 1859, at St. Mary’s Church, Lambeth. Thomas married Eliza Knott (1839-1918), and surviving children (from as many as 7) included: Thomas James (1860-1936); Ada Jane, (1862-1944); Clarence (1867-1876), Elizabeth (1870-1949); Edith A.(1874-1959). In 1859, Thomas Norris declared his profession as a “tool maker.”

Thomas Norris I., and Jane, with Jane Knott, born 1857, 25 King’s Head Yard, Lambeth. 1861 U.K. census.

Thomas Norris I’s 1873 admission to Lambeth Workhouse. Thomas Norris I (1804-1886) was a “music engraver,” which was a skill that involved a great deal of precision. By the 1870s and 1880s, Norris the elder was admitted several times to the workhouse.

Thomas Norris I, “Music Engraver,” in the Lambeth Workhouse, U.K. census, 1881.

Thomas Norris I (right person, wrong job), age 80, died of bronchitis on 8 March, 1886, in the Lambeth Workhouse.

Thomas J. Norris III was born 27 June, 1860, and was baptized 22 July, 1866 at St. John the Evangelist, Lambeth. Thomas Norris III (1860-1936) was the oldest son: first the apprentice, then partner and successor to his father in the business of making tools. Both father and son were baptized on 22 July.

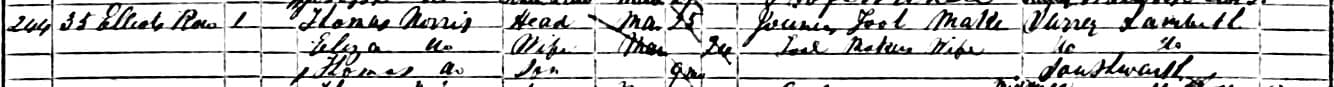

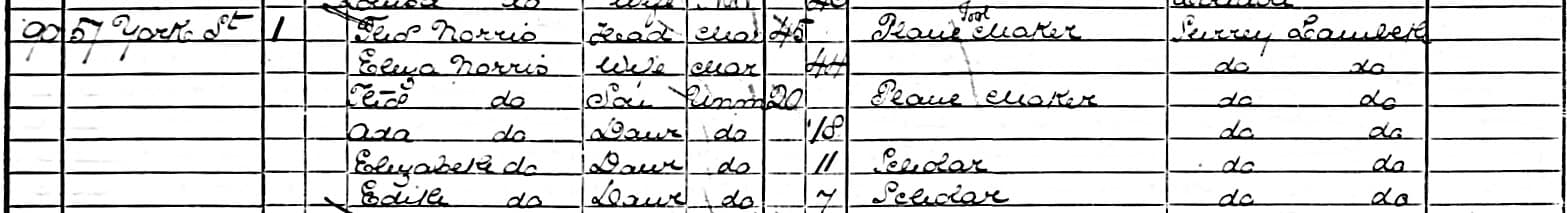

Norris, 1861 U.K. census, 35 Elliotts Row, Lambeth. Early census and city directory information for Norris indicate that he produced joiner’s tools of a general nature, rather than specializing in planes.

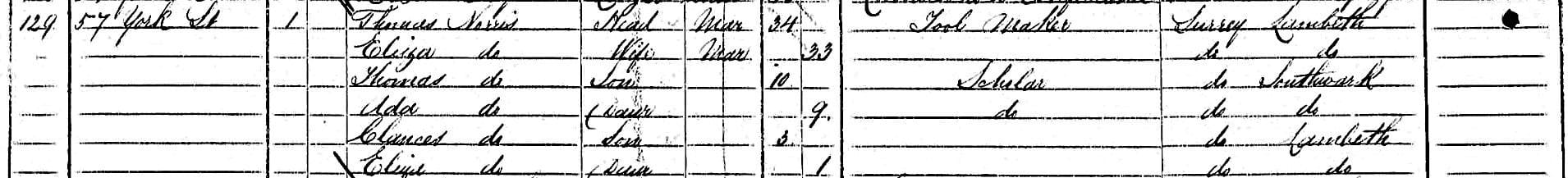

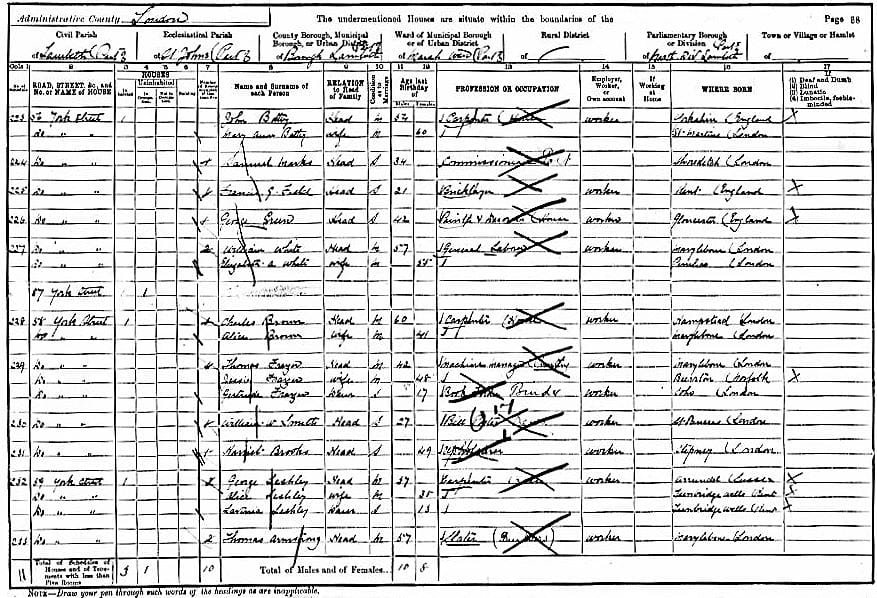

Norris, 1871 U.K. census, 57 York St., Lambeth.

Thomas Norris II’s 1868 listing in the London Post Office Directory. Thomas J. Norris II’s early success as a plane and toolmaker was due, in major part, to his business relationships with Joseph and George Buck. Many early Norris planes were bought in by Buck and rebadged “BUCK.” This connection between Buck and Norris, was far from exclusive, however. A Buck infill plane with what appears to be Norris-like features may actually not be made by Norris. John Holland had an established business relationship with Buck as well, and Holland had a major influence on Norris’ planemaking. The same could be said of Stewart Spiers. Mitre planes shown here serve as an example of Holland’s stylistic influence on Norris. Norris did establish a tool making business circa 1860, so it turns out that later Norris advertising was not an exaggeration.

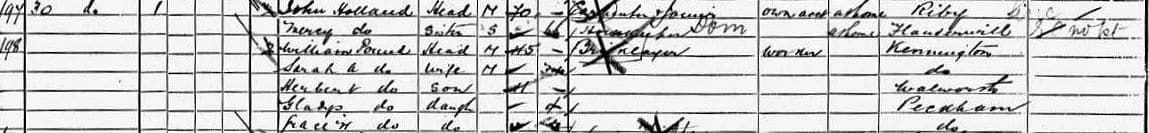

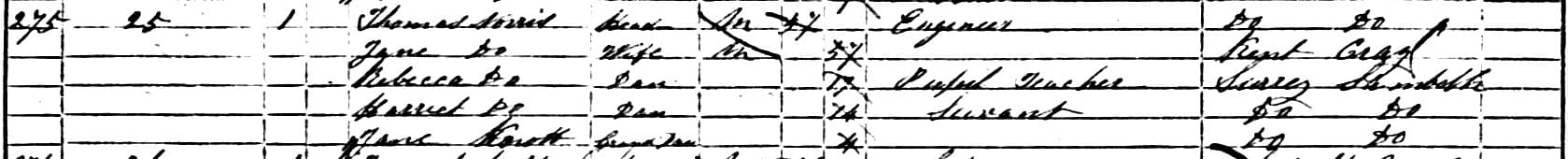

Thomas J.Norris Sr. and Jr., “Plane Tool Makers,” and family, in the 1881 U.K. Census. 57 York Street, Lambeth, Surrey.

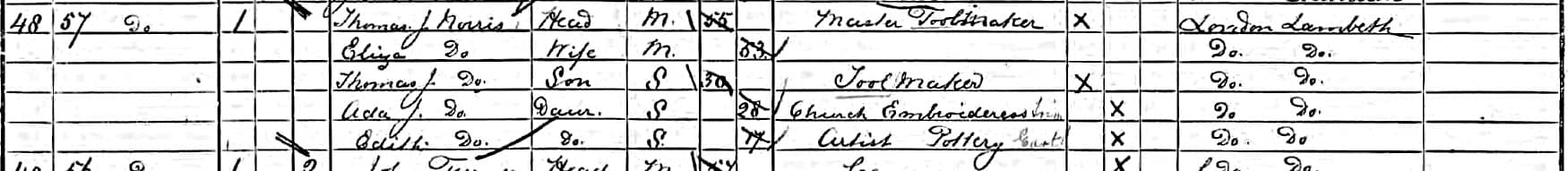

Thomas J.Norris Sr. and Jr., “Master Toolmakers,” and family, in the 1891 U.K. Census. 57 York Street, Lambeth, Surrey.

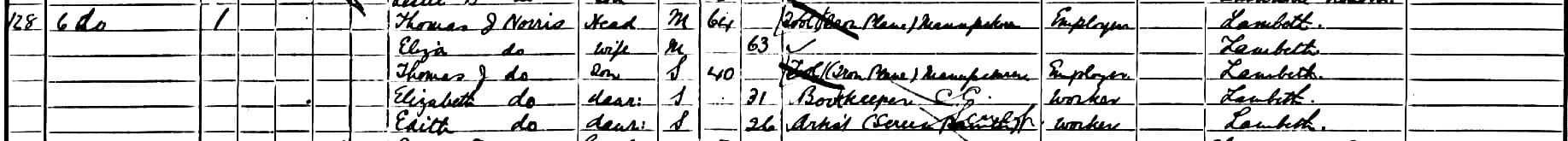

Thomas J.Norris Sr. and Jr., “Tool (Iron Plane) Manufacturers,” and family, in the 1901 U.K. Census. 6 Quarry Road, Wandsworth, Surrey.

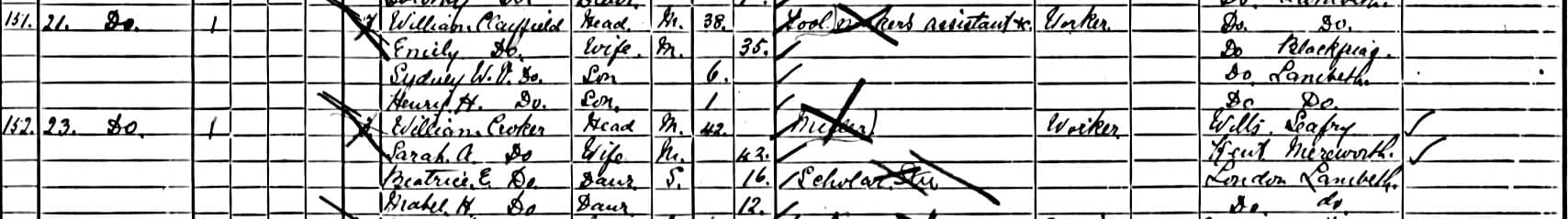

Nos. 21 and 23 York Road, Lambeth in the 1901 U.K. Census, with William Claiffield, “Tool Makers’ Assistant” (salesman) living and working at 21York Road.

Thomas Norris and John Holland

In comparison to Thomas Norris Sr.’s early generalized production, John Holland’s early specialization in metal planemaking was evident from extant early examples of his planes, and in historical documentation. During the 1850s, John Holland lived in the Sheffield area, which was a hotbed of innovation in metallurgy.

Besides George and Joseph Buck, John Holland may also have provided a source of early wholesale work for Thomas Norris Sr., such as finishing off many of Holland’s small plane castings, and making smooth planes to be marked for Holland. Thomas Norris Sr.’s entries in the London Post Office Directories contained a number of omissions over consecutive years which pose a mystery for researchers.

Norris entries at 57 York St. commenced in 1868, although the Norris family was probably at 57 York St. when Eliza Knott Norris was expecting their son Clarence in late 1866. Norris’ listings in the London Directory continue through 1873. From 1874 through 1880, Norris was not listed in the directories; then for 1881 and 1882, Norris was listed again. Furthermore, Norris was absent from the London Directories for 1883 through 1885. And from 1886 forward, Norris was listed consistently in the London City Directories.

Was Thomas Norris Sr. working for John Holland during the years he was not listed in Kelly’s London Post Office Directory? If so, I believe it would have been on a piecework basis rather than a regularly structured employment, with the elder Norris consulting with Holland at his 93 York Street address, and performing most of the actual planemaking work at his own shop at 57 York St. Historically, sole proprietors have been resolutely independent types, which often precluded a formal collaboration.

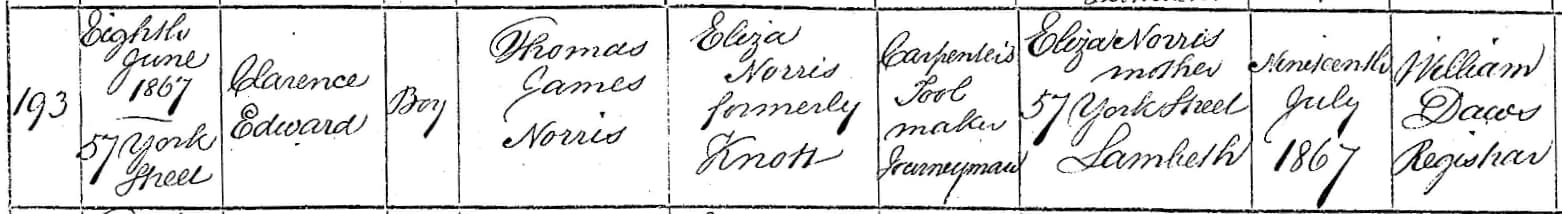

Birth Certificate of Clarence Edward Norris, born 8 June 1867 at 57 York Street, Lambeth, London.

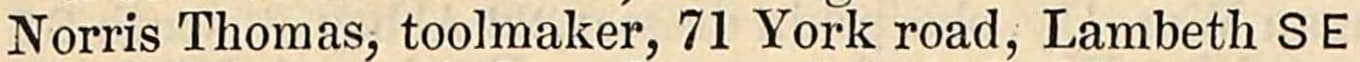

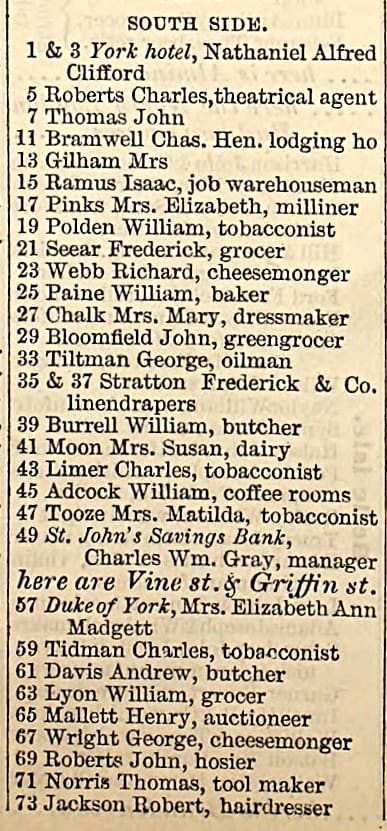

Thomas Norris Toolmaker, 71 York Road. From 1872 London Post Office Directory. The Norris family would have continued to occupy 57 York St. at this time.

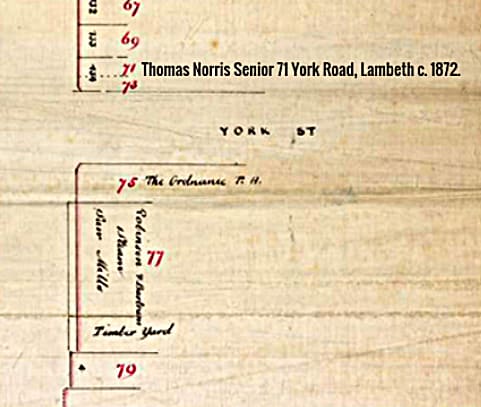

Thomas Norris storefront location at 71 York Road, c. 1871-1872. Detail of York Rd. renumbering plan 1862.

Taking a closer look at Norris’ Directory entries, the year 1872 stood out in particular: this was the first year that John Holland was listed at 93 York Rd. in the London Directory, even though he had been there since late 1870 or early 1871 as his entry in the 1871 U.K. Census showed. More salient was Thomas Norris’ new 1872 entry at 71 York Road: this would have likely been a retail storefront address, as York Road was a busy commercial thoroughfare. Perhaps Holland and Norris came to some agreement regarding a non-compete arrangement, with Holland offering piecework on a wholesale basis to Norris, in return for ending his lease of a retail property selling the same type of merchandise just a a few hundred yards away.

York Road, East side, T. Norris Toolmaker, 71 York Road (1 year only). From London Post Office Directory, 1872.

John Holland, 1st year of entry for 93 York Road, Lambeth. London Post Office Directory, 1872.

John Holland, “Mechanical Tool Maker, Employs Two Men” in the 1881 U. K. census. Now, John Holland declared that he “employed two men” in his entry for the 1881 U.K. Census, and here it is again for another look: one of these men would have been Harry Charles Holland, also a “Mechanical Tool Maker”, and the other would likely be James Henry Holland, who had returned from Sheffield to open a Cutlery and Tool shop at 175 High St. in Deptford.

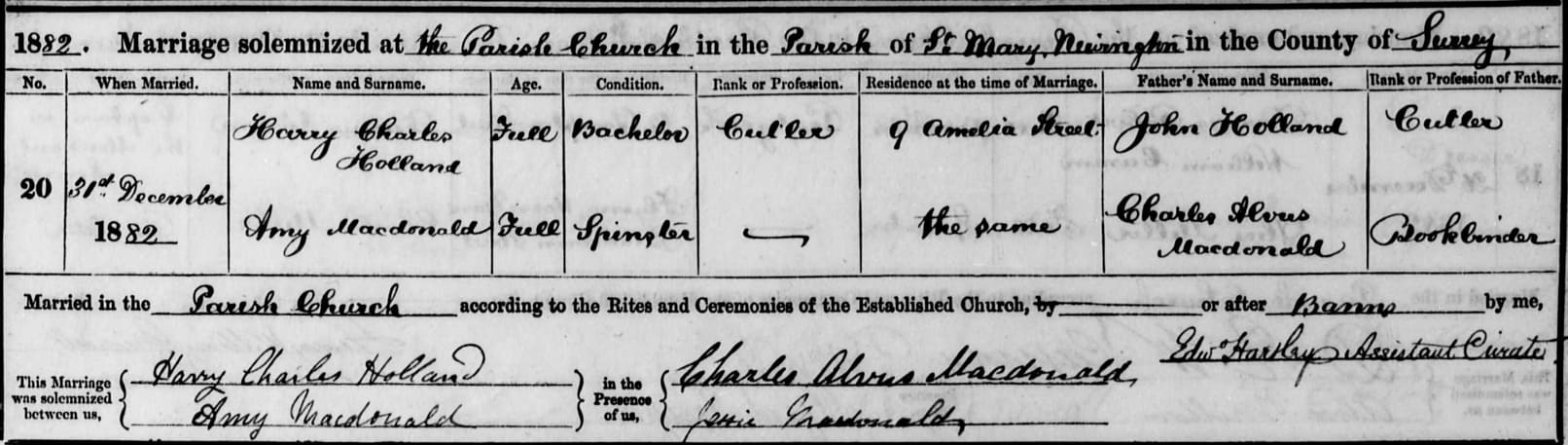

Harry C. Holland married Amy McDonald on 31 December, 1882, living at 9 Amelia St., Southwark, within walking distance. John and Henry were both descibed as “Cutlers,” and Henry was likely still working for his father, John Holland. .

John Holland, in the 1882 London Directory with 93 York Road, and James Henry’s Deptford address. John Holland likely considered his second employee to be James Henry Holland.

Given that father and son both had demanding businesses to run, it is unclear how much time James Henry could actually devote to helping his father with his York Road Planemaking business. Nevertheless John Holland thought enough of this collaboration to include his son’s address in his Commercial Directory listing for 1882. Unfortunately, this was a posthumous listing of James Henry’s location, because he died of typhoid at the age of 28 in 1881.

What about the absence of Thomas Norris in the London Post Office Directories from 1874 through 1880, and 1883 through 1885? Could it be that Thomas Norris Sr. and Junior (after 1882) were continuing to work for Holland out of their own shop at 57 York St. on a piecework basis, along with other ongoing piecework for Joseph and George Buck, Green Pimlico, and others? It was certainly possible, if not likely. But were the omissions for Norris in the London Post Office Directories causally related to the years that Norris senior and junior possibly worked for John Holland?

I contacted a professional genealogist in the U.K., A. Schuyler, who provided some more insight into these omissions for Thomas Norris Senior:

“[The absence of Thomas Norris in the London City Directories] only implies that the building was not surveyed for directories in those years. You will also sometimes find people missing from a census when you know for a fact they lived there. Census enumerators were supposed to return to that house a second time, but they didn’t always do it. Likewise, directory workers could miss a house because they were busy, it was the end of the day, it was lunchtime, or for many other reasons.”

Another look: in 1871, Thomas Norris and his family shared 57 York Street with two other families. 1871 U.K. Census. I checked both the London Post Office Commercial Directory section as well as the Street Guide, or consecutive street numbers section, and found the following for the years in question: for 1874 through 1880, Norris was not listed in either section; for 1883 through 1885, Norris was not listed in either section.

So here we have York Street in 1876 with no. 57 missing. Yet we know from the 1871 U.K. Census that several families occupied 57 York Street at that time. Furthermore, there was almost certainly no fee involved for a basic entry in the Commercial Section of Kelly’s London Post Office Directory during the second half of the 19th century (which might have proved a hindrance to Thomas Norris during lean years). Here is genealogist A. Schuyler again:

“At the beginning, in the 1700s, there was a small fee [for inclusion in the London Directories], but competition among the various publishers soon made that futile, and it was not used by the 1800s.”

York Street Lambeth, consecutive street numbers. No. 57 York Street was not recorded at all (or Norris), as if the building did not exist. London Post Office Directory, 1876.

Harry Charles Holland “Tool Dealer”, his family. along with Samuel Swann Holland, also a “Tool Dealer” 70 Falcon Road, Battersea. 1891 U.K. Census. From 1892, 25 Falcon Road.

After 1890, when John Holland left his shop at 93 York Road, he apparently did not make very many planes after that. There are a few marked for Falcon Road, such as the Holland Thumb/Chariot shown below, but most of the planes that Harry C. Holland sold were finished off Thackeray planes, and a very few Norris planes.

The fact that Thomas Norris Junior became a business partner with his father may indicate that the source of out work for Holland no longer existed as John Holland had effectively retired, closed up shop, and Thomas Norris Senior and Junior had inherited Holland’s business accounts, such as for Mathieson, Holtzapffel, Joseph Buck, and other Tool Dealers.

Holland Thumb/Chariot Plane in German Silver, and marked Falcon Road Battersea.

Kelly’s London P.O. Directory for 1893. Earliest entry found to date with Thomas Jr. listed as partner.

Kelly’s London P.O. Directory for 1899. Earliest entry found to date with 23 York Road listed. Recorded in mid-1898.

Norris & Son added no. 21 York Road in 1899. London Post Office Directory, 1900.

Norris’ 1901 census entry at 6 Quarry Rd.,Wandsworth: “Tool (Iron Plane) Manufacturing.

Norris had moved to Wandsworth in late 1899, but continued to list 57 York St. in the London City Directories as well as renting 23 York Road, which was used in their c. 1900 catalogue. Note that the occupants on York St. were crossed off in 1901, as the buyouts and evictions had occurred recently. Norris was still listed at 57 York St. in the London 1905 P.O. directory as seen above.

Norris & Son 23 York Rd., Lambeth. Photo from Darryl Hutchinson.

Norris’ 1905 P.O. directory entry at 57 York St. with encroaching rail station.

57 York St. in the 1901 U.K. census.

An improvement in means was the reason behind the Norris family leaving 57 York Street, rather than pressure from the railroad. Norris’ sales of fine metal planes were finally paying dividends. Norris employee Charles Henry Payne explained the move. Regarding 57 York Street, Payne revealed that “The Norris family lived in rooms above the works, and another family lived above that. As the family became better off they moved home to Quarry Road Wandsworth, but retained the works in York Street.”

Railroad map, circa 1900-1905, showing proposed area of eminent domain around York St. Map from George Anderson. George found this while researching at the Lambeth Archive, at the Minet Library.

Construction of the Waterloo station began in the 1840s, but it continued on and off throughout the remainder of the 19th century. By the early 1890s, it became clear that the piecemeal approach led to poor planning and that a more unified concept would require a complete rebuild. The only remaining structure from the the original would be the large supporting arches over the marshy soil.

Sketch of York Road in the 1940s with Norris’ rental at 23 delineated. Image from George Anderson, who found it doing research at the Lambeth Archive, Minet Library, in Lambeth.

Thomas rented 23 York Road from as early as 1898 to 1920, when costs from the Great War economy were felt throughout Europe. Thomas Norris Jr. survived the War with some government contracts which granted him access to the metals that he needed. Norris’ 1913 patent for a plane adjustment mechanism, both depth and lateral, solidified his position as the leading high end metal planemaker in the U.K.

Thomas Norris & Son listing at 21 and 23 York Road for 1921. 1921 London Post Office Directory.

R.C. Lampshire, Used Bookseller, 23 York Road; York Tool Supplies, Sydney E. Lyne Tool Dealer, 21 York Road. From 1949 vintage photo.

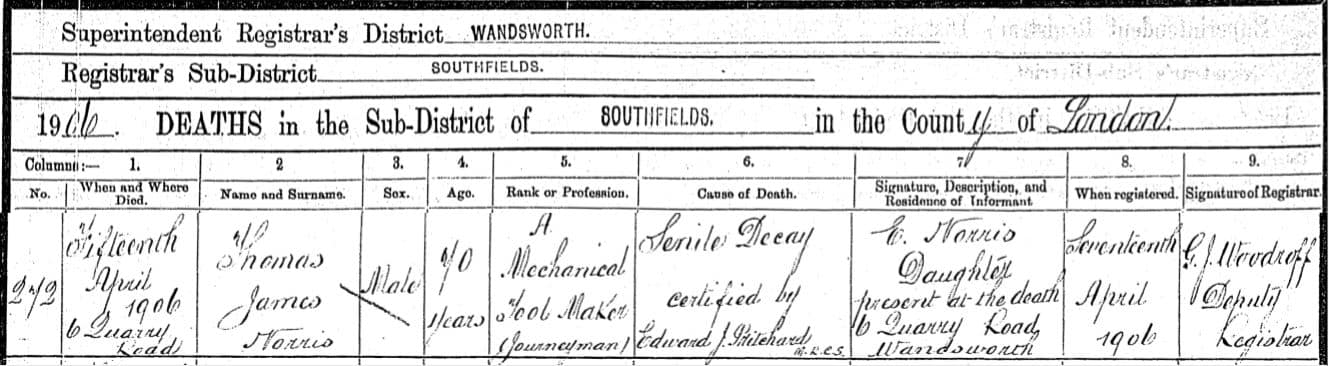

Thomas J. Norris Sr. death certificate, 6 Quarry Rd., Wandsworth, Surrey, 15 April, 1906.

Thomas Norris Sr. in the Probate Calendar.

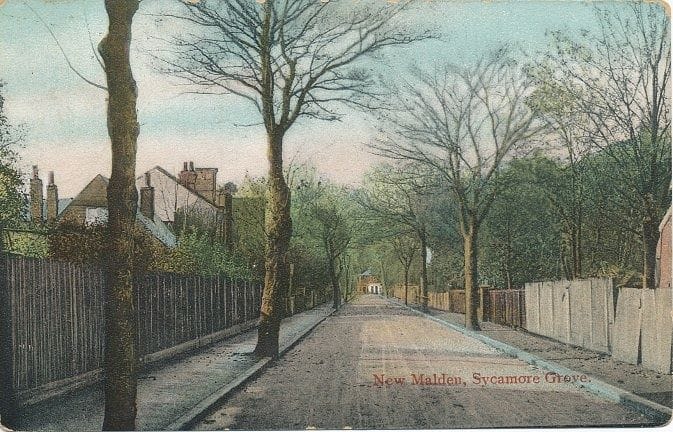

Postcard of Sycamore Grove, New Malden, looking West, circa 1906, when Thomas Norris Jr. moved in. From the collection of George Anderson.

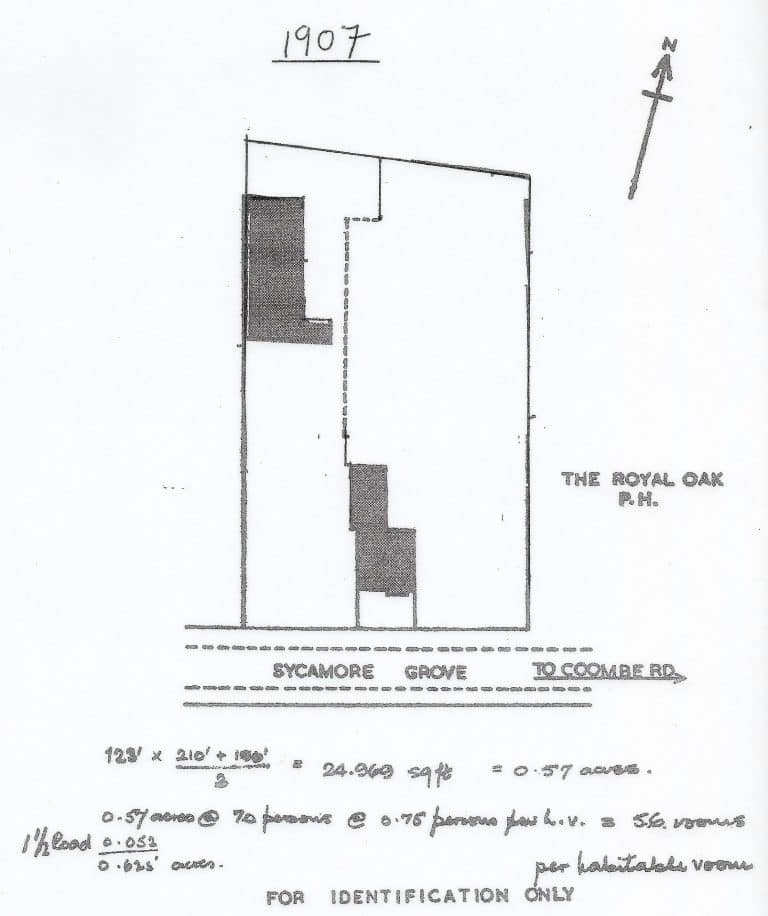

Map with footprint of 3 Sycamore Grove, New Malden, with house and proposed workshop, circa 1907. From collection of George Anderson.

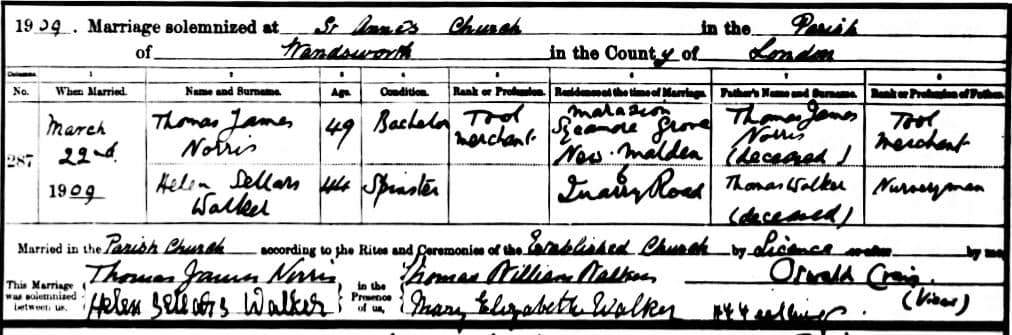

Map with footprint of workshop/factory and house at 3 Sycamore Grove, New Malden, circa 1935. From collection of George Anderson. Thomas Jr., 49, married Helen Sellars Walker, 44. It was a late marriage for both of them. Helen was living at 6 Quarry Rd., Wandsworth, Thomas Sr.’s former house.

Thomas J. Norris married Helen Sellars Walker, 22 March, 1909, at St. Anne’s in Wandsworth.

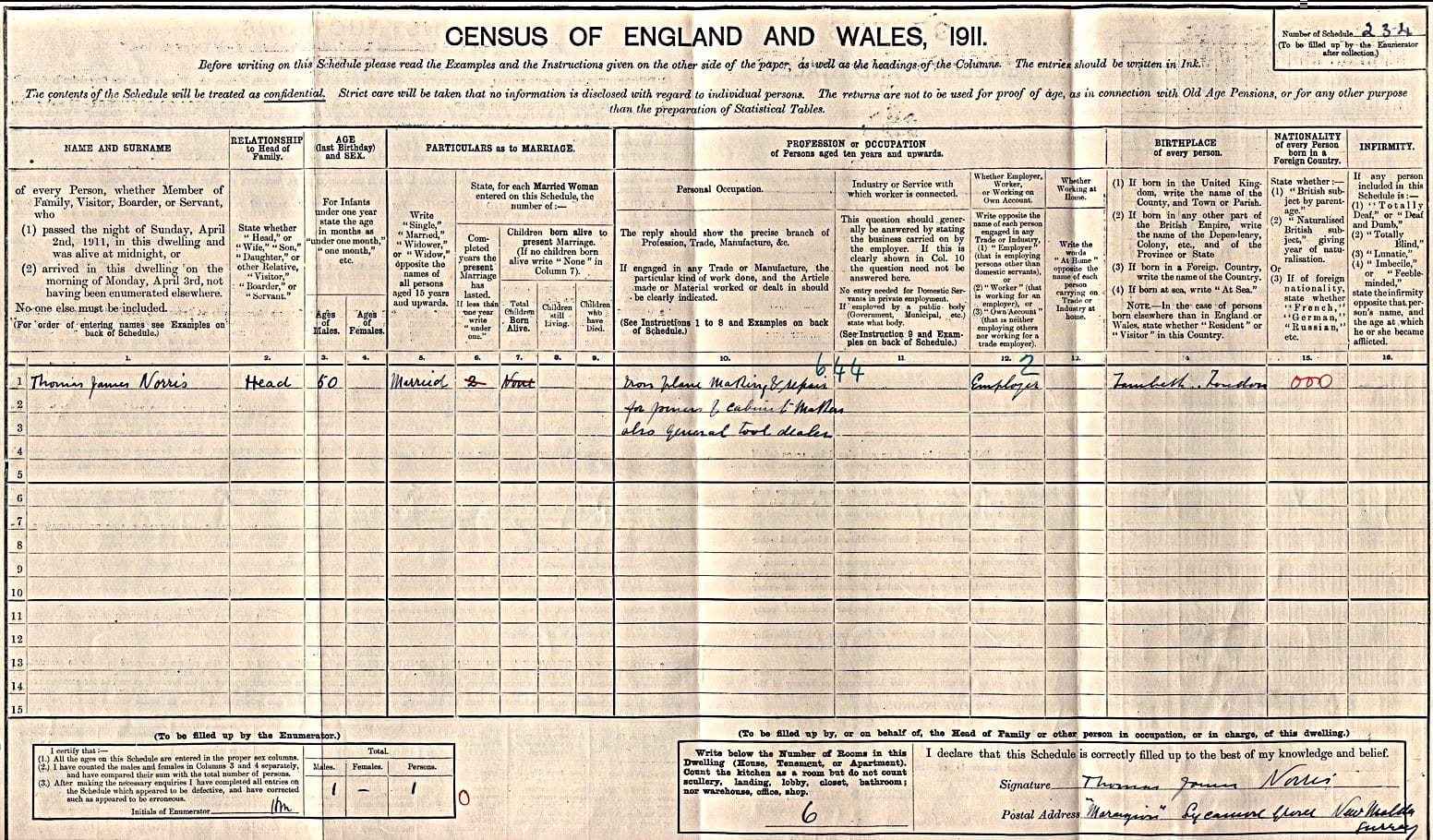

Thomas J. Norris Jr., and family, in the 1911 U.K. Census. Thomas Norris, “Iron plane making and repairs for joiners and cabinet-makers also general tool dealer.” “Marizion,” and Thomas Norris signature.

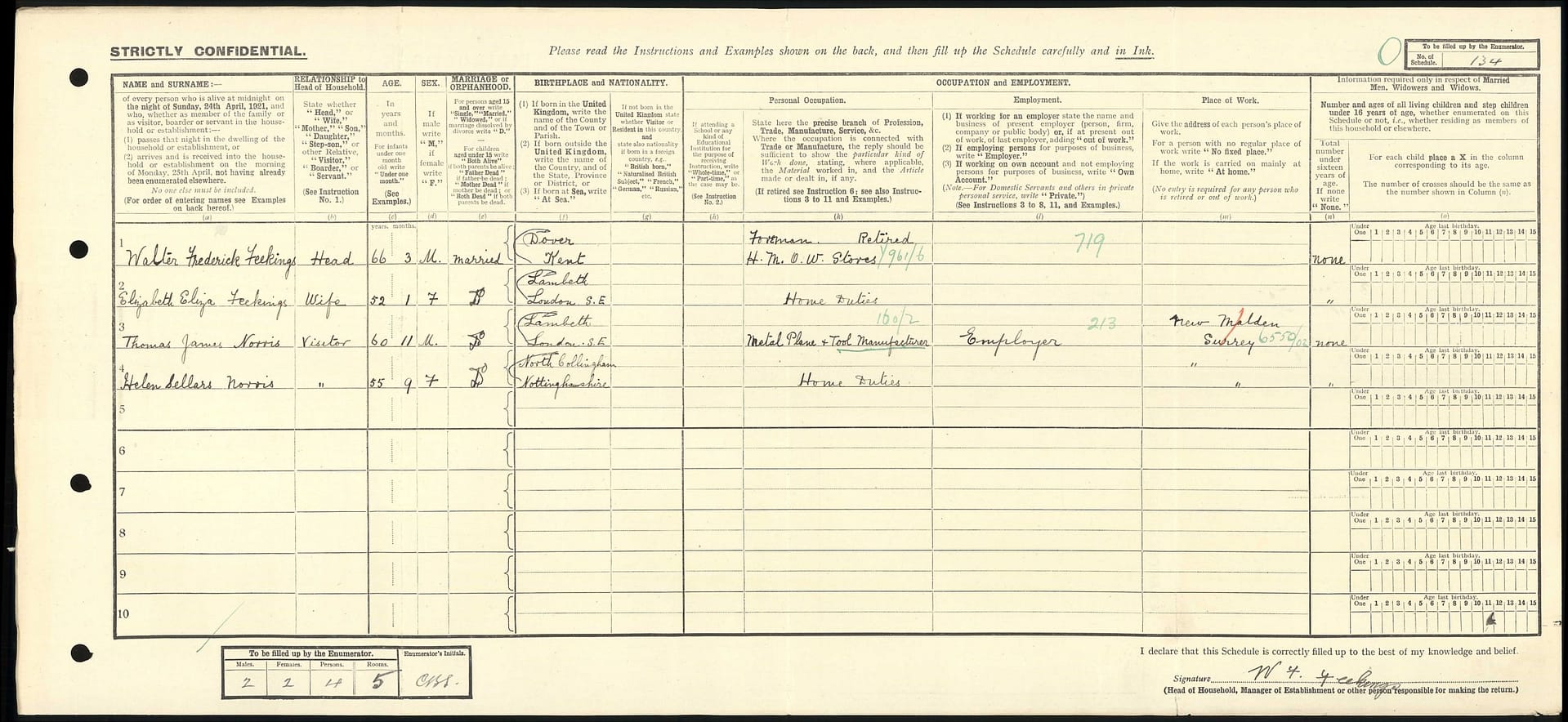

In 1921, Thomas and Helen Norris were visiting Walter and Eliza Feekings (Thomas’ sister) at their residence at Myrtle Cottage, Burshaff on Crouch.

Ordnance Survey Map of New Malden, Surrey County, 1897. Detail of Sycamore Grove. The Royal Oak Pub, at 90 Coombe Road, was Norris’ neighbor on the East side of 3 Sycamore Grove. This map was drawn up about 10 years before Thomas Norris took possession of the property.

Sycamore Grove photo, looking East, towards Coombe Road. Photo from the collection of George Anderson.This photo was taken circa 1900, and was found in the Lambeth Archive, at the Minet Library. A horse drawn wagon was used for delivering goods to the Royal Oak Pub, and you can see the silhouette of a person on the sidewalk. In the left foreground was the sidewalk frontage of “Marizion,” 3 Sycamore Grove, Norris’ home and workshop.

100 years of Buck mitre planes.